The Dunedin (1874–90) was the first ship to successfully transport a full cargo of refrigerated meat from New Zealand to England. In this capacity, it provided the impetus to develop the capacity of New Zealand as a major provider of agricultural exports, notwithstanding its remoteness from most markets. Dunedin disappeared at sea in 1890.

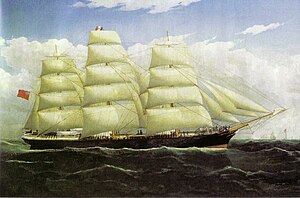

The Dunedin in 1876, wearing the colours of Shaw, Savill & Albion Line of London (retained in 1882). Painting by Frederick Tudgay (1841–1921), 47 cm by 77 cm oil on canvas, originally owned by the ship's captain, John Whitson.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dunedin |

| Namesake | Dunedin, New Zealand |

| Owner | Albion Line |

| Operator | P Henderson & Company |

| Builder | Robert Duncan and Co., Port Glasgow |

| Cost | £23,750 pounds |

| Yard number | 67085 |

| Launched | 3 March 1874 |

| Maiden voyage | Lyttelton |

| Fate | Last sighted 19 March 1890, near New Zealand |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Auckland class |

| Type | Full-rigged ship |

| Tonnage | 1320 gross, 1130 net[1] |

| Length | 241.05 ft (73.47 m) |

| Beam | 36.1 ft (11.0 m) |

| Depth | 20.9 ft (6.4 m) |

| Decks | 2 |

| Sail plan | Three-masted full-rigged ship |

| Crew | 29-34 |

| Notes | Iron-hulled sailing ship Clipper ship |

Ship origins

editRobert Duncan and Co built the 1,320 gross register ton, 241.05 ft (73.47 m) Dunedin at Port Glasgow in Scotland in 1874 for the Albion Line (later the Shaw, Savill & Albion Line). Her ship number was 67085, and she cost £23,750 pound sterling, equivalent to £2,790,000 in 2023. She was one of six Auckland class emigrant vessels, each designed to carry 400 passengers. In 1881, still painted in her original colours of a black hull with a gold band and pink boot topping as shown, she was refitted by William Soltau Davidson with a Bell Coleman refrigeration machine. She took the first load of frozen meat from New Zealand to the United Kingdom in 1882.

Immigrant ship

editHer first trip to New Zealand was in 1874 under Captain Whitson, who sailed her from London to Lyttelton, New Zealand in 98 days. In 1875, he sailed from London to Auckland in 94 days. All seven of her voyages from London to New Zealand prior to conversion were completed in under 100 days. Only one voyage (in 1876) required quarantine at Otago. Whitson remained her captain throughout the period she sailed with immigrants. In 1886, five years after she had been converted to take refrigerated cargo, Captain Arthur F Roberts became her captain after Captain Whitson had died at Oamaru on 4 May that year.[2] Roberts, a Master Mariner, had been captain of the White Eagle and Trevelyn. Both these ships had sailed to New Zealand under his command. Even after her conversion, the Dunedin continued to carry passengers.[3]

Background to the frozen meat shipment

editEnglish demand

editThis historical importance of the Dunedin is due to this meat shipment, which proved refrigerated meat could be exported long distances, so establishing the New Zealand meat export industry, and transforming agriculture in New Zealand and Australia. In the United Kingdom (UK), the rapidly expanding population had outrun the supply of local meat, resulting in rapid increases in prices. However, the shipment of livestock from New Zealand to England was prohibitively expensive. New Zealand did export some canned meat, but the industry was in its infancy, and while the product was popular in the Pacific islands, it was less so in England.

Early attempts

editThe first attempt to ship refrigerated meat from Australasia was made when the Northam sailed from Australia to England in 1876; however the refrigeration machinery broke down en route and so the cargo was lost. Later that year chilled beef was sent from the United States to England (a shorter journey, at cooler, higher latitudes) and, although spoilage was high, this voyage provided some encouragement to Australian and New Zealand promoters of refrigeration. During 1877 the steamers Le Frigorifique and Paraguay carried frozen mutton from Argentina to France, proving the concept, if not the economic case, for longer-distance refrigerated shipping. In 1879 the Strathleven, equipped with compression refrigeration, sailed from Sydney with 40 long tons (41 t) of frozen beef and mutton as a small part of her cargo, and this meat arrived in good condition. As a result of this success a Director of the New Zealand and Australian Land Company (NZALC), William Soltau Davidson, sent an employee, Thomas Brydone, from New Zealand to the UK to investigate compression refrigeration units.

The Dunedin refit

editIn 1880 Davidson convinced the company to invest in refrigeration. Teaming up with James Galbraith of the Albion shipping company, they approached John Bell and Sons and Joseph James Coleman, who had been involved in American chilled beef shipments. As a result of negotiations, Albion agreed to refit the Dunedin with a Bell-Coleman compression refrigeration machine, cooling the entire hold. Using 3 tons of coal a day, this steam-powered machine could chill the hold to 22 °C (40 °F) below surrounding air temperature, freezing the cargo in the temperate climate of southern New Zealand, and then maintaining it beneath zero through the tropics. The Dunedin was refitted in May 1881, the most visible sign being a funnel for the refrigeration plant between her fore and main masts – sometimes leading her to be mistaken for a steamship. The refitted Dunedin arrived in Dunedin's Port Chalmers at the end of November 1881.

1882 voyage

editFrom 5 December 1881, a herd of 10,000 Merino/Lincoln and Leicester crossbreed sheep on NZALC's Totara Estate near Oamaru was slaughtered at a purpose-built slaughter works close to the railhead there. The carcasses were sent overnight by goods trains with a central block of ice to be loaded on the Dunedin, where they were sewn into calico bags and frozen. To prove the process, the first frozen carcasses were taken off the ship, thawed and cut.

