Jiyuan (simplified Chinese: 济远; traditional Chinese: 濟遠; pinyin: Jiyuan, sometimes Chiyuan; Wade–Giles: Tsi Yuan), was a protected cruiser of the Imperial Chinese Navy, assigned to the Beiyang Fleet. She was constructed in Germany as China lacked the industrial facilities needed to build them at the time. Jiyuan was originally intended to be the third ironclad battleship of the Dingyuan class, but was reduced in size due to funding issues. Upon completion, she was prevented from sailing to China during the Sino-French War.

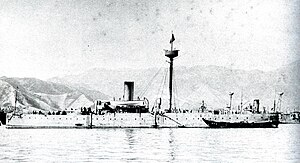

Japanese cruiser Saien (formerly the Chinese cruiser Jiyuan) at Kure in March 1895

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Jiyuan |

| Builder | AG Vulcan Stettin, Stettin, Germany |

| Laid down | 16 January 1883 |

| Launched | 1 December 1883 |

| Completed | August 1884 |

| Commissioned | 11 June 1885 |

| Fate | Prize of war to Japan, 16 March 1895 |

| Name | Saien |

| Acquired | 16 March 1895 |

| Fate | Mined off Port Arthur, 30 November 1904 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Protected cruiser |

| Displacement | 2,300 long tons (2,337 t) |

| Length | 236 ft (71.9 m) |

| Beam | 34.5 ft (10.5 m) |

| Draught | 17 ft (5.2 m) |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion | 2 × Compound-expansion steam engines, two shafts |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Complement | 180 |

| Armament |

|

| Armour |

|

In the First Sino-Japanese War, she was involved in the Battle of Pungdo, and at the Battle of Yalu River, which resulted in the subsequent execution of her captain. She was captured by the Imperial Japanese Navy as a prize of war at the Battle of Weihaiwei, and commissioned as Saien (済遠 巡洋艦, Saien jun'yōkan) on 16 March 1895. Under the Japanese flag, she was used to bombard positions in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan, and was sunk on 30 November 1904 after striking a Russian mine during the Battle of Port Arthur of the Russo-Japanese War.

Design

editWhen Jiyuan was originally ordered by the Imperial Chinese Navy, she was to be the third Dingyuan-class ironclad battleship built by AG Vulcan Stettin in Stettin, Germany. The Chinese had been seeking larger warships from British shipyards, but negotiations had stalled. They turned instead to German shipyards, who the Chinese managed to negotiate a deal with. The orders for the three ironclads were placed following the construction of the German Sachsen class. Due to funding issues, she was instead reduced in size to that of a protected cruiser, and the planned build of up to a dozen ships was reduced to just those three.[1]

Jiyuan displaced 2,300 long tons (2,337 t) and measured 236 feet (72 m) long overall, with a beam of 34.5 ft (10.5 m) and an average draft of 17 ft (5.2 m). The propulsion system consisted of a 2,800 indicated horsepower (2,100 kilowatts) produced by a pair of compound-expansion steam engines with two shafts, enabling a cruising speed of 15 knots (28 kilometres per hour; 17 miles per hour). She was normally fitted with a single military mast, but for the sea voyage from Germany to China she was equipped with additional masts and sails.[2]

Jiyuan's armour consisted of two 10 in (254.0 mm) thick steel barbettes around her main guns, 2 in (51 mm) thick gun shields around the others, and 3 in (76 mm) thick deck armour. Her main armament was her two breech-loading 8.2 in (210 mm) Krupp guns, mounted in a barbette towards the front of the ship. She had a further 5.9 in (150 mm) Krupp gun mounted in a rear barbette, five Hotchkiss guns and four above water mounted torpedo tubes.[2]

