Camp Letterman was an American Civil War military hospital, which was erected near the Gettysburg Battlefield to treat more than 14,000 Union and 6,800 Confederate wounded of the Battle of Gettysburg at the beginning of July 1863.[1][2]

| Camp Letterman eponym: Dr Jonathan Letterman | |

|---|---|

| Part of Army Medical Service | |

| George Wolf farm east of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, near the York Pike | |

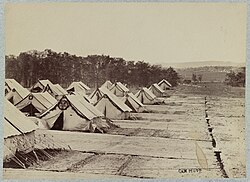

Camp Letterman, August 1863 | |

| Type | Union Army field hospital |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1863 |

| In use | 1863 |

- Not the Letterman Army Hospital of the Presidio of San Francisco

History

editOne of the most important military engagements of the American Civil War, the Battle of Gettysburg was waged over the first three days of July 1863 between the United States' Army of the Potomac, which was commanded by Major-General George Gordon Meade, and the Confederate States of America's Army of Northern Virginia, which had been marched north into Maryland and Pennsylvania by its commanding Major-General Robert E. Lee. Clashing near the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, the conflict quickly escalated into an intense combat situation with multiple, memorable skirmishes and battles, including Seminary Ridge, Little Round Top and Pickett's Charge.[3] Meade's Union troops ultimately won the three-day, tide-turning engagement, which resulted in the deaths of more than 3,100 Union and 4,700 Confederate troops with wounded men totaling more than 14,500 (Union) and 12,600 (Confederate).[4]

In the aftermath, when Union military leaders realized that the farms, private homes, churches, and other buildings in and around the town of Gettysburg which had been pressed into service as makeshift regimental hospitals were so overwhelmed by the numbers of dying and wounded, and that many of the soldiers who had been unable to find shelter were being cared for in gardens and other outdoor spaces, they quickly secured approval from their superiors to create a new general hospital. Built sometime after July 8, 1863,[5] it opened on July 22,[6] and was named Camp Letterman in honor of Jonathan Letterman, M.D., the "Father of Battlefield Medicine" who created medical management procedures which transformed not only Civil War-era medicine, but the medical care for thousands of soldiers in subsequent wars, the tents of the hospital complex were erected east of Gettysburg. Union Army surgeons, nurses and members of the U.S. Sanitary Commission then began rendering care to soldiers from both sides of the conflict, ultimately evaluating and treating all of the wounded who had been transported from the various battle sites around Gettysburg. Meals were prepared for the men by a sizeable force of cooks while guards kept the peace among those who were ambulatory. Those needing more advanced treatment or who were doing well enough to be moved out for convalescent care were subsequently sent on to the Union's larger hospitals in Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C.[7][8]

Henry Janes was the physician in charge of this Union Army hospital.[9]

On 3 October 1863, this hospital's namesake, Dr. Jonathan Letterman, penned a report to his superiors, which provided key details regarding the "operations of the medical department of the Union Army's with respect to the Gettysburg Campaign. Among Letterman's key points:[10]

".... It is scarcely necessary to say that if the transportation [of wounded men] is not sufficient to enable the officers of the department to conduct it properly, the effect must fall upon the wounded.

In the autumn of 1862, I investigated the subject very carefully, with the view to the adoption of some system instead of the irregular method and want of system which prior to that time was in vogue, to limit the amount necessary, and to have that amount always available. The transportation was one wagon to each regiment and one to each brigade.... This system worked well....

On June 19, while the army was on the march … from before Fredericksburg to some unknown point north of the Potomac River, the headquarters being near Fairfax Court-House, Va., the transportation of the department was cut down by Major-General Hooker on an average of two wagons in a brigade, in opposition to my opinion.... This reduction necessitated the turning in of a large portion of the supplies, tents, &c., which were necessary for the proper care of the wounded in the event of a battle. Three wagons were assigned to a brigade of 1,500 men, doing away with regimental wagons. This method in its practical working is no system at all … and proved to be, what I supposed at the time it would be, a failure to give the department the means necessary to conduct its operations.

