Charles Harpur (23 January 1813 – 10 June 1868) was an Australian poet and playwright. He is regarded as "Australia's most important nineteenth-century poet."[1]

Charles Harpur | |

|---|---|

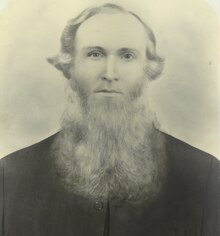

Portrait of Charles Harpur, c. 1860 | |

| Born | Charles Harpur 23 January 1813 Windsor, New South Wales |

| Died | 10 June 1868 (aged 55) Eurobodalla, New South Wales |

| Occupation | teacher, farmer, writer |

| Nationality | Australian |

| Notable works | "The Creek of the Four Graves", "A Mid-Summer Noon in the Australian Forest" |

Life

editEarly life on the Hawkesbury

editHarpur was born on 23 January 1813 at Windsor, New South Wales.[2][3] His parents were convicts. His father, Joseph Harpur, was originally from Kinsale, County Cork, Ireland. He had been sentenced to transportation for highway robbery in March 1800; at the time of Harpur's birth, he was parish clerk and master of the Windsor district school.[4] His mother, Sarah Chidley, was originally from Somerset, and had been sentenced to transportation in 1805.[4][3] Harpur presumably went to school in Windsor, but little information about his education is available. Later in life, he claimed that he taught himself the principles of English verse by obsessively reading William Shakespeare.[5]

Sydney and first publications

editIn the early 1830s, Harpur seems to have moved between Sydney and the Hunter Valley, but by 1833 he had settled with his parents in Sydney.[6] At this time he began to publish his writings in newspapers. His earliest known publications were the poems 'An Australian Song' and 'At the Grave of Clements', which appeared in The Currency Lad on the 4th and 11 May 1833.[7][8] In February 1835 he published parts of his first play, The Tragedy of Donohoe, in The Sydney Monitor, a radical newspaper edited by Edward Smith Hall.[9] Harpur would continue to publish in newspapers throughout his life, eventually publishing hundreds of works in this manner.[10]

In Sydney, Harpur worked as a clerk and letter-sorter in the Post Office,[11] while pursuing a career in the theatre.[12][13] He acted in three plays at the Theatre Royal in October 1833: The Mutiny at the Nore by Douglas Jerrold, The Miller and His Men by Isaac Pocock, and The Tragedy of Chrononhotonthologos, a farce.[13] His acting career ended ignominiously, when he unsuccessfully sued Barnett Levey, the proprietor of the Theatre Royal, for unpaid wages.[14][15] His career at the Post Office ended equally poorly, after he quarrelled with the Postmaster-General.[16]

During these years, Harpur befriended many of Sydney's prominent literary and political figures, including Henry Parkes, Daniel Deniehy, and W. A. Duncan.[17] Looking back at the end of his life, Parkes traced the development of his radical politics back to this circle of friends:[18]

I had now formed the acquaintance of two men of more than ordinary character and ability, Mr. Charles Harpur, one of the most genuine of Australian poets, and Mr. William Augustine Duncan, then proprietor and editor of the 'Weekly Register.' They were my chief advisers in matters of intellectual resource and enquiry, when the prospect before me was opening and widening, often with many cross lights and drifting clouds, but ever with deepening radiance.[19]

Farming in the Hunter Valley

editHarpur had left Sydney two years before and was farming with a brother on the Hunter River. In 1850, he married Mary Doyle and engaged in sheep farming for some years with varying success.[3]

Move to Eurobodalla and death

editIn 1858, he was appointed gold commissioner at Araluen with a good salary. He held the position for eight years and also had a farm at Eurobodalla. Harpur found, however, that his duties prevented him from supervising the work on the farm and it became a bad investment.