Career

editChina

editJiyuan was laid down on 16 January 1883. After being launched from the yard in Stettin on 1 December, she was completed in August the following year. Due to the ongoing Sino-French War, the three Stettin-built ships were prevented from travelling to China and were held up for the following ten months.[3] On 3 July 1885, Jiyuan, Dingyuan and Zhenyuan set off from Kiel, Germany, on the voyage to China, equipped with a German crew. They stopped on the way in Devonport, England; Gibraltar; Aden, Yemen and Colombo, Sri Lanka. At the end of October, the ships arrived at the Taku Forts in China, where Chinese crews were embarked. Their arrival signalled the creation of a new post-war Beiyang Fleet with the battleships at the centre of the formation.[4]

The fleet was based out of the newly expanded Port Arthur (now Lüshunkou District), however since the port froze over during the winter, both Jiyuan and the battleships would spend part of the year in Shanghai. The three ships worked up alongside the cruisers Chaoyong and Yangwei in exercises held in 1886.[5] Several ships of the Beiyang Fleet sailed to Hong Kong from Shanghai at the end of 1889, including Jiyuan. They sailed onto Singapore, before returning to Shanghai during the following April.[6]

First Sino-Japanese War

editBy the time of the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Jiyuan was captained by Fang Pai-chen.[7] She was among several ships to be assigned as escorts to troopships heading to Korea in June 1894. Jiyuan departed on 22 July alongside the gunboat Kuang Yi from Weihaiwei (now Weihai) for Asan in Korea, beginning the return journey on 25 July. The two ships were meant to meet up with the troopship Kowshing, but instead were confronted by three cruisers of the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Battle of Pungdo. Jiyuan attempted to pass close to the Japanese cruiser Naniwa, as her captain anticipated a short-range torpedo attack. The other two Japanese cruisers, Yoshino and Akitsushima also began firing on Jiyuan.[8]

Jiyuan was hit by a multitude of shells, disabling her forward-mounted Krupp gun and severely damaging all the structures above her armour belt. Captain Fang gave orders to flee at full speed towards Waihaiwei, with Yoshino in pursuit. Reports differed on why Jiyuan was not overtaken by the faster Japanese cruiser, with one claim stating that Jiyuan's aft mounted Krupp gun scored a hit on the bridge of the Yoshino, and another indicating that the shot was fired by the Kuang Yi. While Jiyuan got away, the Kuang Yi fought against the remaining two cruisers until she was holed and sank, at which point she was beached to allow her crew to escape. As the Tsi Yuan headed to Weihaiwei, she passed the Kowshing which was still heading to Korea. The troop ship was stopped by the Japanese, and after prolonged negotiations she was sunk with a loss of a great number of the troops and crew on board.[8]

Upon her arrival at Weihaiwei, she was sent to Port Arthur for repairs.[9] Captain Fang of the Jiyuan was court-martialled for his actions but found not guilty and returned to duty.[10] Jiyuan was repaired and rejoined the fleet on 7 August in Weihaiwei, shortly before the Japanese attacked the port three days later, bombarding the defensive forts before leaving.[9] On 17 September, at the Battle of Yalu River, she was at the far left of the Chinese line and in a fighting pair with the cruiser Guangjia.[11] Jiyuan signalled early on that she was damaged, and was withdrawn. The ship was manoeuvred into some nearby shallows where the crew found it difficult to steer the vessel, and instead steamed back into the engagement.[10] While doing so, it collided with the Chinese cruiser Chaoyong, which subsequently sank.[12] At some point during the battle, Captain Fang was relieved of his duties by First Lieutenant Shen Sou Ch'ang, but Fang returned to command after Shen was killed.[13]

Jiyuan then travelled back to Port Arthur, where the foreign engineer refused to serve the captain of the vessel any longer, and left. Captain Fang Peh-Kien was executed for his actions in the battle,[11][10] with command passed to First Lieutenant Huang Tsu-Lien.[13] Of the surviving Chinese warships from the battle, the Jiyuan was the least damaged.[14] As the other surviving ships from the battle arrived in Port Arthur, their guns were dressed in red. Jiyuan was the exception, with no decoration and was docked away from the other vessels.[15]

