The City Palace, Jaipur is a royal residence and former administrative headquarters of the rulers of the Jaipur State in Jaipur, Rajasthan.[1] Construction started soon after the establishment of the city of Jaipur under the reign of Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II, who moved his court to Jaipur from Amber, in 1727.[2] Jaipur remained the capital of the kingdom until 1949—when it became the capital of the present-day Indian state of Rajasthan—with the City Palace functioning as the ceremonial and administrative seat of the Maharaja of Jaipur.[2] The construction of the Palace was completed in 1732 and it was also the location of religious and cultural events, as well as a patron of arts, commerce, and industry. It was constructed according to the rules of vastushastra, combining elements of Mughal and Rajput architectural styles.[1] It now houses the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum, and continues to be the home of the Jaipur royal family. The royal family has around 500 personal servants.[citation needed] The palace complex has several buildings, various courtyards, galleries, restaurants, and offices of the Museum Trust.The MSMS II Museum Trust is headed by chairperson Rajamata Padmini Devi of Jaipur (from Sirmour in Himachal Pradesh).[3] Princess Diya Kumari runs the Museum Trust, as its secretary and trustee. She also manages The Palace School and Maharaja Sawai Bhawani Singh School in Jaipur. She founded and runs the Princess Diya Kumari Foundation to empower underprivileged and underemployed women of Rajasthan. She is also an entrepreneur. In 2013, she was elected as Member of the Legislative Assembly of Rajasthan from the constituency of Sawai Madhopur.[3]

| City Palace of Jaipur | |

|---|---|

Front elevation of City Palace | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Combination of Rajput, Mughal and European influence |

| Location | Jaipur, Rajasthan |

| Country | India |

| Coordinates | 26°55′33″N 75°49′25″E / 26.9257°N 75.8236°E |

| Construction started | 1729 |

| Completed | 1732 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Vidyadar Bhattacharya[1] |

| Main contractor | Jai Singh II |

History

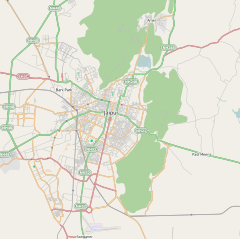

editThe palace complex lies in the heart of Jaipur city, to the northeast of the very centre, located at 26°55′32″N 75°49′25″E / 26.9255°N 75.8236°E. The site for the palace was located on the site of a royal hunting lodge on a plain land encircled by a rocky hill range, five miles south of Amber. The history of the city palace is closely linked with the history of Jaipur city And its rulers, starting with Maharaja Sawai Jai Singh II who ruled from 1699 to 1744. He is credited with initiating construction of the city complex by building the outer wall of the complex spreading over many acres. Initially, he ruled from his capital at Amber, which lies at a distance of 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) from Jaipur. He shifted his capital from Amber to Jaipur in 1727 because of an increase in population and increasing water shortage. He planned Jaipur city in six blocks separated by broad avenues, on the classical basis of principals of Vastushastra and another similar classical treatise under the architectural guidance of Vidyadar Bhattacharya, a Bengali architect from Naihati of present-day West Bengal who was initially an accounts-clerk in the Amber treasury and later promoted to the office of Chief Architect by the King.[4][5][6][7]

Following Jai Singh's death in 1744, there were internecine wars among the Rajput kings of the region but cordial relations were maintained with the British Raj. Maharaja Ram Singh sided with the British in the Sepoy Mutiny or Uprising of 1857 and established himself with the Imperial rulers. It is to his credit that the city of Jaipur including all of its monuments (including the City Palace) are stucco painted 'Pink' and since then the city has been called the "Pink City".The change in the colour scheme was as an honor of hospitality extended to the Prince of Wales (who later became King Edward VII) on his visit. This color scheme has since then become a trademark of the Jaipur city.[7]

Man Singh II, the adopted son of Maharaja Madho Singh II, was the last Maharaja of Jaipur to rule from the Chandra Mahal palace, in Jaipur. This palace, however, continued to be a residence of the royal family even after the Jaipur kingdom merged with the Indian Union in 1949 (after Indian independence in August 1947) along with other Rajput states of Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Bikaner. Jaipur became the capital of the Indian state of Rajasthan and Man Singh II had the distinction of becoming the Rajapramukh (present-day Governor of the state) for a time and later was the Ambassador of India to Spain.[7]

Architecture

editThe City Palace is in the central-northeast part of the Jaipur city, which is laid in a unique pattern with wide avenues. It is a unique and special complex of several courtyards, buildings, pavilions, gardens, and temples. The most prominent and most visited structures in the complex are the Chandra Mahal, Mubarak Mahal, Shri Govind Dev Temple, and the City Palace Museum.

