Chink[1] is an English-language ethnic slur usually referring to a person of Chinese descent,[2] but also used to insult people with East Asian features. The use of the term describing eyes with epicanthic folds is considered highly offensive and is regarded as racist by many.[3][4]

Etymology

editVarious dictionaries provide different etymologies of the word chink; for example, that it originated from the Chinese courtesy ching-ching,[5] that it evolved from the word China,[6] or that it was an alteration of Qing (Ch'ing), as in the Qing dynasty.[7]

Another possible origin is that chink evolved from the word for China in an Indo-Iranian language, ultimately deriving from the name of the Qing dynasty. That word is now pronounced similarly in various Indo-European languages.[8]

History

editThe first recorded use of the word chink is from approximately 1880.[10] As far as is ascertainable, its adjective form, chinky, first appeared in print in 1878.[11]

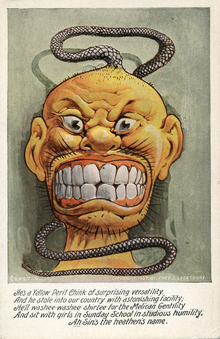

Around the turn of the 20th century, many white Americans in the Northern United States perceived Chinese immigration as a threat to their living standards. However, Chinese workers were still desired in the Western United States due to persistent labor shortages. Chinese butcher crews were held in such high esteem that when Edmund A. Smith patented his mechanized fish-butchering machine in 1905, he named it the Iron Chink[12][13] which is seen by some as symbolic of anti-Chinese racism during the era.[14][15] Usage of the word continued, such as with the story "The Chink and the Child", by Thomas Burke, which was later adapted to film by D. W. Griffith. Griffith altered the story to be more racially sensitive and renamed it Broken Blossoms.

Although chink refers to those appearing to be of Chinese descent, the term has also been directed towards people of other East and Southeast Asian ethnicities. Literature and film about the Vietnam war contain examples of this usage, including the film Platoon (1986) and the play Sticks and Bones (1971, also later filmed).[16][17]

Worldwide usage

editAustralia

editThe terms Chinaman and chink became intertwined, as some Australians used both with hostile intent when referring to members of the country's Chinese population, which had swelled significantly during the Gold Rush era of the 1850s and 1860s.[18]

Assaults on Chinese miners and racially motivated riots and public disturbances were not infrequent occurrences in Australia's mining districts in the second half of the 19th century. There was some resentment, too, of the fact that Chinese miners and laborers tended to send their earnings back home to their families in China rather than spending them in Australia and supporting the local economy.

In the popular Sydney Bulletin magazine in 1887, one author wrote: "No nigger, no chink, no lascar, no kanaka (laborer from the South Pacific islands), no purveyor of cheap labour, is an Australian."[10] Eventually, since-repealed federal government legislation was passed to restrict non-white immigration and thus protect the jobs of Anglo-Celtic Australian workers from "undesirable" competition.

India

editIn India, the ethnic slur chinki (or chinky) is frequently directed against people with East Asian features, including people from Northeast India, and Nepal,[19] who are often mistaken for Chinese, despite being closer to Tibetans and the Burmese than to Han Chinese peoples.[20]

In 2012, the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs recognized use of the term "chinki" to refer to a member of the Scheduled Tribes (especially in the North-East) as a criminal offense under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act with a penalty of up to five years in jail. The Ministry further warned that they would very seriously review any failure of the police to enforce this interpretation of the Act.[21]

United Kingdom

editChinky: Strongest language, highly unacceptable without strong contextualisation. Seen as derogatory to Chinese people. More mixed views regarding use of the term to mean ‘Chinese takeaway’.

Chinky (or chinky chonky[23]) is a slur for a Chinese takeaway restaurant or Chinese food and Chinese people[24] which, in parts of northern England, are known as a chinkies, always in the plural. [citation needed]

The 1969 top 3 UK hit single for Blue Mink, "Melting Pot", has the lyric: "take a pinch of white man/Wrap him up in black skin. [...] Mixed with yellow Chinkees. You know you lump it all together/And you got a recipe for a get-along scene/Oh what a beautiful dream/If it could only come true".[25] In August 2019, British broadcaster Global permanently deleted the song from its Gold playlist after a complaint about offensive language was lodged with British broadcasting regulator Ofcom. Under the direction of the Communications Act 2003, Ofcom ruled that "the phrase 'yellow Chinkies' had the potential to be highly offensive"[26]: 16 and "that the use of derogatory language to describe ethnic groups carries a widespread potential for offence".[26]: 17 Ofcom considered that the passage of time since the song's release and the song's positive message of racial harmony did not "mitigate the potential for offence."[26]: 17–18 Ofcom determined that the "potentially offensive material was not justified by the context"[26]: 18 and ruled the case resolved as the licensee Global had removed the song from Gold's playlist.[26] In September 2019, Scottish community radio station Black Diamond FM removed "Melting Pot" from its playlist and "planned to carry out refresher training with its staff" after two complaints about the song's broadcast were lodged with Ofcom. Ofcom ruled in December 2019 that Black Diamond was in breach of Ofcom's Broadcasting Code because "the potentially offensive language in this broadcast was not justified by the context".[27][28]

