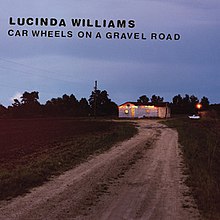

Car Wheels on a Gravel Road is the fifth studio album by American singer-songwriter Lucinda Williams, released on June 30, 1998, by Mercury Records. The album was recorded and co-produced by Williams in Nashville, Tennessee and Canoga Park, California, and features guest appearances by Steve Earle and Emmylou Harris.

| Car Wheels on a Gravel Road | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | June 30, 1998 | |||

| Studio |

| |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 51:40 | |||

| Label | Mercury | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Lucinda Williams chronology | ||||

| ||||

Universally acclaimed by critics, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was voted as the best album of 1998 in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll, and ranked No. 98 on the 2020 revision of Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums of All Time. It won the Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album in 1999, and earned Williams an additional nomination for Best Female Rock Vocal Performance for the single "Can't Let Go". The album peaked at No. 68 on the Billboard 200, and remained on the chart for over five months, eventually becoming Williams' first album to be certified Gold by the RIAA. It remains Williams' best-selling album to date, with 872,000 copies sold in the US alone, as of October 2014. Additionally, it was certified Silver in the UK on July 22, 2013.

Background

editIn 1992, Lucinda Williams released her fourth album, Sweet Old World, on Chameleon Records.[2] To support the album, Williams went on an Australian concert tour with Rosanne Cash and Mary Chapin Carpenter.[2] While on tour, Carpenter recorded a cover of Williams' 1988 song "Passionate Kisses". The cover reached number four on the Hot Country Songs chart and won a Grammy Award for Best Country Song.[2] The popularity of "Passionate Kisses" and subsequent covers of Williams' other songs from musicians like Emmylou Harris and Tom Petty brought Williams a newfound level of attention, and her next album became highly anticipated within the country music scene.[3]

Recording

editThe album was a total clusterfuck.

Chameleon Records folded after the release of Sweet Old World, so Williams signed with American Recordings.[5] The initial recording sessions for Car Wheels on a Gravel Road lasted from February to March 1995 in Austin, Texas, with longtime producer Gurf Morlix.[6] Williams was unhappy with her vocals in these sessions, and decided to start the entire album from scratch.[a] "I was trying to grow. I didn't want to make another Sweet Old World" said Williams.[5] Morlix believes ninety percent of the album was finished when Williams made her decision.[9] Recording sessions resumed later that year in Nashville, Tennessee.[9]

During this period, Williams was invited to sing backing vocals for the Steve Earle song "You're Still Standing There".[5] Earle was working with producer Ray Kennedy, who accentuated Earle's vocals.[5] Williams liked this style of production, and asked Earle and Kennedy to rerecord several of the songs she was unhappy with.[5] Morlix was infuriated by this decision, and resented the two new producers. According to Williams: "Those guys all started vibin' each other, and I'm goin', 'Can we just get this record made, please?"[10] By this point, the relationship between Williams and Morlix was irremediable, and Morlix stepped down as producer.[b] Morlix remained on the project as a guitarist, but was not credited as a producer.[6]

With Earle and Kennedy now serving as full-time producers, the recording sessions recommenced in the summer of 1996 in Nashville.[6] These sessions were recorded on a Telefunken V76 microphone preamplifier connected to a twenty-four track tape recorder.[8] For the first time in Williams' career, she recorded the songs live with her backing band, as opposed to recording each instrument and vocal take individually. Kennedy said: "That's why it became such a great record—because it was so super-charged with her great vocal, which she had never really tried before."[8] Kennedy did not include reverberation, and instead induced compression from a 1176 Peak Limiter.[8] The recording sessions lasted around ten days, after which Kennedy added overdubs.[5] Kennedy overdubbed many of the instruments, including the acoustic and electric guitars, keyboards, tambourines, and backing vocals.[8]

Williams described herself as insecure while recording Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, and was intimidated by Earle's demeanor.[12] Tensions between the two began to emerge towards the end of the sessions, although Earle says this was simply because he knew he would eventually have to go back on tour and leave.[5] In the years after the album's release, Earle was misquoted as saying Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was "the least amount of fun I've had working on a record." Earle believes the misquote likely arose from a radio interview in which he mentioned his frustration at having to leave right before the album was finished. "This is one of the things people think they know what they're talking about. So, that's all there is to that" said Earle.[5]