Govind Dev Ji temple

editGovind Dev Ji temple, dedicated to the Hindu God Lord Krishna, is part of the City Palace complex. Govind Dev an important deity, featured in many paintings, and on a large pichchawi (painted backdrop) on display in the Painting and Photography gallery.

Entrance gates

editThe Udai Pol near Jaleb chowk, the Virendra Pol near Jantar Mantar, and the Tripolia (three pols or gates) are the three main entry gates of the City Palace. The Tripolia gate is reserved for the entry of the royal family into the palace. Common people and visitors can enter the place complex only through the Udai Pol and the Virendra Pol. The Udai Pol leads to the Sabha Niwas (the Diwan-e-Aam or hall of public audience) through a series of tight dog-leg turns. The Virendra Pol leads to the Mubarak Mahal courtyard, which in turn is connected to the Sarvato Bhadra (the Diwan-e-Khas) through the Rajendra Pol. The gateways were built at different times across the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries and are richly decorated in the contemporary architectural styles prevalent at the time.[8][9][10]

Sabha Niwas (Diwan-e-Aam)

editModeled on the lines of a Mughal hall of audience, the Diwan-e-Aam, the Sabha Niwas, is a hall of the public audience. It has multiple cusped arches supported by marble columns and a beautifully painted plaster ceiling. The jalis on the southern end of the hall would have been used by women to oversee the proceedings in the hall, and facilitated their involvement in the outside world, while following the purdah.

Sarvato Bhadra (Diwan-e-Khas)

editThe Sarvato Bhadra is a unique architectural feature. The unusual name refers to the building's form: a Sarvato Bhadra is a single-storeyed, square, open hall, with enclosed rooms at the four corners.[11] One use of the Sarvato Bhadra was as the Diwan-e-Khas, or the Hall of Private Audience, which meant the ruler could hold court with the officials and nobles of the kingdom in a more private, intimate space than the grand spaces of the Sabha Niwas in the next courtyard, which was open to more people. But it's also one of the most important ritual buildings in the complex, and continues to be so today, representing as it does, 'living heritage'. Because of its location between the public areas and the private residence, it has traditionally been used for important private functions like the coronation rituals of the Maharajas of Jaipur.

Today, it continues to be used for royal festivals and celebrations like Dusshera. During Gangaur and Teej, the image of the goddess is placed in her palanquin in the centre of the hall, before being carried in procession around the city. During the harvest festival of Makar Sankranti, paper kites belonging to Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II who lived almost 150 years ago are displayed in the centre, and the roof is used for flying kites. It is also used for more modern celebrations like parties and weddings.

There are two huge sterling silver vessels of 1.6 metres (5.2 ft) height and each with capacity of 4000 litres and weighing 340 kilograms (750 lb), on display here. They were made from 14,000 melted silver coins without soldering. They hold the Guinness World Record as the world's largest sterling silver vessels.[12] These vessels were specially commissioned by Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II to carry the water of the Ganges to drink on his trip to England in 1902 (for Edward VII's coronation). Hence, the vessels are named as Gangajalis (Ganges-water urns).[5][6][10][13][14]

Pritam Niwas Chowk

editIt is the inner courtyard, which provides access to the Chandra Mahal. Here, there are four small gates (known as Ridhi Sidhi Pol) that are adorned with themes representing the four seasons and Hindu gods. The gates are the Northeast Peacock Gate (with motifs of peacocks on the doorway) representing autumn and dedicated Lord Vishnu; the Southeast Lotus Gate (with continual flower and petal pattern) suggestive of summer season and dedicated to Lord Shiva-Parvati; the Northwest Green Gate, also called the Leheriya (meaning: "waves") gate, in green colour suggestive of spring and dedicated to Lord Ganesha, and lastly, the Southwest Rose Gate with repeated flower pattern representing winter season and dedicated to Goddess Devi.[13][15]

