Depictions of nudity include all of the representations or portrayals of the unclothed human body in visual media. In a picture-making civilization, pictorial conventions continually reaffirm what is natural in human appearance, which is part of socialization.[1] In Western societies, the contexts for depictions of nudity include information, art and pornography. Information includes both science and education. Any image not easily fitting into one of these three categories may be misinterpreted, leading to disputes.[2] The most contentious disputes are between fine art and erotic images, which define the legal distinction of which images are permitted or prohibited.

A depiction is defined as any lifelike image, ranging from precise representations to verbal descriptions. Portrayal is a synonym of depiction, but includes playing a role on stage as one form of representation.

Nudity in art

edit-

Venus of Willendorf (circa 29,500 years ago)

-

The Antikythera Youth (70-60 BC)

-

Portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune (1550 to 1555) by Angelo Bronzino

-

La maja desnuda (c. 1800) by Francisco Goya

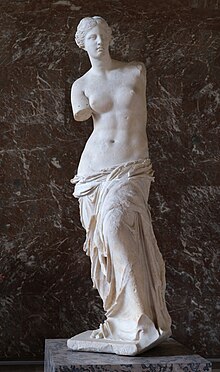

Nudity in art—painting, sculpture, and more recently photography—has generally reflected social standards of the time in aesthetics and modesty/morality. At all times in human history, the human body has been one of the principal subjects for artists. It has been represented in paintings and statues since prehistory. Venus figurines are well-known examples from this era.

For the ancient Greeks, male nudity was considered heroic and sensually pleasing. This attitude is reflected in their artworks, which portray the human body in idealized form. In addition, it was perfectly acceptable for a man to openly admire the physique of another.[3] Vase paintings and sculptures of nude women were also made, exhibiting the female counterpart to heroic nudity in men.[3][4] One example of such an artwork is the sculpture Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles of Athens from the fourth century B.C.[4]

Bronzino's so-called "allegorical portraits" such as the Portrait of Andrea Doria as Neptune, of Genoese Admiral Andrea Doria, are less typical but possibly even more fascinating due to the peculiarity of placing a publicly recognized personality in the nude as a mythical figure, Neptune or Poseidon, god of the sea and earthquakes. Although naked, Doria is not fragile or frail. He is depicted as a powerful virile man, showing masculine spirit, strength, vigor, and power.[5][6]

Portraits and nudes without a pretense to allegorical or mythological meaning were a fairly common genre of art from the Renaissance onwards. Some regard Francisco Goya's La maja desnuda of around 1800, as "the first totally profane life-size female nude in Western art",[7] but paintings of nude females were not unknown, even in Spain. The painting was hung in a private room, along with other nudes, including the much earlier Rokeby Venus by Velasquez.

Decorative or monumental art

edit-

The Three Graces (1931) by Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, McGill University Downtown Campus, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Religious and mythological art

edit-

David and Abishag (1879) by Pedro Américo, depicting a story from the Hebrew Bible. Abishag was a servant of King David.

-

Thetis Dipping Achilles into the River Styx (1789) by Thomas Banks. This marble sculpture depicts a famous scene from Greek mythology.

During the Middle Ages, Christianity was unable to completely erase pagan influences in Europe. By the Renaissance, interest in classical civilization was revived, and Greek mythology served as an inspiration for a plethora of artworks.[8] Moreover, the Judeo-Christian tradition has itself inspired a number of nude sculptures and paintings.

Depictions of youth

edit-

The Manneken Pis in Brussels, Belgium. The original bronze statue was created by Jerome Duquesnoy in 1619.

-

After the Bath (1875) by William-Adolphe Bouguereau

-

The Bathers (1889) by Henry Scott Tuke

For centuries, child nudity was common in paintings that depicted allegorical or religious stories. Modern painters have created images of nude children that depict everyday life. Some sculptures depict nude child figures. A particularly famous one is Manneken Pis in Brussels, showing a nude young boy urinating into the fountain below. A female equivalent is Jeanneke Pis. Henry Scott Tuke painted nude young boys doing everyday seaside activities, swimming, boating, and fishing; his images were not overtly erotic, nor did they usually show their genitals.[9] Otto Lohmüller became controversial for his nude paintings of young males, which often depicted genitals. Balthus and William-Adolphe Bouguereau included nude girls in many of their paintings. Professional photographers such as Will McBride, Jock Sturges, Sally Mann, David Hamilton, Jacques Bourboulon, Garo Aida, and Bill Henson have made photographs of nude young children for publication in books and magazines and for public exhibition in art galleries. According to some,[citation needed] photographs such as these are acceptable and should be (or remain) legal since they represent the unclothed form of the children in an artistic manner, the children were not sexually abused, and the photographers obtained written permission from the parents or guardians. Opponents suggest that such works should be (or remain) banned and represent a form of child pornography, involving subjects who may have experienced psychological harm during or after their creation.[10]

Sturges and Hamilton were both investigated following public condemnation of their work by Christian activists including Randall Terry. Several attempts to prosecute Sturges or bookseller Barnes & Noble have been dropped or thrown out of court and Sturges's work appears in many museums, including New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art.[11][12][13]

There have been incidents in which snapshots taken by parents of their infant or toddler children bathing or otherwise naked were destroyed or turned over to law enforcement as child pornography.[14] Such incidents may be examples of false allegation of child sexual abuse. Author Lynn Powell described the prosecution of such cases in terms of a moral panic surrounding child sexual abuse and child pornography.[15]