In 1999, an exam given to students in Scotland was criticized for containing a passage that students were told to interpret containing the word chinky. This exam was taken by students all over Scotland, and Chinese groups expressed offence at the use of this passage. The examinations body apologized, calling the passage's inclusion "an error of judgement."[29]

In 2002, the Broadcasting Standards Commission, after a complaint about the BBC One programme The Vicar of Dibley, held that when used as the name of a type of restaurant or meal, rather than as an adjective applied to a person or group of people, the word still carries extreme racist connotation which causes offence particularly to those of East Asian origin.[30]

In 2004, the commission's counterpart, the Radio Authority, apologised for the offence caused by an incident where a DJ on Heart 106.2 used the term.[31]

In a 2005 document commissioned by Ofcom titled "Language and Sexual Imagery in Broadcasting: A Contextual Investigation" their definition of chink was "a term of racial offence/abuse. However, this is polarising. Older and mainly white groups tend to think this is not usually used in an abusive way—e.g., let's go to the Chinky—which is not seen as offensive by those who aren't of East Asian origin; Chinky usually refers to food not a culture or race however, younger people, East Asians, particularly people of Chinese origin and other non-white ethnic minorities believe the word 'Chinky, Chinkies or Chinkie' to be as insulting as 'paki' or 'nigger'."[32]

In 2006, after several campaigns by the Scottish Executive, more people in Scotland now acknowledge that this name is indirectly racist.[33] As of 2016[update], British broadcasting regulator Ofcom considers the word to be "Strongest language, highly unacceptable without strong contextualisation. Seen as derogatory to Chinese people. More mixed views regarding use of the term to mean 'Chinese takeaway'".[22]

In 2014, the term gained renewed attention after a recording emerged of UKIP candidate Kerry Smith referring to a woman of Chinese background as a "chinky bird".[34]

United States

editThe Pekin Community High School District 303 teams in Pekin, Illinois were officially known as the "Pekin Chinks" until 1981, when the school administration changed the name to the "Pekin Dragons". The event received national attention.[35][36]

During early 2000, University of California, Davis experienced a string of racial incidents and crimes between Asian and white students, mostly among fraternities. Several incidents included "chink" and other racial epithets being shouted among groups, including the slurs being used during a robbery and assault on an Asian fraternity by 15 white males. The incidents motivated a school-wide review and protest to get professional conflict resolution and culturally sensitive mediators.[37]

Sarah Silverman appeared on Late Night with Conan O'Brien in 2001, stirring up controversy when the word chink was used without the usual bleep appearing over ethnic slurs on network television. The controversy led Asian activist and community leader Guy Aoki to appear on the talk show Politically Incorrect along with Sarah Silverman. Guy Aoki alleged that Silverman did not believe that the term was offensive.[38]

New York City radio station Hot 97 was criticized for airing the "Tsunami Song". Referring to the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake, in which over an estimated 200,000 people died, the song used the phrase "screaming chinks" along with other offensive lyrics. The radio station fired a co-host and producer, and indefinitely suspended radio personality Miss Jones, who was later reinstated. Members of the Asian American community said Miss Jones' reinstatement condoned hate speech.[39]

A Philadelphia eatery, Chink's Steaks, created controversy beginning in 2004 with articles appearing in the Philadelphia Daily News and other newspapers.[40] The restaurant was asked by Asian community groups[41] to change the name. The restaurant was named after the original Jewish-American owner's nickname, "Chink", derived from the ethnic slur due to his "slanty eyes".[42] The restaurant was renamed Joe's in 2013.[43][44][45][46][47]

In February 2012, ESPN fired one employee and suspended another for using the headline "Chink in the Armor" in reference to Jeremy Lin, an American basketball player of Taiwanese and Chinese descent.[48][49] While the word chink also refers to a crack or fissure and chink in the armor is an idiom and common sports cliché, referring to a vulnerability,[50] the "apparently intentional" double entendre of its use in reference to an Asian athlete was viewed as offensive.[51]

