Brain Damage is a 1988 American comedy horror film written and directed by Frank Henenlotter.[2] It stars Rick Hearst in his debut acting role as Brian, a young man who becomes acquainted with a talking parasite known as Aylmer (voiced by John Zacherle) that injects him with an addictive fluid that causes euphoric hallucinations; in return, Aylmer demands that Brian allow him to feed on the brains of other humans.

| Brain Damage | |

|---|---|

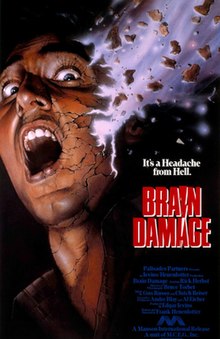

Promotional release poster | |

| Directed by | Frank Henenlotter |

| Screenplay by | Frank Henenlotter[1] |

| Produced by | Edgar Ievins[1] |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Bruce Torbet[1] |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

Production company | The Brain Damage Company[1] |

| Distributed by | Palisades Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 86 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Language | English[1] |

Produced on a budget of under $2 million, Brain Damage is the second feature film directed by Henenlotter, following Basket Case (1982).[3][4] Principal photography and filming on Brain Damage took place in Manhattan, New York City, in 1987. The film has been characterized as containing themes relating to both drug abuse and sexuality, though Henenlotter has downplayed such interpretations.[5] Along with special makeup and optical effects, the film makes use of mechanical puppetry and stop-motion animation.

Brain Damage received a limited theatrical release, premiering in select theaters in New York City on April 15, 1988, before being released in Los Angeles, California, the following month.[1] The film initially garnered mixed reviews, but quickly acquired a cult following after being released on home video. An uncut version of the film was later issued on DVD and Blu-ray.

Plot

editAfter suffering a brief illness, Brian experiences a powerful and comforting hallucination. He soon discovers that he has become host to a worm-like parasite that speaks perfect English and promises to give him a life free from worry. The hallucination was induced by a fluid injected from the parasite's mouth, through the back of Brian's neck and directly into his brain; the parasite offers Brian a steady supply of this fluid if "you'll take me for a walk." While under the influence of the "juice", Brian is incoherent and unaware of the world around him, allowing the parasite to kill and devour the brains of a night watchman in a junkyard, as well as a young woman at a nightclub. As Brian becomes addicted to the juice, he isolates himself from everything and everyone else in his life, which worries his girlfriend, Barbara, and his brother, Mike.

Brian awakens from his stupor long enough to learn about the murders. He is confronted in a courtyard outside his apartment building by his neighbor Morris, the previous owner of the parasite who dubbed it "The Aylmer",[a] and who states that it has changed hands hundreds of times across the globe since the Middle Ages. Morris, who fed Aylmer with animal brains, warns Brian that feeding it humans will make it too strong to resist. Horrified, Brian rents a flophouse room to wean himself off the fluid and starve Aylmer, but Aylmer gleefully informs him that his body chemistry has irrevocably changed, and that the pain of withdrawal will be too much for him to bear. Brian soon relents, now consciously attending Aylmer as he hunts for victims.

Returning to his apartment, Brian discovers that Mike and Barbara have begun a relationship; realizing that he cannot control himself or choose Aylmer's targets, Brian tries to warn them away before fleeing to the streets. Barbara follows and confronts him on the subway, where Aylmer kills her. Back at the apartment, Morris and his wife, Martha, hold Brian at gunpoint to steal Aylmer back; Aylmer attacks them. As he feeds on their brains, Brian begs for another injection of juice. Aylmer agrees, which distracts them long enough for Morris to regain consciousness, grabbing and crushing Aylmer during the injection process. This kills Aylmer and forces an overdose, leaving Brian in agony. Screaming and bleeding juice, he runs to his room, puts Morris's gun to his own head and fires.

The police arrive at the apartment building. Joined by Mike, they break down Brian's door—finding Brian, who stares blankly with a large, glowing hole in his forehead, emanating with light and long crackles of electricity.

Cast

edit- Rick Hearst as Brian[7]

- John Zacherle as Aylmer (voice)[8]

- Gordon MacDonald as Mike[7]

- Jennifer Lowry as Barbara[7]

- Theo Barnes as Morris Ackerman[7]

- Lucille Saint-Peter as Martha Ackerman[7]

- Vicki Darnell as Blonde In Hell[7][b]

- Joe Gonzalez as Guy In Shower[7]

- Bradlee Rhodes as Night Watchman[7]

- Michael Bishop as Toilet Victim[7]

- Beverly Bonner as Neighbor[7]

- Ari Roussimoff as Biker[7]

- Angel Figueroa as Junkie[7]

- Slam Wedgehouse as Punk[7]

