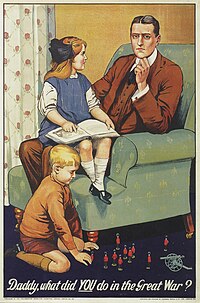

"Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was a British First World War recruitment poster by Savile Lumley, and first published in March 1915 by the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee. It was commissioned and submitted to the committee by Arthur Gunn, the director of the publishers Johnson Riddle and Company. The poster shows a daughter posing a question to her father: "Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?", depicting a future from the perspective of viewers in 1915. The poster implies the viewer will be seen as a coward by following generations if they do not contribute to the war, a message inspired by Gunn's own feelings of guilt around not fighting.

Poster no. PRC 79[1] | |

| Agency | Johnson Riddle & Co |

|---|---|

| Client | Parliamentary Recruiting Committee |

| Release date(s) | March 1915 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

Unlike other recruitment posters of the time which focused on more direct calls to action, the poster used indirect messaging to persuade men to enlist in the army at a time when conscription was not yet a policy in Great Britain. Although the poster is now considered an icon of British history during the First World War,[2] it was not one of the most circulated recruitment posters and there was some contemporary backlash to its message.

Background

editRecruitment for the First World War was different from prior wars, which had been fought by the regular professional army.[3] At the outbreak of war, Britain did not have a policy of conscription. The Parliamentary Recruitment Committee, chaired by the prime minister, Herbert Asquith, organised an extensive official recruitment campaign to encourage men to enlist.[4]

The number of new recruits declined from November 1914 to September 1915 as the optimism initially felt during the early period of the war declined.[5][6] The Parliamentary Recruitment Committee altered the approach taken by their posters, moving towards guilt and patriotism as motivators.[7] There were 1.4 million new volunteers in 1915, up from 1 million in 1914, and approximately 30 per cent of military-aged men had volunteered for military service.[8]

Publication history

edit"Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was neither designed nor commissioned by the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee.[9] In November 1914, a Voluntary Recruiting Publicity Committee was convened whose purpose was to unofficially design recruitment posters and submit the works to the Army Council. The committee had seven members and was headed by publisher and advertising executive Hedley Le Bas. Some of the committee's posters were accepted for wider circulation and they also featured in donated sections of newspapers.[10]

The publication of "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was the result of iterations of posters with similar themes, designed by the committee.[11] Thomas Russell, advertising consultant and one of the members of the committee, designed a poster which was released in January 1915 titled "5 Questions to Men Who Have Not Enlisted". One of the questions, "What will you answer when your children grow up, and say, 'Father, why weren't you a soldier, too?'", impressed Le Bas, who approached a magazine to create a cartoon based on the slogan; the resulting strip featured the question "Daddy, why weren't you a soldier during the war?" accompanied with the subheading "In years to come you may be asked this question. Join the Army at once, and help to secure the glorious Empire of which your little son will be a citizen". A further iteration featured a boy scout asking the question: "Father, what did you do to help when Britain fought for freedom in 1915?"[11][12]

The idea for the poster "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" came from Arthur Gunn, the director of publishers Johnson Riddle and Company. He related to the message due to his own feelings of guilt, having not enlisted to fight. He commissioned artist John Savile Lumley[a] to create a poster which framed the question within a domestic setting. Upon seeing a sketch of the poster, Gunn signed up to the Westminster Volunteer Cavalry. Gunn took the poster to the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee who approved it for official publication as PRC no. 79.[14][11]

Design

editDescription

edit"Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" has a simple composition. A man sits on an armchair looking out at the viewer with a distant expression. A girl (his daughter) sits on his lap with a book, while a boy plays with toy soldiers on the floor near the chair.[15][16] The title, in white cursive text, is at the bottom of the poster. The image is surrounded by a black border.[17] The poster used a complicated printing process involving eight colour printings.[11] Unlike many other First World War recruitment posters, which were typified by simple imagery and words, Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" has more detailed drawings with an elegant design.[4]

Propaganda

editPsychology as a scientific discipline and the concept of advertising were both in their infancy at the start of the First World War.[15] The war necessitated a use for psychological advertising—a method to control and influence the entire population, rather than targeting one specific audience for a commercial product.[16] "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was one of a number of posters which used psychology as a method to advertise the army to men.[15] In contrast to other recruitment posters which were a direct call to action, "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was less direct in its messaging.[2] The poster does not promise that the potential recruit's life upon enlisting will improve nor does it sell them anything; guilt is the main emotion pushed by the image.[18] Depicting a future from those viewing it in 1915, the poster assumes that men at the time would be thinking ahead to the future.[19] It implies that if they did not enlist, they would face humiliation back home, including from their own children.[20]

The poster's image of domesticity suggests to the viewer that men had to fight to preserve familial life.[21] Author Karyn Burnham writes that propaganda posters of the time "presented a carefully crafted image of manhood defining 'real' men as those who fought for their families, for King and Country". She cites this poster as an example of an image that prompted men to assess their self-worth.[22]

Reception

editAlthough "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" is now one of the most famous First World War recruitment posters,[23] it was not initially popular.[24] There were 13 other posters published by the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee in 15 March and "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was not selected to be published in newspapers or as a cigarette card. It was not among the most-produced posters by the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee.[1] The poster became famous after the war was over and became an icon of the war.[25] Nicholas Hiley writes that posters like Leete's "Kitchener Wants You" and Lumley's "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" are "famous because we want them to be famous, not because they give us access to the dominant emotions of the recruiting campaign".[26]