Colonialism

editIn the nineteenth century, Orientalism represented the European view of the Muslim cultures of North Africa and Asia. Representations of nude Muslim women included "French postcards" for popular distribution, which escaped legal sanctions by being placed in the category of ethnography rather than porn. In the fine arts, many painters used the trope of the harem as an acceptable context for nude and seminude women.[16]

Nude photography

editPhotography has been used to create images of nudity that fit into any category; artistic, educational, commercial, and erotic. In the artistic case, nude photography is a fine art because it is focused aesthetics and creativity; any erotic interest, though often present, is secondary.[17] This distinguishes nude photography from both glamour photography and pornographic photography. The distinction between these is not always clear, and photographers tends to use their own judgment in characterizing their own work,[18][19][20] though viewers may disagree. The nude remains a controversial subject in all media, but more so with photography due to its inherent realism.[21] The male nude has been less common than the female, and more rarely exhibited.[22][23]

Alfred Cheney Johnston (1885–1971) was a professional American photographer who often photographed Ziegfeld Follies showgirls, such as Virginia Biddle.[24] During the First World War, nude images of Fernande by the photographer Jean Agélou where cherished by soldiers on both sides, even though these were illegal and had to be handled with discretion.[25][26]

-

Photograph of the back of a woman with an hourglass figure (c. 1900)

-

Refracted Sunlight on Torso (1922) by Edward Weston

-

Virginia Biddle (1927) by Alfred Cheney Johnston

-

One of the many photographs of Fernande by Jean Agélou (1910s)

Male naked bodies were not pictured as frequently at the time. An exception is the photograph of the early bodybuilder Eugen Sandow modelling the statue The Dying Gaul, illustrating the Grecian Ideal which he introduced to bodybuilding.

Popular culture

editClassifications and disputes

edit-

Ariadne Asleep on the Island of Naxos (1808–1812) by John Vanderlyn. The painting was initially considered too sexual for display in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. "Although nudity in art was publicly protested by Americans, Vanderlyn observed that they would pay to see pictures of which they disapproved."[27]

-

The decision to temporarily remove the painting Hylas and the Nymphs (1896) by John William Waterhouse from public display at the Manchester Art Gallery due concerns over the objectification of women was poorly received by the general public.[28]

With the expansion of the display of nudity in art beyond traditional galleries, some exhibitions experience backlash from individuals who equate all nudity with sexuality, and thus inappropriate for viewing by the general public or schoolchildren in art class.[29][30] In exceptional cases, even well-known artworks, such as the statue David (of the Biblical David) by Renaissance master Michelangelo, could stir controversy.[31] On the other hand, the removal of a famous nude painting from public display, however temporary, could cause a mostly condemnatory public reaction.[28][32] Nude depictions of women may be criticized by feminists as inherently voyeuristic due to the male gaze.[33] Although not specifically anti-nudity, the feminist group Guerrilla Girls point out the prevalence of nude women on the walls of museums but the scarcity of female artists. Without the relative freedom of the fine arts, nudity in popular culture often involves making fine distinctions between types of depictions. The most extreme form is full frontal nudity, referring to the fact that the actor or model is presented from the front and with the genitals exposed. Frequently, though, nude images do not go that far. They are instead deliberately composed, and films edited, such that in particular no genitalia are seen, as if the camera by chance failed to see them. This is sometimes called "implied nudity" as opposed to "explicit nudity." It is in popular culture that a particular image may lead to classification disputes.[2]

Displays of nude artworks in museums may sometimes be a subject of controversy. In response, a museum may showcase only relatively tame statues or paintings, leaving more provocative works to commercial galleries.[34][35] According to art historian Kenneth Clark, a fine work of art may contain significant sexual content but without being obscene.[36] Art historian and critic Frances Borzello observes that twenty-first-century artists have abandoned the ideals and traditions of the past, choosing instead to create more confronting depictions of the unclothed human body. In the performing arts, then, this means presenting actual naked bodies as works of art.[37]

Activism and advertising

edit-

Liberty Leading the People (1830) by Eugène Delacroix, restored in 2024

-

The Greek Slave by Hiram Powers (1851)

-

Photograph from an advertisement for Philips tanning lamps, taken by Maria Antonia Merkelbach (c. 1946)

Liberty Leading the People is an artwork by Romanticist painter Eugène Delacroix commemorating the Revolution of July 1830 in France. It features a partially nude goddess or allegory of liberty, wearing a Phrygian cap that had become the symbol of liberty during the first French Revolution of 1789, holding aloft the French tricolor, and leading citizens from all walks of life to overthrow King Charles X.[38] This painting is sometimes mistakenly believed to portray the French Revolution.[39][40] It is arguably the best known early depiction Marianne, the personification of the French Republic.[41]

Neoclassical sculptor Hiram Powers earned his fame for The Greek Slave,[42][43] a statue that not only inspired some poetry,[43] but also the abolitionist[44][45] and women's rights movements in the United States.[46][47]

In modern media, images of partial and full nudity are used in advertising to draw attention. In the case of attractive models this attention is due to the visual pleasure the images provide; in other cases it is due to the relative rarity of such images. The use of nudity in advertising tends to be carefully controlled to avoid the impression that a company whose product is being advertised is indecent or unrefined. There are also (self-imposed) limits on what advertising media such as magazines will allow. The success of sexually provocative advertising is used to justify the truism "sex sells"—now commonly accepted and utilized by advertisers.[48][49] Nevertheless, some cultures (such as France) are more receptive to the use of sexual appeal in advertising than others (such as South Korea).[50][51] In the United States, responses to nudity has been mixed. Nudity in the advertisements of Calvin Klein, Benetton, and Abercrombie & Fitch, for example, has provoked negative as well as positive responses.

