Chuanqi is a form of fictional short story or novella in Classical Chinese first formed in the Tang dynasty. The term often refers specifically to fictions written in the Tang dynasty, in which case the fictions are also called Tang chuanqi or chuanqi wen. Chuanqi originated from the zhiguai xiaoshuo of the Six Dynasties, was first formed in Early Tang dynasty, became popular in Middle Tang and dwindled in the Song dynasty. Chuanqi has four main themes: love, gods and demons, xiayi (heroes and knights-errant) and history.

| Chuanqi | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 傳奇 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 传奇 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | transmission [of the] strange | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Well-known works of chuanqi include Youxian ku by Zhang Zhuo, "The World Inside a Pillow" and "Renshi zhuan" ("The Tale of Miss Ren" or "The Story of Lady Ren") by Shen Jiji, Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen, The Tale of Huo Xiaoyu by Jiang Fang, The Tale of Li Wa by Bai Xingjian, "The Governor of Nanke" by Li Gongzuo, "The Tale of Hongxian" by Yuan Jiao, "Du Zichun" by Niu Sengru, "Tale of the Transcendent Marriage of Dongting Lake" by Li Chaowei, "Nie Yinniang" by Pei Xing, Chang hen ge zhuan by Chen Hong, and The Tale of the Curly-Bearded Guest by Du Guangting. Unlike general biji xiaoshuo and zhiguai xiaoshuo, most chuanqi stories have a complicated plot with twists and detailed descriptions and are meaningful literary creations instead of mere recordings of factual events.[1]: 230 They are some of the earliest Chinese literature written in the form of short and medium-length stories and have provided valuable inspiration plot-wise and in other ways for fiction and drama in later eras. Many were preserved in the 10th-century anthology, Taiping Guangji (Extensive Records of the Taiping Era).[2]

Definition

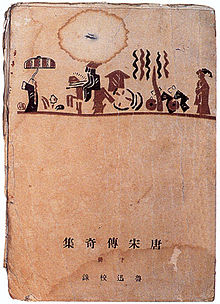

editReferring to fictions written in the Tang dynasty as chuanqi is established by usage.[3]: 7 In the early 1920s the prominent author and scholar Lu Xun prepared an anthology of Tang and Song chuanqi which was the first modern critical edition of the texts and helped to establish chuanqi as the term by which they are known. There is no clear definition of chuanqi, and there are debates regarding what fictions precisely should be included as chuanqi.[1]: 252 [4]: 30 Some scholars have argued that it is not to be used as a general term for all Tang dynasty stories.[5] The scholars Wilt Idema and Lloyd Haft see chuanqi as a general term for stories written in classical Chinese during the Tang and Song dynasties (excluding bianwen Buddhist tales written in the colloquial). Certain scholars hold the opinion that all fictional stories written in Classical Chinese except Biji xiaoshuo are chuanqi, thus making the Qing dynasty the last dynasty where chuanqi was written.[3]: 1 These scholars hold that many of the stories in Pu Songling's 17th-century collection Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio are chuanqi.[6] In this case, chuanqi is sometimes translated as "marvel tales."[7]

Characteristics

editThe chuanqi of the Tang period frequently use incidental poems, set their story in the national capital Chang'an, finish with an instructive moral, and are narrated by someone who claims to have seen the events himself. These stories consisted of anecdotes, jokes, legends, and tales involving mystical, fantastical or legendary elements. The authors did not want to present their works as fiction, but modeled themselves on the literary style of the biographies in the official histories. They went so far as to credit specific people as authorities for the story, however fantastic, and give particular times and places as settings. The authors of these tales were also more careful about the art of storytelling than authors of earlier works, and a number of them have well-developed plots.[8]

