Britannia Village (est. 1818)[7][8] has a rich history and architecture, having been founded some eight years before Bytown (est. 1826),[9] the former name of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. The history of the village is interwoven with the creation of the adjacent Britannia Amusement Park, today simply known as Britannia Park. The character of villagers is significantly influenced by its natural surroundings.

Britannia Village, Ottawa | |

|---|---|

Neighbourhood | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°22′07.7″N 75°47′59.2″W / 45.368806°N 75.799778°W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Ontario |

| City | Ottawa |

| Government | |

| • MPs | Anita Vandenbeld |

| • MPPs | Jeremy Roberts |

| • Councillors | Theresa Kavanagh |

| • Governing body | Britannia Village Community Association |

| • President | Jonathan Morris |

| Elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 610 |

| Statistics Canada 2021 Census | |

| Website | bvcaottawa |

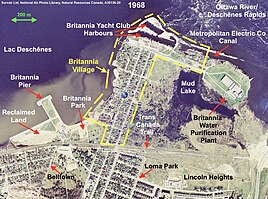

Geographically, the village is located on a broad peninsula and is largely defined by natural boundaries. According to the Ottawa Neighborhood Study,[10] the village is bordered by the Ottawa River to the North, Lac Deschênes and Britannia Park to the west, the Trans Canada Trail to the south, and Mud Lake[11] (Britannia Conservation Area, 79 hectares[12]) to the east. Lac Deschênes is home to 4 sailing clubs including the Britannia Yacht Club which is located in the village. The village also borders on Britannia Beach, one of four beaches in Ottawa.[13] Britannia Road is the only road into and out of the village and the only access to the Britannia Water Purification Plant.[14]

The village has a total population of 610 people in 270 private households;[15] it is a sub-neighborhood of the Britannia area of Bay Ward, in the west end of Ottawa about 13 km from the Canadian Parliament Buildings. The village has an active association (Britannia Village Community Association or BVCA)[16] and a community Facebook page (Friends of Britannia Village).[17]

History

editThe archaeological record from the early 1900s provides ample evidence of Indigenous peoples on the beaches of Lac Deschênes, and hence in and around the village; the evidence is largely in the form of indigenous beach workshops where the Algonquin Anishinaabe would chip out flint arrowheads or laboriously grind an edge into a stone tomahawk.[18][19]

Mill town (1826–1887)

editIn 1826, Captain John Le Breton,[20] a seriously injured soldier in the War of 1812, first established a flour mill and then a successful lumber mill in the village, then part of the Nepean Township.[21] At the time, as part of the Ottawa River timber trade, logs were floated[22] down the river in timber rafts (bundled logs) to get to the burgeoning construction market in Bytown (Ottawa), some 14 km away. However, the Deschênes Rapids, with its vertical drop of about 9 ft,[23] presented a formidable challenge. The timber rafts had to be disassembled, guided through the rapids one log at-a-time by 2 or 3 raftsmen, and subsequently reassembled.[24][25] By creating a mill at the head of the Deschênes Rapids, Le Breton was able to convince logging companies to cut their logs at his sawmill to avoid the cost of both reassembling the timber rafts and floating them to Bytown. LeBreton transported the cut lumber overland by horse and cart to Bytown along Richmond Rd that had been created a few years earlier.[7] Mill workers included labourers and carpenters, and most lived in the village.

The mill changed owners (Nelson G. Robinson, 1846; John McAmmond Jr., 1873),[26] eventually producing up to 100,000 boards per year (1860),[27] and also including a carding mill, carpenter shop and a forge.[28] In the process, a second sawmill was established in the village along the bay near the foot of Rowatt St.[29] The last owner of the mills (John C. Jamieson[30]) could not make the business profitable because of a stock market crash and competition from larger mills.[31] In 1887, rather than converting the mills into pulp and paper factories, which some of his competitors were doing, Jamieson chose to convert them into summer rental residences with ample storage space underneath for boats.[32] By 1875, a post office (48 Britannia Rd) had been established in the village on the basis of 25 residences.[33]

Summer-cottage resort (1887–1960)

editCottage-building in the village flourished at the beginning of this era because of the creation of a major amusement park adjacent to the village and the establishment of a boat club in 1887.[34] The main tourist attraction in the amusement park was a long, thin, wooden pier which was built on the rubble from a canal intended for generating power.