The headquarters left Fairfax Court-House on June 26 ultimo, for some point as yet unknown in Maryland or Pennsylvania. On the 25th of that month, I directed Assistant Surgeon [Jeremiah B.] Brinton, U.S. Army, to proceed to Washington, and obtain the supplies I had ordered the medical purveyor to have put up....

On the 26th, he was ordered to proceed with them to Frederick. This step was taken to obviate the want of supplies consequent upon the reduction of transportation. At this date it was not known that the army would be near Frederick ... the event justified the order, Dr. Brinton arriving at Frederick on June 28, the day after the arrival of headquarters there, with twenty-five army wagon loads of such supplies as would be most required in case of a battle. The train with these supplies followed that of headquarters until we reached Taneytown.

On July 1 … it was ordered that "corps commanders and the commander of the Artillery Reserve will at once send to the rear all their trains (excepting ammunition wagons and ambulances), parking them between Union Mills and Westminster."

On the 2d, these trains were ordered still farther to the rear, and parked near Westminster, nearly 25 miles distant from the battlefield. The effect of this order was to deprive the department almost wholly of the means for taking care of the wounded until the result of the engagement of the 2d and 3d was fully known.... In most of the corps the wagons exclusively used for medicines moved with the ambulances, so that the medical officers had a sufficient supply of dressings, chloroform, and such articles until the supplies came up, but the tents and other appliances, which are as necessary, were not available until July 5.

The supply of Dr. Brinton reached the field on the evening of July 4. This supply, together with the supplies ordered by me on July 5 and 6, gave more than was required. The reports of Dr. Brinton and Dr. [John H.] Taylor show that I ordered more supplies than were used up to the 18th of July, when the hospitals were taken from under my control. Surgeon Taylor, medical inspector of this army, who was ordered on July 29 to Gettysburg, to examine into the state of affairs there, reports to me that he made "the question of supplies a subject of special inquiry among the medical officers who had remained with the wounded during and for a month subsequent to the battle. The testimony in every instance was conclusive that at no time had there been any deficiency, but, on the contrary, that the supply furnished by the medical purveyor had been and still continued to be abundant." This is, perhaps, sufficient to show that not only were supplies ordered in advance, but that they were on hand when required, notwithstanding the difficulty in consequence of the inability of the railroad to meet the requirements made upon it, until after General Haupt took charge of it on July 9.... The chief want was tents and other appliances for the better care of the wounded. I had an interview with the commanding general on the evening of July 3, after the battle was over, to obtain permission to order up the wagons containing the tents, &c. This request he did not think expedient to grant but in part, allowing one-half the wagons to come to the front; the remainder were brought up as soon as it was considered by him proper to permit it. To show the result of the system adopted upon my recommendation regarding transportation, and the effect of the system of field hospitals, I may here instance the hospital of the Twelfth Corps, in which the transportation was not reduced nor the wagons sent to the rear at Gettysburg.

Surgeon [John] McNulty, medical director of that corps, reports that "it is with extreme satisfaction that I can assure you that it enabled me to remove the wounded from the field, shelter, feed them, and dress their wounds within six hours after the battle ended, and to have every capital operation performed within twenty-four hours after the injury was received. I can, I think, safely say that such would have been the result in other corps had the same facilities been allowed -- a result not to have been surpassed, if equaled, in any battle of magnitude that has ever taken place.

A great difficulty always exists in having food for the wounded. By the exertions of Colonel [Henry F.] Clarke, chief commissary, 30,000 rations were brought up on July 4 and distributed to the hospitals. Some of the hospitals were supplied by the commissaries of the corps to which they belonged. Arrangements were made by him to have supplies in abundance brought to Gettysburg for the wounded; he ordered them, and if the railroad could have transported them they would have been on hand.