An example of an advertisement featuring male full frontal nudity is one for M7 fragrance. Many magazines refused to place the ad, so there was also a version with a more modest photograph of the same model.

Aircraft nose art

editAn air crew may commission or create an artwork located on the fuselage of the aircraft, usually the nose. Nose art may portray largely unclothed or nude women. Examples of nose arts could be dated back to the First World War. But it was not until the Second that this movement truly took off. Nose arts could be found on both Allied and Axis aircraft. Some observers have argued that the Second World War was the golden age for this style of art.[52] However, after the Korean War, a combination of changing public attitudes and military regulations have diminished the number of nose arts.[53][54] In the United States, for example, the Air Force requires nose arts to be "distinctive, symbolic, gender neutral, intended to enhance unit pride, designed in good taste."[54]

-

Nose art on a B-17 Flying Fortress of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF)

-

Restored "Sugar's Blues" artwork on an Avro Lancaster of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)

Calendars and posters

editIn some countries, calendars with nude imagery are available for purchase. In addition, nude calendars might be sold for charity[55] or by an athletic team.[56][57] In the case of the Orthodox Calendar, the explicit purpose is to combat homophobia.[58][59] The Pirelli Calendar has historically contained glamour photography, some of which nude.[60] Posters featuring nudity might be commercially available as well.

-

A poster dated 1897 archived by the Boston Public Library

-

Isle of Dreamy Melodies (1925-30) by Edward Mason Eggleston, published with that name as a calendar print by Brown & Bigelow.

-

Helen of Troy 1934 calendar print, by Henry Hintermeister

Comic books

editIn 1998, two French cartoonist partners Regis Loisel and Philippe Sternis made the feral child graphic novel (bande dessinée) Pyrénée as the cover, and page story in nude.

Depictions of public figures

edit-

Statue of Queen Arsinoe II of the Ptolemaic Dynasty in Egypt (3rd century B.C.)

-

Memory of Olive Thomas or the Lotus Eater by Alberto Vergas (1920)

Due to high demand, nude imagery of celebrities a lucrative business exploited by websites and magazines, both on and offline. Such depictions include not just authorized images—such as film stills or screenshots, movie clips, copies of previously published images, like photographs for magazines—but also unauthorized ones, including sex tapes and paparazzi photos capturing celebrities in their private moments, and deceptively manipulated images.

Some actors and models have their photographs portraying them in various glamorous poses, oftentimes with scant or even no clothing, called pin-up art.

Playboy magazine was known for offering celebrities large amounts of money to appear nude in its magazine, and more downmarket pornographic magazines search far and wide for nude pictures of celebrities taken unaware—for example, when they are bathing topless or nude at what the subject thought was a secluded beach, or taken before the individual was well known. Paparazzi-produced photos are in high demand among sensationalist magazines and tabloids.

The Pirelli Calendar has historically contained images of women—many of whom actresses or models—in sexual or erotic poses. However, due to changing times, Pirelli, an Italian tyre manufacturing firm, has moved away from this kind of photography.[61][62]

In some countries, privacy law and personality rights can lead to civil action against organizations that publish photos of nude celebrities without a model release, and this restricts the availability of such photos through the print media. On the internet, the difficulty of identifying offenders and applying court sanction makes circulation of such photographs much less risky. Such photographs circulate through online photo distribution channels such as usenet and internet forums, and commercial operators, often in countries beyond the reach of courts, also offer such photos for commercial gain. Copyright restrictions are often ignored.

Films and television

edit-

Ulla Jacobsson and Folke Sundquist in the 1951 film Hon dansade en sommar ("One Summer of Happiness")

-

Jayne Mansfield in Promises! Promises! (1963)

In Western countries, nudity in film was historically deemed scandalous. For example, when the Swedish film Hon dansade en sommar ("One Summer of Happiness") was released 1951, it stirred considerable controversy because of a sequence involving nude swimming (or skinny dipping) and a close-up scene of sexual intercourse in which the breasts of Ulla Jacobsson were visible to the audience. (It also portrayed a local priest as the main antagonist.) As a result, in spite of its awards, the film was banned in Spain and several other countries.[63] It was not widely released in the United States until 1955,[64] although it was showing in San Francisco as early as October 1953.[65] The film is the story of a young and innocent farm girl (played by Jacobsson) in love.[66] In the United States, Promises! Promises! (1963) was the first feature film of the sound era in which a mainstream star (Jayne Mansfield) appeared in the nude.[67]

However, today, nudity in film is no longer as controversial and may even be treated as natural. Nudity is frequently shown in scenes considered to require it, such as those that take place in nature, in the restroom, or those that involve intimacy. The Blue Lagoon (1980), a coming-of-age romantic and survival drama, shows the sexual awakening of two adolescent cousins of the opposite sex who find themselves stranded on a tropical island where nudity is a natural part of the environment, unlike the Victorian constraints of their upbringing.[68] The relationship between a painter and his model, who oftentimes poses in the nude, is the context of a number of films. In the 1991 movie La Belle Noiseuse ("The Beautiful Troublemaker") the painter finds his motivation reinvigorated by his model.[69] Similarly, in Titanic (1997) Rose Dewitt Bukater (played by Kate Winslet) poses nude for Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio).[70] Nudity may also be portrayed in routine and non-sexual contexts. For instance, in Starship Troopers (1997), a mixed-shower scene is intended to demonstrate gender equality in the future.[71][72]

