In mathematics, a complex number is an element of a number system that extends the real numbers with a specific element denoted i, called the imaginary unit and satisfying the equation ; every complex number can be expressed in the form , where a and b are real numbers. Because no real number satisfies the above equation, i was called an imaginary number by René Descartes. For the complex number , a is called the real part, and b is called the imaginary part. The set of complex numbers is denoted by either of the symbols or C. Despite the historical nomenclature, "imaginary" complex numbers have a mathematical existence as firm as that of the real numbers, and they are fundamental tools in the scientific description of the natural world.[1][2]

Complex numbers allow solutions to all polynomial equations, even those that have no solutions in real numbers. More precisely, the fundamental theorem of algebra asserts that every non-constant polynomial equation with real or complex coefficients has a solution which is a complex number. For example, the equation has no real solution, because the square of a real number cannot be negative, but has the two nonreal complex solutions and .

Addition, subtraction and multiplication of complex numbers can be naturally defined by using the rule along with the associative, commutative, and distributive laws. Every nonzero complex number has a multiplicative inverse. This makes the complex numbers a field with the real numbers as a subfield.

The complex numbers also form a real vector space of dimension two, with as a standard basis. This standard basis makes the complex numbers a Cartesian plane, called the complex plane. This allows a geometric interpretation of the complex numbers and their operations, and conversely some geometric objects and operations can be expressed in terms of complex numbers. For example, the real numbers form the real line, which is pictured as the horizontal axis of the complex plane, while real multiples of are the vertical axis. A complex number can also be defined by its geometric polar coordinates: the radius is called the absolute value of the complex number, while the angle from the positive real axis is called the argument of the complex number. The complex numbers of absolute value one form the unit circle. Adding a fixed complex number to all complex numbers defines a translation in the complex plane, and multiplying by a fixed complex number is a similarity centered at the origin (dilating by the absolute value, and rotating by the argument). The operation of complex conjugation is the reflection symmetry with respect to the real axis.

The complex numbers form a rich structure that is simultaneously an algebraically closed field, a commutative algebra over the reals, and a Euclidean vector space of dimension two.

Definition and basic operations

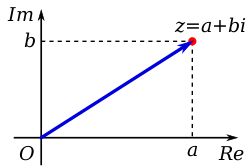

editA complex number is an expression of the form a + bi, where a and b are real numbers, and i is an abstract symbol, the so-called imaginary unit, whose meaning will be explained further below. For example, 2 + 3i is a complex number.[3]

For a complex number a + bi, the real number a is called its real part , and the real number b (not the complex number bi) is its imaginary part.[4][5] The real part of a complex number z is denoted Re(z), , or ; the imaginary part is Im(z), , or : for example, , .

A complex number z can be identified with the ordered pair of real numbers , which may be interpreted as coordinates of a point in a Euclidean plane with standard coordinates, which is then called the complex plane or Argand diagram,[6][a].[7] The horizontal axis is generally used to display the real part, with increasing values to the right, and the imaginary part marks the vertical axis, with increasing values upwards.

A real number a can be regarded as a complex number a + 0i, whose imaginary part is 0. A purely imaginary number bi is a complex number 0 + bi, whose real part is zero. As with polynomials, it is common to write a + 0i = a, 0 + bi = bi, and a + (−b)i = a − bi; for example, 3 + (−4)i = 3 − 4i.

The set of all complex numbers is denoted by (blackboard bold) or C (upright bold).

In some disciplines such as electromagnetism and electrical engineering, j is used instead of i, as i frequently represents electric current,[8][9] and complex numbers are written as a + bj or a + jb.

Addition and subtraction

editTwo complex numbers and are added by separately adding their real and imaginary parts. That is to say:

Similarly, subtraction can be performed as

The addition can be geometrically visualized as follows: the sum of two complex numbers a and b, interpreted as points in the complex plane, is the point obtained by building a parallelogram from the three vertices O, and the points of the arrows labeled a and b (provided that they are not on a line). Equivalently, calling these points A, B, respectively and the fourth point of the parallelogram X the triangles OAB and XBA are congruent.

Multiplication

editThe product of two complex numbers is computed as follows:

For example, In particular, this includes as a special case the fundamental formula

This formula distinguishes the complex number i from any real number, since the square of any (negative or positive) real number is always a non-negative real number.

With this definition of multiplication and addition, familiar rules for the arithmetic of rational or real numbers continue to hold for complex numbers. More precisely, the distributive property, the commutative properties (of addition and multiplication) hold. Therefore, the complex numbers form an algebraic structure known as a field, the same way as the rational or real numbers do.[10]

Complex conjugate, absolute value, argument and division

editThe complex conjugate of the complex number z = x + yi is defined as [11] It is also denoted by some authors by . Geometrically, z is the "reflection" of z about the real axis. Conjugating twice gives the original complex number: A complex number is real if and only if it equals its own conjugate. The unary operation of taking the complex conjugate of a complex number cannot be expressed by applying only their basic operations addition, subtraction, multiplication and division.

For any complex number z = x + yi , the product

is a non-negative real number. This allows to define the absolute value (or modulus or magnitude) of z to be the square root[12] By Pythagoras' theorem, is the distance from the origin to the point representing the complex number z in the complex plane. In particular, the circle of radius one around the origin consists precisely of the numbers z such that . If is a real number, then : its absolute value as a complex number and as a real number are equal.