The narrative structure of chuanqi is under great influence from Records of the Grand Historian. Therefore, like in historic records, chuanqi usually begins with basic information of the main character—their year of birth and death, origin, noteworthy ancestors and their titles—and end with comments on the event or the character. The origin of the story would also be explained so as to prove its authenticity. Poetry, both in regulated verse and folk song style, is largely used to express emotions, describe a person or scenery, make comments or to mark a turn in the plot.[9]: 75–77 Structure-wise, it is important for chuanqi to have a complete structure and the best works usually meet this standard while having a complex plot. Characterisation-wise, emphasis is laid on the description of a character's psychology and the portrayal of round characters, which is achieved by drawing attention to details and providing different perspectives. Renshi zhuan by Shen Jiji, for example, allows readers to see the characters from multiple perspectives and, with its witty dialogues, gives a cleverly-drawn picture of the triangular relationship of the characters. Yingying's Biography has also created layered characters.[9]: 120–121 Technique-wise, compared to fictions from the Six Dynasties, chuanqi is better at describing scenery, emotions, setting atmosphere and achieving these goals with poetry.[9]: 77 Content-wise, its purpose having developed from telling strange stories to reflecting reality, chuanqi has a large range of themes and reflects different aspects of the society.[10]: 126 Taking Yingying's Biography as an example, it reflects the phenomenon that men with a certain social status would do anything to marry a woman of the same status, even abandoning the love they shared with a common woman.[9]: 121

Development

editIn the Tang dynasty, the increasing social productivity and booming economy led to rising demand for entertainments and cultural activities. The development of urban economy also offered a variety of themes and source material for writers.[10]: 125 Intellectuals began to write invented stories in order to show off their literary talent.[11]: 5 They are all factors that resulted in the popularity of chuanqi.

Certain scholars believe that candidates of the imperial examination in the Tang dynasty often handed in works of chuanqi so as to gain favour from the examiners, which led to the popularity of the form of fiction. An example is that Ji xuan guai lu by Li Fuyan was written during an examination.[12]: 74 However, some scholars think this belief is without foundation.[9]: 75

Early and High Tang

editChuanqi appeared during the reigns of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu Zetian. In Early and High Tang, the number of chuanqi written was limited and their general quality was not as high. The works of that period also bear heavy influence from the zhiguai xiaoshuo popular in the Six dynasties. Only three works are extant today:[4]: 20, 11 Gu jing ji supposedly by Wang Du, Supplement to Jiang Zong's Biography of a White Ape by an anonymous author and You xian ku by Zhang Zhuo. They were all written during the reigns of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu Zetian. None of the chuanqi written in High Tang still remains.[4]: 14, 16–17 Among the three, Supplement to Jiang Zong's Biography of a White Ape is considered to be of the highest quality. In the story, after a white ape abducts a beauty, the husband of the woman enters the ape's palace, kills the white ape and rescues her. The complex personality of the white ape is portrayed in a realistic and fascinating way, making the story a classic among early works of chuanqi.[9]: 127 You xian ku recounts the love affair a man has with two female immortals; graphic description of intercourse can be found in the story.[9]: 83

Middle Tang

editMiddle Tang was the golden age of chuanqi.[4]: 10 There was a great number of new writers and new works. The stories of this period are generally of high quality and rich in both content and form. Although the influence of the old gods and demons fiction still lingered, many stories had begun to reflect reality instead of telling mere fantasies.[9]: 227 The themes are mainly satire, love and history, among which love is the best explored. Some of the best chuanqi are love stories about unions and separations. Representative chuanqi about love include Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen, The Tale of Huo Xiaoyu by Jiang Fang and The Tale of Li Wa by Bai Xingjian. They all have a diversity of realistic characters, which make them the classics.[11]: 227 [9]: 84 Renshi Zhuan written in 781 AD by Shen Jiji is a masterpiece. It marks the beginning of a new era for Tang fiction,[11]: 195–196 where chuanqi was separate from the traditional gods and demons stories and where the focus of a story shifted from the recounting of strange events to the literary use of language and the portrayal of characters. In Renshi Zhuan, Renshi, a fox spirit, seduces the impoverished scholar Zheng. Although Zheng discovers that she is actually a fox, he continues the relationship. Because of his genuine affection and the help of his relative Wei Yin, Renshi marries Zheng as his concubine. At some point, Wei also falls in love with the beautiful Renshi and courts her, but Renshi, being true, is unmoved and refuses him. Years later, Zheng has to journey to take up an official post and wants Renshi to go with him. Renshi is unwilling but is eventually persuaded. She is killed on their way by hounds.[9]: 118–120 Another notable chuanqi is Liushi zhuan by Xu Yaozuo, a story about the courtesan Liushi and her lover Han Hong. Liushi is abducted by a foreign general in a rebellion before being rescued by the fierce warrior Xu Jun and finally reunited with Han Hong.[11]: 222、226 [9]: 85 After the 820s, intellectuals gradually lost interest in writing chuanqi.[11]: 364