Over 650 medical officers are reported as present for duty at that battle. These officers were engaged assiduously, day and night, with little rest, until the 6th, and in the Second Corps until July 7, in attendance upon the wounded. The labor performed by these officers was immense. Some of them fainted from exhaustion, induced by over-exertion, and others became ill from the same cause. The skill and devotion shown by the medical officers of this army were worthy of all commendation; they could not be surpassed. Their conduct as officers and as professional men was admirable. Thirteen of them were wounded, one of whom (Asst. Surg. W. S. Moore, Sixty-first Ohio Volunteers, Eleventh Corps) died on July 6 from the effects of his wounds, received on the 3d. The idea, very prevalent, that medical officers are not exposed to fire, is thus shown to be wholly erroneous. The greater portion of the surgical labor was performed before the army left. The time for primary operations had passed, and what remained to be done was to attend to making the men comfortable, dress their wounds, and perform such secondary operations as from time to time might be necessary. One hundred and six medical officers were left behind when the army left; no more could be left, as it was expected that another battle would within three or four days take place, and in all probability as many wounded thrown upon our hands as at the battle of the 2d and 3d, which had just occurred. No reliance can be placed on surgeons from civil life during or after a battle. They cannot or will not submit to the privations and discomforts which are necessary, and the great majority think more of their own personal comfort than they do of the wounded.... Dr. [Henry] Janes, who was left in charge of the hospitals at Gettysburg, reports that quite a number of surgeons came and volunteered their services, but "they were of little use"....

Dr. Janes was left in general charge of the hospitals, and, to provide against contingencies, was directed, if he could not communicate with me, to do so directly with the Surgeon-General, so that he had full power to call directly upon the Surgeon-General to supply any want that might arise.

The ambulance corps throughout the army acted in the most commendable manner during those days of severe labor. Notwithstanding the great number of wounded, amounting to 14,193, I have it from the most reliable authority and from my own observation that not one wounded man of all that number was left on the field within our lines early on the morning of July 4. A few were found after daylight beyond our farthest pickets, and these were brought in, although the ambulance men were fired upon when engaged in this duty by the enemy, who were within easy range. In addition to this duty, the line of battle was of such a character, resembling somewhat that of a horseshoe, that it became necessary to remove most of the hospitals farther to the rear as the enemy's fire drew nearer.

This corps did not escape unhurt; 1 officer and 4 privates were killed and 17 wounded while in the discharge of their duties. A number of horses were killed and wounded, and some ambulances injured.... I know of no battle-field from which wounded men have been so speedily and so carefully removed, and I have every reason to feel satisfied that their duties could not have been performed better or more fearlessly.

Before the army left Gettysburg, and knowing that the wounded had been brought in from the field, six ambulances and four wagons were ordered to be left from each corps, to convey the wounded from their hospitals to the railroad depot, for transportation to the other hospitals. From the Cavalry Corps but four ambulances were ordered, as this corps had a number captured by the enemy at or near Hanover a few days previous. I was informed by General Ingalls that the railroad to Gettysburg would be in operation on the 6th, and upon this based my action. Had such been the case, this number would have been sufficient. As it proved that this was not in good running order for some time after that date, it would have been better to have left more ambulances. I acted on the best information that could be obtained.

The number of our wounded, from the most reliable information at my command, amounted to 14,193.(*) The number of Confederate wounded who fell into our hands was 6,802, making the total number of wounded thrown by that battle upon this department 20,995. The wounded of July 1 fell into the hands of the enemy, and came under our control on the 4th of that month. Instruments and medical supplies belonging to the First and Eleventh Corps were in some instances taken from the medical officers of those corps by the enemy....

It is unnecessary to do more than make an allusion to the difficulties which surrounded this department at the engagement at Gettysburg. The inadequate amount of transportation; the impossibility of having that allowed brought to the front; the cutting off our communication with Baltimore, first by way of Frederick and then by way of Westminster; the uncertainty, even as late as the morning of July 1, as to a battle taking place at all, and, if it did, at what point it would occur; the total inadequacy of the railroad to Gettysburg to meet the demands made upon it after the battle was over; the excessive rains which fell at that time-- all conspired to render the management of the department one of exceeding difficulty, and yet abundance of medical supplies were on hand at all times; rations were provided, shelter obtained, as soon as the wagons were allowed to come to the front, although not as abundant as necessary on account of the reduced transportation. Medical officers, attendants, ambulances, and wagons left when the army started for Maryland, and the wounded were well taken care of, and especially so when we consider the circumstances under which the battle was fought and the length and severity of the engagement.