Using the conjugate, the reciprocal of a nonzero complex number can be computed to be

More generally, the division of an arbitrary complex number by a non-zero complex number equals This process is sometimes called "rationalization" of the denominator (although the denominator in the final expression may be an irrational real number), because it resembles the method to remove roots from simple expressions in a denominator.[13][14]

The argument of z (sometimes called the "phase" φ)[7] is the angle of the radius Oz with the positive real axis, and is written as arg z, expressed in radians in this article. The angle is defined only up to adding integer multiples of , since a rotation by (or 360°) around the origin leaves all points in the complex plane unchanged. One possible choice to uniquely specify the argument is to require it to be within the interval , which is referred to as the principal value.[15] The argument can be computed from the rectangular form x + yi by means of the arctan (inverse tangent) function.[16]

Polar form

editFor any complex number z, with absolute value and argument , the equation

holds. This identity is referred to as the polar form of z. It is sometimes abbreviated as . In electronics, one represents a phasor with amplitude r and phase φ in angle notation:[17]

If two complex numbers are given in polar form, i.e., z1 = r1(cos φ1 + i sin φ1) and z2 = r2(cos φ2 + i sin φ2), the product and division can be computed as (These are a consequence of the trigonometric identities for the sine and cosine function.) In other words, the absolute values are multiplied and the arguments are added to yield the polar form of the product. The picture at the right illustrates the multiplication of Because the real and imaginary part of 5 + 5i are equal, the argument of that number is 45 degrees, or π/4 (in radian). On the other hand, it is also the sum of the angles at the origin of the red and blue triangles are arctan(1/3) and arctan(1/2), respectively. Thus, the formula holds. As the arctan function can be approximated highly efficiently, formulas like this – known as Machin-like formulas – are used for high-precision approximations of π:[18]

Powers and roots

editThe n-th power of a complex number can be computed using de Moivre's formula, which is obtained by repeatedly applying the above formula for the product: For example, the first few powers of the imaginary unit i are .

The n nth roots of a complex number z are given by for 0 ≤ k ≤ n − 1. (Here is the usual (positive) nth root of the positive real number r.) Because sine and cosine are periodic, other integer values of k do not give other values. For any , there are, in particular n distinct complex n-th roots. For example, there are 4 fourth roots of 1, namely

In general there is no natural way of distinguishing one particular complex nth root of a complex number. (This is in contrast to the roots of a positive real number x, which has a unique positive real n-th root, which is therefore commonly referred to as the n-th root of x.) One refers to this situation by saying that the nth root is a n-valued function of z.

Fundamental theorem of algebra

editThe fundamental theorem of algebra, of Carl Friedrich Gauss and Jean le Rond d'Alembert, states that for any complex numbers (called coefficients) a0, ..., an, the equation has at least one complex solution z, provided that at least one of the higher coefficients a1, ..., an is nonzero.[19] This property does not hold for the field of rational numbers (the polynomial x2 − 2 does not have a rational root, because √2 is not a rational number) nor the real numbers (the polynomial x2 + 4 does not have a real root, because the square of x is positive for any real number x).

Because of this fact, is called an algebraically closed field. It is a cornerstone of various applications of complex numbers, as is detailed further below. There are various proofs of this theorem, by either analytic methods such as Liouville's theorem, or topological ones such as the winding number, or a proof combining Galois theory and the fact that any real polynomial of odd degree has at least one real root.

History

editThe solution in radicals (without trigonometric functions) of a general cubic equation, when all three of its roots are real numbers, contains the square roots of negative numbers, a situation that cannot be rectified by factoring aided by the rational root test, if the cubic is irreducible; this is the so-called casus irreducibilis ("irreducible case"). This conundrum led Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano to conceive of complex numbers in around 1545 in his Ars Magna,[20] though his understanding was rudimentary; moreover, he later described complex numbers as being "as subtle as they are useless".[21] Cardano did use imaginary numbers, but described using them as "mental torture."[22] This was prior to the use of the graphical complex plane. Cardano and other Italian mathematicians, notably Scipione del Ferro, in the 1500s created an algorithm for solving cubic equations which generally had one real solution and two solutions containing an imaginary number. Because they ignored the answers with the imaginary numbers, Cardano found them useless.[23]

Work on the problem of general polynomials ultimately led to the fundamental theorem of algebra, which shows that with complex numbers, a solution exists to every polynomial equation of degree one or higher. Complex numbers thus form an algebraically closed field, where any polynomial equation has a root.

Many mathematicians contributed to the development of complex numbers. The rules for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and root extraction of complex numbers were developed by the Italian mathematician Rafael Bombelli.[24] A more abstract formalism for the complex numbers was further developed by the Irish mathematician William Rowan Hamilton, who extended this abstraction to the theory of quaternions.[25]

The earliest fleeting reference to square roots of negative numbers can perhaps be said to occur in the work of the Greek mathematician Hero of Alexandria in the 1st century AD, where in his Stereometrica he considered, apparently in error, the volume of an impossible frustum of a pyramid to arrive at the term in his calculations, which today would simplify to .[b] Negative quantities were not conceived of in Hellenistic mathematics and Hero merely replaced it by its positive [27]

The impetus to study complex numbers as a topic in itself first arose in the 16th century when algebraic solutions for the roots of cubic and quartic polynomials were discovered by Italian mathematicians (Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia and Gerolamo Cardano). It was soon realized (but proved much later)[28] that these formulas, even if one were interested only in real solutions, sometimes required the manipulation of square roots of negative numbers. In fact, it was proved later that the use of complex numbers is unavoidable when all three roots are real and distinct.[c] However, the general formula can still be used in this case, with some care to deal with the ambiguity resulting from the existence of three cubic roots for nonzero complex numbers. Rafael Bombelli was the first to address explicitly these seemingly paradoxical solutions of cubic equations and developed the rules for complex arithmetic, trying to resolve these issues.

The term "imaginary" for these quantities was coined by René Descartes in 1637, who was at pains to stress their unreal nature:[29]

... sometimes only imaginary, that is one can imagine as many as I said in each equation, but sometimes there exists no quantity that matches that which we imagine.

[... quelquefois seulement imaginaires c'est-à-dire que l'on peut toujours en imaginer autant que j'ai dit en chaque équation, mais qu'il n'y a quelquefois aucune quantité qui corresponde à celle qu'on imagine.]

A further source of confusion was that the equation seemed to be capriciously inconsistent with the algebraic identity , which is valid for non-negative real numbers a and b, and which was also used in complex number calculations with one of a, b positive and the other negative. The incorrect use of this identity in the case when both a and b are negative, and the related identity , even bedeviled Leonhard Euler. This difficulty eventually led to the convention of using the special symbol i in place of to guard against this mistake.[30][31] Even so, Euler considered it natural to introduce students to complex numbers much earlier than we do today. In his elementary algebra text book, Elements of Algebra, he introduces these numbers almost at once and then uses them in a natural way throughout.