Chandra Mahal

editChandra Mahal is one of the oldest buildings in the City Palace complex. It has seven floors, a number considered auspicious by Rajput rulers. The first two floors consist of the Sukh Niwas (the house of pleasure), followed by the Shobha Niwas with coloured glasswork, then Chhavi Niwas with its blue and white decorations. The last two floors are the Shri Niwas, and Mukut Mandir which is literally the crowning pavilion of this palace. The Mukut Mandir, with a bangaldar roof, has the royal standard of Jaipur hoisted at all times, as well as a quarter flag (underscoring the Sawai in the title) when the Maharaja is in residence.[16]

There is an anecdote narrated about the 'one and quarter flag', which is the insignia flag of the Maharajas of Jaipur. Emperor Aurangzeb who attended the wedding of Jai Singh, shook hands with the young groom and wished him well on his marriage. On this occasion, Jai Singh made an irreverent remark to the Emperor stating that the way he had shaken hands with him made it incumbent on the Emperor to protect him (Jai Singh) and his kingdom. Aurangzeb, instead of responding in indignation at the quip, felt pleased and conferred on the young Jai Singh the title of 'Sawai', which means "one and a quarter". Since then the Maharajas have pre-fixed their names with this title. During residence there, they also fly a one and a quarter size flag atop their buildings and palaces.[7]

-

View of the Chandra Mahal from the Pritam Niwas courtyard

-

Closer view of the Jaipur flag on top of the Mukut Mandir

-

Chhavi Niwas, the blue room

-

Sobha Niwas, decorated with glassworks

-

Chandra Mahal in 1885 from the Jai Niwas garden

Mubarak Mahal

editThe Mubarak Mahal courtyard at the City Palace was fully developed as late as 1900, when the court architect of the time, Lala Chiman Lal, constructed the Mubarak Mahal in its centre. Chiman Lal, had worked with Samuel Swinton Jacob, the State's executive engineer, and also built the Rajendra Pol around the same time as the Mubarak Mahal, complementing it in style. The facade of the Mubarak Mahal has a hanging balcony and is identical on all four sides, the intricate carving in white (andhi marble) and beige stone giving it the illusion of delicate decoupage. The Mubarak Mahal was built for receiving foreign guests but it now houses the museum offices and a library on the first floor and the museum's Textile Gallery on the ground floor.[8][16]

The Clock Tower

editThe clock tower is a structure to the south of the Sabha Niwas. It is a sign of European influence in the Rajput court as the clock was installed in a pre-existing tower in 1873. The clock, purchased from Black and Murray & Co. of Calcutta, aimed to introduce a little Victorian efficiency and punctuality into court proceedings.[2]

Galleries of the museum

editSabha Niwas (Hall of Audience)

editThis is the main hall of audience. It is a large room with two thrones at the centre, a set of chairs around, as if in a durbar setting. On the walls of the halls are large format paintings of the Maharajas of Jaipur, a large picchwai (a backdrop for a shrine), large paintings depicting the colourful festival of holi, and a pair of paintings featuring spring and summer (possibly made in the Deccan). On display, you can also see military medals and polo trophies, marking the achievements of the rulers. The room is opulent in its decoration, with murals, and chandeliers. The current closed arches, on which the Holi paintings, and the Spring and Summer portrait hang, were closed in the recent times. Photos from the reign of Man Singh II, of the court in attendance, Lord and Lady Mountbatten's visit, line the corridor leading out to the Sarvato Bhadra courtyard.

Textile Gallery

editThis gallery is situated on the ground floor of the Mubarak Mahal. On display are various kinds of textiles and fabrics, including Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh I's atmasukha, Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh's wedding jama, and a set of robes (angarakhas) belonging to Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II. Not to be missed is the rare pashmina carpet, made in Lahore or Kashmir around 1650. This gallery also has on display the Polo outfit and cups belonging Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II and the billiards outfit of Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II.