However, whether a nude scene is tasteful or gratuitous could still be a matter of debate.[73][74] Women are generally more likely to be shown partially or entirely nude on screen compared to men. Depending on the context, however, this is not necessarily for the benefit of the male gaze, especially if the female character in question is shown to have agency or if the actress playing her has a say in how much is shown and how.[73] In the United States and Canada, nudity clauses are a standard part of the contracts signed by actors.[75] But things were different in, say, France.[76] The 2013 film Blue Is the Warmest Colour proved to be controversial not necessarily because it depicted a lesbian relationship for which it has been praised, but because of the conditions under which the starring actresses were forced to work by the director. In an interview with The Daily Beast, actress Adèle Exarchopoulos stated, "Most people don’t even dare to ask the things that he did, and they’re more respectful."[73][76] In the aftermath of the MeToo movement in 2017, actresses have become increasingly willing to voice their concern over explicit nudity or sexuality on screen. Many film sets now recruit intimacy coordinators to ascertain the comfort, safety, and consent of all those involved in the shooting of such scenes.[77] Controversy could also ensue if the actors were teenagers at the time of filming.[74] As April Pearson, who was cast as Michelle Richardson in Skins (2007–2013), explained, "There’s a difference between being officially old enough and mentally old enough."[74]

Lust, Caution (2007) is a Chinese-language erotic, historical, romantic, and mystery film based on the 1979 novella of the same name by Eileen Chang. The film is inspired by the real-life Chinese spy Zheng Pingru and her failed attempt to honey-trap and assassinate the Japanese collaborator Ding Mocun during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[78] It was a critical and commercial success not just in Greater China but also internationally.[79][80] In Taiwan and Hong Kong, it was screened uncut, but in mainland China, some scenes were censored.[81] In South Korea, nudity in films is no longer unusual. In 2012 alone, the movies Eungyo, The Concubine, and The Scent were released with commercial success. However, critics argued that it was not nudity that led to their popularity among viewers but rather compelling plots.[82]

Due to the culture of the United States, MTV, VH1, and other music-related television channels usually censor what they deem offensive or otherwise inappropriate for their viewers.[83] For example, the music video for the song "Justify My Love" (1990) by Madonna contained a number of sexual fetishes and was consequently rejected by MTV.[84] As Rolling Stone contributing editor Anthony Curtis explained, "...there's this kind of adolescent sexuality, with a lot of talking and looking and fantasizing. Through the years, MTV has done a very effective job of dancing up to the line without going over it. And that approach seems to work for them."[83] In the United Kingdom, the Independent Broadcasting Authority, which regulated television and radio programming, banned the music video from being aired before nine o'clock in the evening.[84]

Magazine covers

editIn the early 1990s, Demi Moore posed nude for two covers of Vanity Fair: Demi's Birthday Suit and More Demi Moore. Later examples of implied nudity in mainstream magazine covers[85] have included:

- Janet Jackson (Rolling Stone, 1993)

- Jennifer Aniston (Rolling Stone, 1996 and GQ, January 2009)

- The Dixie Chicks (Entertainment Weekly, May 2003)

- Scarlett Johansson and Keira Knightley (Vanity Fair, March 2006)

- Serena Williams (ESPN The Magazine's Body issue, 2009)

- Alexander Skarsgård, Anna Paquin and Stephen Moyer; from the cast of True Blood (Rolling Stone, September 2010)

- Kim Kardashian (W, November 2010)

- Lake Bell (New York Magazine, August 2013)[86]

- Miley Cyrus (Rolling Stone, October 2013)[87]

Music album covers

editNudity is occasionally presented in other media, often with attending controversy. For example, album covers for music by performers such as Jimi Hendrix, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Nirvana, Blind Faith, Scorpions, Jane's Addiction, and Santana have contained nudity. Several rock musicians have performed nude on stage, including members of Jane's Addiction, Rage Against the Machine, Green Day, Black Sabbath, Stone Temple Pilots, The Jesus Lizard, Blind Melon, Red Hot Chili Peppers, blink-182, Naked Raygun, Queens of the Stone Age and The Bravery.

The provocative photo of a nude prepubescent girl on the original cover of the Virgin Killer album by the Scorpions also brought controversy.

Erotic depictions

edit-

A clay plague of a couple having sexual intercourse in the missionary position, from Old Babylon (2nd millennium B.C.)

-

An erotic sculpture from a temple at Khajuraho, India, 10th century A.D.

-

Erotic artworks such as this one (A.D. 1799) served as a guide for newly married couples in Japan.

Sexually explicit images, other than those having a scientific or educational purpose, are generally categorized as either erotic art or pornography, but sometimes can be both.

Early cultures often associated the sexual act with supernatural forces and thus their religion is intertwined with such depictions. In Asian polities such as India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Japan, Korea, and China, erotic artworks and other representations of human sexuality have specific spiritual meanings within their respective native religions. In Europe, ancient Greece and Rome produced much art and decoration of an erotic nature, much of it integrated with their own religious beliefs and cultural practices.[88][89]

Japanese painters like Hokusai and Utamaro, in addition to their usual themes also executed erotic depictions. Such paintings were called shunga (literally: "spring" or "picture of spring"). They served as sexual guidance for newly married couples in Japan in general, and the sons and daughters of prosperous families were given elaborate pictures as presents on their wedding days. Most shunga are a type of ukiyo-e, usually executed in woodblock print format.[90] It was traditional to present a bride with ukiyo-e depicting erotic scenes from the Tale of Genji.