Late Tang

editIn the Late Tang, it was once again the trend for chuanqi writers to tell mysterious stories unrelated to real life. There emerged many works about youxia "heroes and knights-errant". The Tale of Wushuang by Xue Diao, Kūnlún nú and Nie Yinniang by Pei Xing, Hongxian Zhuan by Yuan Jiao and The Tale of the Curly-Bearded Guest by Du Guangting are famous examples. Kūnlún nú is the story of a Negrito slave who saves the lover of his master from a harem. Nie Yinniang tells the amazing story of Nie Yinniang's youth—how she learns martial arts and spells under the guidance of an extraordinary Buddhist nun, chooses her own husband, which is unorthodox considering the time period, and does heroic deeds.[9]: 97, 85 A Daughter of the Wei Family by an anonymous author is also a well-known chuanqi written in this period.

Song dynasty

editThe number of chuanqi written in the Song dynasty is few. Some examples are Luzhu zhuan and Yang Taizhen wai zhuan by Yue Shi, Wu yi zhuan by Qian Yi or Liu Fu and Li Shishi wai zhuan by an anonymous author. Among these, the works of Yue Shi are the most outstanding.[9]: 164–166 [13]: 31 In the Song dynasty, because the prominent philosophy, Neo-Confucianism promoted that literature should be a vehicle for ideology, highlighted the educational function of literature and in turn disapproved of unorthodox plots, the freedom and creativity of authors were limited. In the meantime, the rise to popularity of vernacular novels reduced novels in classical Chinese to second place and also led to the decline of chuanqi.[9]: 72、163 The only fictional work from this period that can be counted as chuanqi is Zhi cheng Zhang zhu guan.

Ming and Qing dynasties

editIn Ming and Qing dynasties, vernacular novels were far more popular than those written in classical Chinese.[9]: 238 Many of the latter imitated the themes and writing of chuanqi from Tang and Song dynasties. Certain scholars also categorise them in a broad sense as chuanqi. Typical works from this period include "Jin feng chai ji" from Jiandeng Xinhua by Qu You,[3]: 394 The Wolf of Zhongshan by Ma Zhongxi, and "The Taoist of Lao Mountain", "Xia nu" and "Hong Yu" from Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio by Pu Songling.[14]: xxii Notably, both chuanqi and biji are included in Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio.[15]: 223–224

Themes

editTang chuanqi has four main themes:[14]: xxi

Love

editLove is the most explored theme of chuanqi. Well known chuanqi about love includes The Tale of Huo Xiaoyu by Jiang Fang, The Tale of Li Wa by Bai Xingjian, and Yingying's Biography by Yuan Zhen. The love stories told in chuanqi show criticism to the traditional concept that one must not marry out of their social class and celebrate freedom of choice in love and marriage.[13]: 28 Yingying's Biography is the chuanqi with the most long-lasting influence on later generations. The student Zhang meets Cui Yingying in a temple and falls in love. After a while, they establish a secret sexual relationship and meet each other at night. Months later, Zhang leaves to take the examination and abandons Yingying, believing her to be untrue. His friends all approve of his decision.[15]: 88 [9]: 121 The Tale of Huo Xiaoyu tells the story between poet Li Yi and courtesan Huo Xiaoyu. They originally vow to be life-long lovers, but Xiaoyu worries that their relationship will not last, so she asks Li Yi to put off their marriage for eight years. Having successfully passed the examination, Li Yi becomes an official. Immediately afterwards, he marries a woman from his own elevated social status and avoids Xiaoyu. Xiaoyu falls gravely ill. Dying, she reprimands and curses Li Yi. As a result of the curse, he becomes extremely jealous and abusive, so much so that none of his marriages can last. The Tale of Li Wa, with its clear structure and unpredictable, moving plot, is one of the best works of chuanqi.[10]: 130–132 The story involves a young student who falls in love with the famous courtesan Li Wa. Having spent all his money on Li Wa, he is abandoned by Li Wa and her Madam and then beaten by his father. Injured and impoverished, he roams the street as a beggar until meeting Li Wa again. Li Wa changes her heart and takes him in. She makes him study hard for the examinations. After he successfully passes the examinations, his father reconciles with him and accepts his marriage with Li Wa. The story concludes in a rare happy ending.[9]: 84

