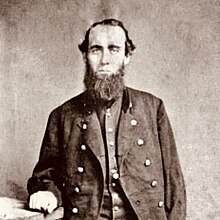

Daniel Stover (November 26, 1826 – December 18, 1864) was an American farmer in Tennessee. He was a son-in-law of Andrew Johnson (who became president of the United States in 1865). Stover was one of the leaders of the East Tennessee bridge burnings, a guerrilla warfare action of the American Civil War that was intended to clear the way for federal occupation of the region, which generally opposed secession. He died of illness in 1864.

Biography

editBorn in Carter County, Tennessee, Stover married Andrew Johnson's younger daughter Mary Johnson in 1852. Stover had a "fine plantation" in the Watauga Valley.[1] In 1860, on the cusp of the Civil War, the family was living together in Carter County. Daniel Stover owned a farm worth US$18,000 (equivalent to $610,400 in 2023) and a personal estate worth US$12,000 (equivalent to $406,933 in 2023). The couple had three children: Lillie, Sarah, and Andrew Johnson Stover.[2]

During the first autumn of the American Civil War, Stover participated in a guerrilla warfare action called the East Tennessee bridge burnings. He was one of four men who knew of the plan prior to the last 24 hours before the attacks were to be executed.[3] The November 8, 1861 bridge burning was carried out with the approval of Union leaders, including Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson, and was supposed to clear the way for the occupation of East Tennessee by federal forces. Nine bridges were targeted, five were destroyed; Stover led the raid that successfully destroyed Holston River Bridge at Union Depot, also called Zollicoffer, now called Bluff City, Tennessee.[4]

Col. Stover having selected about thirty men from among the citizens, the most prudent reliable men that could be found in the vicinity of Elizabethton, and swore them into the military service at Reuben Miller's barn at the head of Indian Creek, for that purpose. These men coming from different directions met near Elizabethton and the nature of the enterprise was explained to them by Col. Stover, and they were informed by him that in addition to the honor attached to doing so great a service for the country they were to be paid by the Federal Government. He explained to them also that Gen. Thomas with his army was then, as he believed, on the borders of East Tennessee, and immediately upon the burning of the bridges, so that Confederate troops could not be hurried in by rail, the Federal army would advance rapidly into East Tennessee, finish the destruction of the railroad and protect the bridge burners and all other loyal people.

— History of the Thirteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry, U.S.A. (1903)

After Stover and twenty-odd men under his command overwhelmed the Confederate guards, they lit up with strategically significant bridge, which carried trains of the East Tennessee, Virginia, and Georgia Railroad, by ignition of turpentine and pine knots.[5] The telegraph lines were also cut.[6] However, the United States Army did not come marching in to East Tennessee, and Confederate Secretary of War Judah Benjamin ordered that any captured bridge burners be put to death. To live and fight another day, the bridge burners retreated into the hills.[6] Stover and his allies lived for months in the Pond Mountains in eastern Carter County.[7]

Amidst the ongoing conflict, Daniel Stover remained in hiding in the wilderness through the cold and wet winter of 1861–62. Stover was eventually permitted to come home "on parole" due to intercessions on his behalf by Confederate-aligned friends.[8] In October 1862 the Stovers, Eliza and Frank Johnson were driven out of their Carter County home and sent to Murfreesboro.[9] After they left, the residence and farm buildings were pillaged.[10] The Stovers, accompanied by Eliza, moved around a bit in early 1863, staying for a time in Indiana and in Louisville, Kentucky.[11] Col. Stover organized the Fourth Regiment of Tennessee Volunteer Infantry at Louisville in spring 1863.[12] The family travelled together to Nashville arriving May 30, 1863, where Col. and Mrs. Stover, Eliza and Andrew Johnson were welcomed by a large crowd.[11] However, due to chronic health problems from his time in the wilderness, Stover "did not see much active service in the field," and resigned from the United States Army on August 10, 1864, due to illness.[12] He died at Nashville just before Christmas of that year. Per a 1903 regimental history, "When the war came he was an extensive slave holder, but, like a true patriot, he was willing to give up all for his country."[13] "Daniel Stover's Sixteen Heirs," seemingly referring to Dan Stover's paternal grandfather Daniel Stover I, collectively owned nine slaves in Carter County, Tennessee at the time of the 1860 U.S. federal census.[14]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Winston (1928), p. 97.

- ^ "Mary Stover in entry for Daniel Stover", United States Census, 1860 – via FamilySearch

- ^ Scott & Angel (1903), p. 65.

- ^ Storie (2013), p. 38.

- ^ Scott & Angel (1903), p. 70.

- ^ a b Storie (2013), p. 42.

- ^ Storie (2013), p. 52.

- ^ Holloway (1871), p. 636.

- ^ Trefousse (1989), p. 161.

- ^ Holloway (1871), p. 638.

- ^ a b Trefousse (1989), p. 168.

- ^ a b Scott & Angel (1903), p. 504.

- ^ Scott & Angel (1903), p. 510.

- ^ "Daniel Stover's Sixteen Heirs", United States Census (Slave Schedules), 1860 – via FamilySearch.org

Sources

edit- Holloway, Laura C. (1871). "Mary Stover". The Ladies of the White House. New York: United States Pub. Co. pp. 635–649. LCCN 04013417. OCLC 681133673. OL 13503123M – via HathiTrust (New York Public Library copy).

- Scott, Samuel W.; Angel, Samuel P (1903). History of the Thirteenth Regiment, Tennessee Volunteer Cavalry, U. S. A.: including a narrative of the bridge burning; the Carter County rebellion, and the loyalty, heroism and suffering of the Union men and women of Carter and Johnson counties, Tennessee, during the Civil War... Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler. LCCN 03008593. OCLC 771788381. OL 7064017M.

- Storie, Melanie (2013). The Dreaded Thirteenth Tennessee Union Cavalry: Marauding Mountain Men. Charleston, S.C.: The History Press. ISBN 9781625845665.

- Trefousse, Hans L. (1989). Andrew Johnson: A Biography (1st ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393026736. LCCN 88028295. OCLC 463084977.

- Winston, Robert W. (1928). Andrew Johnson, Plebeian and Patriot. New York: Henry Holt & Company. LCCN 28007534. OCLC 475518. OL 6712742M – via HathiTrust.