Shunga were relished by both men and women of all classes. Superstitions and customs surrounding shunga suggest as much; in the same way that it was considered a lucky charm against death for a samurai to carry shunga, it was considered a protection against fire in merchant warehouses and the home. The samurai, chonin, and housewives all owned shunga. All three of these groups would undergo separation from the opposite sex; the samurai lived in camps for months at a time, and conjugal separation resulted from the sankin-kōtai system and the merchants' need to travel to obtain and sell goods.[91] Records of women obtaining shunga themselves from booklenders show that they were consumers of it.[90]

The Khajuraho temples contain sexual or erotic art on the external walls of the temple. Some of the sanctuaries have erotic statuettes both on the outside of the inner wall. A small amount of the carvings contain sexual themes and those seemingly do not depict deities but rather sexual activities between human individuals. The rest depict the everyday life. These carvings are possibly tantric sexual practices.[92]

Another perspective of these carvings is presented by James McConnachie in his history of the Kamasutra.[93] McConnachie describes the zesty 10% of the Khajuraho sculptures as "the apogee of erotic art":

Twisting, broad-hipped and high breasted nymphs display their generously contoured and bejewelled bodies on exquisitely worked exterior wall panels. These fleshy apsaras run riot across the surface of the stone, putting on make-up, washing their hair, playing games, dancing, and endlessly knotting and unknotting their girdles....Beside the heavenly nymphs are serried ranks of griffins, guardian deities and, most notoriously, extravagantly interlocked maithunas, or lovemaking couples.

In the modern era, erotic photographs are normally taken for commercial purposes. They include mass-produced items such as decorative calendars and pinups. Many of them may also be found in men's magazines, such as Penthouse and Playboy.[94]

Informational or educational

edit-

Two spacecraft Pioneer 10 (launched March 2, 1972) and 11 (launched April 5, 1973) each carried a pioneer plaque metal sheet with a "message of peace" and information about humanity for any potential intelligent extraterrestrial life that might encounter them.[95][96]

-

The Education of Cupid (1527) by Antonio da Correggio. This painting does not depict a Greek myth but rather reflects a growing interest in classical scholarship during the Renaissance.[97]

Studies of the human body

edit-

Anatomical study from De humani corporis fabrica (1543) by Andreas Vesalius

-

An image from A Handbook of Anatomy for Art Students (1896) by Arthur Thompson for art students

-

Young artists studying sculpture in Tel Aviv, 1946

In art, a study is a drawing, sketch or painting done in preparation for a finished piece, or as visual notes.[98] Painting and drawing studies (life-drawing, sketching and anatomy) were part of the artist's education.

Studies are used by artists to understand the problems involved in execution of the artists subjects and the disposition of the elements of the artist work, such as the human body depicted using light, color, form, perspective and composition.[99] Studies can be traced back as long ago as the Italian Renaissance, for example Leonardo da Vinci's and Michelangelo's studies. Anatomical studies of the human body were also executed by medical doctors. The anatomical studies of physician Andreas Vesalius titled De humani corporis fabrica (On the fabric of the human body), published 1543, was a pioneering work of human anatomy illustrated by Titian's pupil Jan Stephen van Calcar.

The Fabrica emphasized the priority of dissection and what has come to be called the "anatomical" view of the body, seeing human internal functioning as an essentially corporeal structure filled with organs arranged in three-dimensional space. In this work, Vesalius also becomes the first person to describe mechanical ventilation.[100] It is largely this achievement that has resulted in Vesalius being incorporated into the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists college arms and crest. Sketching is generally a prescribed part of the studies of art students, who need to develop their ability to quickly record impressions through sketching, from a live model.[101] The sketch is a rapidly executed freehand drawing that is not usually intended as a finished work.[102] The sketch may serve a number of purposes: it might record something that the artist sees, it might record or develop an idea for later use or it might be used as a quick way of graphically demonstrating an image, idea or principle.[101] A sketch usually implies a quick and loosely drawn work, while related terms such as study, and "preparatory drawing" usually refer to more finished drawings to be used for a final work. Most visual artists use, to a greater or lesser degree, the sketch as a method of recording or working out ideas. The sketchbooks of some individual artists have become very well known,[102] including those of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Edgar Degas which have become art objects in their own right, with many pages showing finished studies as well as sketches.[103]

Biology and sexual education

editDepictions of the human body, some of which explicitly nude, may be found in books in the context of human biology,[104] growth and development (especially during puberty),[105][106][107] human sexuality,[108] and sex education,[109] as appropriate for the age of the intended students. Nude photographs and illustrations are also found in sex manuals.[110][111]

Ethnographic photography

editWhat is generally called "ethnographic" nudity has appeared both in serious research works on ethnography and anthropology, as well as in commercial documentaries and in the National Geographic magazine in the United States. In some cases, media outlets may show nudity that occurs in a "natural" or spontaneous setting in news programs or documentaries, while blurring out or censoring the nudity in a dramatic work.[112] The ethnographic focus provided an exceptional framework for photographers to depict peoples whose nudity was, or still is, acceptable within the mores, or within certain specific settings, of their traditional culture.[113][114][115]

Detractors of ethnographic nudity often dismiss it as merely the colonial gaze preserved in the guise of scientific documentation. However, the works of some ethnographic painters and photographers including Herb Ritts, David LaChappelle, Bruce Weber, Irving Penn, Casimir Zagourski, Hugo Bernatzik and Leni Riefenstahl, have received worldwide acclaim for preserving a record of the mores of what are perceived as "paradises" threatened by the onslaught of average modernity.[116]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Hollander, Anne (1978). Seeing Through Clothes. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0140110844.

- ^ a b Eck, Beth A. (December 2001). "Nudity and Framing: Classifying Art, Pornography, Information, and Ambiguity". Sociological Forum. 16 (4). Springer: 603–632. doi:10.1023/A:1012862311849. JSTOR 684826. S2CID 143370129.