Engineering feats

editFollowing the invention of dynamite in 1867, the Metropolitan Electric Co. excavated a canal (14 ft deep × 150 ft wide × 2,000 ft long)[35] on the north shore of the village to generate electricity (see photo gallery below). The Hull Electric Company had already successfully used the Deschênes Rapids to generate electricity on the other side of the Ottawa River.[36] Between 1898 and 1901, Metropolitan Electric employed up to 500 workers and spent nearly half a million dollars[37] (about $17M in 2022 dollars). The company ran out of money and the project was abandoned before the powerhouse could be installed.[38] Most of the rubble from the excavation was piled alongside the canal; on the north side, this resulted in the formation of a thin island that is easily visible when standing on the shore of the river at the Britannia Water Purification Plant. Rubble piled on the south side resulted in a large breakwater that now has a hiking trail on top of it. At the time, the canal construction project was very newsworthy and a timeline compilation of 46 archived newspaper articles is available,[39] as are online photographs.[40]

-

Metropolitan Electric Co. excavated a canal intended to generate power (1898–1901). As a byproduct, large boulders were hauled about 1 km by horse/cart to provide the foundation of the Britannia Pier (1899).[d]

-

Although the company ran out of money before the powerhouse could be installed, the Britannia Yacht Club used the canal to create two harbours in two phases (1935).

-

Phase 1 (1950–1951): Crimson Cove and Mauve Cove are incorporated into the property of the Britannia Yacht Club by using fill/concrete to dam the canal and create the main harbour entrance (1960).

-

Phase 2 (1963–1969): Britannia Island is incorporated into the property of the Britannia Yacht Club to create the inner harbour, one of the best-sheltered yacht harbours in North America (2022).[41]

Even though the hydroelectric project failed, its byproducts served two useful purposes. First, large boulders from the excavated canal were used as the foundation for the wooden Britannia Pier.[42] In February, 1900, men cut a huge hole in the ice to the bottom of Lac Deschênes in the shape/dimensions of the pier (i.e. 30 ft by 1,050 ft, later extended to 1,450 ft[42]); large boulders were then carted by 25 teams of horses from the south shore of the Metropolitan Electric canal and dumped/layered into the hole. The top of the layered stones was covered with concrete and the wooden pier was built on top.[43] Secondly, some 50 years later, the Britannia Yacht Club (Thomas Fuller, Reginald Bruce, and many volunteers recruited by the Ladies Auxiliary) used the excavated canal to create two protected harbours for mooring some 250 boats. This was accomplished in two phases from 1950 to 1969 by damming the canal, annexing two small islands plus Britannia Island[44][e] just north of the canal, joining them all to their property, digging out the harbours, and building about one mile of harbour walls, all with an enormous amount of fill/concrete.[47]

Britannia Amusement Park

editIn 1900, the Ottawa Electric Railway (OER) company opened an 18-acre amusement park which was expanded to 53 acres in 1904;[48] the firm purchased the land from Britannia Village landowners.[49] An estimated 12,000 to 15,000 visitors attended the opening of the park.[42] Like other transportation companies of the era, OER electric trolleys were busy during the workweek but under utilized during the weekend. In an era without cars, the OER built the park as a fresh-air, weekend escape from polluted Bytown, thereby increasing their trolley use and income.[42] The park was also serviced by a Canadian Pacific Railway line.