Two verse pamphlets, A Poet's Home and The Tower of a Dream, appeared in 1862 and 1865 respectively.[10]

In 1866, Harpur's position was abolished at a time of retrenchment, and in March 1867 he had a great sorrow when his second son was killed by the accidental discharge of his own gun. Harpur never recovered from the blow. He contracted tuberculosis in the hard winter of 1867, and died on 10 June 1868. He was buried on his property, "Euroma", beside the grave of his son.[20][21] He was survived by his wife, two sons and two daughters.[3] One of his daughters, writing many years later, mentioned that he had left his family an unencumbered farm and a well-furnished comfortable home.[22]

In 1988, as part of Australia's bicentennial celebrations, a plaque was laid at the site of Harpur's grave (36°08′21″S 149°58′52″E / 36.139122°S 149.981022°E), describing him as "Australia’s first native born poet".[21]

Work

editTextual history

editHarpur continually revised, redrafted and republished his works throughout his life, creating an "editorial nightmare".[23] In all he is credited with over 700 poems, which exist in some 2,700 distinct versions.[10][24] His major play, The Tragedy of Donohoe, exists in four distinct versions, with different titles, plots and names for the characters.[25] Many of his works exist only in manuscript, or lie scattered among dozens of newspapers and journals. In the past, this hindered research into Harpur's work, because only a small portion was available in reliable and accessible texts.[26][27] In the twentieth century, however, editors such as Charles Salier, Elizabeth Perkins and Michael Ackland greatly improved the situation, by publishing wide selections of Harpur's poetry in book form.[28] In the twenty-first century, Paul Eggert embarked on an ambitious project to make every version of every Harpur poem available online, along with tools to examine Harpur's complex process of rewriting. The fruit of this project was the Charles Harpur Critical Archive, the first variorum edition of Harpur's poetry.[29]

Description of the bush

edit... [T]he Poet, in picturing nature, should never pin himself to the particular, or to the locally present. ... [H]e should paint her primarily through his imagination; and thus the striking features and colors of many scenes, which lie permanently gathered in his memory, becoming, with their influences, idealised in the process, will be essentially transfused up a few, or even upon one scene—one happy embodiment of her wildest freaks, or one Eden-piece embathed with a luminous atmosphere of sentiment. ... Thus it is truth sublimated, compressed, epitomised ...

Many of Harpur's poems describe the Australian bush. Scholars have praised the accuracy and variety of his natural descriptions, while also critiquing his tendency to 'gothicise' the Australian landscape.[32][33][34] In 'gothicising' poems such as "The Creek of the Four Graves", Harpur depicts the Australian landscape as dark, strange, wild and exotic. Some scholars argue that this gothic depiction of the Australian landscape implies that Australia was a terra nullius, and that Harpur's poetry therefore supports the expropriation of Aboriginal lands.[33][35] In other poems, however, Harpur presents a more positive view of the Australian bush. In "The Kangaroo Hunt," Harpur invokes an Aboriginal deity as his Muse, while in "Aboriginal Death Song", he makes explicit reference to Aboriginal sovereignty over land within their "borders".[36][37] Observing these different strains in his poetry, some scholars argue that Harpur's nature poetry is ironic; rather than describing nature from his own perspective, Harpur's poetry describes how nature appears from the point of view of different characters.[32][38]

Harpur underpinned his nature poetry with a sophisticated theory of natural description. This theory relied on two central principles.[31] The first principle was personal experience: in his poetry, Harpur describes the Australian bush based on his own observations and interactions with Aboriginal people. He accurately describes the appearance and behaviour of many bird species in his poetry, for example, and refers to animals by their Indigenous names.[39][40] The second principle was "sublimation" or "compression": rather than describing a particular scene, the poet should combine many observations together to give a complete picture of nature at different times.[31] Through such "sublimation" or "compression", the poet could reveal the workings of the human mind, and expose the spirital or divine aspect of the natural world.[41][42]

Bibliography

editBooks

editPamphlets

edit- Songs of Australia (1850)

- A Poet's Home (1862)

Posthumous Editions

edit- Poems (1883)

- Selected Poems of Charles Harpur (1944)

- Rosa: Love Sonnets to Mary Doyle (1948)

- Charles Harpur edited by Donovan Clarke (1963)

- Charles Harpur edited by Adrian Mitchell (1973)

- Early Love Poems (1979)

- The Poetical Works of Charles Harpur edited by Elizabeth Perkins (1984) ISBN 0207147728

