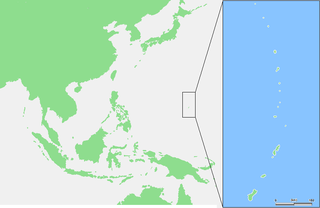

Chamorro (English: /tʃəˈmɔːroʊ/, chə-MOR-oh;[2] endonym: Finuʼ Chamorro [Northern Mariana Islands] or Finoʼ CHamoru [Guam] /t͡saˈmoɾu/)[3] is an Austronesian language spoken by about 58,000 people, numbering about 25,800 on Guam and about 32,200 in the Northern Mariana Islands and elsewhere.[4]

| Chamorro | |

|---|---|

| Finuʼ Chamorro Finoʼ CHamoru | |

| Native to | Mariana Islands |

| Ethnicity | Chamorro |

Native speakers | 58,000 (2005–2015)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ch |

| ISO 639-2 | cha |

| ISO 639-3 | cha |

| Glottolog | cham1312 |

| ELP | Chamorro |

| |

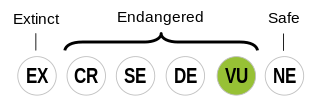

Chamorro is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. | |

It is the historic native language of the Chamorro people, who are indigenous to the Mariana Islands, although it is less commonly spoken today than in the past. Chamorro has three distinct dialects: Guamanian, Rotanese, and that in the other Northern Mariana Islands (NMI).

Classification

editUnlike most of its neighbors, Chamorro is not classified as a Micronesian or Polynesian language. Rather, like Palauan, it possibly constitutes an independent branch of the Malayo-Polynesian language family.[5][6]

At the time the Spanish rule over Guam ended, it was thought that Chamorro was a semi-creole language, with a substantial amount of the vocabulary of Spanish origin and beginning to have a high level of mutual intelligibility with Spanish. It is reported that even in the early 1920s, Spanish was reported to be a living language in Guam for commercial transactions, but the use of Spanish and Chamorro was rapidly declining as a result of English pressure.

Spanish influences in Chamorro exist due to three centuries of Spanish colonial rule. Many words in the Chamorro lexicon are of Latin etymological origin via Spanish, but the pronunciation of these loanwords has been nativized to the phonology of Chamorro, and their use conforms to indigenous grammatical structures. Some authors consider Chamorro a mixed language[7] under a historical point of view, even though it remains independent and unique. In his Chamorro Reference Grammar, Donald M. Topping states:

"The most notable influence on Chamorro language and culture came from the Spanish.... There was wholesale borrowing of Spanish words and phrases into Chamorro, and there was even some borrowing from the Spanish sound system. But this borrowing was linguistically superficial. The bones of the Chamorro language remained intact.... In virtually all cases of borrowing, Spanish words were forced to conform to the Chamorro sound system.... While Spanish may have left a lasting mark on Chamorro vocabulary, as it did on many Philippine and South American languages, it had virtually no effect on Chamorro grammar.... The Japanese influence on Chamorro was much greater than that of German but much less than Spanish. Once again, the linguistic influence was restricted exclusively to vocabulary items, many of which refer to manufactured objects...."[8]

In contrast, in the essays found in Del español al chamorro. Lenguas en contacto en el Pacífico (2009), Rafael Rodríguez-Ponga refers to modern Chamorro as a "mixed language" of "Hispanic-Austronesian" origins and estimates that approximately 50% of the Chamorro lexicon comes from Spanish, whose contribution goes far beyond loanwords.

Rodríguez-Ponga (1995) considers Chamorro to be either Spanish-Austronesian or a Spanish-Austronesian mixed language, or at least a language that has emerged from a process of contact and creolization on the island of Guam since modern Chamorro is influenced in vocabulary and has in its grammar many elements of Spanish origin: verbs, articles, prepositions, numerals, conjunctions, etc.[9]

The process, which began in the 17th century and ended in the early 20th century, meant a profound change from the old Chamorro (paleo-Chamorro) to modern Chamorro (neo-Chamorro) in its grammar, phonology, and vocabulary.[10]

Speakers

editThe Chamorro language is threatened, with a precipitous drop in language fluency over the past century. It is estimated that 75% of the population of Guam was literate in the Chamorro language around the time the United States captured the island during the Spanish–American War[11] (there are no similar language fluency estimates for other areas of the Mariana Islands during this time). A century later, the 2000 U.S. Census showed that fewer than 20% of Chamorros living in Guam speak their heritage language fluently, and the vast majority of those were over the age of 55.