The park became one of Canada's top tourist attractions at the time,[42] and facilitated a rapid residential housing/cottage boom in the village.[50][51] In 1890, 1900 and 1910, the combined number of cottages and permanent residences in the village was 38, 83 and 166, respectively.[52] During this era, the village also became quite fashionable when several prominent Ottawa figures began to reside there.[7] The park had a reputation as the People's Playground.[53]

(based on a 1910 map from the Ottawa Electric Railway company)[54]

-

The wooden, 442m-long Britannia pier. During the 1960s, the pier was widened from about 9m to 74m (consult GeoOttawa aerial photos timeline[6]). The village is to the left of Lakeside Gardens (1920).

-

Both the train and the trolley brought visitors to the park. The Britannia trolley station was the last stop before the trolley entered the roundabout to return to Ottawa (1927).

-

The footbridge allowed trolley passengers to safely cross the train tracks into the park; it was a major attraction for youngsters who ascended to view the approaching smoke-billowing trains (1952).

-

Trolley waiting at the Britannia trolley station alongside a locomotive. The train track evolved into the Trans Canada Trail. The park also had a mini train for children (1958).

Over time, the park facilities included the trolley station, a tall footbridge over the CPR railway tracks, 65 dressing rooms for swimmers in 2 pavilions, a merry-go-round, a miniature train, donkey rides, a 700-person auditorium (Lakeside Gardens), the wooden Britannia Pier complete with a wharf and three-story boating clubhouse, and a summer hotel at the intersection of Bradford and Rowatt.[55][50][42] Moonlight excursions on the G.B. Greene, a 255 tonne/250 passenger riverboat were in high demand.[56] Easily-accessible electric trolley service from Ottawa to Britannia Park at 7 cents a ride brought thousands of tourists per day[10] during the summer months.[57] Lakeside Gardens featured Sunday night concerts, drama night, films and dancing on Fridays and Saturdays supervised by the Kiwanis Club. As many as 8,000 per season attended these dances.[58] Society's fascination with trains and trolleys during this era was evidenced by three separate rail systems operating in the park, whereas today there are none.

The slow demise of the "electric park" began when the G.B. Greene riverboat and the boat clubhouse on Britannia Pier burned in 1916 and 1918, respectively.[42] The demise accelerated in the mid-1940s when widespread availability of automobiles allowed people to reach other entertainment destinations.[50] The park was annexed by the City of Ottawa in 1951,[50] and by 1955, much of its original infrastructure, including the long pier and Lakeside Gardens, had either rotted, burned or been demolished.[42] The trolley line to the park was decommissioned in 1959.[42] The train track was removed in 1967 and replaced in the early 70s by a bicycle path (i.e. the Trans Canada Trail).[59] In a bygone era lasting some 60 years, the park had been the playground of eastern Ontario.[60] Today, the park is simply known as Britannia Park, whereas the Britannia Amusement Park is listed in Closed Canadian Parks[61] as one of 9 closed amusement parks that were built or nurtured by transportation companies.[62]

Rural commuter town (1960–2000)

editDuring this era, Britannia, and by association the village, garnered a reputation of being a rural commuter town. Although the village had been established in 1818, it was only annexed by the City of Ottawa in 1950,[50] and therefore, did not receive city services until after that date. Even though the installation of sewers in Ottawa had begun in 1875,[63] Britannia was only serviced in 1960; at that time, Britannia was notorious at Ottawa City Hall for sporting most of Ottawa's remaining 185 outhouses.[64] Prior to the installation of water mains in the village, water had been provided for park facilities and for some paying village residences by two water towers, one installed privately by Gerald Jamieson (son of John Jamieson), and by wells and rain barrels.[65] In 1959, a City of Ottawa survey showed that nearly half of the dwellings in the village were deemed to be in poor or very poor condition.[66]

The long delay in the installation of sewers and water soiled the reputation of Britannia, including the village, and lowered land/house prices and taxes. This reduced living costs in the village and made it attractive to families that couldn't afford to live in Ottawa. Cheap fares on the trolley and later buses, allowed workers to readily commute from the village to Ottawa for work.

Revitalization (since 2000)

editFlood proofing

editFrom 2007 to 2018, the Britannia Village Community Association worked with the City of Ottawa and the Rideau Valley Conservation Authority to reduce the risk of flooding in the village.[67] This involved the construction of berms, gates and a pump station designed to regulatory standards for flood proofing in Eastern Ontario (i.e. 1-in-100 year flood event[68][69]). Even in the case of an extreme climate change event, flood plain maps (i.e. 1-in-350 year flood event[70]) show that many residences in the village would not get floodwaters on their property.

Gentrification

editSince about 2000, rapid gentrification has resulted in considerable renovation, demolition and construction of many elaborate residences in the village.

Heritage buildings and architectural style

editThe village exhibits a large diversity of architectural styles since residences were built in a variety of eras; it was not developed as a planned community but rather as a cottage district which grew and developed over time.[71] "Historic" Britannia Village is well represented by 31 buildings that the City of Ottawa has deemed to have heritage status,[72] a designation applied to buildings of significant cultural heritage value; by comparison, Lincoln Heights and Belltown, which border the village, have a total of three combined. These heritage houses, often in vernacular architecture, usually have brick or wood siding including board-and-battan, clapboard or shiplap, and most were constructed in the late 1800s (14) and in the first decade of the 1900s (14).[72] Many exhibit Queen Anne style architecture characterized by eclecticism, asymmetry, contrast and even excess.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the main architectural style of new housing was the flat-roofed duplex and some row housing.[73] Many village duplexes were originally built in areas that were subsequently re-zoned to R10[74][75] (detached dwelling residential area) with the intent of preserving the heritage of the neighborhood. Recently, in response to new Ontario legislation (Bill 23, More Homes Built Faster Act, 2022) [76] ), the City of Ottawa has released (May 31, 2024) a discussion document[77] regarding new zoning by-law provisions, and an address-searchable zoning map.[78]

Addresses of buildings with heritage status

editSince 1975, the Ontario Heritage Act,[79] has enabled the City of Ottawa to protect heritage sites, districts, marine heritage sites and archeological resources. Until recently, only seven heritage properties had been designated in the village. However, in 2024, prompted by Ontario’s Bill 23, seven more properties in the village were designated as heritage properties, including the Britannia Yacht Club. This action created some controversy when some owners objected claiming that their properties were dilapidated beyond repair or that the heritage designation limited their options in the future.[80] The justification (cultural and architectural) for heritage designation of these seven properties is included in a 15-min-video presentation to the City’s Built Heritage Committee.[81]

The village has two types of heritage buildings that are protected under the Ontario Heritage Act:

A) Protected by "Individual Designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act (Ontario Regulation 9/06)".[82] Alterations, additions or partial demolition of these properties require a heritage permit from the City of Ottawa.[83] In corresponding order, the following 14 buildings are protected individually by Bylaws# 20–97, 2024-311, 2024–252, 169–94, 09–94, 2024–253, 20–97, 237–95, 20–97, 196–01, 2024–254, 2024–255, 2024–256, 2024–257:[1]

- Bradford St: 66 (Rowatt House), 119, 205, 84 (Arbour House)

- Britannia Rd: 48 (1st post office), 73, 127 (William Murphy House), 154, 175 (a Murphy Brothers' Cottage), 181 (St. Stephen's Anglican Church)

- Kirby Rd: 95 (The Gables)

- Rowatt St: 2764 (Jamieson House), 2775

- Cassels St: 2777 (Britannia Yacht Club)

B) Interim Protection under Section 27 (1.2) of the Ontario Heritage Act.[72] There are no restrictions on alterations to properties listed on the Heritage Register. Owners must provide the City of Ottawa with 60 days' notice of intent to demolish or remove a building.[83]

- Britannia Rd: 63, 90, 141, 190-192, 195, 220, 229, 230, 236, 240, 238A-238B

- Bradford St: 54, 64, 155, 195

- Cassels St: 2780

- Rowatt St: 2748

Heritage attributes in modern residences

editThe BVCA, architects like John Riordan,[84] and previously the Britannia Village Advocacy[85] (1996), have tried to preserve the eclectic character of the village by encouraging the incorporation of heritage attributes into new structures and renovations, as shown below.