Sileh Khana (Arms and Armour Gallery)

editThe Sileh khana showcases the many arms used by the Kachhwaha Rajputs of Jaipur and Amber. The collection features early 19th century swords with a variety of decorations on the handle as well as sword blade or Shamshir Shikargah. According to Robert Elgood, two of such pieces on display have chiselled animals down the length of the blade (a concept acquired from Europe that allows decoration to a greater effect) the blade has raised figures, buildings, animals and birds all highlighted in gold. There is true damascening in gold on the hilt as well as the blades. These swords were never used and purely made for decorative purposes. The hilts of the pieces displayed are of different styles and can be accurately dated to the workshop set up for Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II ( r. 1880 – 1922).[17]

Highlights of the collection are a tulwar owned by Maharaja Ram Singh Ji II (1835–80) (name inscribed on the blade) which had a blade length of 54 cm – bright steel, single-edged khanda blade with ricasso, shallow central fuller, and false edge. The blade is stamped at the forte with a Trishul and is heavier and shorter than normal indicating a special purpose. The gallery also showcases a tulwar which belonged to Maharaja Sawai Madho Singh II (1912). The tulwar's hilt has chequered grip and pommel steel inlaid with silver flowers.[17]

Additionally, a beautifully painted shield featuring the clan goddess, Shila Mata, and hunting scenes, belonged to Maharaja Sawai Pratap Singh, and is an exquisite object of the collection, and a must-see object. The case also has a child's turban in metal which mimics a fabric turban, and is a unique item.

The armour section showcases helmets – "Khud". One of them is a 16th-century watered steel helmet which is rare to find. The helmet has been added with a false damascened band of decoration in the latter years of Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II (19th century). Watered steel was extremely expensive and therefore used very sparingly.

Painting and photography gallery

editOne of the newest galleries at The Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum is the Painting and Photography Gallery, where paintings and photographs from eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Jaipur are showcased. This gallery highlights the ways in which traditional artistic practices were transformed by political and cultural changes, modern technologies, and new materials.[18]

Art historians have subdivided Rajput painting, a form of painting that developed in the sixteenth century, based on the kingdoms from within they emerged: Marwar, Mewar, and Dhundhar.[19] Jaipur, the capital of the kingdom of Dhundhar, developed its own unique style of painting. At the same time, artistic exchanges between the Mughal and Rajput courts led to the development of new hybrid painting styles that brought together regional Indian, Mughal, and Persian traditions.[20] This was especially prevalent within the courts of kingdoms that were closely allied with the Mughal imperial court, such as Amber and Jaipur.

Currently, there are approximately 3,000 paintings housed in the MSMS II Museum, not including the paintings and manuscripts in the private collection of the royal family of Jaipur and in the kapad-dwara.[21] These include original Mughal and Deccani paintings, Jaipur copies of Mughal paintings, paintings from other Rajput kingdoms, religious and secular paintings, illustrated manuscripts, small- and large-scale portraits, nature studies, paper-cut collages, and other miscellaneous subjects.[21] Many of these are displayed in the Painting and Photography gallery. One of the most striking paintings in the collection is the artist Sahibram's large-scale composition of the Raas-lila. The painting is based on a re-enactment at the court, in which only women performed, even for the role of Krishna[22]

The photography collection at the Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II Museum consists of approximately 6,050 photographic prints, 1,941 glass plate negatives and photography equipment. This collection ranges from the 1860s to the 1950s and is unique due to its association with Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II, who was not only a collector and patron, but also a practitioner of photography.[23]

The photographic prints in the collection are mainly albumen and silver gelatin prints, on both printed and developed out paper. They consist of portraits, landscapes and architectural images and views of the Indian subcontinent by established photographers or studios such as Lala Deen Dayal, Jonston & Hoffman and Bourne & Shepherd.[23]

The glass plate negatives are primarily the work of Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II or his studio – the tasveerkhana – and are wet collodion plates, which was the dominant technology in use from the 1850s–1880s. The bulk of the negatives in the collection are portraits, but they also include numerous landscapes of Jaipur and Amber and art objects such as paintings and sword hilts. The most distinctive part of the collection is the set of wet plate negatives that documents the zenana women, offering us a unique insight into the microcosm of the zenana.[23]

The photographic equipment in the collection belonged to Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II and it appears to date from the 1860s. It includes the camera equipment and assorted accessories for practicing the wet plate collodion photography process.[23]

Museum Administration

Rima Hooja,[24] the well known archaeologist and historian, and author of several books such as A history of Rajasthan, Maharana Pratap- The invincible warrior, Rajasthan, The Ahar Culture and others is the Consultant Director of Maharaja Sawai Man Singh-II Museum,City Palace.

Entry timings

edit9.30 AM to 5.00 PM (Day visit)

7.00 PM to 10.00 PM (Night visit)[25]

Transport gallery

editThis gallery features pre-motorised transport like buggies, palkis, miyana, raths, camel saddles, etc. It is currently[when?] closed for renovation.

