Contestani (Ancient Greek: Κοντεστανοί) is an ethnonym of Roman Spain of the imperial period. It appears chiefly in the Greco-Roman writers Pliny the Elder (Natural History (Pliny) iii.iii.19-20), 1st century, and Claudius Ptolemy (The Geography ii.5 on Hispania Tarraconensis), 2nd century. Pliny might be considered the more creditable, as he was for a time procurator of the official Hispania Tarraconensis, a province of the Roman Empire encompassing all the north and all the east of the Iberian Peninsula (the chief part of the future nation of Spain).[2]

Unknown | |

|---|---|

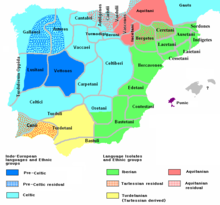

Greco-Roman ethnography of the Iberian Peninsula after its occupation by Romans on the defeat of the Carthaginians. A good approximate date is 200 BC. The green represents the Iberian-speaking population. In that region the Romans applied different ethnonymns of their own devise. On what basis they did so or how closely they match any native names remains unknown. The names are often incorrectly interpreted as pre-Roman (they are Roman) or as the names of paleohispanic ethnic groups. Whether they might be or what they might be are not known. The only known paleohispanic group is the population of Iberian speakers. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| |

| Languages | |

| Iberian, Phoenician, Greek, Latin | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Bastuli, Bastetani, Oretani, Edetani, Ilercavones, Cessetani, Laietani, Lacetani, Indigetes, Ausetani, Sordones |

A geographic ethnonym from ancient times, however, was not necessarily the name of a people. It might be a toponym. Perhaps the name of the supposed people came from the name of the place. In that case, anyone could live in the place and be counted as one of its people without the necessity to belong to an ingroup such as a tribe. L. A. Curchin did an etymological study of all the ancient names in Contestani and Edetani to the north of it. The implied distribution was multilingual and therefore multiethnic: 14% Iberian, 3% Punic, 35% Indo-European, including 19% Greek and 18% Latin, the rest uncertain.[3]

An earlier literary fragment presents the same system. Livy, historian living in the Augustan period, writes in a fragment of Book 91 describing the revolt of the Iberian people under Quintus Sertorius against Rome under Sulla, calls Ilercavonia and Contestania both gentes, "peoples" (a well-known word in Spanish). Here he uses the toponyms ending in -ia for the ethnics, equating place and people.

The ethno/topo-nyms are made to fit into the grammatical contexts of the Greco-Latin sources just as though they were Latin words. They give the appearance of being Latin, and seem to contain segments of Latin. One is tempted to see contest in Contestania as though they were some sort of tribe that likes to contend. Similarly the Oretani might be mountain (Greek ore) men, and the Lacetani some sort of Lacedaemonian, while the Indigetes stand in place of the Indigenes (natives). -Tani looks like the -istan suffix as in Pakistan.

However, the word formation is all wrong. The Greeks and Romans did not form words in that way. In all the body of Greek and Latin words, these are the only instances of these words, nor does searching the Indo-European roots help. Moreover, there is nothing like them at all in the Iberian vocabulary. At a loss for any other explanation, the scholars fall back on the theory that the Roman soldiers invented these words to imitate the foreign language that they heard there. A famous modern example is the rendering of Reykjavík Iceland into rinkey-dink by the allied troops passing through. Llobregat says:[4]

We know nothing of the meaning of these geographical names that the Roman invader probably forged on indigenous gentiles. Recent research attempts to unravel the meaning of these terms, which often, as in the present case, have only very late literary documentation, at a time when the country was completely Romanized. ... but what is their significance? For the time being, it is unknown to us, ... There is only one way left open that allows us to identify these compartmentalizations in some way, ... a geographical analysis. ... In a word, to try to identify a homogeneous and reasonable territory that could serve as the basis for the concept of the ancient administrative division.

The real name, if any, of the people was not known. Accordingly, Llobregat chose for the name of the people and the book, Contestania Iberica, meaning the Iberian territory that would become Contestania. Observing that the culture evolved into this role, he coined the term Contestanianization.

Geography

editGreco-Roman

editThey lived in a region located in the southwest of Hispania Tarraconensis, east of the territory of the Bastetani, between the city of Urci, located NE of the Baetica and river Sucro, today known as Júcar.

Cartago Nova was within its territory. Other important towns were Setabi (Xàtiva), Lucenti or Lucentum (La Albufereta in Alicante), Alonis (Villajoyosa), Ilici (Elche), Menlaria, Valentia and Iaspis.

Iberian

editIberian coins were minted at Setabi.[5]

Archaeology

editImportant Contestani archaeological sites include Tolmo de Minateda hill near Hellín and Bastida de les Alcusses, near Mogente.[6]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Abad Casal 2005, p. 11 "Llobregat proposed a model for Contestania that it was limited to an area bounded by the rivers Júcar, Segura and Viña lopó, despite the fact that it was already known at that time that ... the sources seemed to point to the fact that the area through which this culture was spreading ... was considerably broader; today we can add that some of its characteristic elements far exceed the limits proposed by Enrique Llobregat."

- ^ Smith, Philip (1854). "Contestani". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Perseus Digital Library.

- ^ Curchin 2009, p. 73

- ^ Llobregat Conesa, Enrique (1972). Contestania Iberica (PDF) (in Spanish). Alicante: Instituto de Estudios Alicantinos. p. 9.

- ^ José Uroz Sáez, Economía y sociedad de Contestania ibérica, Instituto de estudios alicantinos,1998. ISBN 84-00-04959-4

- ^ Abad Casal L, Gutiérrez Lloret S, Sanz Gamo R. El Tolmo de Minateda. Una historia de tres mil quinientos años. Junta de Comunidades de Castilla La Mancha, Toledo, 1999

Reference bibliography

edit- Abad Casal, Lorenzo (2005). "La Contestania Ibérica, treinta años después". In Abad, Lorenzo; Sala, Feliciana; Grau, Ignacio (eds.). La Contestania Ibérica, treinta años después (in Spanish). San Vicente: Universidad de Alicante, Servicio de Publicaciones. ISBN 84-7908-845-1.

- Curchin, Leonard (2009). "La toponimia antigua de Contestania y Edetania". Lucentum (in Spanish). 28.

- Ángel Montenegro et alii, Historia de España 2 - colonizaciones y formación de los pueblos prerromanos (1200-218 a.C), Editorial Gredos, Madrid (1989) ISBN 84-249-1386-8