Zhiguai (tales of the strange)

editZhiguai chuanqi, influenced by the tradition from the Six Dynasties, contains ideas from both Buddhism and Taoism. For example, Record of an Ancient Mirror written in Early Tang dynasty tells the story of how Wang Du from the Sui dynasty receives an ancient mirror from Hou of Fenyin and slays demons with its help;[11]: 74–82 Liu Yi zhuan by Li Chaowei tells the story of how Liu Yi, when passing the north bank of Jing River after failing the examinations, meets a shepherdess, who turns out to be the daughter of the Dragon King, abused by her husband, and helps her send words to her father.[16] In order to give lessons or express satire, zhiguai chuanqi are often about supernatural beings or another world.[13]: 29 The World Inside a Pillow by Shen Jiji and The Governor of Nanke by Li Gongzuo are two examples. The World Inside a Pillow is a story that advises people to give up the desire for fame and gain. In the story, a student who has failed the examination many times meets a Taoist monk who gives him a porcelain pillow. When the student receives the pillow, the owner of the inn is cooking rice. The student sleeps on the pillow and dreams that he successfully becomes a Jinshi in the exams and is made an official, but is later exiled because of slanders. When he is in despair, he is pardoned and given back his former position. Later in his dream-life he marries, has a large family and finally dies at the age of eighty. When he wakes up, the rice is not yet cooked. Thus he realises that life is no more than a dream.[11]: 293 [9]: 105 In The Governor of Nanke, Chunyu Fen, an unsuccessful officer drinks himself to sleep and dreams about a kingdom where he experiences the ups and downs of life and gains wealth and fame, but when he wakes, he finds that the kingdom is merely a large ants' nest. Chunyu Fen then eschews money and women and becomes a Taoist, although he still feels somewhat attached to the ants' nest.[9]: 105–106 The story satirised the corruption and scramble for power among officials. In terms of satire and writing, it is superior to The World Inside a Pillow.[13]: 32 [11]: 255 Du Zichun, The Engaging Inn and Xin Gongping shang xian written by Li Fuyan in Late Tang dynasty are also noteworthy works of chuanqi. Among them, Xin Gongping shang xian is particular not because of its beautiful writing, but because it uses a ghost story to reveal the secrets behind an assassination of an emperor.[17]

Xiayi (heroism)

editXiayi fictions often reflect the hope for justice and salvation in a time of unrest.[13]: 30 Notable works of chuanqi on this theme include The Tale of Wushuang by Xue Diao, Kunlun Nu by Pei Xing, Xie Xiao'e zhuan by Li Gongzuo, Hongxian zhuan by Yuan Jiao and The Tale of the Curly-Bearded Guest by Du Guangting. In The Tale of Wushuang, the protagonist, beautiful Wushuang, after being abducted to a harem, is given a rare potion which allows her to fake death for three days and is thus rescued by a knight-errant.[9]: 94 Heroic female characters are greatly praised in chuanqi. For example, Hongxian from Hongxian zhuan, who, in order to scare away an enemy of her master, steals their prized golden box from their bedside at night. She later leaves her master to become a bhikkhuni.[9]: 85–86 Similar characters include Xie Xiao'e from Xie Xiao'e zhuan and Nie Yinniang from the eponymous chuanqi. The Tale of the Curly-Bearded Guest is set in at the end of the Sui dynasty when warlords fought for power. The curly-bearded guest seeks to dominate the kingdom, but realises that Li Shimin is destined to be emperor after meeting him. Therefore, he gives all his possession to Li Jing so that the latter can help Li Shimin take the throne. Then the curly-bearded guest leaves to be the king of Buyeo.[10]: 133 The characterisation of heroes in The Tale of the Curly-Bearded Guest has reached an unsurpassed peak in fictions written in classical Chinese.[9]: 117

History

editHistorical fictions among chuanqi include Gao Lishi wai zhuan by Guo Shi, An Lushan shi ji by Yao Runeng, Chang hen ge zhuan and Dong cheng fu lao zhuan by Chen Hong as well as Li Linfu wai zhuan by Anonymous Author. Gao Lishi wai zhuan focuses on the events that happened when the Emperor Xuanzong of Tang fled from the An Lushan Rebellion and the discussions between the emperor and Gao Lishi. Chang hen ge zhuan tells the love story between the Emperor Xuanzong and Yang Guifei and their respective ends—when they flee from the rebellion, the emperor is forced to sentence Yang to death at Mawei Courier Station; after the rebellion is suppressed, the emperor is also forced to abdicate. In the end of the story the emperor meets Yang again in his dream.[9]: 84–85

Translations and studies

edit- Nienhauser, William H., Jr. Tang dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader (Singapore and Hackensack, NJ: World Scientific, 2010).[18] ISBN 9789814287289 Annotated translations of six tales. The Introduction, "Notes for a History of the Translation of Tang Tales," gives a history of the translation of the tales and the scholarship on them.