She was of one several Chinese ships caught in the harbour of Weihaiwei when the Japanese laid siege over the winter in early 1895 in the Battle of Weihaiwei.[16] Huang refused to leave Jiyuan to seek treatment for injuries sustained during the battle; instead his wounds were dressed and he continued in his duties. He was then shot through the thigh, and continued to refuse treatment. A few minutes later he was killed by an explosive shell fired by a Japanese vessel.[13] Admiral Ding Ruchang, in command of the fleet, surrendered on 12 February, and committed suicide shortly afterwards. In exchange for the surrender of all war material including the fleet, good behaviour was promised by the Japanese.[17] Jiyuan was later commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy as Saien, the same Chinese character name.[18]

Japan

editSaien was pressed immediately into Japanese service. During the Japanese invasion of Taiwan later in 1895, she was assigned together with six other ships to bombard the coastal defences of Takow (Kaohsiung). The fleet arrived off the coast on 12 October, warning foreign vessels that the attack would begin at 7am the following morning. The Japanese ships attacked on schedule, firing on the defenses until they stopped returning fire after half an hour. At 2pm, the ships closed the distance to the beach and began launching boats into the water with troops. Their forces had successfully captured the coastal fort by 2:35pm.[19]

The Japanese refitted Saien in 1898, replacing her existing light guns with eight quick-firing 3 pounders.[20][21] While supporting the Imperial Japanese Army following the Battle of Port Arthur during the opening stages of the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, Saien struck a submerged Russian mine on 30 November 1904. Eight crewmen in the engine room were killed immediately by the explosion, with the cruiser sinking rapidly over the following two minutes. During this time only two boats could be launched, saving 70 of the crew, along with a collection of various items entrusted to them by the officers such as the signal book and some paintings of the Imperial family.[22]

The gunboat Akagi was nearby bombarding enemy positions, and diverted to the Saien following the explosion. Together, a total of 191 officers and crew were saved between the launches, the Akagi and another gunboat. Saien's Captain Tajima was lost, as were another 39 men.[23] The wreck is located at 38°51′N 121°05′E / 38.850°N 121.083°E.[20] The loss of the Saien was thought to be insignificant due to her age and capabilities compared to the other ships of the Japanese fleet. She was one of several Japanese ships to be mined out of Port Arthur during the period including the pre-dreadnought battleships Hatsuse and Yashima, which demonstrated the usefulness of naval mines for harbour defence.[24]

Notes

edit- ^ Wright 2000, p. 50.

- ^ a b Wright 2000, p. 53.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 54.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 66.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 81.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 87.

- ^ a b Wright 2000, p. 88.

- ^ a b Wright 2000, p. 89.

- ^ a b c "War News by Mail". Queensland Times. 27 October 1894. p. 7. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ a b Wright 2000, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 91.

- ^ a b c "A Brave Chinese Officer". Traralgon Record. 23 August 1901. p. 1. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 93.

- ^ "The Chinese Methods of Warfare". The Sydney Mail. 3 November 1894. p. 927. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 98.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Wright 2000, p. 105.

- ^ Davidson 1903, pp. 357–358.

- ^ a b Jentschura, Jung & Mickel 1977, p. 99.

- ^ Chesneau & Kolesnik 1979, p. 229.

- ^ "Loss of a Japanese Cruiser". Brisbane Courier. 13 February 1905. p. 5. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Trove.

- ^ Cassell's 1905, p. 408.

- ^ "Comments on the Situation". Sydney Morning Herald. 12 December 1904. p. 7. Retrieved 19 December 2016 – via Trove.

References

edit- Cassell's History of the Russo-Japanese War. London; Paris; New York; Melbourne: Cassell and Company. 1905.

- Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich, UK: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Davidson, James W. (1903). The Island of Formosa, Past and Present. London; New York: Macmillan & Co.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Stille, Mark (2016). The Imperial Japanese Navy of the Russo-Japanese War. London: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4728-1121-9.

- Wright, Richard N.J. (2000). The Chinese Steam Navy. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86176-144-6.