A number of forces have contributed to the steep, post-World War II decline of Chamorro language fluency. There is a long history of colonization of the Marianas, beginning with the Spanish colonization in 1668 and, eventually, the American acquisition of Guam in 1898 (whose hegemony continues to this day). This imposed power structures privileging the language of the region's colonizers. According to estimates, a large majority, as stated above (75%), maintained active knowledge of the Chamorro language even during the Spanish colonial era, but this was all to change with the advent of American imperialism and enforcement of the English language.

In Guam, the language suffered additional suppression when the U.S. government banned the Chamorro language in schools and workplaces in 1922, destroying all Chamorro dictionaries.[12] Similar policies were undertaken by the Japanese government when they controlled the region during World War II. After the war, when Guam was recaptured by the United States, American administrators of the island continued to impose "no Chamorro" restrictions in local schools, teaching only English and disciplining students for speaking their indigenous tongue.[13]

While these oppressive language policies were progressively lifted, Chamorro usage had substantially decreased. Subsequent generations were often raised in households where only the oldest family members were fluent. Lack of exposure made it increasingly difficult to pick up Chamorro as a second language. Within a few generations, English replaced Chamorro as the language of daily life.[citation needed]

There is a difference in the rate of Chamorro language fluency between Guam and the rest of the Marianas. On Guam the number of native Chamorro speakers has dwindled since the mid-1990s. In the Northern Mariana Islands (NMI), younger Chamorros speak the language fluently but prefer English when speaking to their children. Chamorro is common in Chamorro households in the Northern Marianas, but fluency has greatly decreased among Guamanian Chamorros during the years of American rule in favor of the American English commonplace throughout the Marianas.

Today, NMI Chamorros and Guamanian Chamorros disagree strongly on each other's linguistic fluency. An NMI Chamorro would say Guamanian Chamorros speak "broken" Chamorro (i.e., incorrect), whereas a Guamanian Chamorro might consider the form used by NMI Chamorros to be archaic.[citation needed]

Revitalization efforts

editRepresentatives from Guam have unsuccessfully lobbied the United States to take action to promote and protect the language.[citation needed]

In 2013, "Guam will be instituting Public Law 31–45, which increases the teaching of the Chamorro language and culture in Guam schools", extending instruction to include grades 7–10.[14]

Other efforts have been made in recent times, most notably Chamorro immersion schools. One example is Huråo Guåhan Academy at Chamorro Village in downtown Hagåtña. This program is led by Ann Marie Arceo and her husband, Ray. According to the academy's official YouTube page, "Huråo Academy is one if not the first Chamoru Immersion Schools that focus on the teaching of Chamoru language and Self-identity on Guam. Huråo was founded as a non-profit in June 2005."[15] The academy has been praised by many for the continuity of the Chamoru language.

Other creative ways to incorporate and promote the Chamorro language have been found in the use of applications for smartphones, internet videos and television. From Chamorro dictionaries,[16] to the most recent "Speak Chamorro" app,[17] efforts are growing and expanding in ways to preserve and protect the Chamorro language and identity.

On YouTube, a popular Chamorro soap opera Siha[18] has received mostly positive feedback from native Chamorro speakers on its ability to weave dramatics, the Chamorro language, and island culture into an entertaining program. On TV, Nihi! Kids is a first-of-its-kind show, because it is targeted "for Guam's nenis that aims to perpetuate Chamoru language and culture while encouraging environmental stewardship, healthy choices and character development."[19]

In 2019, local news station KUAM News began a series of videos on their YouTube channel, featuring University of Guam's Dr. Michael Bevacqua.[20]

Phonology

editChamorro has 24 phonemes: 18 are consonants and six are vowels.

Vowels

editChamorro has at least 6 vowels, which include:

- /ɑ/, open back unrounded vowel equivalent to the "a" in father.

- /æ/, near-open front unrounded vowel equivalent to the "a" in cat.