In the 18th century complex numbers gained wider use, as it was noticed that formal manipulation of complex expressions could be used to simplify calculations involving trigonometric functions. For instance, in 1730 Abraham de Moivre noted that the identities relating trigonometric functions of an integer multiple of an angle to powers of trigonometric functions of that angle could be re-expressed by the following de Moivre's formula:

In 1748, Euler went further and obtained Euler's formula of complex analysis:[32]

by formally manipulating complex power series and observed that this formula could be used to reduce any trigonometric identity to much simpler exponential identities.

The idea of a complex number as a point in the complex plane (above) was first described by Danish–Norwegian mathematician Caspar Wessel in 1799,[33] although it had been anticipated as early as 1685 in Wallis's A Treatise of Algebra.[34]

Wessel's memoir appeared in the Proceedings of the Copenhagen Academy but went largely unnoticed. In 1806 Jean-Robert Argand independently issued a pamphlet on complex numbers and provided a rigorous proof of the fundamental theorem of algebra.[35] Carl Friedrich Gauss had earlier published an essentially topological proof of the theorem in 1797 but expressed his doubts at the time about "the true metaphysics of the square root of −1".[36] It was not until 1831 that he overcame these doubts and published his treatise on complex numbers as points in the plane,[37] largely establishing modern notation and terminology:[38]

If one formerly contemplated this subject from a false point of view and therefore found a mysterious darkness, this is in large part attributable to clumsy terminology. Had one not called +1, −1, positive, negative, or imaginary (or even impossible) units, but instead, say, direct, inverse, or lateral units, then there could scarcely have been talk of such darkness.

In the beginning of the 19th century, other mathematicians discovered independently the geometrical representation of the complex numbers: Buée,[39][40] Mourey,[41] Warren,[42][43][44] Français and his brother, Bellavitis.[45][46]

The English mathematician G.H. Hardy remarked that Gauss was the first mathematician to use complex numbers in "a really confident and scientific way" although mathematicians such as Norwegian Niels Henrik Abel and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi were necessarily using them routinely before Gauss published his 1831 treatise.[47]

Augustin-Louis Cauchy and Bernhard Riemann together brought the fundamental ideas of complex analysis to a high state of completion, commencing around 1825 in Cauchy's case.

The common terms used in the theory are chiefly due to the founders. Argand called cos φ + i sin φ the direction factor, and the modulus;[d][48] Cauchy (1821) called cos φ + i sin φ the reduced form (l'expression réduite)[49] and apparently introduced the term argument; Gauss used i for ,[e] introduced the term complex number for a + bi,[f] and called a2 + b2 the norm.[g] The expression direction coefficient, often used for cos φ + i sin φ, is due to Hankel (1867),[53] and absolute value, for modulus, is due to Weierstrass.

Later classical writers on the general theory include Richard Dedekind, Otto Hölder, Felix Klein, Henri Poincaré, Hermann Schwarz, Karl Weierstrass and many others. Important work (including a systematization) in complex multivariate calculus has been started at beginning of the 20th century. Important results have been achieved by Wilhelm Wirtinger in 1927.

Abstract algebraic aspects

editWhile the above low-level definitions, including the addition and multiplication, accurately describes the complex numbers, there are other, equivalent approaches that reveal the abstract algebraic structure of the complex numbers more immediately.

Construction as a quotient field

editOne approach to is via polynomials, i.e., expressions of the form where the coefficients a0, ..., an are real numbers. The set of all such polynomials is denoted by . Since sums and products of polynomials are again polynomials, this set forms a commutative ring, called the polynomial ring (over the reals). To every such polynomial p, one may assign the complex number , i.e., the value obtained by setting . This defines a function

This function is surjective since every complex number can be obtained in such a way: the evaluation of a linear polynomial at is . However, the evaluation of polynomial at i is 0, since This polynomial is irreducible, i.e., cannot be written as a product of two linear polynomials. Basic facts of abstract algebra then imply that the kernel of the above map is an ideal generated by this polynomial, and that the quotient by this ideal is a field, and that there is an isomorphism

between the quotient ring and . Some authors take this as the definition of .[54]

Accepting that is algebraically closed, because it is an algebraic extension of in this approach, is therefore the algebraic closure of

Matrix representation of complex numbers

editComplex numbers a + bi can also be represented by 2 × 2 matrices that have the form Here the entries a and b are real numbers. As the sum and product of two such matrices is again of this form, these matrices form a subring of the ring of 2 × 2 matrices.

A simple computation shows that the map is a ring isomorphism from the field of complex numbers to the ring of these matrices, proving that these matrices form a field. This isomorphism associates the square of the absolute value of a complex number with the determinant of the corresponding matrix, and the conjugate of a complex number with the transpose of the matrix.

The geometric description of the multiplication of complex numbers can also be expressed in terms of rotation matrices by using this correspondence between complex numbers and such matrices. The action of the matrix on a vector (x, y) corresponds to the multiplication of x + iy by a + ib. In particular, if the determinant is 1, there is a real number t such that the matrix has the form

In this case, the action of the matrix on vectors and the multiplication by the complex number are both the rotation of the angle t.

Complex analysis

editThe study of functions of a complex variable is known as complex analysis and has enormous practical use in applied mathematics as well as in other branches of mathematics. Often, the most natural proofs for statements in real analysis or even number theory employ techniques from complex analysis (see prime number theorem for an example).

Unlike real functions, which are commonly represented as two-dimensional graphs, complex functions have four-dimensional graphs and may usefully be illustrated by color-coding a three-dimensional graph to suggest four dimensions, or by animating the complex function's dynamic transformation of the complex plane.

Convergence

editThe notions of convergent series and continuous functions in (real) analysis have natural analogs in complex analysis. A sequence of complex numbers is said to converge if and only if its real and imaginary parts do. This is equivalent to the (ε, δ)-definition of limits, where the absolute value of real numbers is replaced by the one of complex numbers. From a more abstract point of view, , endowed with the metric is a complete metric space, which notably includes the triangle inequality for any two complex numbers z1 and z2.