In September 2019, after it was announced that Shane Gillis would be joining Saturday Night Live as a featured cast member, clips from Gillis' podcast in 2018 resurfaced, in which Gillis made anti-Asian jokes, including using the word "chink". The revelation sparked public outcry, with several outlets noting the disconnect of hiring Gillis along with Bowen Yang, the show's first Chinese American cast member.[52][53] After Gillis issued what was characterized as a non-apology apology,[54][55] a spokesperson for Lorne Michaels announced Gillis would be let go prior to his first episode due to the controversy.[53]

In May 2021, Tony Hinchcliffe was videotaped insulting Peng Dang, an Asian American comedian who had introduced Hinchcliffe after performing the previous set at a comedy club in Austin, Texas, by referring to Dang as a "filthy little fucking chink".[56] Dang posted the video on Twitter, resulting in heavy backlash against Hinchliffe, who was subsequently dropped by his agency and removed from several scheduled shows.[57]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Also chinky, chinkie, chinki, chinker, chinka, or chinkapoo

- ^ "Chink | Definition of chink by Merriam-Webster". Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ^ Hsu, Huan (21 February 2012). "No More Chinks in the Armor". Slate. Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ McNeal, Greg (18 February 2012). "ESPN Uses 'Chink in the Armor' Line Twice UPDATE- ESPN Fires One Employee Suspends Another". Forbes. Archived from the original on 9 May 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2012.

- ^ Cassell's Dictionary of Slang. Orion Publishing Group. November 2005. ISBN 978-0304366361.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Slang. Oxford University Press. December 2003. ISBN 978-0198607632.

- ^ 21st Century Dictionary of Slang. Random House, Inc. 1 January 1994. ISBN 978-0-440-21551-6.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Slang. Oxford University Press. December 2003. ISBN 978-0-19-860763-2.

- ^ "Automated salmon cleaning machine developed in Seattle in 1903". HistoryLink.org. 1 January 2000. Archived from the original on 7 August 2007. Retrieved 20 July 2007.

- ^ a b Hughes, Geoffrey. An Encyclopedia of Swearing. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe, 2006.

- ^ Tom Dalzell; Terry Victor, eds. (12 May 2005). New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21258-8.

- ^ Jo Scott B, "Smith's Iron Chink – One Hundred Years of the Mechanical Fish Butcher", British Columbia History, 38 (2): 21–22, archived from the original on 23 October 2007

- ^ Philip B. C. Jones. "Revolution on a Dare; Edmund A. Smith and His Famous Fish-butchering Machine" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

The myth arose that Edmund Smith had designed the machine specifically to fire Chinese workers

- ^ Wing, Avra (14 January 2005). "Acts of Exclusion". AsianWeek. Archived from the original on 21 October 2006.

- ^ "HistoryLink.org- the Free Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History". Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Platoon.html Archived 30 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 31 March 2007.[verification needed]

- ^ New York Times, 26 April 1971, p. 10.[verification needed]

- ^ Yu, Ouyang (1993). "All the Lower Orders: Representations of the Chinese Cooks, Market Gardeners and Other Lower-Class People in Australian Literature from 1888 to 1988". Kunapipi. 15 (3). Archived from the original on 10 March 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ "Northeast students question 'racism' in India". CNN-IBN. 6 June 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- ^ "Indians Protest, Saying a Death Was Tied to Bias". The New York Times. 1 February 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ Sharma, Aman (3 June 2012). "North-East racial slur could get you jailed for five years". India Today. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Attitudes to potentially offensive language and gestures on TV and radio, Quick Reference Guide" (PDF). ofcom.org.uk. Ipsos MORI. September 2016. p. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2016.

- ^ Ray Puxley (2004). Britslang: An Uncensored A-Z of the People's Language, Including Rhyming Slang. Robson. p. 98. ISBN 1-86105-728-8.

- ^ "TV's most offensive words". The Guardian. 21 November 2005.

- ^ "Melting Pot Lyrics". metrolyrics.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "The Music Marathon: Gold, 27 May 2019, 12:45". Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin (PDF). Ofcom. 27 August 2019. pp. 15–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Geoff Ruderham: Black Diamond FM 107.8, 2 September 2019, 12:23". Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin (PDF). Ofcom. 12 December 2019. pp. 12–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Complaints upheld against station playing Melting Pot by Blue Mink". RadioToday. 2 December 2019. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ^ "Chinese 'slur' wins apology". BBC News. 29 June 1999. Archived from the original on 9 March 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2007.