- /e/, close-mid front unrounded vowel equivalent to the "e" in the Received Pronunciation of met.

- /i/, close front unrounded vowel equivalent to the "ee" in sleep.

- /o/, close-mid back unrounded vowel equivalent to the "o" in corn.

- /u/, close back rounded vowel equivalent to the "u" in flu.

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | e | o |

| Open | æ | ɑ |

Consonants

editBelow is a chart of Chamorro consonants; all are unaspirated.

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ kʷ ɡʷ | ʔ | |

| Affricate | t̪͡s̪ d̪͡z̪ | ||||

| Fricative | f | s | h | ||

| Rhotic | ɾ~ɻ | ||||

| Approximant | (w) | l |

- /w/ does not occur initially.

- Affricates /t̪͡s̪ d̪͡z̪/ can be realized as palatal [t͡ʃ d͡ʒ] before non-low front vowels.[21]

Historical phonology

editWords containing *-VC_CV- in Proto-Malayo-Polynesian were often syncopated to *-VCCV-. This is most regular for words containing middle *ə (schwa), e.g. *qaləjaw → atdaw "sun", but sometimes also with other vowels, e.g. *qanitu → anti "soul, spirit, ghost". Then after this syncope, older *ə merged with u. Later, *i and *u were lowered to e and o in closed syllables (*demdem → homhom "dark"), or finally but preceded by a closed syllable (*peResi → fokse "squeeze out", but afok "lime" → afuki "put lime on"). The phonemic split between /ɑ/ and /æ/ is still unexplained. Diphthongs *ay and *aw are still retained in Chamorro, while *uy has become i.[22]

| PMP | *p | *t | *c | *k | *q |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chamorro | f | t | s | h ∅ (#_) k |

∅ (#_) ʔ |

| PMP | *b | *d | *z | *j | *R |

| Chamorro | p | h ∅ (_#) |

ch | ʔ | g k (_#) |

| PMP | *l | *h | *w | *y | |

| Chamorro | l t (_#) |

∅ | gw g (_{o, u}) |

y /dz/ |

If a word started with a vowel or *h (but not *q), then prothesis with gw or g (before o or u) occurred: *aku → gwahu "I (emphatic)", *enem → gunum "six". Additionally, *-iaC, *-ua(C), and *-auC have become -iyaC, -ugwa(C), and -agoC respectively.[24]

Grammar

editChamorro is a VSO or verb–subject–object language. However, the word order can be very flexible and change to SVO (subject-verb-object), like English, if necessary to convey different types of relative clauses depending on context and to stress parts of what someone is trying to say or convey. Again, that is subject to debate as those on Guam believe the Chamorro word order is flexible, but those in the NMI do not.

Chamorro is also an agglutinative language, whose grammar allows root words to be modified by a number of affixes. For example, masanganenñaihon 'talked a while (with/to)', passive marking prefix ma-, root verb sangan, referential suffix i 'to' (forced morphophonemically to change to e) with excrescent consonant n, and suffix ñaihon 'a short amount of time'. Thus Masanganenñaihon guiʼ 'He/she was told (something) for a while'.

Chamorro has many Spanish loanwords and other words have Spanish etymological roots (such as tenda 'shop/store' from Spanish tienda), which may lead some to mistakenly conclude that the language is a Spanish creole, but Chamorro very much uses its loanwords in an Austronesian way (bumobola 'playing ball' from bola 'ball, play ball' with verbalizing infix -um- and reduplication of the first syllable of root).

Chamorro is a predicate-initial head-marking language. It has a rich agreement system in the nominal and in the verbal domains.

Chamorro is also known for its wh-agreement in the verb. The agreement morphemes agree with features (roughly the grammatical case feature) of the question phrase and replace the regular subject–verb agreement in transitive realis clauses:[25]

Ha

3sSA

faʼgåsi

wash

si

PND

Juan

Juan

i

the

kareta.

car

'Juan washed the car.'

Håyi

who?

fumaʼgåsi

WH[NOM].wash

i

the

kareta?

car

'Who washed the car?

Pronouns

editThe following set of pronouns is found in Chamorro:[26]

| Free | Absolutive | Agentive | Irrealis nominative | Possessive | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | guåhu | yuʼ | hu | (bai) hu | -hu/-ku* |

| 2nd person singular | hågu | hao | un | un | -mu |

| 3rd person singular | guiya | guiʼ | ha | u | -ña |

| 1st person plural inclusive | hita | hit | ta | (u) ta | -ta |

| 1st person plural exclusive | hami | ham | in | (bai) in | -mami |

| 2nd person plural | hamyu | hamyu | en | en | -miyu |

| 3rd person plural | siha | siha | ma | uha/u/uma | -ñiha |

| * For 1st person singular possessives, the NMI orthography also lists -su and -tu as allomorphs of -hu following words ending in -s and -t, respectively.[27] | |||||

Orthography

edit| Capital | Lowercase | IPA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guam | NMI | ||

| ʼ [a] | /ʔ/ | ||

| A | a | /æ/ | |

| Å | å | /ɑ/ | |

| B[b][c] | b | /b/ | |

| CH[b] | Ch | ch | /ts/ |

| D[b][c] | d | /d/ | |

| E | e | /e/ | |

| F | f | /f/ | |

| G[b][c] | g | /ɡ/ | |

| H[b] | h | /h/ | |

| I | i | /i/ | |

| K | k | /k/ | |

| L[b][c] | l | /l/ | |

| M | m | /m/ | |

| N | n | /n/ | |

| Ñ[b] | ñ | /ɲ/ | |

| NG | Ng | ng | /ŋ/ |

| O | o | /o/ | |

| P | p | /p/ | |

| R[b] | r | /ɾ/ | |

| S | s | /s/ | |

| T | t | /t/ | |

| U | u | /u/ | |

| Y[b] | y | /dz/ | |

The letters ⟨c⟩, ⟨j⟩, ⟨q⟩, ⟨v⟩, ⟨w⟩, ⟨x⟩, ⟨z⟩, ⟨ll⟩, and ⟨rr⟩ are only used in proper names.[28]

In loanwords, some letter combinations in Chamorro sometimes represent single phonemes. For instance, "ci+[vowel]" and "ti+[vowel]" are both pronounced [ʃ], as in hustisia ('justice') and the surname Concepcion (Spanish influence).

The letter ⟨y⟩ is usually (though not always) pronounced more like [dz] (cf. zheísmo in Rioplatense Spanish); it is also sometimes used to represent the same sound as the letter ⟨i⟩ by Guamanian speakers. The phonemes represented by ⟨n⟩ and ⟨ñ⟩ as well as ⟨a⟩ and ⟨å⟩ are not always distinguished in print. Thus the Guamanian place name spelled ⟨Yona⟩ is pronounced ⟨Dzonia⟩ [dzoɲa], not *[jona] as might be expected. ⟨Ch⟩ is usually pronounced like [ts] rather than like English ch. Chamorro ⟨r⟩ is usually a tap /ɾ/, but is rolled /r/ between vowels, and it is a retroflex approximant /ɻ/, like English r, at the beginning of words. Words that begin with r in the Chamorro lexicon are exclusively loanwords.[citation needed]

Chamorro has geminate consonants which are written double ⟨gg⟩, ⟨dd⟩, ⟨kk⟩, ⟨mm⟩, ⟨ngng⟩, ⟨pp⟩, ⟨ss⟩, and ⟨tt⟩. Its native diphthongs are ⟨ai⟩ and ⟨ao⟩, and ⟨oi⟩, ⟨oe⟩, ⟨ia⟩, ⟨iu⟩, and ⟨ie⟩ occur in loanwords. When ⟨i⟩ and another vowel are in hiatus, (i.e., /i.e/, /i.o/, /i.a/, and /i.u/), they are spelled ⟨ihe⟩, ⟨iho⟩, ⟨iha⟩, and ⟨ihu⟩.[28]

The default stress in Chamorro penultimate stress, except where marked otherwise. If marked at all in writing, it is usually with an acute accent, as in asút 'blue' or dángkulu 'big'. Unstressed vowels are limited to /ə i u/, though they are often spelled ⟨a e o⟩. Syllables may end in at most one consonant, as in che’lu 'sibling', diskåtga 'unload', mamåhlåo 'shy', oppop 'lie face down', gåtus (Old Chamorro word for 100), or Hagåtña (capital of Guam).

Chamorro language orthography differs between NMI Chamorros and Guamanian Chamorros (example: NMI Chamorro vs. Guamanian CHamoru). In 2021, Guam's Kumisión I Fino' CHamoru (CHamoru Language Commission) released the Utgrafihan CHamoru as the latest spelling standard for the local dialect and place names.[28] The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands revised their official Chamorro orthography in 2010,[29] which included a version translated into English.[30]

Vocabulary

editNumbers

editCurrent common Chamorro uses only the number words of Spanish origin: uno, dos, tres, etc. Old Chamorro used different number words based on categories: basic numbers (for date, time, etc.), living things, inanimate things, and long objects.

| English | Spanish | Modern Chamorro | Old Chamorro | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Numbers | Living Things | Inanimate Things | Long Objects | |||

| one | uno | unu/una (time) | håcha | maisa | hachiyai | takhachun |

| two | dos | dos | hugua | hugua | hugiyai | takhuguan |

| three | tres | tres | tulu | tatu | toʼgiyai | taktulun |

| four | cuatro | kuåttruʼ | fatfat | fatfat | fatfatai | takfatun |

| five | cinco | singkuʼ | lima | lalima | limiyai | takliman |

| six | seis | sais | gunum | guagunum | gonmiyai | taʼgunum |

| seven | siete | sietti | fiti | fafiti | fitgiyai | takfitun |

| eight | ocho | ochuʼ | guåluʼ | guagualu | guatgiyai | taʼgualun |

| nine | nueve | nuebi | sigua | sasigua | sigiyai | taksiguan |

| ten | diez | dies | månot | maonot | manutai | takmaonton |

| hundred | ciento | siento | gåtus | gåtus | gåtus | gåtus/manapo |

- The number 10 and its multiples up to 90 are dies (10), benti (20), trenta (30), kuårenta (40), sinkuenta (50), sisenta (60), sitenta (70), ochenta (80), nubenta (90). These are similar to the corresponding Spanish terms diez (10), veinte (20), treinta (30), cuarenta (40), cincuenta (50), sesenta (60), setenta (70), ochenta (80), noventa (90).

Days of the week

editCurrent common Chamorro uses only the days of the week which are Spanish in origin but are spelled and pronounced differently. There is currently an effort by Chamorro language advocates to introduce or re-introduce native terms for the Chamorro days of the week. However, both major dialects differ in the terminology used. Guamanian advocates support a number-based system derived from Old Chamorro numerals, whereas the NMI advocates support a more unique system.

| English | Spanish | Contemporary Chamorro | Modern Chamorro (NMI Dialect) | Modern Chamorro (Guamanian Dialect) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunday | Domingo | Damenggo/Damenggu | Gonggat | Hachåni (Day One) | |||

| Monday | Lunes | Lunes/Lunis | Ha'åni (literally means 'day') | Haguåni (Day Two) | |||

| Tuesday | Martes | Måttes/Måttis | Gua'åni | Tulåni (Day Three) | |||

| Wednesday | Miércoles | Métkoles/Metkolis | Tolu'åni | Fatfåni (Day Four) | |||

| Thursday | Jueves | Huebes/Huebis | Fa'guåni | Limåni (Day Five) | |||

| Friday | Viernes | Betnes/Betnis | Nimpu'ak | Gunumåni (Day Six) | |||

| Saturday | Sábado | Såbalu | Sambok | Fitåno (Day Seven) | |||

Months

editBefore the Spanish-based 12-month calendar became predominant, the Chamoru 13-month lunar calendar was commonly used. The first month in the left column below corresponds with January.