- Charles Harpur, Selected Poetry and Prose edited by Michael Ackland (1986) ISBN 9780140075885

- Stalwart the Bushranger, with, The Tragedy of Donohoe edited by Elizabeth Perkins (1987) ISBN 0868191841

- A Storm in the Mountains and Lost in the Bush (2006) ISBN 0977575845

- Charles Harpur Critical Archive edited by Paul Eggert (2019) ISBN 9781743326831

Select individual poems

edit- "Andrew Marvell" (1845)

- "The Beautiful Squatter" (1845)

- "The Creek of the Four Graves" (1845)

- "A Mid-Summer Noon in the Australian Forest" (1851)

- "The Anchor" (1855)

- "A Similitude" (1855)

- "A Storm in the Mountains" (1856)

- "A Coast View" (1857)

- "To My Infant Daughter 'Ada'" (1861)

- "Love" (1907)

- "Words" (1907)

Nature

- The Cloud (1857)

- To an Echo on the Banks of the Hunter (1846)

- On Leaving x x x, after a residence there of several Months.

- The Bush Fire

- The Scenic Part of Poetry

Indigenous Australians

Poetic craft

Politics

- The Great Change (1850)

- The Tree of Liberty (1846)

- Australia, Huzza! (1833)

- A War-Song for the Nineteenth Century (1843)

- This Southern Land of Ours (1855)

- Is Wentworth a Patriot? (1845)

Love

Religion

Teetotalism

Ballads

Epigrams

- To a Girl Who Stole an Apple Tree

- Whatever is, is Right(?)

- The World's Way

- Neither will do

- Finish of Style

- Evasion

- Shortness of Life (1856)

Unusual subjects

References

edit- ^ Jose, Nicholas, ed. (2009). Macquarie PEN anthology of Australian literature. Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-440-7. OCLC 299734439.

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J. (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Normington-Rawling, J (1966). "Harpur, Charles (1813–1868)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 1. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ a b Normington-Rawling, J (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 2–6.

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J. (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Normtington-Rawling, J. (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. p. 35.

- ^ Harpur, Charles. "An Australian Song (h018)". The Charles Harpur Critical Archive. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Harpur, Charles. "The Grave of Clements (h158)". The Charles Harpur Critical Archive. Retrieved 19 November 2022.

- ^ Perkins, Elizabeth (1987). "Introduction". In Perkins, Elizabeth (ed.). Stalwart the bushranger ; with, the tragedy of Donohoe. Sydney: Currency Press in association with Australasian Drama Studies, St. Lucia. pp. xxix–xxxii. ISBN 0-86819-184-1. OCLC 21294844.

- ^ a b c Austlit – works by Charles Harpur

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J. (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Falk, Michael (2020). "Sad Realities: The Romantic Tragedies of Charles Harpur". Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 (23): 203. doi:10.18573/romtext.65. ISSN 1748-0116.

- ^ a b "Contributor | Mr Charles Harpur". Austage: The Australian Live Performance Database. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 40–41.

- ^ "Domestic Intelligence". The Sydney Monitor. Vol. VIII, no. 628. New South Wales, Australia. 18 December 1833. p. 2 (AFTERNOON). Retrieved 20 November 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Perkins, Elizabeth (1984). "Introduction". In Perkins, Elizabeth (ed.). The poetical works of Charles Harpur. London: Angus & Robertson. pp. xiv. ISBN 0-207-14772-8. OCLC 11425658.

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J (1962). Charles Harpur: An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Falk, Michael (2018). "The Endless Forms of Things: Harpur's Radicalism Revisited". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 18 (3): 1. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Parkes, Henry (1892), Fifty years in the making of Australian history, London: Longmans, Green, and Co, p. 8, nla.obj-3578896, retrieved 20 November 2022 – via Trove

- ^ Normington-Rawling, J. (1962). Charles Harpur, An Australian. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. p. 312.

- ^ a b "Charles Harpur". Monument Australia. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ Baldwin, M Araluen (24 August 1929). "Charles Harpur: First Australian-born Poet: A Daughter's memories". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 11. Retrieved 9 January 2021 – via Trove.