- ^ a b Cline, Diane Harris (2016). "Chapter III: Bright, Shining Moment". The Greeks: An Illustrated History. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. pp. 164–5. ISBN 978-1-4262-1670-1.

- ^ a b Spivey, Nigel (2013). "8. Revealing Aphrodite". Greek Sculpture. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. doi:10.1017/9780521760317.010. ISBN 9781316179628. S2CID 239158305.

- ^ Maurice Brock, Bronzino (Paris: Flammarion; London: Thames & Hudson, 2002).

- ^ Deborah, Parker, Bronzino: Renaissance Painter as Poet (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

- ^ Licht, Fred (1979). Goya, the origins of the modern temper in art. New York: Universe Books. p. 83. ISBN 0-87663-294-0.

- ^ Impelluso, Lucia (2003). "Introduction". In Zuffi, Stefano (ed.). Gods and Heroes in Art. Translated by Hartmann, Thomas Michael. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. ISBN 0-89236-702-4.

- ^ "Art Then and Now: Henry Scott Tuke". May 3, 2016. Archived from the original on April 16, 2017. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Mary (1996). "Sexualizing Children: Thoughts on Sally Mann". Salmagundi (111). Skidmore College: 144–145. JSTOR 40535995.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (May 1998). "Photo flap". Reason. Archived from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ "Obscenity Case Is Settled". The New York Times. May 19, 1998. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ "Panel Rejects Pornography Case". The New York Times. September 15, 1991. Archived from the original on November 14, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Kincaid, James R. (January 31, 2000). "Is this child pornography?". Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Powell, Lynn (2010). Framing Innocence: A Mother's Photographs, a Prosecutor's Zeal, and a Small Town's Response. The New Press. ISBN 978-1595585516.

- ^ Akil, Hatem N. (2016). "Colonial Gaze: Native Bodies". In Akil, Hatem N. (ed.). The Visual Divide between Islam and the West: Image Perception within Cross-Cultural Contexts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. pp. 57–86. ISBN 978-1-137-56582-2. Archived from the original on June 10, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1956). "Chapter 1: The Naked and the Nude". The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01788-3.

- ^ Rosenthal, Karin. "About My Work". Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Schiesser, Jody. "Silverbeauty – Artist Statement". Archived from the original on May 25, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ Mok, Marcus. "Artist's Statement". Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved December 11, 2012.

- ^ "Naked before the Camera". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ Weiermair, Peter; Nielander, Claus (1988). Hidden File: Photographs of the Male Nude in the 19th and 20th Centuries. MIT Press, 1988. ISBN 0262231379.

- ^ "Nude Photography Guide". January 30, 2020. Archived from the original on August 1, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2020. Monday, June 29, 2020

- ^ Hudovernik, Robert. Age Beauties: The Lost Collection of Ziegfeld Photographer Alfred Cheney Johnston. New York, NY: Universe Publishing/Rizzoli International Publications, 2006, HB, 272pp.

- ^ "Dazzledent: Fernande Barrey; tumblr". Archived from the original on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 1, 2013.

- ^ Miss Fernande; Comcast.net Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ariadne Asleep On The Island Of Naxos". New-York Historical Society. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b "Victorian nymphs painting back on display after censorship row". BBC News. February 2, 2018. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Yoder, Brian K. "Nudity in Art: A Virtue or Vice?". Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- ^ Vock, Ido (December 12, 2023). "Nude painting row at French school sparks teacher walkout". BBC News. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ Ghiglione, Davide (March 27, 2023). "Italian art experts astonished by David statue uproar in Florida". BBC News. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ Fortin, Jacey (February 5, 2018). "Gallery Wanted to Provoke Debate by Removing Naked Nymphs Painting. It Succeeded". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 2, 2024. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Calogero, R. M. (2004). "A Test Of Objectification Theory: The Effect Of The Male Gaze On Appearance Concerns In College Women". Psychology of Women Quarterly. 28: 16–21. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00118.x. S2CID 144979328.

- ^ Steiner, Wendy (2001). Venus in Exile: The Rejection of Beauty in Twentieth-century Art. The Free Press. pp. 44, 49–50. ISBN 0-684-85781-2.

- ^ Dijkstra, Bram (2010). "Introduction". Naked: The Nude in America. New York: Rizzoli. ISBN 978-0-8478-3366-5.

- ^ Clark, Kenneth (1956). The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form. Princeton University Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 0-691-01788-3.

- ^ Borzello, Frances (2012). "Introduction". The Naked Nude. New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-23892-9.

- ^ Renwick, William Lindsay (1889). The Rise of the Romantics 1789–1815: Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Jane Austen. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990, c1963 ISBN 978-0-1981-2237-1

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (April 1, 2005). "Cry freedom". The Guardian. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

It is the definitive image of the French Revolution - and yet Eugène Delacroix's Liberty Leading the People does not portray the French Revolution at all...This scene, it tells us, took place on July 28 1830.

- ^ Marilyn, Yalom (1997). A history of the breast. Random House. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-679-43459-7.

as in Delacroix's famous painting Liberty Leading the People, which was not about the revolution of 1789, as most people assume, but the bloody uprising of 1830

- ^ Warner, Marina (2000). Monuments & Maidens: The Allegory of the Female Form. University of California Press. pp. 270–71. ISBN 978-0-5202-2733-0.

- ^ Malloy, Judy Powers. "Hiram Powers (1805–1873): Vermont-born Irish American Sculptor, who Lived and Worked in Florence, Italy".