After 7 days of loading, the crankshaft of the compressor broke, damaging the machine's casing and causing the loss of the 643 sheep carcasses stowed. It took a month for a local machinist to rebuild the crankshaft and associated machinery. The frozen carcasses were resold locally during this time, and, encouragingly, they were considered to be indistinguishable from fresh meat. On 15 February 1882, the Dunedin sailed with 4331 mutton, 598 lamb and 22 pig carcasses, 250 kegs of butter, hare, pheasant, turkey, chicken and 2226 sheep tongues. Sparks from the compressor's boiler created a fire hazard. When the vessel became becalmed in the tropics, crew noticed that the cold air in the hold was not circulating properly. To save his historic cargo, Captain John Whitson crawled inside and sawed extra air holes, almost freezing to death in the process. Crew members managed to pull him out by a rope and resuscitated him.[4]

The Dunedin arrived in London 98 days after setting sail. Carcasses were sold at the Smithfield market over two weeks by John Swan and Sons, who noted butchers' concerns about the quality of meat from the experimental transport; "Directly the meat was placed on the market, its superiority over the Australian [frozen] meat struck us, and in fact the entire trade". Although crossed with the primarily wool bearing Merino, the well fed New Zealand sheep weighed an average of over 40 kilograms (88 lb), and some exceeded 90 kilograms (200 lb). Only one carcass was condemned.[5] The Times commented "Today we have to record such a triumph over physical difficulties, as would have been incredible, even unimaginable, a very few days ago...". After meeting all costs, NZALC's profit from the voyage was £4700.

Outcome

editThe shipment effectively began the refrigerated meat industry and assured New Zealand's early dominance in it. The Marlborough—sister ship to the Dunedin – was immediately converted and joined the trade the next year, along with the rival New Zealand Shipping Company vessel Mataura, while the German steamer Marsala began carrying frozen New Zealand lamb in December 1882. Within five years, 172 shipments of frozen meat were sent from New Zealand to the United Kingdom, of which only 9 had significant amounts of meat condemned. The Dunedin completed nine more voyages until its loss in 1890.[6]

Disappearance

editHer sister ship, the Marlborough had sailed in January 1890 and the Dunedin followed in March, sailing from Oamaru on 19 March with 34 crew including Captain Roberts.[7] Roberts' daughter was the only passenger. By July concerns were being expressed about the ship, as she normally made the journey in 90 or so days and by October she was noted as missing.[8][9]

Although both the Dunedin and Marlborough were sighted in the Southern Ocean after leaving New Zealand, neither was seen again after that.[10] No trace was found of the Dunedin and it was presumed both she and the Marlborough hit icebergs in the Southern Ocean. RMS Rimutaka had reported that there were great quantities of ice in the Southern Ocean on their normal route between the Chatham Islands and Cape Horn when she sailed through the area in early to mid February.[11] The Board of Enquiry concluded that apart from hitting an iceberg another possibility was that the Dunedin had come to grief in a storm. They found that the ship was seaworthy, appropriately laden, and sailed by an experienced Captain and crew.[12]

There were two reports of sightings of the Dunedin in 1890; one by the ship London which said they had sailed near each other in the vicinity of Cape Horn prior to being separated in a storm, and another about her being found on the coast of Brazil with yellow fever on board. This latter story was dismissed as untrue.[13]

See also

editReferences

editNotes

edit- ^ "First Entry Report for Iron Ship Dunedin, 23 March 1874". Lloyd's Register Foundation. Lloyd's Register Group.

- ^ "Passing Notes". Otago Witness. No. 1798. 7 May 1886. p. 18. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ "Shipping: Romance on the high seas". Otago Daily Times. No. 7781. 27 January 1887. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ "First frozen meat shipment leaves New Zealand". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture and Heritage.

- ^ Williscroft, Colin, ed. (2007). A Lasting Legacy: A 125 Year History of New Zealand Farming since the first Frozen Meat Shipment. Auckland: New Zealand Rural Press. OCLC 174069450.

- ^ "The Dunedin | NZETC". nzetc.victoria.ac.nz. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ "Shipping – Port of Oamaru". North Otago Times. Vol. XXXIV, no. 6994. 19 March 1890. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ "An Overdue New Zealand Trader". Dundee Courier. 14 July 1890. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Last Week's Wrecks". Nottingham Evening Post. 24 October 1890. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Druett, Joan (1983). "The Dunedin". Exotic Intruders: The Introduction of Plants and Animals into New Zealand. Auckland: Heinemann. ISBN 9780868633978. OCLC 10841761.

- ^ "[Untitled notices]". The Auckland Evening Star. Vol. XXI, no. 138. 12 June 1890. p. 5. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ "The Missing Ship Dunedin". Oamaru Mail. Vol. XVI, no. 4865. 6 January 1891. p. 2. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

- ^ "The missing ship Dunedin". The Press. Vol. XLVIII, no. 7752. 5 January 1891. p. 3. Retrieved 1 January 2019 – via Papers Past, National Library of New Zealand.

Sources

edit- Williscroft, Colin, ed. (2007). A Lasting Legacy: A 125 Year History of New Zealand Farming since the first Frozen Meat Shipment. Auckland: New Zealand Rural Press. OCLC 174069450.

- Palmer, Mervyn (1993). "Davidson, William Soltau". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- McLintock, Alexander Hare, ed. (1966). "Ships, Famous: Dunedin". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Vol. III. p. 250. OCLC 1137411. Retrieved 2 January 2019 – via Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- Laird, Dorothy (1961). Paddy Henderson. Glasgow: George Outram and Company Limited.