- ^ "The Vicar Of Dibley" (PDF). The Bulletin. 56 (56). Broadcasting Standards Commission: 19. 25 July 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2004.

- ^ "Radio Authority Quarterly Complaints Bulletin: April – June 2001" (PDF). Radio Authority. June 2001. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2004.

- ^ The Fuse Group (September 2005). "Language and Sexual Imagery in Broadcasting: A Contextual Investigation" (PDF). Ofcom. p. 85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 April 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ One Scotland Many Cultures 2005/2006 — Waves 6 and 7 Campaign Evaluation (PDF). Scottish Executive. 13 September 2006. ISBN 0-7559-6242-7. ISSN 0950-2254. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2016.

- ^ "Farage defends 'rough diamond' former UKIP candidate". BBC News. 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ "1981: The Pekin Chinks high school team becomes the Pekin Dragons". Chinese-American Museum of Chicago. Archived from the original on 19 August 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Stainbrook, Michael (26 September 2014). "The hunt for 'Red' alternatives". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- ^ Banerjee, Neela (16 February 2001). "Hate Crimes Galvanize U.C. Davis Students". Asianweek.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ "ABC's Politically Incorrect Tackles Comedian's 'Chink' Joke". AsianWeek. 24 August 2000. Archived from the original on 27 May 2006. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ Fang, Jennifer; Fujikawa, James (16 February 2005). "'Tsunami Song' Host Miss Jones Returns". Yellowworld.org. Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- ^ Says, Gary (28 April 2008). "Northeast cheesesteak joint shows prejudice - The Temple News". temple-news.com. Archived from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Aoyagi, Caroline (6 February 2004). "AA Groups demand name change for Philadelphia eatery, "Chink's Steacks"" (PDF). Pacific Citizen. Vol. 138. pp. 1–2. ISSN 0030-8579. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "Only 21, she's leading steak-shop fight". The Asian American Journalists Association – Philadelphia. 1 April 2004. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ^ "Chink's Steaks changing its name". 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Chink's Steaks Sign No Longer Hanging In Northeast Philadelphia « CBS Philly". April 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Joe's Steaks + Soda Shop". Archived from the original on 30 January 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Take that, racists: Eat at Joe's (formerly Chink's Steaks)". Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ "Chink's Steaks Is Now Joe's Steaks + Soda Shop – Foobooz". 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 29 January 2014.

- ^ Boren, Cindy (19 February 2012). "ESPN fires employee for offensive Jeremy Lin headline; "SNL" weighs in". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 20 February 2012.

- ^ Collins, Scott (19 February 2012). "Jeremy Lin and ESPN: Network rushes to quell furor over 'chink' comments". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 19 February 2012.

- ^ "chink in one's armor". Dictionary.com. Houghton Mifflin Company. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Dwyer, Kelly (18 February 2012). "Apparently intentional, ESPN's since-deleted headline about Jeremy Lin was distressing". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- ^ * Sims, David (13 September 2019). "'Saturday Night Live' Made a Mistake Hiring Shane Gillis". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Ho, Vivian (13 September 2019). "SNL adds first Asian cast member while another is under fire over anti-Asian slur". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- "New 'SNL' cast member Shane Gillis responds after video of racist slur resurfaces". Los Angeles Times. 12 September 2019. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- Wright, Megh (13 September 2019). "New SNL Hire Shane Gillis Has a History of Racist and Homophobic Remarks". Vulture. Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Thorne, Will; Low, Elaine (13 September 2019). "New 'SNL' Cast Member Shane Gillis Uses Racist, Sexist, Homophobic Remarks in Resurfaced Material". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ a b Lewis, Sophie (13 September 2019). "New "SNL" cast member Shane Gillis exposed in videos using racist and homophobic slurs". CBS News. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Abad-Santos, Alex (13 September 2019). "Racist jokes by new SNL cast member Shane Gillis prompt backlash — and a non-apology about "risks"". Vox. Archived from the original on 14 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Herreria, Carla (13 September 2019). "New 'SNL' Cast Member Spews Racist Asian Jokes, Slur In Resurfaced Video". HuffPost. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ "Tony Hinchcliffe goes on racist rant after being introduced by Asian-American comedian". The Daily Dot. 12 May 2021. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "Comedian Tony Hinchcliffe dropped by WME and Joe Rogan gigs after slur against Chinese comedian: reports". New York Daily News. 13 May 2021. Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

Sources

edit- Foster, Harry. A Beachcomber in the Orient. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1930.