Complex exponential

editLike in real analysis, this notion of convergence is used to construct a number of elementary functions: the exponential function exp z, also written ez, is defined as the infinite series, which can be shown to converge for any z: For example, is Euler's number . Euler's formula states: for any real number φ. This formula is a quick consequence of general basic facts about convergent power series and the definitions of the involved functions as power series. As a special case, this includes Euler's identity

Complex logarithm

editFor any positive real number t, there is a unique real number x such that . This leads to the definition of the natural logarithm as the inverse of the exponential function. The situation is different for complex numbers, since

by the functional equation and Euler's identity. For example, eiπ = e3iπ = −1 , so both iπ and 3iπ are possible values for the complex logarithm of −1.

In general, given any non-zero complex number w, any number z solving the equation

is called a complex logarithm of w, denoted . It can be shown that these numbers satisfy where is the argument defined above, and the (real) natural logarithm. As arg is a multivalued function, unique only up to a multiple of 2π, log is also multivalued. The principal value of log is often taken by restricting the imaginary part to the interval (−π, π]. This leads to the complex logarithm being a bijective function taking values in the strip (that is denoted in the above illustration)

If is not a non-positive real number (a positive or a non-real number), the resulting principal value of the complex logarithm is obtained with −π < φ < π. It is an analytic function outside the negative real numbers, but it cannot be prolongated to a function that is continuous at any negative real number , where the principal value is ln z = ln(−z) + iπ.[h]

Complex exponentiation zω is defined as and is multi-valued, except when ω is an integer. For ω = 1 / n, for some natural number n, this recovers the non-uniqueness of nth roots mentioned above. If z > 0 is real (and ω an arbitrary complex number), one has a preferred choice of , the real logarithm, which can be used to define a preferred exponential function.

Complex numbers, unlike real numbers, do not in general satisfy the unmodified power and logarithm identities, particularly when naïvely treated as single-valued functions; see failure of power and logarithm identities. For example, they do not satisfy Both sides of the equation are multivalued by the definition of complex exponentiation given here, and the values on the left are a subset of those on the right.

Complex sine and cosine

editThe series defining the real trigonometric functions sine and cosine, as well as the hyperbolic functions sinh and cosh, also carry over to complex arguments without change. For the other trigonometric and hyperbolic functions, such as tangent, things are slightly more complicated, as the defining series do not converge for all complex values. Therefore, one must define them either in terms of sine, cosine and exponential, or, equivalently, by using the method of analytic continuation.

Holomorphic functions

editA function → is called holomorphic or complex differentiable at a point if the limit

exists (in which case it is denoted by ). This mimics the definition for real differentiable functions, except that all quantities are complex numbers. Loosely speaking, the freedom of approaching in different directions imposes a much stronger condition than being (real) differentiable. For example, the function

is differentiable as a function , but is not complex differentiable. A real differentiable function is complex differentiable if and only if it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann equations, which are sometimes abbreviated as

Complex analysis shows some features not apparent in real analysis. For example, the identity theorem asserts that two holomorphic functions f and g agree if they agree on an arbitrarily small open subset of . Meromorphic functions, functions that can locally be written as f(z)/(z − z0)n with a holomorphic function f, still share some of the features of holomorphic functions. Other functions have essential singularities, such as sin(1/z) at z = 0.

Applications

editComplex numbers have applications in many scientific areas, including signal processing, control theory, electromagnetism, fluid dynamics, quantum mechanics, cartography, and vibration analysis. Some of these applications are described below.

Complex conjugation is also employed in inversive geometry, a branch of geometry studying reflections more general than ones about a line. In the network analysis of electrical circuits, the complex conjugate is used in finding the equivalent impedance when the maximum power transfer theorem is looked for.

Geometry

editShapes

editThree non-collinear points in the plane determine the shape of the triangle . Locating the points in the complex plane, this shape of a triangle may be expressed by complex arithmetic as The shape of a triangle will remain the same, when the complex plane is transformed by translation or dilation (by an affine transformation), corresponding to the intuitive notion of shape, and describing similarity. Thus each triangle is in a similarity class of triangles with the same shape.[55]

Fractal geometry

editThe Mandelbrot set is a popular example of a fractal formed on the complex plane. It is defined by plotting every location where iterating the sequence does not diverge when iterated infinitely. Similarly, Julia sets have the same rules, except where remains constant.

Triangles

editEvery triangle has a unique Steiner inellipse – an ellipse inside the triangle and tangent to the midpoints of the three sides of the triangle. The foci of a triangle's Steiner inellipse can be found as follows, according to Marden's theorem:[56][57] Denote the triangle's vertices in the complex plane as a = xA + yAi, b = xB + yBi, and c = xC + yCi. Write the cubic equation , take its derivative, and equate the (quadratic) derivative to zero. Marden's theorem says that the solutions of this equation are the complex numbers denoting the locations of the two foci of the Steiner inellipse.

Algebraic number theory

editAs mentioned above, any nonconstant polynomial equation (in complex coefficients) has a solution in . A fortiori, the same is true if the equation has rational coefficients. The roots of such equations are called algebraic numbers – they are a principal object of study in algebraic number theory. Compared to , the algebraic closure of , which also contains all algebraic numbers, has the advantage of being easily understandable in geometric terms. In this way, algebraic methods can be used to study geometric questions and vice versa. With algebraic methods, more specifically applying the machinery of field theory to the number field containing roots of unity, it can be shown that it is not possible to construct a regular nonagon using only compass and straightedge – a purely geometric problem.

Another example is the Gaussian integers; that is, numbers of the form x + iy, where x and y are integers, which can be used to classify sums of squares.

Analytic number theory

editAnalytic number theory studies numbers, often integers or rationals, by taking advantage of the fact that they can be regarded as complex numbers, in which analytic methods can be used. This is done by encoding number-theoretic information in complex-valued functions. For example, the Riemann zeta function ζ(s) is related to the distribution of prime numbers.

Improper integrals

editIn applied fields, complex numbers are often used to compute certain real-valued improper integrals, by means of complex-valued functions. Several methods exist to do this; see methods of contour integration.

Dynamic equations

editIn differential equations, it is common to first find all complex roots r of the characteristic equation of a linear differential equation or equation system and then attempt to solve the system in terms of base functions of the form f(t) = ert. Likewise, in difference equations, the complex roots r of the characteristic equation of the difference equation system are used, to attempt to solve the system in terms of base functions of the form f(t) = rt.