- Michael Rubinstein as Bum[7]

Additionally, John Reichert and Don Henenlotter appear in the film as police officers, and Kenneth Packard and Artemis Pizarro appear as subway passengers.[7] Kevin Van Hentenryck makes a cameo appearance as "Man with Basket", a reference to his role as Duane Bradley in writer-director Frank Henenlotter's previous directorial work, Basket Case (1982).[10][11] Van Hentenryck had a crew cut at the time, and so wore a wig in order to match his hairstyle from Basket Case.[12]

Themes and interpretations

editDrug abuse

editBrain Damage was reportedly inspired by Frank Henenlotter's own cocaine addiction.[13]

In a 1988 interview with Henenlotter, Robert "Bob" Martin of Fangoria referred to the imagery of Aylmer's needle entering the back of Brian's neck as being invocative of drug abuse.[14] Henenlotter stated:

To me, the drug is a function of the plot and that's that. To see [Aylmer] as a metaphor for real drugs is a very narrow reading. The needle, the fluid—all of that simply moves the plot. In broader terms, [Aylmer] and all of that was simply a free ride, a way out: escapism. There are many other avenues for that besides drugs, but drug imagery was a simple, easy way of expressing that in a film.[14]

He likened the film to a "superficial adaptation of Faust",[14] a reading echoed by Los Angeles Times film critic Leonard Klady.[15]

Henenlotter rejected the notion that Brain Damage could be reasonably viewed as pro-drug in nature, stating, "If I planned to portray drugs as pleasurable, Brian wouldn't have lost everything that had meaning to him: his girlfriend, his life, all of it. If he's left alone with his pleasure, then what's the point?"[16] He then asserted that the film is neither "pro-drug" nor "anti-drug" in relation to real-life drug issues, but instead "a monster movie."[16]

Ahead of the film's release in Australia, Neil Jillett of The Age argued, "Brain Damage can be interpreted as an allegory about drug abuse, with the monster Aylmer standing in for heroin and Brian as an addict. The allegory is underlined by the use of the language of addiction in the film's dialogue. The allegory's message is that death is the only cure for heroin addiction."[17]

In 2017, journalist Michael Gingold wrote of the film that, "Appearing in the midst of the 'Just Say No' anti-drug campaign initiated by First Lady Nancy Reagan, the portrait of young man trying to kick a parasitical habit [...] was especially trenchant."[18]

Sexuality

editAs well as invoking drug abuse, Martin viewed Aylmer's needle entering Brian's neck as "a pretty grim, anti-sexual image".[14] In response to Martin's interpretation of the film's screenplay as being representative of a dread of sexual intercourse, Henenlotter stated:

Oh no, I don't think so at all! I don't agree with that at all. In an earlier version of the script, I had [Aylmer] so sexual in nature that it was dangerous; some of that carries over. But the thing is, any time someone mixes sex and horror, it's assumed that this is someone who hates sex or has a loathing of it. And that just isn't so.[14]

However, Henenlotter did acknowledge a sexual undertone to the film, adding:[14]

One of the guys at the lab was saying, "Oh my God, you're making some kind of weird statement here—you've got a monster that looks phallic, talking about his juice!" What can I say? It's obviously there. I didn't set out to put it there; that's simply what the imagery turned out to be, and I'm not about to change the imagery just to eliminate that.

Brain Damage makeup effects artist Gabe Bartalos later acknowledged the phallic nature of Aylmer's design, including its overall shape and veiny texture, and said that such elements were encouraged during the design process.[19]

In 2003, author Scott Aaron Stine noted Aylmer's design as being "a bit phallic", writing, "do I sense someone making a statement about male sexuality?"[20]

In 2017, academic Lorna Piatti-Farnell listed Brain Damage as being among a number of films released in the 1980s which highlight "a disturbing fascination with parasitic creatures and aliens crawling in and out of human mouths, leaving not only a disturbing sense of discomfort in the viewing audience, but also a good dose of raised highbrows and open mouths, as far as latent meaning of oral interactions are concerned".[22] Specifically, she writes that "the mouth lies at the center of a broader alien plot" in Brain Damage, in that Aylmer "uses ingestion [...] to gain control over its victims."[22]

Reviewing the film's 2017 Blu-ray release, Chuck Bowen of Slant Magazine wrote that "Brian's degradation suggests the crack epidemic of the '80s, and the threat and alienation of AIDS lingers over the outré, sexualized set pieces, especially when Brian cruises a nightclub called Hell and picks up a woman, who's murdered by Aylmer just as she's about to go down on Brian."[23]