The conduct of the medical officers was admirable. Their labors not only began with the beginning of the battle, but lasted long after the battle had ended. When other officers had time to rest, they were busily at work--and not merely at work, but working earnestly and devotedly.

By January 1864, Camp Letterman was no longer needed by the Union Army; so, the facility was closed.[11]

In June 2018, the Pennsylvania House of Representatives voted unanimously to pass House Resolution No. 998 to honor Camp Letterman for the role it played in treating the large number of casualties who had been wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg during July 1863.[12]

The role of women at Camp Letterman

editAccording to accounts by Sophronia Bucklin[13] and Cornelia Hancock,[14] two of the seven women who served at nurses at Camp Letterman following the Battle of Gettysburg, an additional 30-plus women served in capacities other than nursing (making the combined total of women at Camp Letterman roughly 40). According to Hancock, she and three other women were assigned to one of the hospital tents. Per Bucklin, the nurses' accommodations were spartan:[15][16]

"My tent contained an iron bedstead, on which for a while I slept with the bare slats beneath, and covered with sheets and blanket. I afterwards obtained a tick and pillow, from the Sanitary Commission, and filled them with straw, sleeping in comparative comfort. I soon found, however, that the wounded needed these more than I, and back I went to the hard slats again, this time without the sheets, which were given for the purpose of changing a patient’s blood-saturated bed. As time passed, and the heavy rains fell, sending muddy rivulets through our tents, we were often obliged in the morning to use our parasol handles to fish up our shoes from the water before we could dress ourselves. A tent cloth was afterwards put down for a carpet, and a Sibley stove set up to dry our clothing. These were oft times so damp, that it was barely possible to draw on the sleeves of our dresses. By and by I had the additional comfort of two splint-bottomed rocking chairs, which were given me by convalescent patients, who had brought them to the hospital for their own use, and on departing left them a legacy to me. With these a stand was added to my furniture. I here learned how few are nature’s real wants. I learned how much, which at home we call necessary, can be lopped off, and we still be satisfied; how sleep can visit our eyelids, and cold be driven away with the fewest comforts around us."

Another of the seven nurses, Margaret Hamilton, rendered care to patients who were isolated in Letterman's smallpox ward.[17] Tillie Pierce, a teenager at the time of the battle, also reportedly nursed wounded men at Camp Letterman. An eyewitness to troop movements and various stages of the battle, she was the daughter of a Gettysburg butcher, and later went on to write, At Gettysburg, or What A Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle: A True Narrative."[18][19]

One of those who provided other services was Rebecca Lane Pennypacker Price who, as a member of the Phoenixville Union Relief Society, had been involved in relief efforts since the beginning of the war, recruiting women to sew and knit clothing items for Union troops, organizing financial and other types of donation drives, and personally delivering supplies to troops thanks to the help of a travel pass that was issued to her by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin. She then progressed on to provide nursing care at various Union hospitals, where she became acquainted with, and respected by, several military physicians. Initially partnering with members of her relief society and the Christian Commission to collect and transport supplies to Gettysburg following the battle, she quickly became a helper to the Union's ambulance corps, providing comfort to men who were awaiting transport from battle sites, helping to distract those awaiting amputation and other surgical procedures, and writing letters on behalf of dying soldiers who wanted to transmit their final thoughts and to their families. As physicians she knew from previous battlefield assignments came to realize that she was on site at Letterman, she increasingly became involved with caring for hopeless medical cases, rendering end-of-life care to men from both sides of the conflict who were too grievously wounded to survive their injuries.[20]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Musto, R. J (July 2007). "The Treatment of the Wounded at Gettysburg: Jonathan Letterman: The Father of Modern Battlefield Medicine". Gettysburg Magazine (37): 125.

