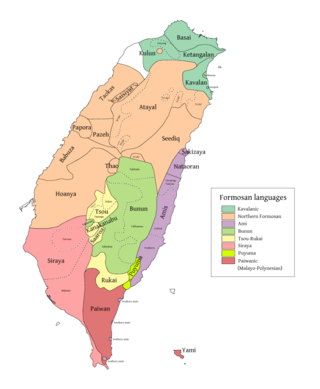

The Bunun language (Chinese: 布農語) is spoken by the Bunun people of Taiwan. It is one of the Formosan languages, a geographic group of Austronesian languages, and is subdivided in five dialects: Isbukun, Takbunuaz, Takivatan, Takibaka and Takituduh. Isbukun, the dominant dialect, is mainly spoken in the south of Taiwan. Takbunuaz and Takivatan are mainly spoken in the center of the country. Takibaka and Takituduh both are northern dialects. A sixth dialect, Takipulan, became extinct in the 1970s.

| Bunun | |

|---|---|

| Bunun | |

| Native to | Taiwan |

| Ethnicity | Bunun people |

Native speakers | 38,000 (2002)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin script | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | bnn |

| Glottolog | bunu1267 |

Distribution of Bunun language (medium green, center) | |

Bunun is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The Saaroa and Kanakanavu, two smaller minority groups who share their territory with an Isbukun Bunun group, have also adopted Bunun as their vernacular.

Name

editThe name Bunun literally means "human" or "man".

Dialects

editBunun is currently subdivided into five dialects: Isbukun, Takbunuaz, Takivatan, Takibaka and Takituduh. Li (1988) splits these dialects into three main branches — Northern, Central, and Isbukun (also classified as Southern Bunun).[2] Takipulan, a sixth dialect, became extinct in the 1970s. Isbukun, the prestige dialect, is also the most divergent dialect. The most conservative dialects are in the Northern branch.

- Proto-Bunun

- Isbukun

- North-Central

- Northern

- Takituduh

- Takibakha

- Central

- Takbanuaz

- Takivatan

- Northern

Bunun was originally spoken in and around Sinyi Township (Xinyi) in Nantou County.[3] From the 17th century onwards, the Bunun people expanded towards the south and east, absorbing other ethnic groups such as the Saaroa, Kanakanavu, and Thao. Bunun is spoken in an area stretching from Ren-ai Township in Nantou in the north to Yan-ping Township in Taitung in the south. Isbukun is distributed throughout Nantou, Taitung, and Kaohsiung. Takbanuaz is spoken in Nantou and southern Hualien County. Takivatan is spoken in Nantou and central Hualien. Both Takituduh and Takibakha are spoken in Nantou.

Proto-Bunun

editShibata (2020) has a reconstruction of Proto-Bunun.[4]

Phonology

editConsonants

edit| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ ⟨ng⟩ | ||||

| Plosive | plain | p | t | k | q | ʔ ⟨'⟩ | |

| implosive | ɓ ⟨b⟩ | ɗ ⟨d⟩ | |||||

| Fricative | v | ð ⟨z⟩ | s | χ | h | ||

| Approximant | l | ||||||

Orthographic notes:

- /dʒ/ as ⟨j⟩.

Notes:

- The glides /j w/ exist, but are derived from the underlying vowels /i u/ to meet the requirements that syllables must have onset consonants. They are therefore not part of the consonant inventory.

- The dental fricative /ð/ is actually interdental (/ð̟/).

- In the Isbukun dialect, /χ/ often occurs in final or post-consonantal position and /h/ in initial and intervocalic position, whereas other dialects have /q/ in both of these positions.

- While Isbukun drops the intervocalic glottal stops (/ʔ/) found in other dialects, /ʔ/ also occurs where /h/ occurs in other dialects. (For example, the Isbukun word [mapais] bitter is [mapaʔis] in other dialects; the Isbukun word [luʔum] 'cloud' is [luhum] in other dialects.)

- The alveolar affricate /dʒ/ occurs in the Taitung variety of Isbukun, usually represented in other dialects as /t/.[5]

Vowels

edit| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | i | u | |

| Mid | e | ||

| Low | a |

Notes:

- /e/ does not occur in Isbukun.