- ^ a b "Hiram Powers". Encyclopædia Britannica. July 7, 2013.

- ^ Wagenknecht, Edward. James Russell Lowell: Portrait of a Many-Sided Man. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971: 138.

- ^ "An Abolitionist Symbol: Hiram Powers's "Greek Slave"". May 2021.

- ^ McMillen, Sally Gregory (2008). Seneca Falls and the origins of the women's rights movement. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-518265-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Lessing, Lauren (2010). "Ties that Bind: Hiram Powers' "Greek Slave" and Nineteenth-Century Marriage". American Art. 24 (1). Smithsonian Institution: 41–65. doi:10.1086/652743. S2CID 192211314.

- ^ Jessica Dawn Blair, et al., "Ethics in advertising: sex sells, but should it?." Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues 9.1/2 (2006): 109+.

- ^ Reichert, Tom (2002). "Sex in advertising research: A review of content, effects, and functions of sexual information in consumer advertising". Annu. Rev. Sex Res. 13: 241–73. PMID 12836733.

- ^ Biswas (1992). "A comparison of print advertisements from the United States and France". Journal of Advertising. 21 (4): 73–81. doi:10.1080/00913367.1992.10673387.

- ^ "Internet Ads with Sexual Imagery at a Critical Level: Survey | Be Korea-savvy". koreabizwire.com. September 8, 2016. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ^ "Nose Art – The Most Unique Art by Pilots During WWII". DailyArt Magazine. February 8, 2022. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- ^ Military Airplanes Get New Gender-neutral Look, Steve Fide, Deseret News, July 19, 1993.

- ^ a b "Aircraft Nose Art Makes Quiet Comeback, Reviving Air Force Tradition". Military.com. October 31, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "Which is the best charity nude calendar in the country?". The Tab. November 27, 2015. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ Gorst, Paul (December 11, 2015). "Oxford's calendar girls beaten 52–0 by Cambridge in women's Varsity rugby match". Mirror Online.

- ^ Lewis, Samantha (July 30, 2023). "Women's World Cup: Inside the infamous nude calendar that got the Matildas in trouble with the Australian government". ABC News (Australia). Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- ^ "HUGE ROW: Foreign press publishes calendar with "alleged Romanian Orthodox Priests in undignified poses"". Bucharest Herald. January 1, 2013. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved June 1, 2022.

- ^ Winston, Kimberly (January 16, 2014). "Racy Orthodox Calendar pushes gay rights ahead of Russian Olympics". Washington Post. Religion News Service.

- ^ "The Pirelli Calendar Overview". Pirelli. June 29, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ McIntosh, Steven (November 29, 2017). "How the Pirelli calendar went from pin-up to political". BBC. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Vanessa (July 26, 2018). "The Pirelli Calendar Finally Makes Women Subjects Instead of Objects". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 4, 2024. Retrieved July 28, 2018.

- ^ The Swedish Film Database: Hon dansade en sommar (1951) – Kommentar Svensk filmografi (in Swedish) Linked 1 March 2014

- ^ IMDb: One Summer of Happiness (1951) – Release info Linked 1 March 2014

- ^ "Protested Film Approved Here". San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco. January 4, 1954. p. 29. Archived from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved January 30, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

The picture has been showing locally at the Sacramento Street international showhouse since mid-October.

- ^ "Ulla Jacobsson, 53, Actress In 'Summer of Happiness'". The New York Times. August 25, 1982.

- ^ Black, Gregory D. (January 26, 1996). Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies (Cambridge Studies in the History of Mass Communication). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56592-8.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (July 11, 1980). "Depth Defying". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ "La Belle Noiseuse (1991)". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Manger, Warren (April 13, 2014). "Kate Winslet: Nude Titanic portrait still haunts me and I always refuse to autograph a copy of it". The Daily Mirror. MGN Limited. Archived from the original on November 7, 2024. Retrieved October 16, 2018.

- ^ "Gender Neutral Bathrooms". October 29, 2014.

- ^ "Starship Troopers-Trivia". IMDb.

The base that houses the Fleet Academy is named 'Tereshkova' after Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. There are many more examples in the movie of the future being gender-neutral (meaning there is no bigotry based on gender), such as the mixed-shower scene and the female captain.

- ^ a b c McGuire, Nneka (January 30, 2020). "Wonder why you see more naked women than men on-screen? Maybe you're asking the wrong question". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c Rose, Steve (January 10, 2023). "'My first day was a sex scene': the disturbing history of teen actors and nudity". The Guardian. Retrieved July 7, 2023.

- ^ Lacey, Liam (March 2, 2012). "The naked truth about on-screen nudity". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Stern, Marlow (July 11, 2017). "The Stars of 'Blue is the Warmest Color' On the Riveting Lesbian Love Story". Daily Beast. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ "Actors advised to set nudity boundaries before filming". BBC News. April 9, 2021. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ Peng, Hsiao-yen; Dilley, Whitney Crothers (2014). From Eileen Chang to Ang Lee: Lust/Caution. Taylor & Francis. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-317-91102-9.

- ^ Chang, Hsiao-hung (2014). Transnational Affect: Cold Anger, Hot Tears, and Lust/Caution. New York: Routledge. pp. 182–196. ISBN 978-0-415-73120-1.

- ^ Lee, Leo Ou-fan (November 2007). "Lust, Caution: Vision and revision". Muse Magazine (10): 96. ISBN 9780307387448.

- ^ "China Yearly Box Office (2007)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 16, 2008.