In 2022, Henry Giardina of Into wrote that the film contains elements of homoerotic subtext and serves as an allegory for the transmasculine experience, citing Aylmer's phallic design and Brian waking up to find himself covered in blood (which Giardina likens to menstruation), as well as comparing Aylmer's "juice" to both semen and hormone replacement therapy (HRT).[21]

Production

editDevelopment and casting

editThe film's working title was Elmer the Parasite; Henenlotter conceived of the name Brain Damage when he "was literally writing the last scenes".[24] Initial plans by the New Jersey–based company Rugged Films—who had temporarily owned the distribution rights to Henenlotter's debut feature film Basket Case (1982)—to finance Brain Damage did not come to fruition.[24] Brain Damage was ultimately financed by Cinema Group, who invested $1.5 million into the production.[3]

In the original script, Aylmer speaks to Brian inside his head with a whispery voice that resembles Brian's own, and only utters grunting and groaning sounds when seen externally.[26] After deciding to have Aylmer's voice be "very sophisticated-sounding, articulate", Henenlotter contacted a vocal agent who offered a list of actors that might suit the part.[26] Henenlotter chose John Zacherle, a television horror host whom Henenlotter had watched in his youth, to voice Aylmer.[27] Later in the film's production, Henenlotter called Zacherle to ask if he wanted his name to be billed in the credits as "John Zacherle" or "John Zacherley", and discovered that Zacherle was a member of the Screen Actors Guild (SAG).[25] As Brain Damage was a non-SAG production, Zacherle went uncredited for his voice role, in order to avoid fines or expulsion from SAG.[25] According to Bartalos, Zacherle visited the set twice.[28]

Rick Hearst, Gordon MacDonald, and Jennifer Lowry were all first-time actors, and Brain Damage remains Lowry's only film credit as an actress.[26] Henenlotter wanted Hearst to have "some kind of edge" as Brian, and so he had a scar added to Hearst's lower lip during filming.[29] Hearst later called this "the funniest choice that I think Frank made for me," stating that Henenlotter felt that he "needed to have that as part of the character, otherwise I'd look too pretty. And I was like, 'that did it?' I mean, you could've scarred me [on the cheek], I mean, I could've had part of an ear off..."[29]

The crew of Brain Damage included veterans of Basket Case and 1987's Street Trash (such as Jim Muro, who was Steadicam operator on all three films, as well as the director of Street Trash); seven Brain Damage crew members had also worked on 1988's Slime City (including Muro and Slime City director Greg Lamberson, the latter of whom served as first assistant director on Brain Damage).[30]

Filming

editPrincipal photography on Brain Damage began on January 21, 1987,[1] and took place over the course of eight weeks.[31] Filming took place in New York City, New York,[32] over two months.[26] The primary location for the shoot was a building on West 33rd Street in Manhattan that had formerly housed belt manufacturing and sign painting businesses.[26] According to Ievins and Lamberson, the first floor of the building was an equipment rental house operated by Mike Spera, from which the production rented its equipment; the second floor was rented out as living space for Bartalos and mechanical effects artist David Kindlon; and the fourth floor was used for filming.[33]

Brian's apartment, the Hell nightclub, and the courtyard were all constructed sets built in the West 33rd Street building.[34] The junkyard sequence was filmed at Statewide Auto Parts, a junkyard then located at 1256 Grand Street, Brooklyn, that was owned by Muro's father.[35] The scene in which Aylmer kills the blonde woman from the nightclub was shot in the upper boiler room of the Film Center Building, without authorization from the building's management.[36] The dinner date between Brian and Barbara was filmed at the restaurant Le Madeleine at 403 West 43rd Street, which has since closed and been replaced by Bea Restaurant & Bar.[37] Following the date, Brian is seen walking down St. Mark's Place between Second and Third Avenue.[38]

The interior hotel room to which Brian takes Aylmer in an attempt to wean himself off of Aylmer's fluid was a constructed set; the exteriors of the location were shot at the Sunshine Hotel at 245 Bowery in no longer than one hour, as Lamberson and sound editor Joe Warda were told by the hotel's management that they could shoot there for one hour for $200, and that each additional hour would cost an additional $200.[39]

Special effects

editAl Magliochetti, who would serve as stop-motion animator and optical effects artist on Brain Damage,[40] received the screenplay for the film from Henenlotter, and lent it to Bartalos.[41] At the time, Magliochetti and Bartalos were working together on the 1986 film Spookies.[41] Bartalos and Arnold Gargiulo (for whom Bartalos was working as an assistant), met with Henenlotter and producer Edgar Ievins to discuss the effects work that would be involved in Brain Damage.[42] Though Gargiulo was uninterested in the project after having the plot described to him, Bartalos agreed to join the production.[42]