Linear algebra

editSince is algebraically closed, any non-empty complex square matrix has at least one (complex) eigenvalue. By comparison, real matrices do not always have real eigenvalues, for example rotation matrices (for rotations of the plane for angles other than 0° or 180°) leave no direction fixed, and therefore do not have any real eigenvalue. The existence of (complex) eigenvalues, and the ensuing existence of eigendecomposition is a useful tool for computing matrix powers and matrix exponentials.

Complex numbers often generalize concepts originally conceived in the real numbers. For example, the conjugate transpose generalizes the transpose, hermitian matrices generalize symmetric matrices, and unitary matrices generalize orthogonal matrices.

In applied mathematics

editControl theory

editIn control theory, systems are often transformed from the time domain to the complex frequency domain using the Laplace transform. The system's zeros and poles are then analyzed in the complex plane. The root locus, Nyquist plot, and Nichols plot techniques all make use of the complex plane.

In the root locus method, it is important whether zeros and poles are in the left or right half planes, that is, have real part greater than or less than zero. If a linear, time-invariant (LTI) system has poles that are

- in the right half plane, it will be unstable,

- all in the left half plane, it will be stable,

- on the imaginary axis, it will have marginal stability.

If a system has zeros in the right half plane, it is a nonminimum phase system.

Signal analysis

editComplex numbers are used in signal analysis and other fields for a convenient description for periodically varying signals. For given real functions representing actual physical quantities, often in terms of sines and cosines, corresponding complex functions are considered of which the real parts are the original quantities. For a sine wave of a given frequency, the absolute value |z| of the corresponding z is the amplitude and the argument arg z is the phase.

If Fourier analysis is employed to write a given real-valued signal as a sum of periodic functions, these periodic functions are often written as complex-valued functions of the form

and

where ω represents the angular frequency and the complex number A encodes the phase and amplitude as explained above.

This use is also extended into digital signal processing and digital image processing, which use digital versions of Fourier analysis (and wavelet analysis) to transmit, compress, restore, and otherwise process digital audio signals, still images, and video signals.

Another example, relevant to the two side bands of amplitude modulation of AM radio, is:

In physics

editElectromagnetism and electrical engineering

editIn electrical engineering, the Fourier transform is used to analyze varying voltages and currents. The treatment of resistors, capacitors, and inductors can then be unified by introducing imaginary, frequency-dependent resistances for the latter two and combining all three in a single complex number called the impedance. This approach is called phasor calculus.

In electrical engineering, the imaginary unit is denoted by j, to avoid confusion with I, which is generally in use to denote electric current, or, more particularly, i, which is generally in use to denote instantaneous electric current.

Because the voltage in an AC circuit is oscillating, it can be represented as

To obtain the measurable quantity, the real part is taken:

The complex-valued signal V(t) is called the analytic representation of the real-valued, measurable signal v(t). [58]

Fluid dynamics

editIn fluid dynamics, complex functions are used to describe potential flow in two dimensions.

Quantum mechanics

editThe complex number field is intrinsic to the mathematical formulations of quantum mechanics, where complex Hilbert spaces provide the context for one such formulation that is convenient and perhaps most standard. The original foundation formulas of quantum mechanics – the Schrödinger equation and Heisenberg's matrix mechanics – make use of complex numbers.

Relativity

editIn special and general relativity, some formulas for the metric on spacetime become simpler if one takes the time component of the spacetime continuum to be imaginary. (This approach is no longer standard in classical relativity, but is used in an essential way in quantum field theory.) Complex numbers are essential to spinors, which are a generalization of the tensors used in relativity.

Characterizations, generalizations and related notions

editAlgebraic characterization

editThe field has the following three properties:

- First, it has characteristic 0. This means that 1 + 1 + ⋯ + 1 ≠ 0 for any number of summands (all of which equal one).

- Second, its transcendence degree over , the prime field of is the cardinality of the continuum.

- Third, it is algebraically closed (see above).

It can be shown that any field having these properties is isomorphic (as a field) to For example, the algebraic closure of the field of the p-adic number also satisfies these three properties, so these two fields are isomorphic (as fields, but not as topological fields).[59] Also, is isomorphic to the field of complex Puiseux series. However, specifying an isomorphism requires the axiom of choice. Another consequence of this algebraic characterization is that contains many proper subfields that are isomorphic to .

Characterization as a topological field

editThe preceding characterization of describes only the algebraic aspects of That is to say, the properties of nearness and continuity, which matter in areas such as analysis and topology, are not dealt with. The following description of as a topological field (that is, a field that is equipped with a topology, which allows the notion of convergence) does take into account the topological properties. contains a subset P (namely the set of positive real numbers) of nonzero elements satisfying the following three conditions:

- P is closed under addition, multiplication and taking inverses.

- If x and y are distinct elements of P, then either x − y or y − x is in P.

- If S is any nonempty subset of P, then S + P = x + P for some x in

Moreover, has a nontrivial involutive automorphism x ↦ x* (namely the complex conjugation), such that x x* is in P for any nonzero x in

Any field F with these properties can be endowed with a topology by taking the sets B(x, p) = { y | p − (y − x)(y − x)* ∈ P } as a base, where x ranges over the field and p ranges over P. With this topology F is isomorphic as a topological field to

The only connected locally compact topological fields are and This gives another characterization of as a topological field, because can be distinguished from because the nonzero complex numbers are connected, while the nonzero real numbers are not.[60]

Other number systems

edit| rational numbers | real numbers | complex numbers | quaternions | octonions | sedenions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| complete | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| dimension as an -vector space | [does not apply] | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 16 |

| ordered | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| multiplication commutative ( ) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| multiplication associative ( ) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| normed division algebra (over ) | [does not apply] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

The process of extending the field of reals to is an instance of the Cayley–Dickson construction. Applying this construction iteratively to then yields the quaternions, the octonions,[61] the sedenions, and the trigintaduonions. This construction turns out to diminish the structural properties of the involved number systems.

Unlike the reals, is not an ordered field, that is to say, it is not possible to define a relation z1 < z2 that is compatible with the addition and multiplication. In fact, in any ordered field, the square of any element is necessarily positive, so i2 = −1 precludes the existence of an ordering on [62] Passing from to the quaternions loses commutativity, while the octonions (additionally to not being commutative) fail to be associative. The reals, complex numbers, quaternions and octonions are all normed division algebras over . By Hurwitz's theorem they are the only ones; the sedenions, the next step in the Cayley–Dickson construction, fail to have this structure.