-

a) Board-and-Battan siding,[72] b) Square-post ornamentation,[86] c) Shingle-style, gable apex ornamentation,[87] d) Front verandah[84] (built, 2006)

The most iconic village heritage attribute featured in several village residences is probably the semi-circular, inset upper balcony[2] which is also featured on the top of the Britannia Village sign. Although this heritage attribute is relatively uncommon, it does exist elsewhere.[89] The City of Ottawa heritage plaque at 175 Britannia Road describes this architectural style as a Murphy Brothers' Cottage. Access to fresh air through the incorporation of verandas and balconies featured prominently in late 1800 and early 1900 architecture.

Character

editThe village is at the centre of a recreational hub with boating at the Britannia Yacht Club, hiking in Mud Lake,[11] cycling on the Trans Canada Trail, and volleyball, summer and winter swimming, kitesurfing, fishing and picnicking at Britannia Beach and Park. Consequently, many villagers are focused on the outdoors. In the winter, villagers are increasingly using the recently created (2019) Britannia Winter Trail[91] for cross-country skiing, walking and winter biking. Bird watching is also popular in the village because adjacent Mud Lake is in a major migratory corridor that is recognized as one of the most popular urban sites for bird watching in Canada.[11]

Annual village events include the Britannia Village Community Arts Crawl[92] celebrating local artists and musicians, a fall fundraising/social event, garage sale, Jane's Walk of the historic area and regular house potluck dinners. The Bring-on-the-Bay 3km and 1.5km open-water swim from the Nepean Sailing Club to the Britannia Yacht Club hosts some 800 swimmers annually.[93]

The annual IronMan Canada event[94] will be held in Ottawa on August 3, 2025, with the 4.2km swim loop[95] running parallel to the village in Lac Deschênes.

Notables in the community

edit- John Le Breton[20] (1779–1848). War hero; lumber baron; land developer (Lebreton Flats)

- Thomas G. Fuller (1908–1994). War hero (Pirate of the Adriatic);[96] founder of Thomas Fuller Construction

- Bruce Kirby CM (1929–2021). Sailboat designer including the Laser,[97] and an Olympian

- Sheila Copps CM (born 1952). First woman Deputy Prime Minister of Canada, 1993–1997

- Kevin Page (born 1957). First Parliamentary Budget Officer for Canada, 2008–2013

- Richard Reed Parry (born 1977). Core member of the Grammy Award-winning indie rock band Arcade Fire

Notes

edit- ^ The map was photographed in 1968 from an altitude of approximately 2,400 meters. The current village boundaries are the same as they were in 1968.

- ^ In 1900, the beach was on both sides of Britannia Pier. During the 1960s, Britannia Park was expanded through land reclamation[5] on both the east and west side of the pier; in the process, the beach on the west side was obliterated and replaced with grass. On the map, the retaining wall on the left side of the pier shows the extent of the reclamation.

- ^ The original Britannia Pier (30 ft wide) built in 1900 was widened by the City of Ottawa to approximately 260 ft in the 1950/60s. The original, T-shaped pier can be seen on the map embedded on the left side of the widened pier. During the 70s, a beach and three breakwaters were added to the end of the pier. Consult the GeoOttawa aerial photo timeline slider[6] for more detailed photos of this development.

- ^ Multiple drilling rigs were used to drill holes that were subsequently filled with an explosive and a detonator. After detonation, stone rubble was moved to either the north or south side of the canal.

