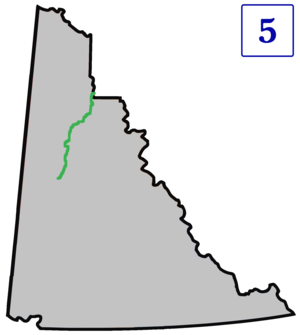

The Dempster Highway, also referred to as Yukon Highway 5 and Northwest Territories Highway 8, is a highway in Canada that connects the Klondike Highway in Yukon to Inuvik, Northwest Territories on the Mackenzie River delta. The highway crosses the Peel and the Mackenzie rivers using a combination of seasonal ferry services and ice bridges. Year-round road access from Inuvik to Tuktoyaktuk opened in November 2017, with the completion of the Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway,[1] creating the first all-weather road route connecting the Canadian road network with the Arctic Ocean.

| Yukon Highway 5 Northwest Territories Highway 8 | ||||

| ||||

| Route information | ||||

| Maintained by Department of Highways and Public Works | ||||

| Length | 737.5 km (458.3 mi) YT-5: 465 km (289 mi) NWT-8: 271 km (168 mi) | |||

| Major junctions | ||||

| South end | ||||

| North end | ||||

| Location | ||||

| Country | Canada | |||

| Province | Yukon | |||

| Highway system | ||||

|

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

The highway is named for North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) officer William Dempster, who earned renown for discovering the fate of a lost NWMP patrol in 1911.

Route description

editThe highway begins 40 km (25 mi) east of Dawson City, Yukon on the Klondike Highway. There are no highway or major road intersections along the highway's route. It extends 736 km (457 mi) in a north-northeasterly direction to Inuvik, Northwest Territories, passing through Tombstone Territorial Park and crossing the Ogilvie and Richardson mountain ranges.

History

editThe Dempster Highway roughly follows the old dog sled route from Dawson City to Fort McPherson and is named for Corporal (later Inspector) William Dempster of the North-West Mounted Police.[2]

During the late 19th century, and in response to the Klondike Gold Rush, the North-West Mounted Police established a presence in the Yukon and Northwest Territories. Their activities included winter dog sled patrols between outposts and communities. One such patrol followed a route from Dawson City to the NWMP outpost at Fort McPherson, established in 1903.

In December 1910, NWMP Inspector Francis Joseph Fitzgerald led three men on the annual winter patrol from Fort McPherson to Dawson City. They became lost on the trail, and subsequently died of exposure and starvation. When they failed to arrive in Dawson City as expected, Corporal Dempster and two constables were sent out on a rescue patrol in March 1911. Dempster and his men found the bodies of Fitzgerald's patrol on March 22, 1911.[3]

Construction

editIn 1958, as oil and gas exploration were expanding in the Mackenzie Delta, the Canadian government decided to build a road from Dawson City in Yukon to Aklavik in the Northwest Territories. The road was intended as an overland, year-round supply link to southern Canada.[4] Survey work began in 1958.[5]

With the August, 1959, discovery of oil in the Eagle Plains area, the government granted concessions to the oil industry to stimulate more exploration in the area. This provided more motivation for a road to transport equipment, infrastructure, and revenue to and from the sites.[4] Construction of the road, then known as Yukon Territorial Road No. 11, began at Dawson City in January 1959.[6] The northern terminus of the road was changed to the new town of Inuvik. Due to high costs and ongoing funding disagreements between the federal and Yukon governments, progress was slow until 1961. Once the Eagle Plains oil discovery was found to have no commercial potential, construction stopped in 1962 after 115 km (71 mi) of roadbed had been built.[4]

Seasonal maintenance of the existing road continued but no further work was done. In 1964, the road was renamed the Dempster Highway, after petitions by Vancouver Yukoners Association and the Yukon Order of Pioneers.[5] Construction resumed in 1970 as the Canadian government sought to assert sovereignty over their Arctic territories after the American discovery of oil and gas deposits at Prudhoe Bay, Alaska in 1968. Work was further motivated by speculation that an oil pipeline might be built in the Mackenzie Valley.