The Cayley–Dickson construction is closely related to the regular representation of thought of as an -algebra (an -vector space with a multiplication), with respect to the basis (1, i). This means the following: the -linear map for some fixed complex number w can be represented by a 2 × 2 matrix (once a basis has been chosen). With respect to the basis (1, i), this matrix is that is, the one mentioned in the section on matrix representation of complex numbers above. While this is a linear representation of in the 2 × 2 real matrices, it is not the only one. Any matrix has the property that its square is the negative of the identity matrix: J2 = −I. Then is also isomorphic to the field and gives an alternative complex structure on This is generalized by the notion of a linear complex structure.

Hypercomplex numbers also generalize and For example, this notion contains the split-complex numbers, which are elements of the ring (as opposed to for complex numbers). In this ring, the equation a2 = 1 has four solutions.

The field is the completion of the field of rational numbers, with respect to the usual absolute value metric. Other choices of metrics on lead to the fields of p-adic numbers (for any prime number p), which are thereby analogous to . There are no other nontrivial ways of completing than and by Ostrowski's theorem. The algebraic closures of still carry a norm, but (unlike ) are not complete with respect to it. The completion of turns out to be algebraically closed. By analogy, the field is called p-adic complex numbers.

The fields and their finite field extensions, including are called local fields.

See also

edit- Analytic continuation

- Circular motion using complex numbers

- Complex-base system

- Complex coordinate space

- Complex geometry

- Geometry of numbers

- Dual-complex number

- Eisenstein integer

- Geometric algebra (which includes the complex plane as the 2-dimensional spinor subspace )

- Unit complex number

Notes

edit- ^ Solomentsev 2001: "The plane whose points are identified with the elements of is called the complex plane ... The complete geometric interpretation of complex numbers and operations on them appeared first in the work of C. Wessel (1799). The geometric representation of complex numbers, sometimes called the 'Argand diagram', came into use after the publication in 1806 and 1814 of papers by J.R. Argand, who rediscovered, largely independently, the findings of Wessel".

- ^ In the literature the imaginary unit often precedes the radical sign, even when preceded itself by an integer.[26]

- ^ It has been proved that imaginary numbers necessarily appear in the cubic formula when the equation has three real, different roots by Pierre Laurent Wantzel in 1843, Vincenzo Mollame in 1890, Otto Hölder in 1891, and Adolf Kneser in 1892. Paolo Ruffini also provided an incomplete proof in 1799.——S. Confalonieri (2015)[28]

- ^ Argand 1814, p. 204 defines the modulus of a complex number but he doesn't name it:

"Dans ce qui suit, les accens, indifféremment placés, seront employés pour indiquer la grandeur absolue des quantités qu'ils affectent; ainsi, si , et étant réels, on devra entendre que ou ."

[In what follows, accent marks, wherever they're placed, will be used to indicate the absolute size of the quantities to which they're assigned; thus if , and being real, one should understand that or .]

Argand 1814, p. 208 defines and names the module and the direction factor of a complex number: "... pourrait être appelé le module de , et représenterait la grandeur absolue de la ligne , tandis que l'autre facteur, dont le module est l'unité, en représenterait la direction."

[... could be called the module of and would represent the absolute size of the line (Argand represented complex numbers as vectors.) whereas the other factor [namely, ], whose module is unity [1], would represent its direction.] - ^ Gauss writes:[50] "Quemadmodum scilicet arithmetica sublimior in quaestionibus hactenus pertractatis inter solos numeros integros reales versatur, ita theoremata circa residua biquadratica tunc tantum in summa simplicitate ac genuina venustate resplendent, quando campus arithmeticae ad quantitates imaginarias extenditur, ita ut absque restrictione ipsius obiectum constituant numeri formae a + bi, denotantibus i, pro more quantitatem imaginariam , atque a, b indefinite omnes numeros reales integros inter - et + ." [Of course just as the higher arithmetic has been investigated so far in problems only among real integer numbers, so theorems regarding biquadratic residues then shine in greatest simplicity and genuine beauty, when the field of arithmetic is extended to imaginary quantities, so that, without restrictions on it, numbers of the form a + bi — i denoting by convention the imaginary quantity , and the variables a, b [denoting] all real integer numbers between and — constitute an object.]

- ^ Gauss:[51] "Tales numeros vocabimus numeros integros complexos, ita quidem, ut reales complexis non opponantur, sed tamquam species sub his contineri censeantur." [We will call such numbers [namely, numbers of the form a + bi ] "complex integer numbers", so that real [numbers] are regarded not as the opposite of complex [numbers] but [as] a type [of number that] is, so to speak, contained within them.]

- ^ Gauss:[52] "Productum numeri complexi per numerum ipsi conjunctum utriusque normam vocamus. Pro norma itaque numeri realis, ipsius quadratum habendum est." [We call a "norm" the product of a complex number [for example, a + ib ] with its conjugate [a - ib ]. Therefore the square of a real number should be regarded as its norm.]

- ^ However for another inverse function of the complex exponential function (and not the above defined principal value), the branch cut could be taken at any other ray thru the origin.

References

edit- ^ For an extensive account of the history of "imaginary" numbers, from initial skepticism to ultimate acceptance, see Bourbaki, Nicolas (1998). "Foundations of Mathematics § Logic: Set theory". Elements of the History of Mathematics. Springer. pp. 18–24.

- ^ "Complex numbers, as much as reals, and perhaps even more, find a unity with nature that is truly remarkable. It is as though Nature herself is as impressed by the scope and consistency of the complex-number system as we are ourselves, and has entrusted to these numbers the precise operations of her world at its minutest scales.", Penrose 2005, pp.72–73.

- ^ Axler, Sheldon (2010). College algebra. Wiley. p. 262. ISBN 9780470470770.

- ^ Spiegel, M.R.; Lipschutz, S.; Schiller, J.J.; Spellman, D. (14 April 2009). Complex Variables. Schaum's Outline Series (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-161569-3.

