Arzawa was a region and political entity in Western Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age. In Hittite texts, the term is used to refer both to a particular kingdom and to a loose confederation of states. The chief Arzawan state, whose capital was at Apasa, is often referred to as Arzawa Minor or Arzawa Proper, while the other Arzawa lands included Mira, Hapalla, Wilusa, and the Seha River Land.

Kingdom of Arzawa 𒅈𒍝𒉿 ar-za-wa | |

|---|---|

| 1700–1300 BC | |

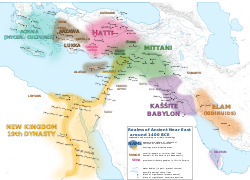

Map of the Arzawa and the surrounding kingdoms, c. 1400 BC. | |

| Capital | Apaša |

| Common languages | Luwian or related languages |

| Government | Monarchy |

| Kings | |

• Late 15th century BC | Kupanta-Kurunta |

• Early 14th century BC | Tarḫuntaradu |

• 1320s BC | Tarkasnawa |

• 1320–1300 BC | Uhha-Ziti |

| Historical era | Bronze Age |

• Established | 1700 BC |

• Disestablished | 1300 BC |

Arzawa is known from contemporary texts documenting its political and military relationships with Egypt and the Hittite Empire. The kingdom had a tumultuous relationship with the Hittites, sometimes allied with them but other times opposing them, in particular in concert with Mycenaean Greece which corresponds to Ahhiyawa of the Hittite sources. During the Amarna Period, Arzawa had achieved sufficient independence that Egypt opened direct diplomatic relations, addressing the Arzawan king Tarhuntaradu as "great king", a title reserved for peers. However, the kingdom was fully subjugated by Mursili II around 1300 BC.

Geography

editThe Kingdom of Arzawa was located in Western Anatolia. Its capital was a coastal city called Apasa, which is believed to have been Ayasuluk Hill at the site of later Ephesus. The hill appears to have been fortified during the Late Bronze Age and contemporary graves suggest that it was a locally important center, though much of the potential ruins are obscured by the later Basilica of St. John.[1][2][3]

In Hittite texts, the term "Arzawa" is also used more broadly to refer to a group of kingdoms including Arzawa itself. Thus, modern-day scholars sometimes use the terms "Arzawa Minor" or "Arzawa Proper" to designate the main kingdom.[4][1] The other "Arzawa Lands" included Mira, Hapalla, Seha, and in later periods Wilusa as well. At times, the Arzawa Lands appear to have banded together as a loose military confederation, which may have been led by the Kingdom of Arzawa itself. However, they were never fully united as a single kingdom, and did not always operate in solidarity with one another.[1]

History

editThe zenith of the kingdom was during the 15th and 14th centuries BC. The Hittites were then weakened, and Arzawa was an ally of Egypt.

Early history

editAround 1650 BC, the Hittite old kingdom ruler Hattusili I raided Arzawan territory. Documents regarding this incident provide the earliest known mention of Arzawa, which in this era was spelled as Arzawiya. Around 1550 BC, the Arzawans joined a broader uprising against the Hittite king Ammuna. However, they were subjugated by Tudhaliya I/II around 1400 BC, concurrently with the Assuwa Revolt.[1]

A Hittite text known as the Indictment of Madduwatta discusses the exploits of an Anatolian warlord named Madduwatta in and around Arzawa during Tudhaliya's reign. The document recounts that Madduwatta launched multiple unsuccessful attacks on Arzawa before seeking a marriage alliance with the Arzawan king Kupanta-Kurunta.[5] Maduwatta then allied with a certain Attarsiya, the man of Ahhiyawa; the latter country being widely accepted as Mycenaean Greece or part of it.[6] In general during the period 1400-1190 BC Hittite records mention that the populations of Arzawa and Ahhiyawa were in close contact.[7]

Zenith

editAround 1370 BC, during the reign of Tudhaliya III, Arzawa conquered a large portion of Western Anatolia. Their army swept across the Lower Land, into territories that the Hittites had never lost before, reaching as far as the border as the Hittite homeland.[1][8]

In response, the Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep III opened diplomatic relations with the Arzawan king Tarhundaradu, proposing a marriage alliance. In his letter, the pharaoh refers to the Hittite Empire as paralyzed, suggesting that he expected Arzawa to replace it as the major regional power. This correspondence had to be carried out in Hittite, since the Arzawan court did not have scribes capable of writing Akkadian, the contemporary lingua franca for international diplomacy.[9][1][8]

Arzawa never achieved political or military supremacy over Anatolia. The territory they had seized was soon recaptured by the Hittite prince Šuppiluliuma I. After coming to the throne around 1350 BC, Šuppiluliuma continued to campaign against Arzawa, even installing pro-Hittite rulers in former Arzawan vassal states such as Mira.[1][8]

Revolt and fragmentation

editThe Arzawa lands were fully subjugated by the Hittites around 1300 BC, after an unsuccessful rebellion. When Mursili II ascended to the Hittite throne, much of Anatolia erupted into rebellion. At this time, Uhha-Ziti ruled Arzawa Minor, the epicenter of the broader Arzawa confederation. Uhha-Ziti provoked the new Hittite king by providing sanctuary to anti-Hittite rebels and refusing to extradite them. In doing so, he was supported by Manapa-Tarhunta of the Arzawan Seha River Land as well as by the king of Ahhiyawa. However, he was also opposed by King Mashuiluwa of Mira, one of the other Arzawan kingdoms.[10][11][12]

The Hittites responded with full military force. The Annals of Mursili claim that Uhha-Ziti was incapacitated after being struck by lightning and that his capital city of Apasa fell after a short siege. Uhha-Ziti and his family fled to Ahhiyawa (Mycenaean)-controlled islands in the Aegean, while local populations faced further sieges and deportations. Uhha-Zitti died shortly afterwards in exile, and his son Tapalazunawali failed to regain control of the kingdom.[10][11] As for the deportees around 6,200 of them comprised the royal share who ended up serving the Hittite king.[13]