- ^ Although Britannia Island is still officially named in the Ontario Geographic Names database,[45] the Britannia Yacht Club has renamed it Emerald Cove.[46]

References

edit- ^ a b c d "Ontario Heritage Act Register". Province of Ontario. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ a b c Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 11.

- ^ "Individually-designated heritage properties in Ottawa" (PDF). City of Ottawa. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ Reichert, RD; St Amour, EC (November 11, 2023). "An Alternative to the Pushpin Map in the Neighbourhood Infobox" (PDF). WikiConference North America, Toronto, Canada. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Arnott, W.M. (3 November 1960). "City's land reclamation program nets 100 acres (page 10)". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ a b "GeoOttawa Aerial Photos Timeline Slider". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- ^ a b c Wilson, E (10 May 1934). "Quiet old Village of Britannia was busy place half a century ago". The Evening Citizen. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 21: “Col. Joseph Bouchette, British Dominions of North America, Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Green, volume 1 (London, 1832).”

- ^ "The Corporation of Bytown". The Historical Society of Ottawa. 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ a b "Britannia Village". Ottawa Neighbourhood Study. University of Ottawa. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b c "Mud Lake". National Capital Commission. Government of Canada. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Conservation Areas in Ottawa". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 1 January 2024.

- ^ "Swim and sunbathe at Ottawa's sandy beaches". Ottawa Tourism and Convention Authority. Government of Ontario. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Britannia Water Purification Plant – Annual Report 2020" (PDF). City of Ottawa. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Complements of Statistics Canada (Custom Services – Central Region) who geocoded the village geography against their geographic database and then used an automated tool to provide the 2021 census data.

- ^ "Britannia Village Community Association". Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Friends of Britannia Village". Facebook. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ "Sowter, TWE (1900). "Archeology of Lake Deschênes". The Ottawa Naturalist. Vol. X111, No. 10: 225-238".

- ^ "Sowter, TWE (1901). "Prehistoric camping grounds along the Ottawa River". The Ottawa Naturalist. Vol. XV, No. 6: 141-151".

- ^ a b Roberts, D (1988). "Le Breton, John". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. University of Toronto. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 9, 21, 28.

- ^ Garceau, Raymond (1957). "Log drive". National Film Board of Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ Small, Henry Beaumont (1866). "The Canadian Handbook and Tourists' Guide". M. Longmoore, Montreal. p. 106. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 8, 9.

- ^ Mika, Nick; Mika, Helma (1982). Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa. Mika Publishing Company. p. 120. ISBN 0-919303-60-9.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 21, 38.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 13: "Public Archives of Canada, Census of the Canadas, 1860-61, Nepean Township (Reel C-1013), Enumeration District 3, pg. 11."

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 28, 33.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 12.

- ^ "John Cameron Jamieson Obituary". Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 41.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 41,42.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 40.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 43.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 61.

- ^ "Bistro 1908, Formerly the Hull Electric Company". Canadian Museum of History. Government of Canada. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 107, 108.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 61, 62.

- ^ Churcher, Colin J. (30 June 2021). "Newspaper timeline compilation of the construction of the Britannia Power Canal" (PDF). Flickr. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Photographs of the construction of the Britannia Power Canal". Flickr. Colin J. Churcher. 30 June 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Britannia Yacht Club: A History of Water, Place and People, 1887 – 2012. Ottawa: Britannia Yacht Club. 2013. p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Powell, J. "Britannia-on-the-Bay, May 24, 1990". The Historical Society of Ottawa. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ "Going ahead fast. The work on the big pier at Britannia Bay". The Ottawa Journal. February 23, 1900. Retrieved February 20, 2023.

- ^ "Britannia Island". Britannia: A History. Mike Kaulbars. 16 February 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Ontario Geographical Names database". Government of Ontario, Toronto. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ "Schematic diagram of the grounds of the Britannia Yacht Club" (PDF). Britannia Yacht Club, Ottawa. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- ^ Britannia Yacht Club: A History of Water, Place and People, 1887 – 2012. Ottawa: Britannia Yacht Club. 2013. pp. 25–31.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 344.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 60, 61.