- ^ Aufmann, Barker & Nation 2007, p. 66, Chapter P

- ^ Pedoe, Dan (1988). Geometry: A comprehensive course. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65812-4.

- ^ a b Weisstein, Eric W. "Complex Number". mathworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ Campbell, George Ashley (April 1911). "Cisoidal oscillations" (PDF). Proceedings of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. XXX (1–6). American Institute of Electrical Engineers: 789–824 [Fig. 13 on p. 810]. doi:10.1109/PAIEE.1911.6659711. S2CID 51647814. Retrieved 24 June 2023. p. 789:

The use of i (or Greek ı) for the imaginary symbol is nearly universal in mathematical work, which is a very strong reason for retaining it in the applications of mathematics in electrical engineering. Aside, however, from the matter of established conventions and facility of reference to mathematical literature, the substitution of the symbol j is objectionable because of the vector terminology with which it has become associated in engineering literature, and also because of the confusion resulting from the divided practice of engineering writers, some using j for +i and others using j for −i.

- ^ Brown, James Ward; Churchill, Ruel V. (1996). Complex variables and applications (6 ed.). New York, USA: McGraw-Hill. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-07-912147-9. p. 2:

In electrical engineering, the letter j is used instead of i.

- ^ Apostol 1981, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Apostol 1981, pp. 15–16

- ^ Apostol 1981, p. 18.

- ^ William Ford (2014). Numerical Linear Algebra with Applications: Using MATLAB and Octave (reprinted ed.). Academic Press. p. 570. ISBN 978-0-12-394784-0. Extract of page 570

- ^ Dennis Zill; Jacqueline Dewar (2011). Precalculus with Calculus Previews: Expanded Volume (revised ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7637-6631-3. Extract of page 37

- ^ Other authors, including Ebbinghaus et al. 1991, §6.1, chose the argument to be in the interval .

- ^ Kasana, H.S. (2005). "Chapter 1". Complex Variables: Theory And Applications (2nd ed.). PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 978-81-203-2641-5.

- ^ Nilsson, James William; Riedel, Susan A. (2008). "Chapter 9". Electric circuits (8th ed.). Prentice Hall. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-13-198925-2.

- ^ Lloyd James Peter Kilford (2015). Modular Forms: A Classical And Computational Introduction (2nd ed.). World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-78326-547-3. Extract of page 112

- ^ Bourbaki 1998, §VIII.1

- ^ Kline, Morris. A history of mathematical thought, volume 1. p. 253.

- ^ Jurij., Kovič. Tristan Needham, Visual Complex Analysis, Oxford University Press Inc., New York, 1998, 592 strani. OCLC 1080410598.

- ^ O'Connor and Robertson (2016), "Girolamo Cardano."

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. An Imaginary Tale: The Story of √−1. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998.

- ^ Katz, Victor J. (2004). "9.1.4". A History of Mathematics, Brief Version. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-16193-2.

- ^ Hamilton, Wm. (1844). "On a new species of imaginary quantities connected with a theory of quaternions". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. 2: 424–434.

- ^ Cynthia Y. Young (2017). Trigonometry (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 406. ISBN 978-1-119-44520-3. Extract of page 406

- ^ Nahin, Paul J. (2007). An Imaginary Tale: The Story of √−1. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12798-9. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ a b Confalonieri, Sara (2015). The Unattainable Attempt to Avoid the Casus Irreducibilis for Cubic Equations: Gerolamo Cardano's De Regula Aliza. Springer. pp. 15–16 (note 26). ISBN 978-3658092757.

- ^ Descartes, René (1954) [1637]. La Géométrie | The Geometry of René Descartes with a facsimile of the first edition. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-60068-0. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Joseph Mazur (2016). Enlightening Symbols: A Short History of Mathematical Notation and Its Hidden Powers (reprinted ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-0-691-17337-5. Extract of page 138

- ^ Bryan Bunch (2012). Mathematical Fallacies and Paradoxes (reprinted, revised ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-486-13793-3. Extract of page 32

- ^ Euler, Leonard (1748). Introductio in Analysin Infinitorum [Introduction to the Analysis of the Infinite] (in Latin). Vol. 1. Lucerne, Switzerland: Marc Michel Bosquet & Co. p. 104.

- ^ Wessel, Caspar (1799). "Om Directionens analytiske Betegning, et Forsog, anvendt fornemmelig til plane og sphæriske Polygoners Oplosning" [On the analytic representation of direction, an effort applied in particular to the determination of plane and spherical polygons]. Nye Samling af det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskabs Skrifter [New Collection of the Writings of the Royal Danish Science Society] (in Danish). 5: 469–518.

- ^ Wallis, John (1685). A Treatise of Algebra, Both Historical and Practical ... London, England: printed by John Playford, for Richard Davis. pp. 264–273.

- ^ Argand (1806). Essai sur une manière de représenter les quantités imaginaires dans les constructions géométriques [Essay on a way to represent complex quantities by geometric constructions] (in French). Paris, France: Madame Veuve Blanc.

- ^ Gauss, Carl Friedrich (1799) "Demonstratio nova theorematis omnem functionem algebraicam rationalem integram unius variabilis in factores reales primi vel secundi gradus resolvi posse." [New proof of the theorem that any rational integral algebraic function of a single variable can be resolved into real factors of the first or second degree.] Ph.D. thesis, University of Helmstedt, (Germany). (in Latin)

- ^ Ewald, William B. (1996). From Kant to Hilbert: A Source Book in the Foundations of Mathematics. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. p. 313. ISBN 9780198505358. Retrieved 18 March 2020.

- ^ Gauss 1831.

- ^ "Adrien Quentin Buée (1745–1845): MacTutor".

- ^ Buée (1806). "Mémoire sur les quantités imaginaires" [Memoir on imaginary quantities]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London (in French). 96: 23–88. doi:10.1098/rstl.1806.0003. S2CID 110394048.

- ^ Mourey, C.V. (1861). La vraies théore des quantités négatives et des quantités prétendues imaginaires [The true theory of negative quantities and of alleged imaginary quantities] (in French). Paris, France: Mallet-Bachelier. 1861 reprint of 1828 original.