- ^ "Is Nudity Still a Box-Office Draw?". The Chosun Ilbo. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Elysa, Gardner (July 13, 2003). "Music videos provocatively skirt the nudity issue". USA Today. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2009.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen (December 3, 1990). "Critic's Notebook; That Madonna Video: Realities and Fantasies". New York Times. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ "Top 10 Nude Magazine Covers". Time. 2012. Archived from the original on February 28, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ "Lake Bell Naked for New York Magazine". August 11, 2013. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "Stars' Naked Magazine Covers". E! Online. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ Rawson, Phillip S. (1968). Erotic art of the east; the sexual theme in oriental painting and sculpture. New York: Putnam. p. 380. LCC N7260.R35.

- ^ Clarke, John R. (April 2003). Roman Sex: 100 B.C. to A.D. 250. New York: Harry N. Abrams. p. 168. ISBN 0-8109-4263-1.

- ^ a b Kielletyt kuvat: vanhaa eroottista taidetta Japanista / Förbjudna bilder: gammal erotisk konst från Japan / Forbidden Images – Erotic art from Japan's Edo Period. Helsingin kaupungin taidemuseon julkaisuja. Vol. 75. Helsinki, Finland: Helsinki City Art Museum. 2002. pp. 23–28. ISBN 951-8965-53-6.

- ^ Kornicki, Peter F. (2001). The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 331–53. ISBN 0-8248-2337-0.

- ^ Chopra, Rajesh. "This is a typical erotic posture from Khajuraho Gallery 9". www.liveindia.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2013. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "Kamasutra Book PDF". planetreports.blogspot.in. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ Bayley, Stephen. "A Brief History of Erotic Photography". Sotheby's. Sotheby's Auction House. Retrieved July 18, 2020.

- ^ Rosenthal, Jake (January 20, 2016). "The Pioneer Plaque: Science as a Universal Language". Planetary.com. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Sagan, Carl; Sagan, Linda Salzman; Drake, Frank (1972). "A Message from Earth". Science. 175 (4024): 881–884. doi:10.1126/science.175.4024.881.

- ^ Impelluso, Lucia (2003). Zuffi, Stefano (ed.). Gods and Heroes in Art. Translated by Hartmann, Thomas Michael. Los Angeles, CA: Getty Publications. p. 67. ISBN 0-89236-702-4.

- ^ Gurney, James. "James Gurney Interview". Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- ^ Adams, Steven (1994). The Barbizon School & the Origins of Impressionism. London: Phaidon Press. pp. 31–32, 103. ISBN 0-7418-2919-3.

- ^ Vallejo-Manzur, F.; et al. (2003). "The resuscitation greats. Andreas Vesalius, the concept of an artificial airway". Resuscitation. 56 (1): 3–7. doi:10.1016/S0300-9572(02)00346-5. PMID 12505731.

- ^ a b Cf. Sue Bleiweiss, The Sketchbook Challenge, Potter Craft, 2012, pp. 10–13.

- ^ a b Diana Davies (editor), Harrap's Illustrated Dictionary of Art and Artists, Harrap Books Limited, (1990) ISBN 0-245-54692-8

- ^ Cf. Richard Brereton, Sketchbooks: The Hidden Art of Designers, Illustrators & Creatives, Laurence King, repr. ed. 2012.

- ^ Sadava, David; Heller, H. Craig; Orians, Gordon H.; Purves, William K.; Hillies, David M. (2008). "42: Animal Reproduction". Life: The Science of Biology (8th ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7167-7671-0.

- ^ Bailey, Jacqui (2004). Sex, Puberty, and All that Stuff: A Guide to Growing Up. New York: Barron's. ISBN 0-7641-2992-9.

- ^ Payne, Karen; Antrobus, Laverne; Day, Teresa; Livingstone, Sonia; Modgil, Radha; Pawlewski, Sarah; Winston, Robert (2017). Help Your Kids with Adolescence: A No-nonsense Guide to Puberty and the Teenage Years. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 978-1-4654-6184-1.

- ^ Harris, Robie H.; Emberley, Michael (2014). It's Perfectly Normal: Changing Bodies, Growing Up, Sex, and Sexual Health (4th ed.). Somerville, Massachusetts: Candlewick Press. ISBN 978-0-7636-6872-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Brenot, Philippe; Coryn, Laetitia (2017). The Story of Sex: A Graphic History through the Ages. Translated by McMorran, Will. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-316-47222-7.

- ^ Ann-Marlene, Henning; Olszewski, Tina Bremer; Shin, Heji (2012). Sex & Lovers: A Practical Guide. Cameron & Hollis. ISBN 978-0-906-50628-8.

- ^ Comfort, Alex; Quilliam, Susan (2009). The Joy of Sex: The Ultimate Revised Edition. Harmony. ISBN 978-0-30758-778-7.

- ^ Joannides, Paul; Gross, Daerick (2022). Guide To Getting It On (10th ed.). Goofy Foot Press. ISBN 978-1-88553-504-7.

- ^ "Become an Ethnographic Photographer". Archived from the original on October 31, 2012.

- ^ "Casimir Zagourski "L'Afrique Qui Disparait" (Disappearing Africa)". Library.yale.edu. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ Mlauzi, Linje M. "Reading Modern Ethnographic Photography". Archived from the original on December 24, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2012.

- ^ "Fresh Blood Anyone ? Breakfast with the Suris of Surma in Ethiopia. | PhotoSafari". September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

- ^ "Artist – Hugo Bernatzik". Michael Hoppen Gallery. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

Further reading

edit- Cordwell, Justine M.; Schwarz, Ronald A., eds. (1973). The Fabrics of Culture: the Anthropology of Clothing and Adornment. Chicago: International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences.