The British Columbia wolf (Canis lupus columbianus) is a subspecies of gray wolf which lives in a narrow region that includes those parts of the mainland coast and near-shore islands that are covered with temperate rainforest, which extends from Vancouver Island, British Columbia, to the Alexander Archipelago in south-east Alaska.[3] This area is bounded by the Coast Mountains.[4]

| British Columbia wolf | |

|---|---|

| |

| Melanistic C. l. columbianus, Lower Post, British Columbia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. l. columbianus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus columbianus Goldman, 1941[2]

| |

| |

| Historical and present range of gray wolf subspecies in North America | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Canis crassodon columbianus | |

Taxonomy

editThe wolf was first classed as a distinct subspecies in 1941 by Edward Goldman, who described his specimen as being large with a skull closely resembling that of C. l. pambasileus, and whose fur is generally of a cinnamon-buff colour.[2] This wolf is recognized as a subspecies of Canis lupus in the taxonomic authority Mammal Species of the World (2005).[5]

Studies using mitochondrial DNA have indicated that the wolves of coastal south-east Alaska are genetically distinct from inland gray wolves, reflecting a pattern also observed in other taxa.[4][6][7] They show a phylogenetic relationship with extirpated wolves from the south (Oklahoma), indicating that these wolves are the last remains of a once widespread group that has been largely extirpated during the last century, and that the wolves of northern North America had originally expanded from southern refuges below the Wisconsin glaciation after the ice had melted at the end of the Last Glacial Maximum. These findings call into question the taxonomic classification of C. l. nulibus proposed by Nowak.[4] Another study found that the wolves of coastal British Columbia were genetically and ecologically distinct from the inland wolves, including other wolves from inland British Columbia.[3] A study of the three coastal wolves indicated a close phylogenetic relationship across regions that are geographically and ecologically contiguous, and the study proposed that Canis lupus ligoni (Alexander Archipelago wolf), Canis lupus columbianus (British Columbia wolf), and Canis lupus crassodon (Vancouver Island wolf) should be recognized as a single subspecies of Canis lupus.[7]

In 2016, two studies compared the DNA sequences of 42,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms in North American gray wolves and found the coastal wolves to be genetically and phenotypically distinct from other wolves.[8] They share the same habitat and prey species, and form one of the study's six identified ecotypes – a genetically and ecologically distinct population separated from other populations by their different type of habitat.[8][9] The local adaptation of a wolf ecotype most likely reflects the wolf's preference to remain in the type of habitat that it was born into.[8] Wolves that prey on fish and small deer in wet, coastal environments tend to be smaller than other wolves.[8]

Description

editThe British Columbia wolf is one of the largest subspecies of North American wolves. They weigh around 80 (36 kg) to 150 pounds (68 kg) and are roughly 5ft (152 cm) to 5ft 10 (178 cm) long. These wolves have long coats which were usually black, often mixed with grey, or brown. [10]

References

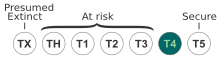

edit- ^ "Canis lupus". explorer.natureserve.org.

British Columbia: S4S5

- ^ a b Goldman, E. A. (1941). "Three new Wolves from North America". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 54: 109–113.

- ^ a b Muñoz-Fuentes, Violeta; Darimont, Chris T.; Wayne, Robert K.; Paquet, Paul C.; Leonard, Jennifer A. (2009). "Ecological factors drive differentiation in wolves from British Columbia". Journal of Biogeography. 36 (8): 1516–1531. Bibcode:2009JBiog..36.1516M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2008.02067.x. hdl:10261/61670. S2CID 38788935.

- ^ a b c Weckworth, Byron V.; Talbot, Sandra L.; Cook, Joseph A. (2010). "Phylogeography of wolves (Canis lupus) in the Pacific Northwest". Journal of Mammalogy. 91 (2): 363–375. Bibcode:2010JMamm..91..363W. doi:10.1644/09-MAMM-A-036.1.

- ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 575–577. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA576

- ^ Weckworth, Byron V.; Talbot, Sandra; Sage, George K.; Person, David K.; Cook, Joseph (2005). "A Signal for Independent Coastal and Continental histories among North American wolves". Molecular Ecology. 14 (4): 917–31. Bibcode:2005MolEc..14..917W. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02461.x. PMID 15773925. S2CID 12896064.

- ^ a b Weckworth, Byron V.; Dawson, Natalie G.; Talbot, Sandra L.; Flamme, Melanie J.; Cook, Joseph A. (2011). "Going Coastal: Shared Evolutionary History between Coastal British Columbia and Southeast Alaska Wolves (Canis lupus)". PLOS ONE. 6 (5): e19582. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...619582W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0019582. PMC 3087762. PMID 21573241.

- ^ a b c d Schweizer, Rena M.; Vonholdt, Bridgett M.; Harrigan, Ryan; Knowles, James C.; Musiani, Marco; Coltman, David; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Genetic subdivision and candidate genes under selection in North American grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (1): 380–402. Bibcode:2016MolEc..25..380S. doi:10.1111/mec.13364. PMID 26333947. S2CID 7808556.

- ^ Schweizer, Rena M.; Robinson, Jacqueline; Harrigan, Ryan; Silva, Pedro; Galverni, Marco; Musiani, Marco; Green, Richard E.; Novembre, John; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Targeted capture and resequencing of 1040 genes reveal environmentally driven functional variation in grey wolves". Molecular Ecology. 25 (1): 357–79. Bibcode:2016MolEc..25..357S. doi:10.1111/mec.13467. PMID 26562361. S2CID 17798894.

- ^ "British Columbia Wolf". brainsonswildworld.com.