When Earle left to finish his tour, the majority of the album was finished, although Williams still wanted to add harmonies to some of the songs. Earle was under the impression that once the tour ended, he would return and work on the remaining songs.[5] Instead of waiting for the tour to end, Williams hired musician Roy Bittan, who took the rough mixes to Los Angeles, California.[13] Bittan added organ and accordion instrumentation to eight of the songs, and made separate overdubs to the guitars.[6] Some additional singers were brought in to add backing harmonies, such as Emmylou Harris and Jim Lauderdale.[5] Jim Scott served as the audio mixer, and worked on an AMS Neve console and two Studer tape recorders.[8] Scott took on a minimalist approach to mixing, as he wanted Williams' vocals and guitar to be the most prominent aspect of the album.[8] "So if you're going to play bass, guitar and drums along with her, you're going to play like she sings" said Scott.[8] The process took a couple of weeks, after which it was mastered at MasterMix studios in Nashville, in the midst of the 1998 tornado outbreak.[14]

Music and lyrics

editCar Wheels on a Gravel Road explores a variety of music genres, including country, pop, blues, and folk.[15] Two genres commonly associated with Car Wheels on a Gravel Road are Americana and alternative country, although Williams argues that Americana did not formally exist until the creation of the Americana Music Honors & Awards in 2002.[16] According to Williams: "Before that, there was alternative country and alternative rock. [Americana] was creeping in there already."[5] Andy Greene of Rolling Stone notes that the overall sound of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road differed from the prevailing trend in country music at the time, which was to incorporate more pop influences, as evidenced by the commercial success of Shania Twain's 1997 album Come On Over.[17]

Steve Huey of AllMusic believes that Car Wheels on a Gravel Road features the cleanest production of any album in Williams' career. Huey wrote: "Its surfaces are clean and contemporary, with something in the timbres of the instruments (especially the drums) sounding extremely typical of a late-'90s major-label roots-rock album."[18] Earle and Kennedy's style of production favored mellow grooves for Williams to sing atop, which was greatly influenced by hip hop of the early 1990s.[19] Some songs like "2 Kool 2 Be 4-Gotten" feature hip hop drum beats, and the original version of "Joy" featured a direct-drive turntable.[5] Earle noted the hip hop style of production arose from a desire to experiment.[5]

The lyrics of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road evoke imagery of Williams' life while living in the Deep South.[19] Williams mentions various Southern cities like Jackson, Mississippi and Lafayette, Louisiana, and discusses events that occurred in nondescript locations like backroads and dilapidated shacks.[19] Jenn Pelly of Pitchfork wrote: "Williams was mapping directions home. But home, never fixed to one place, was a profound in-between, more like the breeze that pushed her. Car Wheels is a raw, exquisite travelogue of her American South."[19]

Love and heartbreak are important lyrical themes on Car Wheels on a Gravel Road.[19]

Release

editCar Wheels on a Gravel Road was finished by the summer of 1997, but its release was delayed when Rubin entered negotiations to switch the distribution of American Recordings albums from Warner Bros. Records Inc. to Sony Music Entertainment Inc..[20] This left Williams without a label.[5] Eventually, Williams' manager Frank Callari called Rubin and convinced him to sell the masters to another label.[20] The masters were purchased by Danny Goldberg of Mercury Records for $450,000.[5]

By this point, Williams had been working on Car Wheels on a Gravel Road for nearly three years, and fans were growing impatient.[6] Fans and music journalists blamed the lengthy recording process on Williams' perfectionism, and the album became a running joke on online music forums.[6] In September 1997, The New York Times Magazine published a damning article on Williams, which portrayed her as an incompetent and stubborn musician.[21] This portrayal was strengthened when the article took an out of context quote by Callari, who described her as a "bowl of corn flakes."[6] Williams was dismayed by how the media chose to focus on the behind the scenes issues plaguing the album's release as opposed to the music itself.[6] Some journalists felt the detractions against Williams were sexist, as male artists known for their perfectionism like Bruce Springsteen and John Fogerty did not receive the same negative treatment for lengthy recording sessions.[22]

Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was released by Mercury Records on June 30, 1998.[23] It debuted on the Billboard 200 at number sixty-five, and sold 21,000 copies in its first week.[23]