- Y. W. Ma and Joseph S. M. Lau. ed., Traditional Chinese Stories: Themes and Variations. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978). Reprinted: Boston: Cheng & Tsui, 1986. ISBN 023104058X. Includes 26 selections, ranging from the Tang dynasty to 1916.

- Wolfgang Bauer, and Herbert Franke, The Golden Casket: Chinese Novellas of Two Millennia (New York: Harcourt, 1964 Translated by Christopher Levenson from Wolfgang Bauer's and Herbert Franke's German translations.)

- "The World in a Pillow: Classical Tales of the Tang dynasty," in John Minford, and Joseph S. M. Lau, ed., Classical Chinese Literature (New York; Hong Kong: Columbia University Press; The Chinese University Press, 2000 ISBN 0231096763), pp. 1019-1076.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b 倪豪士(William H. Nienhauser) (2007). 〈唐傳奇中的創造和故事講述〉 (in Simplified Chinese). 北京: 中華書局. pp. 203–252. ISBN 9787101054057.

- ^ Idema and Haft, p. 139.

- ^ a b c 陳文新 (1995). 《[中國傳奇小說史話]》 (in Traditional Chinese). Taipei: 正中書局. ISBN 957090979X.

- ^ a b c d 陳珏 (2005). 初唐傳奇文鈎沉 (in Simplified Chinese). Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Publishing House. ISBN 7532539717.

- ^ Nienhauser, William H. (2010). Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader. Vol. 1. World Scientific. p. xiii. ISBN 9789814287289.

- ^ Y. W. Ma and Joseph S. M. Lau. ed., Traditional Chinese Stories: Themes and Variations. (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978; Reprinted: Boston: Cheng & Tsui, 1986. ISBN 023104058X), pp. xxi-xxii.

- ^ "Pu Songling". Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. 1995. ISBN 0-87779-042-6.

- ^ "The form and content of Chuanqi," in Wilt Idema and Lloyd Haft. A Guide to Chinese Literature. (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan, 1997; ISBN 0892641231), pp. 134-139.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w 莫宜佳(Monika Motsch) (2008). 《中國中短篇敘事文學史》 (in Chinese). 韋凌譯. Shanghai: East China Normal University Press. ISBN 978-7561760765.

- ^ a b c d 柳無忌 (1993). 《中國文學新論》 (in Simplified Chinese). 倪慶餼譯. Beijing: Renmin University Press. ISBN 7300010350.

- ^ a b c d e f g h 內山知也 (2010). 《隋唐小說研究》 (in Simplified Chinese). 益西拉姆等譯. 上海: 復旦大學出版社. ISBN 978-7309069891.

- ^ Chen Yinke (1980). 〈順宗實錄與續玄怪錄〉 (in Traditional Chinese). 上海: 上海古籍出版社. pp. 74–81. ISBN 9787108009401.

- ^ a b c d e 江炳堂 (1992). 內田道夫 (ed.). 〈夢與現實——「傳奇」的世界〉 (in Simplified Chinese). 李慶譯. 上海: 上海古籍出版社. pp. 26–37. ISBN 7532511588.

- ^ a b 馬幼垣(Y. W. Ma)、劉紹銘(Joseph S. M. Lau), ed. (1978). Traditional Chinese Stories: Themes and Variations. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 023104058X.

- ^ a b 魯迅 (1952). 《中國小說史略》 (in Traditional Chinese). 北京: 人民文學出版社.

- ^ 曹仕邦. "〈試論中國小說跟佛教的「龍王」傳說在華人社會中的相互影響〉" (in Traditional Chinese). 國立台灣大學文學院佛學數位圖書館暨博物館. Retrieved 2014-08-28.

- ^ 王汝濤.《宦官殺皇帝的秘錄探微》臨沂師專學報

- ^ Nienhauser, William H. (2010). Tang Dynasty Tales: A Guided Reader. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4287-28-9.

External links

edit- "Chuanqi" Chinaknowledge Ulrich Theobald, Department of Chinese and Korean Studies, University of Tübingen