- ^ Eggert, Paul (2016). "Charles Harpur: The Editorial Nightmare". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 16 (2). ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Eggert, Paul (2019). The work and the reader in literary studies : scholarly editing and book history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-108-64101-2. OCLC 1119537929.

- ^ Perkins, Elizabeth (1987). "Introduction". In Perkins, Elizabeth (ed.). Stalwart the bushranger ; with, the tragedy of Donohoe. Sydney: Currency Press in association with Australasian Drama Studies, St. Lucia. pp. xvii. ISBN 0-86819-184-1. OCLC 21294844.

- ^ Wright, Judith (1965). Preoccupations in Australian Poetry. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 2.

- ^ Eggert, Paul (2016). "Charles Harpur: The Editorial Nightmare". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 16 (2): 1. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Eggert, Paul (2016). "Charles Harpur: The Editorial Nightmare". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 16 (2): 4–8. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Eggert, Paul, ed. (2019). The Charles Harpur Critical Archive. Sydney University Press. ISBN 9781743326831.

- ^ Harpur, Charles. "The Kangaroo Hunt (h209-af)". The Charles Harpur Critical Archive. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Ackland, Michael (2002). "From Wilderness to Landscape: Charles Harpur's Dialogue with Wordsworth and Antipodean Nature". Victorian Poetry. 40 (1): 24. doi:10.1353/vp.2002.0001. ISSN 1530-7190. S2CID 170165396.

- ^ a b Webby, Elizabeth (2013). "Representations of 'The Bush' in the Poetry of Charles Harpur". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 14 (3): 2.

- ^ a b Van Toorn, Penny (1992). "The terrors of Terra Nullius-. Gothicising and De-Gothicising aboriginality". World Literature Written in English. 32 (2): 87–97. doi:10.1080/17449859208589194. ISSN 0093-1705.

- ^ Smith, Vivian (2009). "Australian colonial poetry, 1788–1888: Claiming the future, restoring the past". In Pierce, Peter (ed.). The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-521-88165-4.

Harpur's nature, landscape and narrative poems, in which he tries to come to terms with the Australian environment, are still his most widely read. Many later writers have focused on the monotony of the Australian landscape, merging their sense of its social and cultural limitations with the sense of the repetitive sameness of the land. Harpur emphasises its picturesque and dramatic qualities, his verse enlivened by a sense of discovery and revelation.

- ^ Falk, Michael (2018). "The Endless Forms of Things: Harpur's Radicalism Revisited". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 18 (3): 9. ISSN 1833-6027.

The notion of terra nullius haunts much of Harpur's poetry, despite his attempts to present indigenous perspectives. There was 'solitude profound' in Australia before the Europeans came, even if birds, dingoes, kangaroos and people were present.

- ^ Ackland, Michael (2002). "From Wilderness to Landscape: Charles Harpur's Dialogue with Wordsworth and Antipodean Nature". Victorian Poetry. 40 (1): 25. doi:10.1353/vp.2002.0001. ISSN 1530-7190. S2CID 170165396.

- ^ Falk, Michael (2018). "The Endless Forms of Things: Harpur's Radicalism Revisited". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 18 (3): 4. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Falk, Michael (2018). "The Endless Forms of Things: Harpur's Radicalism Revisited". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 18 (3): 2–6. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Dixon, Robert (1980). "Charles Harpur and John Gould". Southerly. 40 (3): 315–329. ISSN 0038-3732.

- ^ Webby, Elizabeth (2014). "Representations of 'The Bush' in the Poetry of Charles Harpur". Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature. 14 (3): 4–6. ISSN 1833-6027.

- ^ Ackland, Michael (1984). "God's Sublime Order in Harpur's 'The Creek of the Four Graves'". Australian Literary Studies. 11 (3): 355–370.

- ^ Ackland, Michael (1983). "Charles Harpur's "the bush fire" and "a storm in the mountains": Sublimity, cognition and faith". Southerly. 43 (4): 459–474. ISSN 0038-3732.

External links

edit- The Charles Harpur Critical Archive

- Works by or about Charles Harpur at the Internet Archive

- Works by Charles Harpur at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Bushrangers: A play in five acts at University of Sydney

- Poems at University of Sydney