Critical reception and legacy

edit| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | [18] |

| Chicago Sun-Times | [24] |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[25] |

| The Guardian | [26] |

| Los Angeles Times | [27] |

| NME | 9/10[28] |

| Pitchfork | 9.5/10[19] |

| Rolling Stone | [29] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | [30] |

| The Village Voice | A+[31] |

Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was met with widespread critical acclaim.[2] Reviewing for Entertainment Weekly in July 1998, David Browne found Williams' hard-edged evocations of Southern rural life refreshing amid a music market overrun by timid, mass-produced female artists.[25] Richard Cromelin of the Los Angeles Times said her "resonant, resolute and reassuring" answers to the questions romantic passion and pain pose are as ambitious as the "rich", commanding sound she crafted with producers Steve Earle and Ray Kennedy.[27] NME magazine said Williams transfigures "American roots rock into a heady, soul-baring and, would you believe, unabashedly sexy art form",[28] while Uncut credited the album with "repositioning country-blues roots rock as contemporary Southern art" and offering listeners "a sense of life and place that leap from every line and guitar lick".[32] The Village Voice critic Robert Christgau argued at the time that she proves herself to be the era's "most accomplished record-maker" by honing traditional popular music composition, understated vocal emotions, and realistic narratives colored by her native experiences and values:[33]

Williams's cris de coeur and evocations of rural rootlessness—about juke joints, macho guitarists, alcoholic poets, loved ones locked away in prison, loved ones locked away even more irreparably in the past—are always engaging in themselves. And they mean even more as a whole, demonstrating not that old ways are best, although that meaningless idea may well appeal to her, but that they're very much with us.[34]

At the end of 1998, Car Wheels on a Gravel Road was named one of the year's best albums in many critics' top-ten lists. It topped the annual Pazz & Jop poll and earned Williams a Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Folk Album, although AllMusic's Steve Huey later said it was her "least folk-oriented record".[2]

Car Wheels on a Gravel Road has also been praised in retrospective appraisals. In a five-star review, About.com's Kim Ruehl credited the album with solidifying Williams' status as one of the best singer-songwriters of all time, as she "single-handedly marries the genres of traditional and alternative country, roots rock and American folk music so smoothly, it almost feels like magic."[35] In 2003, Rolling Stone magazine called the record an alternative country masterpiece and ranked it No. 304 on their list of The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time, and ranked it No. 305 in 2012 revised list.[36] In September 2020, Rolling Stone updated its Top 500 albums of all-time list, which reflected an updated and diverse judging pool, and the album rose to No. 98 on that list.[37] In The Rolling Stone Album Guide (2004), David McGee and Milo Miles said it is a masterpiece of timeless quality and greater depth than anything else by Williams, who offers a perfect collection of "faces, fights, keening swamp guitar and sighing accordion, strong drink and stronger lust in an album about places shadowed by memory".[30] The music writers of The Associated Press voted it one of the ten best pop albums of the 1990s.[38] It was also included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die[39] and in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000), in which it was voted No. 836.[40] Christgau later named it among his 10 best albums from the 1990s.[41]

Some journalists have credited Car Wheels on a Gravel Road with popularizing Americana music, and defining parameters that would eventually becomes stapes within the genre.[42] Stephen L. Betts of Rolling Stone wrote: "[Car Wheels on a Gravel Road's] genesis coincides with the birth of the Americana radio format and with masterful nods to country, blues and rock, the finished product, released in June 1998, reflects the cornerstones of that burgeoning movement."[43] Edd Hurt of Nashville Scene gave similar commentary, and said: "Car Wheels, like similar Americana albums of the time (Fight Songs by Old 97's, for instance), defined the genre as a space in which disparate elements of American music could combine to inspire work that only seemed folkish and unstudied."[44]

Track listing

editAll tracks written by Lucinda Williams, except where noted.[45]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Right in Time" | 4:35 | |

| 2. | "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road" | 4:44 | |

| 3. | "2 Kool 2 Be 4-Gotten" | 4:42 | |

| 4. | "Drunken Angel" | 3:20 | |

| 5. | "Concrete and Barbed Wire" | 3:08 | |

| 6. | "Lake Charles" | 5:27 | |

| 7. | "Can't Let Go" | Randy Weeks | 3:28 |

| 8. | "I Lost It" | 3:31 | |

| 9. | "Metal Firecracker" | 3:30 | |

| 10. | "Greenville" | 3:23 | |

| 11. | "Still I Long for Your Kiss" |

| 4:09 |

| 12. | "Joy" | 4:01 | |

| 13. | "Jackson" | 3:42 | |

| Total length: | 51:40 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14. | "Down the Big Road Blues" | Mattie Delaney | 4:07 |