In the aftermath of the Arzawa defeat the nearby settlement of Miletus (Millawanda in Hittite records) was affected and probably burnt by the Hittites due to previous Mycenaean involvement in support of the Arzawan side. Nevertheless Mycenaeans retained control of Miletus.[14]

Hittite records also mention Piyama-Radu a local warlord who was active in Arzawa and fled to Mycenaean controlled territory that time. [15] It is not clear if the Arzawan pockets of resistance were overcome by Hittite forces.[16]

Society

editThe Arzawa Lands were unusual in Western Anatolia for having a state-level society, being ruled by kings who conducted formal relations with one another and with foreign powers. By contrast, other nearby groups such as the Lukka, Karkiya, and Masa, were stateless societies ruled by councils of elders, and thus had more informal relations with outsiders.[1]

The languages spoken in Arzawa cannot be directly determined due to the paucity of written sources. The primary languages are believed to have been from the Anatolian family, and in particular from the Luwic subgroup. Some scholars such as Ilya Yakubovich argue that Arzawa was predominantly inhabited by speakers of Proto-Lydian and Proto-Carian. Others such as Trevor Bryce regard it as Luwian-speaking.[1][17]

In its final century of independence, Arzawan culture was influenced by the culture of Mycenaean Greece, which was beginning to expand into Western Anatolia. For instance, Mycenaean-style pottery and architecture are both evidenced at Apasa, which may have even had a Mycenaean cult center at the site of the later Temple of Artemis.[18]

Amarna letters

editThe Amarna letters include a pair of letters between the Arzawan ruler Tarhundaradu and the Egyptian Pharaoh Amenhotep III. One letter, known to modern scholars as EA 31, was sent from the pharaoh to Arzawa; the other, known as EA 32, contains the Arzawan king's reply. While most of the Amarna letters were written in the Akkadian language, these letters were written in Hittite. The Egyptian letter EA 31 was written by a scribe not fully proficient in Hittite, and contains significant grammatical errors.[19]

When these letters were excavated in the 1880s, they were the first Hittite texts to be discovered. Because they were written in the already-deciphered Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform script, scholars were able to pronounce the words, and could often make inferences about their meanings based on the letters' formulaic rhetorical style and use of sumerograms. Based on these inferences, the scholar Jorgen A. Knudtzon proposed that the language was from the Indo-European family. This hypothesis proved correct after thousands more tablets were discovered at Hattusa.[19]

The letters have also proved relevant in debates about Arzawan geography. While the general consensus suggests that Arzawa's capital was at Ephesos, chemical analyses suggest that EA 32 was written on clay from far to the north, near Kyme in the region later known as the Aeolis.[20][21]

Kings of Arzawa

edit- Kupanta-Kurunta c.1440s BC

- Tarhundaradu c.1370s BC

- Tarkasnawa, king of Mira, c.1320s BC

- Uhha-Ziti - last ruler c. 1320-1300 BC

See also

editNotes

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i Bryce, Trevor (2011). "The Late Bronze Age in the West and the Aegean". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0015.

- ^ Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 46. ISBN 978-1589832688.

- ^ Günel, Sevinç (2017). "The West: Archaeology". In Weeden, Mark; Ullmann, Lee (eds.). Hittite Landscape and Geography. Brill. pp. 119–133. doi:10.1163/9789004349391_014. ISBN 978-90-04-34939-1.

- ^ Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-1589832688.

- ^ Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. p. 98. ISBN 978-1589832688.

- ^ Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric, 2012: 69, 99

- ^ Kelder, 2003–2004: 66

- ^ a b c Beal, Richard (2011). "Hittite Anatolia: A Political History". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press. p. 594. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0026.

- ^ Hoffner, Harry (2009). Letters from the Hittite Kingdom. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 269–275. ISBN 978-1589832121.

- ^ a b Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Society of Biblical Literature. pp. 45–47. ISBN 978-1589832688.

- ^ a b Bryce, T. (2005). The Trojans and their Neighbours. Taylor & Francis. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-415-34959-8.

- ^ Kelder, Jorrit (2004–2005). "Mycenaeans in Western Anatolia" (PDF). Talanta: Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. XXXVI–XXXVII: 66.

- ^ Strauss, Barry (21 August 2007). The Trojan War: A New History. Simon and Schuster. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7432-6442-6.

- ^ Kelder, 2003–2004: 66-67

- ^ Matthews, Roger; Roemer, Cornelia (16 September 2016). Ancient Perspectives on Egypt. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-315-43491-9.

- ^ Kelder, 2003–2004: 67

- ^ Yakubovich 2010, pp. 107-11

- ^ Kelder, Jorrit (2004–2005). "Mycenaeans in Western Anatolia" (PDF). Talanta: Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. XXXVI–XXXVII: 59,66.

- ^ a b Beckman, Gary (2011). "The Hittite Language". In Steadman, Sharon; McMahon, Gregory (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Anatolia. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195376142.013.0022. hdl:2027.42/86652.

- ^ Max Gander (2014), An Alternative View on the Location of Arzawa. Hittitology today: Studies on Hittite and Neo-Hittite Anatolia in Honor of Emmanuel Laroche’s 100th Birthday. Alice Mouton, ed. p. 163-190

- ^ Kerschner, M., “On the Provenance of Aiolian Pottery”, in: Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt. Studies on East Greek Pottery and Exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean (The British Museum Research Publication 162), Villing, A. / Schlotzhauer, U. (éds.). British Museum Company, Londres, 2006, 109-126. p.115

External links

edit