Gallery

edit-

Riddhi Siddhi Pol from Diwan-i-Khas

-

Clock Tower City Palace

-

Keeper at Rajendra Pol

-

Arches and columns on Elevation

-

Courtyard

-

Peacock Gate

-

Diwan-i Khas, "Hall of private audiences"

-

Guards around Diwan-i Khas

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Talwar, Shikha (15 February 2021). "35 inside pictures of the royal City Palace of Jaipur, the luxurious home of Maharaja Padmanabh Singh & family". GQ India. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Sachdev, Vibhuti (2008). Jaipur City Palace. Tillotson, G. H. R. (Giles Henry Rupert), 1960–, Chowdhury, Priyanka., Chowdhary, Eman. New Delhi: Lustre Press, Roli Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-8174365699. OCLC 276406345.

- ^ a b "The Royal Family: Present – Royal Jaipur- Explore the Royal Landmarks in Jaipur". Archived from the original on 27 September 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "City Palace Jaipur". Archived from the original on 10 January 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ a b "City Palace Jaipur". Archived from the original on 8 June 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ a b c d Brown p.149

- ^ a b Vibhuti Sachdev, Giles Tillotson (2008). Jaipur City Palace. Lustre Press, Roli Books. ISBN 978-81-7436-569-9.

- ^ Brown p.163

- ^ a b Bindolass, Joe; Sarina Singh (2007). India. Lonely Planet. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

City Palace, Jaipur.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Sachdev, Vibhuti (2008). Jaipur City Palace. Tillotson, G. H. R. (Giles Henry Rupert), 1960–, Chowdhury, Priyanka., Chowdhary, Eman. New Delhi: Lustre Press, Roli Books. ISBN 978-8174365699. OCLC 276406345.

- ^ "City Palace". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 11 December 2009.

- ^ a b Brown p.156

- ^ Matane, Paulias; M. L. Ahuja (2004). India: a splendour in cultural diversity. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 55–56. ISBN 81-261-1837-7. Archived from the original on 1 January 2024. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Jaipur the Pink City". Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Jaipur: History and Architecture | Sahapedia". www.sahapedia.org. Archived from the original on 28 August 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ a b Elgood, Robert (2015). Arms & armour at the Jaipur court : the royal collection. Niyogi Books. ISBN 9789383098774. OCLC 911067516.

- ^ Museum., Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II (2016). Painting & photography at the Jaipur court. Niyogi Books. ISBN 978-9385285240.

- ^ Four centuries of Rajput painting : Mewar, Marwar, and Dhundhar Indian miniatures from the collection of Isabella and Vicky Ducrot (1st ed.). Skira. 2009. ISBN 978-8857200187.

- ^ Mughal and Rajput painting. Cambridge University Press. 24 September 1992. ISBN 0521400279.

- ^ a b Museum., Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II (2016). Painting & photography at the Jaipur court. Niyogi Books. p. 12. ISBN 978-9385285240.

- ^ Museum., Maharaja Sawai Man Singh II (2016). Painting & photography at the Jaipur court. p. 101. ISBN 978-9385285240.

- ^ a b c d Mrinalini Venkateswaran, Giles Tillotson (2016). Painting & Painting Photography. ISBN 978-93-85285-24-0.

- ^ Khan, Murtaza Ali (14 March 2022). "It's exciting to be back at JLF: Museum Director Rima Hooja". National Herald. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "City Palace Jaipur". Exploremania.in. 17 January 2022. Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

References

edit- Bindolass, Joe; Sarina Singh (2007). India. Lonely Planet. pp. 1236. ISBN 978-1-74104-308-2.

City Palace, Jaipur.

- Brown, Lindsay; Amelia Thomas (2008). Rajasthan, Delhi and Agra. Lonely Planet. p. 420. ISBN 978-1-74104-690-8.

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Eastern and Southern Asia. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1584. ISBN 978-0-7614-7631-3.

- Matane, Paulias; M. L. Ahuja (2004). India: a splendour in cultural diversity. Anmol Publications Pvt. Ltd. p. 228. ISBN 81-261-1837-7.

Further reading

edit- Sachdev, Vibhuti; Tillotson, Giles Henry Rupert (2002). Building Jaipur: The Making of an Indian City. Reaktion Books, London. ISBN 1-86189-137-7.

External links

editMedia related to City Palace (Jaipur) at Wikimedia Commons