Grammar

editOverview

editBunun is a verb-initial language and has an Austronesian alignment system or focus system. This means that Bunun clauses do not have a nominative–accusative or absolutive–ergative alignment, but that arguments of a clause are ordered according to which participant in the event described by the verb is 'in focus'. In Bunun, three distinct roles can be in focus:

- the agent: the person or thing that is doing the action or achieving/maintaining a state;

- the undergoer: the person or thing that is somehow participating in the action without being an agent; there are three kinds of undergoers:

- patients: persons or things to whom an action is done or an event happens

- instruments: things (sometimes persons) which are used to perform an action

- beneficiaries (also called recipients): the persons (sometimes things) for whom an action is done or for whom an event happens

- the locative participant: the location where an action takes place; in languages with a Philippine-style voice system, spatial location is often at the same level in a clause as agents and patients, rather than being an adverbial clause, like in English.[6]

Which argument is in focus is indicated on the verb by a combination of prefixes and suffixes.[7]

- a verb in agent focus is often unmarked, but can get the prefix ma- or – more rarely – pa- or ka-

- a verb in undergoer focus gets a suffix -un

- a verb locative focus gets a suffix -an

Many other languages with a focus system have different marking for patients, instruments and beneficiaries,[citation needed] but this is not the case in Bunun. The focussed argument in a Bunun clause will normally always occur immediately after the verb (e.g. in an actor-focus clause, the agent will appear before any other participant) and is in the Isbukun dialect marked with a post-nominal marker a.[7]

Bunun has a very large class of auxiliary verbs. Concepts that are expressed by auxiliaries include:

- negation (ni 'be not' and uka 'have not')

- modality and volition (e.g. maqtu 'can, be allowed')

- relative time (e.g. ngausang 'first, beforehand', qanaqtung 'be finished')

- comparison (maszang 'the same, similarly')

- question words (e.g. via 'why?')

- sometimes numerals (e.g. tatini '(be) alone, (be) only one')

In fact, Bunun auxiliaries express all sorts of concepts that in English would be expressed by adverbial phrases, with the exception of time and place, which are normally expressed [clarification needed] with adverbial phrases.

Word classes

editTakivatan Bunun has the following word classes (De Busser 2009:189). (Note: Words in open classes can be compounded, whereas those in closed classes cannot.)

- Open classes

- Nouns

- Verbs

- Adjectives

- Closed classes

- Demonstratives

- Anaphoric pronouns

- Personal pronouns

- Numerals

- Place words

- Time words

- Manner words

- Question words

- Auxiliaries

Affixes

editBunun is morphologically agglutinative language and has a very elaborate set of derivational affixes (more than 200, which are mostly prefixes), most of which derive verbs from other word classes.[8] Some of these prefixes are special in that they do not only occur in the verb they derive, but are also foreshadowed on a preceding auxiliary. These are called lexical prefixes[9] or anticipatory prefixes[10] and only occur in Bunun and a small number of other Formosan languages.

Below are some Takivatan Bunun verbal prefixes from De Busser (2009).

| Type of prefix | Neutral | Causative | Accusative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Movement from | mu- | pu- | ku- |

| Dynamic event | ma- | pa- | ka- |

| Stative event | ma- / mi- | pi- | ka- / ki- |

| Inchoative event | min- | pin- | kin- |

In short:

- Movement from: Cu-

- Dynamic event: Ca-

- Stative event: Ci-

- Inchoative event: Cin-

- Neutral: mV-

- Causative: pV-

- Accusative: kV-

A more complete list of Bunun affixes from De Busser (2009) is given below.

- Focus

- agent focus (AF): -Ø

- undergoer focus (UF): -un (also used as a nominalizer)

- locative focus (LF): -an (also used as a nominalizer)

- Tense-aspect-mood (TAM) affixes

- na- irrealis (futurity, consequence, volition, imperatives). This is also the least bound TAM prefix.