French historians Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau and Annette Becker have written that the campaign of propaganda during the war, including what they describe as the "guilt-inducing and brutal messages" such as "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was not the only reason that men signed up to fight. There is evidence that recruiters realised that the guilt-inducing approach may actually have been counterproductive.[27] "Daddy, What Did You Do in the Great War?" was not representative of how a lot of men and families perceived the war[24]—many working class people were not trusting of the recruitment campaign in general and other contemporary viewers disliked the over-confident messaging.[28] War opponents of the time scorned the poster and its shaming message. Robert Smillie, an Irish-born Scottish trade union leader, co-founder of the Scottish Labour Party, and a close friend of anti-war activist Keir Hardie, said that his reply to the question of the little girl in the poster would have been, "I tried to stop the bloody thing, my child."[29] Savile Lumley eventually renounced the poster due to the scale of criticism directed towards it.[17]

Men fighting on the front found dark humour in the poster's message,[17] with some hanging the poster up in the trenches where they served, often leaving graffitied answers to the daughter's question.[23][30] The poster was satirised in a poem published in the Lancashire Fusiliers' magazine:

What did you do in the Great War, Dad?

Please Daddy, tell us, do:

For they censor all your letters.

So we know they can't be true.[25]

In the year before the Second World War, artist E. H. Shepard parodied the poster in a cartoon drawn in opposition to the policy of appeasement: "What are you going to do in the Great Peace, Daddy?"[31]

See also

edit- British propaganda during World War I

- Lord Kitchener Wants You

- What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?, a 1966 American comedy film

References

editNotes

editCitations

edit- ^ a b Hiley 1997, p. 42.

- ^ a b Hiley 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Hynes, Samuel (1 April 1998). The Soldiers' Tale: Bearing Witness to Modern War. Penguin. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-101-19172-9.

- ^ a b "'Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?', a British recruitment poster". British Library. Archived from the original on 4 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Hiley 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Bownes & Fleming 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Bownes & Fleming 2014, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Audoin-Rouzeau & Becker 2002, p. 98.

- ^ Bownes & Fleming 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Hiley 1997, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c d Hiley 1997, p. 46.

- ^ "What Will Your Answer Be – What Did You Do to Help When Britain Fought for Freedom in 1915?". Imperial War Museums. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ Peppin, Micklethwait & Arco Publishing 1984, p. 187.

- ^ "Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?". Victoria and Albert Museum Collections. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Dyer 1982, p. 43.

- ^ a b Moeran 2010, p. 141.

- ^ a b c "Daddy, what did You do in the Great War?". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Shore 2012, p. 93.

- ^ Fussell 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Ball 2020, p. 16.

- ^ Dyer 1982, p. 45.

- ^ Burnham 2014, p. 1.

- ^ a b "Daddy, what did you do in the Great War?". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ a b Hiley 1997, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b Hiley 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Hiley 1997, p. 55.

- ^ Audoin-Rouzeau & Becker 2002, p. 99.

- ^ Hiley 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Hochschild 2011, p. 151.

- ^ Bownes & Fleming 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Bryant 2014.

Works cited

edit- Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane; Becker, Annette (2002). 14–18, understanding the Great War. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0-8090-4643-1. OCLC 51206451.

- Ball, Rebecca (2020). "'Birmingham clapped her hands with the rest of the world, welcoming the signs of peace': Working-Class Urban Childhoods in Birmingham, London and Greater Manchester During the First World War". In Andrews, Maggie; Fleming, N. C.; Morris, Marcus (eds.). Histories, Memories and Representations of being Young in the First World War. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave MacMillan. pp. 11–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49939-6_2. ISBN 978-3-030-49939-6. OCLC 1199891174. S2CID 226457558.

- Bownes, David; Fleming, Robert (2014). Posters of the first world war. Oxford: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-1538-9. OCLC 888381885.

- Bryant, Mark (2014). "Your country needs YOU...". British Journalism Review. 25 (4). SAGE Publications: 61–67. doi:10.1177/0956474814562775. ISSN 0956-4748. S2CID 147179430.

- Burnham, Karyn (2014). The courage of cowards : the untold stories of First World War conscientious objectors. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-3675-4. OCLC 894792004.

- Dyer, Gillian (1982). Advertising as communication. London: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-74520-2. OCLC 8494460.

- Fussell, Paul (2009). The Great War and modern memory. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-6439-4. OCLC 311760334.

- Hiley, Nicholas (1997). "'Kitchener wants you' and 'Daddy, what did YOU do in the Great War?' The myth of British recruiting posters". Imperial War Museum Review (11): 40–58.

- Hochschild, Adam (2011). To end all wars : a story of loyalty and rebellion, 1914–1918. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-75828-9. OCLC 646308293.

- Moeran, Brian (2010). Advertising : critical readings. Oxford: Berg. ISBN 978-1-84788-559-3. OCLC 526591293.

- Peppin, Brigid; Micklethwait, Lucy; Arco Publishing (1984). Book illustrators of the twentieth century. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 0-668-05670-3. OCLC 9324664.

- Shore, Robert (2012). 10 advertising principles. London: Vivays. ISBN 978-1-908126-30-6. OCLC 795182449.