- ^ Atkinson, Matthew. "'War is a hellish way of settling a dispute": Dr. Jonathan Letterman and the Tortuous Path of Medical Care from Manassas to Camp Letterman," pp. 101-113, in "Gettysburg Seminars 2010." Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service and Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Gettysburg National Military Park, 2010.

- ^ "History and Culture," in "Gettysburg National Military Park." Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online August 8, 2019.

- ^ Busey, John W., and David G. Martin. Regimental Strengths and Losses at Gettysburg, 4th ed, pp. 125, 260. Hightstown, New Jersey: Longstreet House, 2005. ISBN 0-944413-67-6.

- ^ Atkinson, "'War is a hellish way of settling a dispute": Dr. Jonathan Letterman and the Tortuous Path of Medical Care from Manassas to Camp Letterman," p. 101, U.S. National Park Service and Gettysburg National Military Park.

- ^ Stanton, Samuel Cecil, ed. The Military Surgeon: Journal of the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States, Vol. 33, pp. 422-429 ("Camp Letterman"). Chicago, Illinois: Association of Military Surgeons of the United States, 1913.

- ^ "History and Culture," in "Gettysburg National Military Park," U.S. National Park Service.

- ^ Tooker, John. "Antietam: Aspects of Medicine, Nursing and the Civil War," in Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 2007: Vol. 118, pp. 215-223. El Paso, Texas,: American Clinical and Climatological Association, retrieved online August 11, 2019.

- ^ Tracey, Jonathan. "Camp Letterman - The Inhumanity of War," in The Gettysburg Compiler. Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Civil War Institute, Gettysburg College, April 20, 2018.

- ^ Dr. Letterman's Gettysburg Report, in "In Their Words." Columbus, Ohio: Department of History, The Ohio State University, retrieved online August 8, 2019.

- ^ "History and Culture," in "Gettysburg National Military Park," U.S. National Park Service.

- ^ "Pennsylvania House Unanimous in Adding to GBPA Camp Letterman Preservation Drive." Gettysburg, Pennsylvania: Gettysburg Battlefield Preservation Association, June 25, 2018.

- ^ Bucklin, Sophronia E. In Hospital and Camp: A Woman’s Record of Thrilling Incidents Among the Wounded in the Late War, pp. 187-188. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: John E. Potter and Company, 1869.

- ^ Hancock, Cornelia. South After Gettysburg: Letters of Cornelia Hancock, 1863–1868, p. 14. New York, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1956.

- ^ Whitehill, Harry C. History of Waterbury Vermont, 1763–1915. Waterbury, Connecticut: The Record Print, 1915.

- ^ Atkinson, "'War is a hellish way of settling a dispute": Dr. Jonathan Letterman and the Tortuous Path of Medical Care from Manassas to Camp Letterman," p. 105, U.S. National Park Service and Gettysburg National Military Park.

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward, and Mary Hannah Graves, eds. Representative Women of New England, pp. 301–303. Boston, Massachusetts: New England Historical Publishing Company, 1904.

- ^ Alleman, Mrs. Tillie (Pierce). At Gettysburg, or What a Girl Saw and Heard of the Battle: A True Narrative. New York: W. Lake Borland, 1889.

- ^ Kessler, Jane. "Gettysburg battle witness lived in Selinsgrove." Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Daily Item, March 14, 2011.

- ^ Otto, Frank. "Phoenixville woman traveled to Gettysburg to tend to wounded." Pottsville, Pennsylvania: The Mercury, June 3, 2013.

External links

edit- Camp Letterman Hospital, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania (photo). Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Gettysburg Museum, retrieved online August 9, 2019.

- Campbell, William T. "The Pavilion-Style Hospital of the American Civil War and Florence Nightingale." Washington, D.C.: National Museum of Civil War Medicine, July 8, 2019.

- Campi Jr., James J. "Preservation of the Third Day's Battlefield: Gettysburg." Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Trust, retrieved online August 11, 2019.

- Leonard, Pat. "Nursing the Wounded at Gettysburg," in "Disunion." New York, New York: The New York Times, July 7, 2013.

- U.S. Christian Commission at Gettysburg General Hospital [Camp Letterman], August 1863 (photo). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online August 11, 2019.