| No. | Cunningham[31] | Topping[32] | Kumisión[28] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tumaiguini | Tumaiguini | Tumaiguini |

| 2 | Maimo | Maimo | Maimoʼ |

| 3 | Umatalaf | Umátalaf | Umatålaf |

| 4 | Lumuhu | Lumuhu | Lumuhu |

| 5 | Makmamao | Makmamao | Makmamao |

| 6 | Mananaf or Fananaf | Mananaf | Manånaf |

| 7 | Semo | Semo | Semu |

| 8 | Tenhos | Tenhos | Tenhos |

| 9 | Lumamlam or Lamlam | Lumamlam | Lumåmlam |

| 10 | Fangualoʼ or Faʼgualo | Fagualoʼ | Fangguåloʼ |

| 11 | Sumongsong | Sumongsong | Sumongsong |

| 12 | Umayanggan | Umayangan | Umayanggan |

| 13 | Umagahaf or Omagahaf | --- | Umagåhaf |

| No. | English | Topping[32] | Kumisión[28] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | January | Eneru | Ineru |

| 2 | February | Febreru | Fibreru |

| 3 | March | Matso | Måtso |

| 4 | April | Abrít | Abrit |

| 5 | May | Mayu | Måyu |

| 6 | June | Junio | Hunio |

| 7 | July | Julio | Hulio |

| 8 | August | Agosto | Agosto |

| 9 | September | Septembre | Septiembre |

| 10 | October | Oktubre | Oktubri |

| 11 | November | Nobiembre | Nubiembre |

| 12 | December | Disiembre | Disiembre |

Basic phrases

edit

|

|

|

Studies

editChamorro is studied at the University of Guam, the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa and in several academic institutions of Guam and the Northern Marianas.

Researchers in several countries are studying aspects of Chamorro. In 2009, the Chamorro Linguistics International Network (CHIN) was established in Bremen, Germany. CHiN was founded on the occasion of the Chamorro Day (27 September 2009) which was part of the programme of the Festival of Languages. The foundation ceremony was attended by people from Germany, Guam, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Switzerland, and the United States of America.[33]

References

edit- ^ Chamorro at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ^ "Definition of Chamorro". www.merriam-webster.com. 5 August 2024. Retrieved 1 September 2024.

- ^ "Chamorro Orthography Rules". Guampedia. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Chamorro", Ethnologue (19th ed.), 2016, archived from the original on 5 April 2018, retrieved 4 April 2018

- ^ Blust 2000, pp. 83–122

- ^ Smith, Alexander D. (2017). "The Western Malayo-Polynesian Problem". Oceanic Linguistics. 56 (2): 435–490. doi:10.1353/ol.2017.0021. S2CID 149377092.

- ^ Rodriguez-Ponga, Rafael (2009). Del español al Chamorro: Lenguas en contacto en el Pacífico [From Spanish to Chamorro: Languages in Contact in the Pacific] (in Spanish). Madrid: Ediciones Gondo.

- ^ Topping, Donald (1973). Chamorro Reference Grammar. University Press of Hawaii. pp. 6 and 7. ISBN 978-0-8248-0269-1.

- ^ Rodríguez-Ponga, Rafael (1995). El elemento español en la lengua chamorra (Islas Marianas) [The Spanish element in the Chamorro language (Mariana Islands)] (Doctoral thesis) (in Spanish). Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Facultad de Filología. Archived from the original on 27 June 2010. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ^ Rafael Rodríguez-Ponga, Of Spanish to Chamorro: Language in contact in the Pacific. Madrid, Ediciones Gondo, 2009, www.edicionesgondo.com [1] Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine[2] Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carano, Paul; Sanchez, Pedro (1964). A Complete History of Guam. Tokyo and Rutland, VT: Charles Tuttle Co.

- ^ Skutnabb-Kangas 2000: 206; Mühlhäusler 1996: 109; Benton 1981: 122

- ^ "Education During the US Naval Era". Guampedia. 29 September 2009. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ^ Jones, Michael (29 August 2012). "Guam to Increase Education in Indigenous Language and Culture". Open Equal Free. Education. Development. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 6 September 2012.

- ^ "Hurao Guahan". YouTube. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Sablan, Jerick (19 March 2015). "Apps Help Users Speak, Learn Chamorro". Pacific Daily News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ Martinez, Lacee A. C. (27 March 2014). "Group Produces Chamorro Soap Opera: Siha Can Be Watched on YouTube". Pacific Daily News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- ^ NIHI!, archived from the original on 16 October 2019, retrieved 16 October 2019NIHI!, archived from the original on 16 October 2019, retrieved 16 October 2019

- ^ "Bevacqua: Focus on keeping a language alive; keeping it a living part of the speaking community". Pacific Daily News. 14 April 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2024.