| 15. | "Out of Touch" | 3:50 | |

| 16. | "Still I Long for Your Kiss" (Alternate version) |

| 5:00 |

| Total length: | 64:37 | ||

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Pineola" | 4:18 | |

| 2. | "Something About What Happens When We Talk" | 3:44 | |

| 3. | "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road" | 4:42 | |

| 4. | "Metal Firecracker" | 3:39 | |

| 5. | "Right in Time" | 4:32 | |

| 6. | "Drunken Angel" | 3:27 | |

| 7. | "Greenville" | 3:46 | |

| 8. | "Still I Long for Your Kiss" |

| 4:39 |

| 9. | "2 Kool 2 Be 4-Gotten" | 4:53 | |

| 10. | "Can't Let Go" | Weeks | 3:51 |

| 11. | "Hot Blood" | 7:38 | |

| 12. | "Changed the Locks" | 4:19 | |

| 13. | "Joy" | 6:08 |

Personnel

edit- Lucinda Williams – vocals (all tracks), acoustic guitar (2, 5), Dobro guitar (7)

- Gurf Morlix – electric guitar (1–3, 9, 12), 12-string electric guitar (4), electric slide guitar (7), harmony vocal (9), acoustic slide guitar (13)

- John Ciambotti – bass guitar (1–12), upright bass (13)

- Donald Lindley – drums, percussion (all tracks)

- Buddy Miller – acoustic guitar (1, 10, 11), mando guitar (2, 10), harmony vocal (2), electric guitar (6, 8)

- Ray Kennedy – 12 string electric guitar (1)

- Greg Leisz – 12 string electric guitar (1), mandolin (5)

- Roy Bittan – organ (1, 3, 4), accordion (3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 13)

- Jim Lauderdale – harmony vocal (1, 4, 6, 8, 13)

- Charlie Sexton – electric guitar (3, 8, 10), Dobro guitar (6)

- Steve Earle – acoustic guitar (4, 5, 8, 9, 13), harmonica (4), harmony vocal (5), resonator guitar (12)

- Johnny Lee Schell – electric guitar (4, 7, 11, 12), electric slide guitar (5, 7), Dobro guitar (13)

- Bo Ramsey – electric guitar (7, 12), slide guitar (7)

- Micheal Smotherman – B-3 organ (9)

- Richard "Hombre" Price – Dobro guitar (10)

- Emmylou Harris – harmony vocal (10)

Charts

edit| Chart (1998) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (ARIA)[46] | 69 |

| Canadian Country Albums (RPM)[47] | 14 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[48] | 60 |

| US Billboard 200[49] | 65 |

Certifications

edit| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom (BPI)[50] | Silver | 60,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[51] | Gold | 500,000^ |

|

^ Shipments figures based on certification alone. | ||

Notes

edit- ^ A 1998 article by the Los Angeles Times states that another possible reason these sessions were scrapped was because American Recordings founder Rick Rubin was also unhappy with the vocals.[7] Ray Kennedy supported this claim in a 2020 article published by Mix.[8]

- ^ Some sources claim Williams fired Morlix,[11] although Morlix states he stepped down of his own accord.[9]

Footnotes

edit- ^ Pitchfork Staff (September 28, 2022). "The 150 Best Albums of the 1990s". Pitchfork. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

Lucinda Williams was two decades into her career at the cross-section of country and rock when she finally released her full-length opus...

- ^ a b c d e Huey (a) n.d.

- ^ Huey (a) n.d.; Smith 1998

- ^ Anon. 2019, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Scott 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Anon. 1998a.

- ^ McCall 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Flans 2020.

- ^ a b c Nichols 2000.

- ^ Wilonsky 1998.

- ^ Frey 1997; Jarrett 2014, p. 250

- ^ Scott 2018; Anon. 2019, p. 73

- ^ Anon. 1998a; Scott 2018

- ^ Mundy 1998; Flans 2020

- ^ Verna 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Greene 2018; Scott 2018

- ^ Greene 2018.

- ^ a b Huey (b) n.d.

- ^ a b c d e f Pelly 2018.

- ^ a b Anon. 2019, p. 74.

- ^ Anon. 1998a; Mundy 1998

- ^ Anon. 1998a; McCall 1998

- ^ a b Mayfield 1998, p. 92.

- ^ Houlihan-Skilton 1998.

- ^ a b Browne, David (July 10, 1998). "Dandy Williams: Much delayed and breathlessly awaited, Lucinda's gritty new cycle of songs Wheels so good". Entertainment Weekly. No. 440. New York. p. 74. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- ^ Sweeting, Adam (July 10, 1998). "Lucinda Williams: Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (Mercury)". The Guardian. London.