- -aŋ progressive (progressive aspect, simultaneity, expressing wishes/optative usage)

- -in perfective (completion, resultative meaning, change of state, anteriority)

- -in- past/resultative (past, past/present contrast)

- -i- past infix which occurs only occasionally

- Participant cross-reference

- -Ø agent

- -un patient

- -an locative

- is- instrumental

- ki- beneficiary

- Locative prefixes

- Stationary ‘at, in’: i-

- Itinerary ‘arrive at’: atan-, pan-, pana-

- Allative ‘to’: mu-, mun-

- Terminative ‘until’: sau-

- Directional ‘toward, in the direction of’: tan-, tana-

- Viative ‘along, following’: malan-

- Perlative ‘through, into’: tauna-, tuna-, tun-

- Ablative ‘from’: maisna-, maina-, maisi-, taka-

- Event-type prefixes

- ma- Marks dynamic events

- ma- Marks stative events

- mi- Marks stative negative events

- a- Unproductive stative prefix

- paŋka- Marks material properties (stative)

- min- Marks result states (transformational)

- pain- Participatory; marks group actions

- Causative

- pa- causative of dynamic verb

- pi- causative of stative verb

- pu- cause to go towards

- Classification of events

- mis- burning events

- tin- shock events

- pala- splitting events

- pasi- separating events

- kat- grasping events

- Patient-incorporating prefixes

- bit- 'lightning'

- kun- 'wear'

- malas- 'speak'

- maqu- 'use'

- muda- 'walk'

- pas- 'spit'

- qu- 'drink'

- sa- 'see'

- tal- 'wash'

- tapu- 'have trait'

- tastu- 'belong'

- taus-/tus- 'give birth'

- tin- 'harvest'

- tum- 'drive'

- Verbalizers

- pu- verbalizer: 'to hunt for'

- maqu- verbalizer: 'to use'

- malas- verbalizer: 'to speak'

Pronouns

editTakivatan Bunun personal pronoun roots are (De Busser 2009:453):

- 1s: -ak-

- 2s: -su-

- 3s: -is-

- 1p (incl.): -at-

- 1p (excl.): -ðam-

- 2p: -(a)mu-

- 3p: -in-

The tables of Takivatan Bunun personal pronouns below are sourced from De Busser (2009:441).

| Type of Pronoun |

Root | Foc. Agent (bound) |

Non-Foc. Agent (bound) |

Neutral | Foc. Agent | Locative | Possessive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1s. | -ak- | -(ʔ)ak | -(ʔ)uk | ðaku, nak | sak, saikin | ðakuʔan | inak, ainak, nak |

| 2s. | -su- | -(ʔ)as | – | suʔu, su | – | suʔuʔan | isu, su |

| 1p. (incl.) | -at- | – | – | mita | ʔata, inʔata | mitaʔan | imita |

| 1p. (excl.) | -ðam- | -(ʔ)am | – | ðami, nam | ðamu, sam | ðamiʔan | inam, nam |

| 2p. | -(a)mu- | -(ʔ)am | – | muʔu, mu | amu | muʔuʔan | imu, mu |

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| [Root] | -is- | -in- |

| Proximal | isti | inti |

| Medial | istun | intun |

| Distal | ista | inta |

Iskubun Bunun personal pronouns are somewhat different (De Busser 2009:454).

| Type of Pronoun |

Agent | Undergoer | Possessive |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1s. | saikin, -ik | ðaku, -ku | inak, nak |

| 2s. | kasu, -as | su | isu, su |

| 3s. | saia | saiʤa | isaiʤa, saiʤa |

| 1p. (incl.) | kata, -ta | mita | imita |

| 1p. (excl.) | kaimin, -im | ðami | inam |

| 2p. | kamu, -am | mu | imu |

| 3p. | naia | inaiʤa | naiʤa |

Demonstratives

editTakivatan Bunun has the following demonstrative roots and affixes (De Busser 2009:454):

- Demonstrative suffixes

- Proximal: -i

- Medial: -un

- Distal: -a

- Demonstrative roots

- aip-: singular

- aiŋk-: vague plural

- aint-: paucal

- ait-: inclusive generic

- Demonstrative prefixes

- Ø-: visible

- n-: not visible

- Place words

- ʔiti here

- ʔitun there (medial)

- ʔita there (distal)

Function words

edit- sia anaphoric marker, "aforementioned"; also used as a hesitation marker

- tu attributive marker

- duma "others"

- itu honorific marker

Takivatan Bunun also has definitive markers.