- ^ Chung (1983).

- ^ Blust (2000), p. 88–94.

- ^ Blust (2000), p. 94.

- ^ Blust (2000), p. 97.

- ^ Chung 1998:236 and passim

- ^ Zobel, Erik (2002). "The Position of Chamorro and Palauan in the Austronesian Family Tree: Evidence from Verb Morphosyntax". In Wouk, Fay; Ross, Malcolm (eds.). The History and Typology of Western Austronesian Voice Systems. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 405–434. doi:10.15144/PL-518.405. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ Utugrafihan Finu' Chamorro (PDF). p. 8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Kumisión i Fino’ CHamoru yan i Fina’nå’guen i Historia yan i Lina’la’ i Taotao Tåno’ (September 2020). Utugrafihan CHamoru, Guåhan (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Dipattamentun Kinalamtin Komunidåt yan Kuttura. Uttugrafihan Finu' Chamorro (2010).

- ^ Dipattamentun Kinalamtin Komunidåt yan Kuttura. Chamorro Orthography (2010).

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence J. (1992). Ancient Chamorro Society. Honolulu, Hawaii: The Bess Press. p. 144. ISBN 1-880188-05-8.

- ^ a b Topping, Ogo & Dungca 1975.

- ^ The Maga’låhi (president) is Dr. Rafael Rodríguez-Ponga Salamanca (Madrid, Spain); Maga’låhi ni onrao (honorary president): Dr. Robert A. Underwood (president, University of Guam); Teniente maga’låhi (vice-president): Prof. Dr. Thomas Stolz (Universität Bremen).

Bibliography

edit- Blust, Robert (2000). "Chamorro Historical Phonology". Oceanic Linguistics. 39 (1). University of Hawaii Press: 83–122. doi:10.1353/ol.2000.0002. JSTOR 3623218.

- Chung, Sandra (1983). "Transderivational Relationships in Chamorro Phonology". Language. 59 (1): 35–66. doi:10.2307/414060. JSTOR 414060.

- Chung, Sandra (1998). The Design of Agreement: Evidence from Chamorro. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10607-6.

- Rodríguez-Ponga, Rafael (2003). El elemento español en la lengua chamorra (PhD thesis). Madrid: Complutense University of Madrid. hdl:20.500.14352/63537.

- Rodríguez-Ponga, Rafael (2009). Del español al chamorro. Lenguas en contacto en el Pacífico. Madrid: Ediciones Gondo.

- Topping, Donald M. (1973). Chamorro reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0269-1.

- Topping, Donald M.; Ogo, Pedro M.; Dungca, Bernadita C. (1975). Chamorro-English dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0353-7.

- Topping, Donald M. (1980). Spoken Chamorro: with grammatical notes and glossary (2nd ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0417-6.

Further reading

edit- Aguon, Katherine Bordallo (1995). Chamorro: A Complete Course of Study. Agana, Guam: K.B. Aguon.

- Aguon, Katerine Bordallo (2007). Chamorro: A Complete Course of Study (Revised ed.). K.B. Aguon. ISBN 978-0964841109.

- Chung, Sandra (2020). Chamorro Grammar (PDF). Santa Cruz: University of California. doi:10.48330/E2159R. ISBN 9780578718224.

External links

edit- Chamorro-English Online Dictionary (chamoru.info homepage)

- Webster's Chamorro-English Online Dictionary (archived version)

- Learn Chamoru! CHamoru sentences, videos by Michael Bevacqua.

- Chamorro lessons

- Chamorro Language Lessons (archived version)

- Chamorro/Chamoru – The Language (archived version)

- Chamorro-English dictionary, partially available at Google Books.

- Chamorro Reference Grammar, partially available at Google Books.

- Chamorro Wordlist at the Austronesian Basic Vocabulary Database

- Chamorro Linguistics International Network (CHIN).

- Text and software files from "Chamorro-English Dictionary (PALI Language Texts: Micronesia)" by Donald M. Topping, Pedro M. Ogo, and Bernadita C. Dungca, published in 1975 by University of Hawaii Press archived at Kaipuleohone.

- Index cards of plant and animal names in Chamorro language in Kaipuleohone.