- ^ a b Cromelin, Richard (August 9, 1998). "Lucinda Williams, 'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road,' Mercury". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Martin, Gavin (July 25, 1998). "Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". NME. London. Archived from the original on August 17, 2000. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- ^ Edwards, Gavin (October 30, 2006). "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (Reissue)". Rolling Stone. New York. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ a b McGee, David; Miles, Milo (2004). "Lucinda Williams". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). London: Fireside Books. pp. 875–876. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Christgau 1998a.

- ^ "Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road CD Album". CD Universe. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ Christgau 1998a; Christgau 1998b

- ^ Christgau 1998b.

- ^ Ruehl, Kim. "Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road, Deluxe Edition". About.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time Rolling Stone's definitive list of the 500 greatest albums of all time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on September 22, 2020. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ^ "Top Albums of the 1990s". Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Dimery, Robert; Lydon, Michael (March 23, 2010). 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die: Revised and Updated Edition. Universe. ISBN 978-0-7893-2074-2.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2006). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 259. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (May 19, 2021). "Xgau Sez: May, 2021". And It Don't Stop. Substack. Archived from the original on May 23, 2021. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Betts 2018; Scott 2018; Hurt 2019

- ^ Betts 2018.

- ^ Hurt 2019.

- ^ Anon. (1998). Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (liner notes). Lucinda Williams. Mercury Records.

- ^ Ryan, Gavin (2011). Australia's Music Charts 1988–2010 (PDF ed.). Mt Martha, Victoria, Australia: Moonlight Publishing. p. 302.

- ^ Anon. (August 31, 1998). "RPM Country Albums". RPM. Vol. 67, no. 23. p. 9. ISSN 0315-5994.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". Hung Medien. Retrieved March 1, 2022.

- ^ "Lucinda Williams Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ "British album certifications – Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". British Phonographic Industry. June 25, 1999. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ^ "American album certifications – Lucinda Williams – Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". Recording Industry Association of America. July 22, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

References

edit- Anon. (August 1, 1998). "Lucinda Williams – Setting the record straight". No Depression. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Anon. (September 2019). "The Making of Car Wheels on a Gravel Road by Lucinda Williams". Uncut. ISSN 1368-0722.

- Betts, Stephen L. (August 20, 2018). "Lucinda Williams Plots 'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road' Anniversary Tour". Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- Christgau, Robert (1998). "Lucinda Williams: Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". Rolling Stone. No. July 23. New York. Archived from the original on March 17, 2015. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- Christgau, Robert (1998). "Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. No. June 30. New York. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- Flans, Robyn (February 2, 2020). "'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road'". Mix. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 23, 2020.

- Frey, Darcy (September 14, 1997). "Lucinda Williams Is in Pain". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Greene, Andy (November 2, 2018). "Lucinda Williams Reflects on 'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road' at 20". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 22, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- Houlihan-Skilton, Mary (July 5, 1998). "Spin Control". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on February 29, 2016. Retrieved September 26, 2015.

- Huey, Steve (n.d.). "Lucinda Williams Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Huey, Steve (n.d.). "Car Wheels on a Gravel Road – Lucinda Williams". AllMusic. Archived from the original on June 5, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2005.

- Hurt, Edd (May 28, 2019). "Lucinda Williams Revisits 1998's Epochal Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". Nashville Scene. Retrieved January 3, 2022.

- Jarrett, Michael (2014). Producing Country: The Inside Story of the Great Recordings. Wesleyan University Press. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8195-7465-7.

- Mayfield, Geoff (July 18, 1998). "Between the Bullets". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 29. ISSN 0006-2510.

- McCall, Michael (August 9, 1998). "Way Off the Fast Track; Lucinda Williams takes her time making music. But with results like 'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road,' her career could shift into high gear". Los Angeles Times. p. 6.

- Mundy, Chris (August 6, 1998). "Lucinda Williams' Home-Grown Masterpiece". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- Nichols, Lee (April 14, 2000). "Out Front". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Pelly, Jenn (October 28, 2018). "Lucinda Williams: Car Wheels on a Gravel Road". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on October 28, 2018. Retrieved October 28, 2018.

- Scott, Jason (June 30, 2018). "'Car Wheels on a Gravel Road' Turns 20: Lucinda Williams & Producer Steve Earle Reflect on Her Masterpiece". Billboard. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Smith, RJ (July 1998). "Lucinda Williams: Lost in America". Spin.

- Verna, Paul (July 18, 1998). "Reviews & previews: Albums". Billboard. Vol. 110, no. 29. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Wilonsky, Robert (December 3, 1998). "Long Journey Home". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

External links

edit- Car Wheels on a Gravel Road at Discogs (list of releases)

- Car Wheels on a Gravel Road (Adobe Flash) at Myspace (streamed copy where licensed)

- Lucinda Williams Official Website