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Proximal | -ti | -ki |

| Medial | -tun | -kun |

| Distal | -ta | -ka |

Notes

edit- ^ Bunun at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ Li, Paul Jen-kuei. 1988. A Comparative Study of Bunun Dialects. In Li, Paul Jen-kuei, 2004, Selected Papers on Formosan Languages. Taipei, Taiwan: Institute of Linguistics, Academia Sinica.

- ^ De Busser (2009), p. 63

- ^ Shibata, Kye (2020). A Reconstruction of Proto-Bunun Phonology and Lexicon (M.A. dissertation). Hsinchu: National Tsing Hua University.

- ^ De Busser, Rik (14 May 2011). Introduction to the Bunun language (PDF). Languages of Taiwan, 2011. pp. 7–8.

- ^ see Schachter & Otanes (1972) for a discussion of location in Tagalog

- ^ a b Zeitoun (2000)

- ^ Lin et al. (2001)

- ^ Nojima (1996)

- ^ Adelaar (2004)

References

edit- Adelaar, K. Alexander (2004). "The Coming and Going of 'Lexical Prefixes' in Siraya" (PDF). Language and Linguistics / Yǔyán jì yǔyánxué. 5 (2): 333–361. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-05-10.

- De Busser, Rik (2009). Towards a Grammar of Takivatan: Selected Topics (Ph. D. thesis). La Trobe University. doi:10.17613/M68D2H – via hcommons.org.

- Jeng, Heng-hsiung (1977). Topic and Focus in Bunun. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

- Nojima, Motoyasu (1996). "Lexical Prefixes of Bunun Verbs". Gengo Kenkyu: Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan. 110: 1–27. doi:10.11435/gengo1939.1996.110_1.

- Li, Paul Jen-kuei (1988). "A Comparative Study of Bunun Dialects" (PDF). Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica. 59 (2): 479–508. doi:10.6355/BIHPAS.198806.0479. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-18. Retrieved 2021-07-27.

- Schachter, Paul; Otanes, Fe T. (1972). Tagalog Reference Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Zeitoun, Elizabeth 齊莉莎 (2000). Bùnóngyǔ cānkǎo yǔfǎ 布農語參考語法 [Bunun Reference Grammar] (in Chinese). Taibei Shi: Yuan liu. ISBN 957-32-3891-8.

- Lin, Tai 林太; Zeng, Si-qi 曾思奇; Li, Wen-su 李文甦; Bukun Ismahasan Islituan 卜袞‧伊斯瑪哈單‧伊斯立瑞 (2001). Isbukun: Bùnóngyǔ gòucífǎ yánjiū Isbukun: 布農語構詞法研究 [Isbukun: A Study on Word Formation in Bunun] (in Chinese). Taibei: Du ce wenhua.

- Anu Ispalidav (2014). Bùnóngzú yǔ dúběn: Rènshí jùn qún Bùnóngzú yǔ 布農族語讀本: 認識郡群布農族語 [Bunun Reader: Understanding the Bunun Language] (in Chinese). Taibei Shi: Shitu chuban she.

- Huang, Hui-chuan 黃慧娟; Shih, Chao-kai 施朝凱 (2018). Bùnóngyǔ yǔfǎ gàilùn 布農語語法概論 [Introduction to Bunun Grammar] (in Chinese). Xinbei Shi: Yuanzhu minzu weiyuanhui. ISBN 978-986-05-5687-2. Archived from the original on 2022-02-17. Retrieved 2021-07-27 – via alilin.apc.gov.tw.

External links

edit- Kaipuleohone's Robert Blust collection includes elicited materials on Bunun.

- Yuánzhùmínzú yǔyán xiànshàng cídiǎn 原住民族語言線上詞典 (in Chinese) – Bunun search page at the "Aboriginal language online dictionary" website of the Indigenous Languages Research and Development Foundation

- Bunun teaching and leaning materials published by the Council of Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan Archived 2022-02-17 at the Wayback Machine (in Chinese)

- Bunun translation of President Tsai Ing-wen's 2016 apology to indigenous people – published on the website of the presidential office