- ^ Warren, John (1828). A Treatise on the Geometrical Representation of the Square Roots of Negative Quantities. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Warren, John (1829). "Consideration of the objections raised against the geometrical representation of the square roots of negative quantities". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 119: 241–254. doi:10.1098/rstl.1829.0022. S2CID 186211638.

- ^ Warren, John (1829). "On the geometrical representation of the powers of quantities, whose indices involve the square roots of negative numbers". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 119: 339–359. doi:10.1098/rstl.1829.0031. S2CID 125699726.

- ^ Français, J.F. (1813). "Nouveaux principes de géométrie de position, et interprétation géométrique des symboles imaginaires" [New principles of the geometry of position, and geometric interpretation of complex [number] symbols]. Annales des mathématiques pures et appliquées (in French). 4: 61–71.

- ^ Caparrini, Sandro (2000). "On the Common Origin of Some of the Works on the Geometrical Interpretation of Complex Numbers". In Kim Williams (ed.). Two Cultures. Birkhäuser. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-7643-7186-9.

- ^ Hardy, G.H.; Wright, E.M. (2000) [1938]. An Introduction to the Theory of Numbers. OUP Oxford. p. 189 (fourth edition). ISBN 978-0-19-921986-5.

- ^ Jeff Miller (21 September 1999). "MODULUS". Earliest Known Uses of Some of the Words of Mathematics (M). Archived from the original on 3 October 1999.

- ^ Cauchy, Augustin-Louis (1821). Cours d'analyse de l'École royale polytechnique (in French). Vol. 1. Paris, France: L'Imprimerie Royale. p. 183.

- ^ Gauss 1831, p. 96

- ^ Gauss 1831, p. 96

- ^ Gauss 1831, p. 98

- ^ Hankel, Hermann (1867). Vorlesungen über die complexen Zahlen und ihre Functionen [Lectures About the Complex Numbers and Their Functions] (in German). Vol. 1. Leipzig, [Germany]: Leopold Voss. p. 71. From p. 71: "Wir werden den Factor (cos φ + i sin φ) haüfig den Richtungscoefficienten nennen." (We will often call the factor (cos φ + i sin φ) the "coefficient of direction".)

- ^ Bourbaki 1998, §VIII.1

- ^ Lester, J.A. (1994). "Triangles I: Shapes". Aequationes Mathematicae. 52: 30–54. doi:10.1007/BF01818325. S2CID 121095307.

- ^ Kalman, Dan (2008a). "An Elementary Proof of Marden's Theorem". American Mathematical Monthly. 115 (4): 330–38. doi:10.1080/00029890.2008.11920532. ISSN 0002-9890. S2CID 13222698. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Kalman, Dan (2008b). "The Most Marvelous Theorem in Mathematics". Journal of Online Mathematics and Its Applications. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ Grant, I.S.; Phillips, W.R. (2008). Electromagnetism (2 ed.). Manchester Physics Series. ISBN 978-0-471-92712-9.

- ^ Marker, David (1996). "Introduction to the Model Theory of Fields". In Marker, D.; Messmer, M.; Pillay, A. (eds.). Model theory of fields. Lecture Notes in Logic. Vol. 5. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. pp. 1–37. ISBN 978-3-540-60741-0. MR 1477154.

- ^ Bourbaki 1998, §VIII.4.

- ^ McCrimmon, Kevin (2004). A Taste of Jordan Algebras. Universitext. Springer. p. 64. ISBN 0-387-95447-3. MR2014924

- ^ Apostol 1981, p. 25.

- Ahlfors, Lars (1979). Complex analysis (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-000657-7.

- Andreescu, Titu; Andrica, Dorin (2014), Complex Numbers from A to ... Z (Second ed.), New York: Springer, doi:10.1007/978-0-8176-8415-0, ISBN 978-0-8176-8414-3

- Apostol, Tom (1981). Mathematical analysis. Addison-Wesley.

- Aufmann, Richard N.; Barker, Vernon C.; Nation, Richard D. (2007). College Algebra and Trigonometry (6 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-618-82515-8.

- Conway, John B. (1986). Functions of One Complex Variable I. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-90328-6.

- Derbyshire, John (2006). Unknown Quantity: A real and imaginary history of algebra. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 978-0-309-09657-7.

- Joshi, Kapil D. (1989). Foundations of Discrete Mathematics. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-21152-6.

- Needham, Tristan (1997). Visual Complex Analysis. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-853447-1.

- Pedoe, Dan (1988). Geometry: A comprehensive course. Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-65812-4.

- Penrose, Roger (2005). The Road to Reality: A complete guide to the laws of the universe. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-679-45443-4.

- Press, W.H.; Teukolsky, S.A.; Vetterling, W.T.; Flannery, B.P. (2007). "Section 5.5 Complex Arithmetic". Numerical Recipes: The art of scientific computing (3rd ed.). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8. Archived from the original on 13 March 2020. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001) [1994], "Complex number", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press

Historical references

edit- Argand (1814). "Reflexions sur la nouvelle théorie des imaginaires, suives d'une application à la demonstration d'un theorème d'analise" [Reflections on the new theory of complex numbers, followed by an application to the proof of a theorem of analysis]. Annales de mathématiques pures et appliquées (in French). 5: 197–209.

- Bourbaki, Nicolas (1998). "Foundations of mathematics § logic: set theory". Elements of the history of mathematics. Springer.

- Burton, David M. (1995). The History of Mathematics (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-009465-9.

- Gauss, C. F. (1831). "Theoria residuorum biquadraticorum. Commentatio secunda" [Theory of biquadratic residues. Second memoir.]. Commentationes Societatis Regiae Scientiarum Gottingensis Recentiores (in Latin). 7: 89–148.

- Katz, Victor J. (2004). A History of Mathematics, Brief Version. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-16193-2.

- Nahin, Paul J. (1998). An Imaginary Tale: The Story of . Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02795-1. — A gentle introduction to the history of complex numbers and the beginnings of complex analysis.

- Ebbinghaus, H. D.; Hermes, H.; Hirzebruch, F.; Koecher, M.; Mainzer, K.; Neukirch, J.; Prestel, A.; Remmert, R. (1991). Numbers (hardcover ed.). Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-97497-2. — An advanced perspective on the historical development of the concept of number.