The brush-tailed rock-wallaby or small-eared rock-wallaby (Petrogale penicillata) is a kind of wallaby, one of several rock-wallabies in the genus Petrogale. It inhabits rock piles and cliff lines along the Great Dividing Range from about 100 km north-west of Brisbane to northern Victoria, in vegetation ranging from rainforest to dry sclerophyll forests. Populations have declined seriously in the south and west of its range, but it remains locally common in northern New South Wales and southern Queensland.[4] However, due to a large bushfire event in South-East Australia around 70% of all the wallaby's habitat has been lost as of January 2020.

| Brush-tailed rock-wallaby[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| In the Watagan Mountains on the NSW | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Petrogale |

| Species: | P. penicillata

|

| Binomial name | |

| Petrogale penicillata (J. E. Gray, 1827)[3]

| |

| |

| Brush-tailed rock-wallaby range | |

In 2018, the southern brush-tailed rock wallaby was declared as the official mammal emblem of the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), although it has not been seen in the wild in the ACT since 1959.[5]

Taxonomy

editPetrogale penicillata was first described by John Edward Gray in 1827.[3] The taxon has been named for a species complex, the Petrogale penicillata-lateralis group, the systematics of which continued to be resolved.

Description

editA species of Petrogale, rock wallabies have a dense and shaggy pelage that is rufous or grey brown. The tail is 500 to 700 millimetres long, exceeding the 510 to 580 mm combined length of the head and body. The colour of the tail is brown or black, the fur becoming bushy towards its shaggy, brush-like end. The weight range is from 5 to 8 kilograms. The upper parts of this wallaby's pelage is either entirely rufous-brown, or a grey brown over the back and shoulders with brown fur at the thigh and rump. The paler under parts may feature a white blazon on the chest. Very dark fur covers the lower parts of the limbs, paws and feet, and on the sides beneath the fore limbs of the animal; a whitish stripe may appear along the side of the body.[6]

The coloration of the species in the northern parts of population is paler and fur is shorter in length. The black-footed and flanked species Petrogale lateralis, which occurs in central Australia, is distinguished by its larger size and the shorter and darker fur of the tail and hind parts. Herbert's rock-wallaby (P. herberti) overlaps in the northern range of this species, their coloration is greyer than the warm brown of this species and lighter at the darker features of the limbs; the tail of that species also lacks the blackish features and bushy end.[6] The pads of the feet are well developed and their coarse texture allows good traction on rock surfaces.[7]

Behaviour

editThe species is able to negotiate difficult rocky terrain with great agility, their compact yet powerful build is assisted by counter-balancing the long tail and feet suited to holding the animal at precarious edges and on inclined surfaces. The species favours north facing refuges, and while largely nocturnal in venturing out from shelter they will bask in winter sun for short periods. Procreation is founded on breeding females utilising a single male for insemination, with births that occur throughout the year. Groups in cooler latitudes or higher altitudes may tend to reproduce in a period between February and May. The females of the colony cohere as maternal groups, with male progeny moving to other groups within the colony or migrating to another location. Individual foraging territories for the species are around 15 hectares, perhaps more for males.[7]

Distribution and habitat

editFound along the Great Dividing Range in fragmented populations that remain after its historical contraction in range from the east and south. The southern edge of the range is the Grampians, and no further west than the Warrumbungles range in New South Wales. The northernmost groups have remained less affected by ecological changes, these are found in southeast Queensland.

Petrogale penicillata shelters during the day in rocky habitat, within vegetation or cavities of preferably complex terrain that allows them to find cooler temperatures and to elude or remain inaccessible to predators. Their great agility while hopping and climbing provides opportunities at ledges, cliff-faces, overhangs, caves and crevices.[7]

Introduced populations

editAs part of the acclimatisation movement of the late 1800s, governor Grey introduced this and four other species of wallabies (including the rare parma wallaby) to islands in Hauraki Gulf, near Auckland, New Zealand, where they became well-established. In modern times, these populations have come to be viewed as exotic pests, with severe impacts on the indigenous flora and fauna. As a result, eradication is being undertaken, after initial protection for review of their Australian populations and the return of some wallabies to Australia. Between 1967 and 1975, 210 rock-wallabies were captured on Kawau Island and returned to Australia, along with thousands of other wallabies.[8] Rock-wallabies were removed from Rangitoto and Motutapu Islands during the 1990s, and eradication is now underway on Kawau. Another thirty-three rock-wallabies were captured on Kawau during the 2000s, and returned to Australia, before eradication began.[9][10]

In 2003 some Kawau brush-tails were relocated to the Waterfall Springs Conservation Park north of Sydney, New South Wales, for captive breeding purposes.

