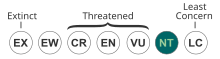

The cocha antshrike (Thamnophilus praecox) is a Near Threatened species of bird in subfamily Thamnophilinae of family Thamnophilidae, the "typical antbirds".[2] It is found in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.[3]

| Cocha antshrike | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female | |

| |

| Male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thamnophilidae |

| Genus: | Thamnophilus |

| Species: | T. praecox

|

| Binomial name | |

| Thamnophilus praecox Zimmer, 1937

| |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics

editThe cocha antshrike is monotypic.[2] It and the black antshrike (T. nigriceps) are sister species.[4]

Description

editThe cocha antshrike is about 16 cm (6.3 in) long. Members of genus Thamnophilus are largish members of the antbird family; all have stout bills with a hook like those of true shrikes. This species exhibits sexual dimorphism. Adult males are entirely black except that their underwing coverts are white, a feature that is seldom visible in the field. Adult females have a black head, throat, and upper breast. Some individuals have faint white streaks on their throat. The rest of their body, their wings, and their tail are cinnamon-rufous; their underparts are slightly paler than their back.[5][6][7]

Distribution and habitat

editThe cocha antshrike was long thought to be endemic to northeastern Ecuador, where it occurs locally along the Rio Napo and its tributaries.[5][6] The International Ornithological Committee lists it that way.[2] However, by 2021 the South American Classification Committee of the American Ornithological Society (SACC) had recognized that it also occurred further upstream in that river system in extreme south-central Colombia.[8] In March 2024 the SACC recognized documented records from Peru.[3] In late 2023 the Clements taxonomy revised its range statement to read "northeastern Ecuador (locally along the Río Napo and its tributaries in eastern Napo and eastern Sucumbíos) and adjacent Colombia (locally in Putumayo and southwestern Caqueta); disjunctly in northern Peru (on the Canal de Puinahua, in south-central Loreto)".[9]

The cocha antshrike is found along blackwater rivers, usually small ones, in seasonally flooded várzea forest. It favors dense thickets and tangles. In elevation it occurs between about 160 and 300 m (500 and 1,000 ft) above sea level.[1][5][6]

Behavior

editMovement

editThe cocha antshrike is presumed to be a year-round resident throughout its range.[5]

Feeding

editThe cocha antshrike's diet is not known but is assumed to be insects and other arthropods. It usually forages singly or in pairs and seldom joins mixed-species feeding flocks. It forages in dense vegetation where it hops among branches to glean prey.[5][6][7]

Breeding

editNothing is known about the cocha antshrike's breeding biology.[5]

Vocalization

editThe cocha antshrike's song is "a hollow, evenly paced ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ko"; it sometimes follows it with a shorter and higher pitched version of the song. Its calls include "a mellow 'pwow-pwow' and a more trilled 'krrrrrr' ".[6]

Status

editThe IUCN has assessed the cocha antshrike as Near Threatened. It has a very limited range and its estimated population of 8000 mature individuals is believed to be decreasing. "Deforestation is extensive in the western part of the range (particularly in Ecuador) due to the expansion of oil exploration...[v]ast areas of pristine habitat however remain in the eastern part of the range."[1] Though the cocha antshrike was described for science in 1937, it was known only from the holotype until 1990, when it was rediscovered near where that specimen had been collected. It is considered fairly common but local in Ecuador and Peru.[5]

References

edit- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2023). "Cocha Antshrike Thamnophilus praecox". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2023: e.T22701299A223718838. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2023-1.RLTS.T22701299A223718838.en. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2024). "Antbirds". IOC World Bird List. v 14.1. Retrieved 4 January 2024.

- ^ a b Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 4 March 2024. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCCountryLists.htm retrieved March 5, 2024

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 4 March 2024. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithological Society. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved March 5, 2024

- ^ a b c d e f g Zimmer, K. and M.L. Isler (2020). Cocha Antshrike (Thamnophilus praecox), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.cocant1.01 retrieved March 21, 2024

- ^ a b c d e Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 393–394. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b Schulenberg, T.S., D.F. Stotz, D.F. Lane, J.P. O’Neill, and T.A. Parker III. 2010. Birds of Peru. Revised and updated edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey plate 159

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 19 January 2021. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. retrieved January 20, 2021

- ^ Clements, J. F., P.C. Rasmussen, T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, A. Spencer, S. M. Billerman, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2023. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2023. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ retrieved October 28, 2023