- ^ a b c d e Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 127.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 127, 129, 421: "Assessment Rolls, Nepean Township, 1880 - 1940. Ottawa City Directory 1950/1960."

- ^ "Britannia the People's Playground". Worker's History Museum, Ron Kolbus Lakeside Centre, Ottawa. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 349.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 366.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 346.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 355.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 326.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 360.

- ^ "Britannia Amusement Park". Closed Canadian Parks. Chebucto Community Net. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Closed parks built or nurtured by transportation companies". Chebucto Community Net. Retrieved 6 September 2023.

- ^ Duffy, A (12 July 2020). "The Good Sewer: Why Ottawa's $232-million sewage storage tunnel is both an engineering marvel and an act of contrition". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 284.

- ^ Taylor & Kennedy 2017, p. 176, 282.

- ^ Ottawa Dept. of Public Works (August 1963). Proposals for Urban Renewal (Report). City of Ottawa. pp. 75–76.

- ^ "Flood proofing". Britannia Village Community Association. 21 February 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "Flood plain mapping - regulatory context". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "1-in-100 year interactive flood plain map with area-specific provisions". City of Ottawa. 3 April 2023. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ "1-in-350 year interactive flood plain map". City of Ottawa. 15 December 2022. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 18.

- ^ a b c d "Heritage Register". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 9 May 2022.

- ^ Ottawa Dept. of Public Works, Planning Branch (August 1967). Urban Renewal (Report). City of Ottawa. pp. 147, 151.

- ^ "Description of residential zones" (PDF). City of Ottawa. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Mapping of residential zones". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ Clark, Steve (2022). "More Homes Built Faster Act". Government of Ontario. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Ottawa is ready for a new zoning by-law". City of Ottawa. 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Interactive zoning map". City of Ottawa. 2024. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ "Ontario Heritage Act". Government of Ontario. 1990. Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ White-Crummey, Arthur (10 April 2024). "Remnants of Britannia's past as resort getaway up for heritage designation". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC.ca). Retrieved 21 July 2024.

- ^ Kotarba, Ashley; Walker, Kirsty (9 April 2024). "Presentation to Built Heritage Committee, City of Ottawa". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- ^ "Individual Designation under Part IV of the Ontario Heritage Act". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Changes to heritage properties". City of Ottawa. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Rachlis, L (18 July 2020). "Charming Cottages: Well-loved Britannia Homes Reflect Early History". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 8 May 2022.

- ^ Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 14.

- ^ Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 12.

- ^ Horwitz & Horwitz 1996, p. 13, 14.

- ^ "Queen Anne Architecture: History and Style". Study.com. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Warren, Ken; Caldwell, Tony (22 February 2024). "The ice swimmer: why Tom Heyerdahl carved a 25-meter swim lane in the frozen Ottawa River". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Britannia Winter Trail". Britannia Winter Trail Association, Ottawa. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ "Britannia Village community arts crawl". Facebook. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ "Bring-on-the-Bay". Nepean Sailing Club/Bushtukah, Ottawa. Retrieved 13 July 2024.

- ^ "IronMan Canada - Ottawa". IronMan. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "IronMan Canada – Ottawa 2025 Swim Loop". IronMan. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Warren, Ken (6 November 2023). "City honours Second World War hero Thomas George Fuller". Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 16 September 2024.

- ^ Blum, Andrew (23 June 2021). "The story of the former Olympian who designed the world's most beloved boat". Popular Science. Retrieved 18 September 2024.

Sources

edit- Taylor, E; Kennedy, J (2017) [1983]. Ottawa's Britannia. The Britannia Historical Association. p. 441. ISBN 978-0-88970-185-4.

- Horwitz, L; Horwitz, M (October 1996). "The Natural Charm of Britannia: A Heritage Character Statement". Britannia: A History. Mike Kaulbars. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

clean copy available from City of Ottawa, Heritage Department