Due to an escape of a pair in 1916, a small breeding population of the brush-tailed rock-wallabies also exists in the Kalihi Valley on the island of Oahu in Hawaii.

Attempts at reintroduction into the Grampians National Park during 2008-12 were not successful, largely due to fox predation.[11] Nevertheless, March 2017 saw the emergence of a fourth offspring, bringing the total number of rock–wallabies present within the Grampians National Park to eight.[12]

Conservation

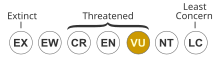

editThe Brush-tailed rock wallaby was once common throughout South-East Australia, but due to clearing of native habitat, exotic plant introduction, predation by introduced species and changing fire patterns as a result of climate change they have been wiped out from much of their Southern and Western ranges.

In late 2019 fierce bushfires swept through New South Wales and Victoria, burning protected areas inhabited by the wallaby. It is estimated that 70% of all brush-tailed rock-wallaby habitat was destroyed. In the aftermath of the fires in Victoria, where the wallaby was thought to have been hunted to extinction by the early 20th century by settlers who prized its fur and skin, until some who had survived were discovered in the Grampians in 1970,[13] a colony of 13 has been detected in the Grampians National Park while a further 50 are known to exist in the Snowy River National Park.[14]

References

edit- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 68. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Woinarski, J.; Burbidge, A.A. (2016). "Petrogale penicillata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T16746A21955754. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T16746A21955754.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gray, J.E. (1827). "Synopsis of the species of mammalia". In Griffith, E.; Pidgeon, E.; Smith, C.H. (eds.). The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organisation by the Baron Cuvier, member of the Institute of France etc. with additional descriptions of all the species hitherto named, and of many not before noticed. Vol. 5. pp. 185–206 [204].

- ^ A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia, Menkhorst, P and Knight, F, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, 2001 ISBN 0-19-550870-X

- ^ "ACT receives new mammal emblem". 29 November 2018.

- ^ a b Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 136. ISBN 9780195573954.

- ^ a b c "Brush-tailed Rock-wallaby - profile". www.environment.nsw.gov.au. NSW Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ^ Shaw, W.B.; Pierce, R.J. 2002: Management of North Island weka and wallabies on Kawau Island. Department of Conservation Science Internal Series 54. Department of Conservation, Wellington. ISBN 0-478-22272-6.

- ^ "Rock wallabies". Catalyst. ABC. 4 March 2004. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ "Saving the Brush-tailed Rock Wallaby". Waterfall Springs Wildlife Sanctuary. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Taggart, D.A.; Schultz, D.J.; Corrigan, T.C.; Schultz, T.J.; Stevens, M.; Panther, D.; White, C.R. (2016). "Reintroduction methods and a review of mortality in the brush-tailed rock-wallaby, Grampians National Park, Australia". Australian Journal of Zoology. 63 (6): 383–397. doi:10.1071/ZO15029. S2CID 87455828.

- ^ Hayter, Rachel (12 March 2017). "Joey marks end of 'tough times' for resurgent rock-wallabies in western Victoria". ABC News. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Benjamin Wilkie, Gariwerd: An Ecological History of the Grampians, Csiro Publishing 2020 ISBN 978-1-486-30769-2 pp.73-74.

- ^ Miki Perkins, 'Incredibly exciting': These marsupials are endangered. Now, there's new life and hope, The Age 20 October 2020.

External links

edit- Brush-tailed rock-wallaby recovery in NSW (Foundation for National Parks & Wildlife)

- Brush-tailed rock-wallaby population in Green Gully - a conservation case study

- Brush-tailed rock-wallaby habitat modelling

- BBC video of brush-tailed rock-wallabies in action Archived 2011-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- The Aussie Brush-Tailed Rock-Wallaby Ark Conservation Project Archived 2021-05-13 at the Wayback Machine