At the time of its construction, the highway was the most northerly major road project to date. Weather and daylight conditions presented challenges. In 1979, a work crew was trapped in a blizzard in the Richardson Mountains and was almost lost.[5] Construction had to account for the permafrost; heat transfer from the highway to the ground had to be prevented so the permafrost would not melt. To address this, the road was built on top of a gravel berm, ranging from 1.2 to 2.4 m (3 ft 11 in to 7 ft 10 in), to insulate the permafrost from the road above.[4] Some construction was completed by the Canadian Forces; 3 Field Squadron, RCE from CFB Chilliwack built bridges over the Ogilvie River in 1971[7] and the Eagle River in 1977.[8]

The final section of road was completed in 1978, at a cost of $132 million.[5] The highway was officially opened on August 18, 1979, at Flat Creek, Yukon.[6]

Gallery

edit-

Dempster Highway south of Inuvik

-

Sign on Dempster Highway

-

Arctic spruce

-

Dempster Highway

-

Mt. Tombstone in Tombstone Territorial Park

-

The Eagle Plains Hotel, the only lodging establishment along the Dempster Highway, in July 2022

-

Sign in Eagle Plains: "High winds and blowing snow"

-

Midnight sun over the Dempster near Inuvik

-

The Dempster Highway approaching the MacKenzie River ferry crossing, from the south, with buildings of Tsiigehtchic visible to the right

-

Pavilion marking where the Dempster Highway crosses the Arctic Circle

Major intersections

edit| Territory | Region | Location | km[9] | mi | Destinations | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yukon | unorganized | | 0 | 0.0 | Hwy 2 (Klondike Highway) – Dawson City, Whitehorse | |

| 82 | 51 | North Fork Pass – 1,289 m (4,229 ft) | Highest point on the Dempster Highway | |||

| Eagle Plains | 369 | 229 | First available services | |||

| | 391 | 243 | Wiley Aerodrome | Uses a portion of the highway as its runway. | ||

| 405 | 252 | Arctic Circle | ||||

| Yukon – Northwest Territories border | 465 | 289 | Hwy 5 northern terminus • Highway 8 southern terminus One hour time change (summer only) | |||

| Northwest Territories | Inuvik | | 539 | 335 | Crosses the Peel River MV Abraham Francis (June to October) • Ice bridge (late November to April)[10] | |

| Fort McPherson | 550 | 340 | Second and last available services | |||

| Tsiigehtchic | 608 | 378 | Crosses the Mackenzie River MV Louis Cardinal (June to October) • Ice bridge (late November to April)[10] | |||

| Inuvik | 736 | 457 | Highway 10 north (Inuvik–Tuktoyaktuk Highway) – Tuktoyaktuk | |||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| ||||||

See also

edit- List of Yukon territorial highways

- Dalton Highway – the only other all-season highway to cross the Arctic Circle in North America

References

edit- ^ "GCR - News - First ever road to Canada's Arctic coast to open this week". www.globalconstructionreview.com. Retrieved 2017-11-23.

- ^ Morrison, William R. (January 1986). "W.J.D. Dempster". Arctic. 39 (2): 190–191. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ North, Dick (2004). The Lost Patrol: The Mounties' Yukon Tragedy. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-59228-573-2.

- ^ a b c d "Dempster Highway History". Yukon Info. PR Services Ltd. Retrieved 26 November 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d Gates, Michael (4 March 2015). "Building the Dempster Highway: an engineering challenge". Yukon News. Yukon News and Black Press Group Ltd. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Dempster Highway". Yukon Info. PR Services Ltd. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Gray, Don (5 January 2014). "An Engineering Memoir: A Bridge in the Yukon 1971". e-Veritas. Royal Military College Club of Canada. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "Colonel Commandant, BGen S.M. Irwin, CD (Ret'd)". The Canadian Military Engineers Association. Canadian Military Engineers Association. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ "The Route". The Dempster Highway. Spectacular Northwest Territories. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Ferries". Government of Northwest Territories. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

External links

edit- Opening of the Dempster Highway

- Map of the highway Archived 2012-04-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Dempster Highway at Inuvik Town website

- Dempster Highway at Travel Yukon

- Dempster Highway road trip article on the Economist's More Intelligent Life website

- Detailed Dempster Highway article by Dallas Morning News travel writer Dave Levinthal

- Video of winter crossing at Tsiigehtchic