Magliochetti has recalled Henenlotter wanting Aylmer's design to resemble "a black dildo",[43] while Bartalos has stated that discussion of the design involved mention of a phallus and "a turd", as well as a cartoonish mouth and eyes.[44] During the process of creating a sculpt of Aylmer, suction cups were integrated into its design.[45] There were two primary, cable-operated puppets of Aylmer created for the film: one "actual size" puppet, and an oversized puppet used for close-up shots.[46]

For the scene in which Aylmer kills the junkyard watchman, Bartalos built a "half-creature" that was attached to prosthetics on actor Bradlee Rhodes's head.[47] Kindlon rigged a mechanical device that allowed the creature to move independently of the actor playing the guard.[47] The sequence also features a stop-motion model of Aylmer that is seen eating the watchman's brain after he drops to the ground;[48] this same model is again seen later in the film, during a shot wherein Aylmer leaps onto a man sitting in a bathroom stall.[48] This Aylmer model was constructed using a "cold" (or unbaked) inner foam and an outer layer made of "hot" (baked) latex foam rubber.[48]

A calf brain purchased from a deli was used in the shots in which Aylmer's fluid can be seen coating Brian's brain.[49] The electricity seen crackling in these shots was animated by Magliochetti.[49]

Using a plaster cast of Hearst, multiple models of Brian's head were sculpted for the film,[50] as well as a fiberglass body that was constructed for the "zipper scene"[51][52] in which Aylmer emerges from the fly of Brian's pants into the mouth of the blonde woman from the nightclub.[51] A collapsible model of Aylmer was inserted into actress Vicki Darnell's mouth and filmed being pulled out; using reverse motion photography, the final footage appears to show Aylmer entering her mouth.[47] For the subsequent shot of Aylmer exiting her mouth with a mouthful of brain matter, Bartalos sewed calf brains to a model of Aylmer, and Darnell was provided with Binaca breath spray before the take began.[53] Henenlotter estimated that about 15 to 20 minutes of coverage was filmed for the scene.[54]

To achieve the desired velocity of the blood and brain matter gushing out of the side of Brian's head during one of his withdrawal-induced hallucinations, the effects team placed Hearst on a metal brace on an angle of about 45°, with the camera at a matching angle.[55] After filming Hearst screaming at said angle, the crew filmed the same shot without Hearst in frame, and dumped fake blood and gore down a large piece of heat ducting; the two shots were then composited together, making it appear as though the blood is pouring out of Brian's head.[55]

The shots of Aylmer emerging from Brian's mouth on the subway were animated by Magliochetti.[56] The effect involved Magliochetti lining up an articulated model of Aylmer with a projection of the relevant frames from the film; he then animated Aylmer frame-by-frame using stop-motion, cut the Aylmer model out of each the resulting frames using an X-Acto knife, and glued each cut-out to animation cels that he then lined up to the film footage.[56]

The shot of light beams shining out of Brian's bedroom window in the final scene of the film was accomplished using a miniature brick façade of a side of the apartment building, fashioned together by Magliochetti with parts from a dollhouse supply store affixed to a plank of wood.[57] Magliochetti stood behind the miniature and waved around a slide projector, causing flashing light to be projected through the miniature window.[57]

Post-production

editBrain Damage was edited at night at the Film Center Building, which allowed low-budget productions to utilize its film and sound editing facilities after hours for free, so long as they "cleaned the space by 8 a.m., when the paying customers arrived".[58] James Kwei, who had invested money in Basket Case's production and worked nights at the Film Center Building, served as an editor on Brain Damage.[59] The first cut of Brain Damage was around 66 minutes in length, which led Henenlotter and Kwei to adjust the pacing in order to extend its running time.[59]

Release

editPre-release

editIn the interview with Martin, Henenlotter stated that distributors expected the "zipper scene" to be considered too graphic for an R rating by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), resulting in the scene being edited down.[54] He added, "Apparently, the MPAA won't allow us to show Brian biting into her brain. I don't know yet, though. There's still a big question mark around some of this."[54] The film was edited down for an R rating for its initial theatrical release.[60]

The release of Brain Damage was accompanied by the publication of a novelization written by Martin, limited to 1,000 signed and numbered copies.[60] The book was published in hardcover under the Broslin Press imprint.[60]

Theatrical

editBrain Damage premiered in New York City on April 15, 1988,[1][3] opening at Cine 1 and the Lyric Theatre.[61] It was later released in Los Angeles, California, on May 20, 1988.[1] Hearst went to a showing of the film at Grauman's Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood, and later recalled that he, his family, and several friends were the only people in attendance.[62]

The film was distributed theatrically in the United States by Palisades Entertainment.[26] It was released in Australia on November 25, 1988, opening at The Capitol in Melbourne.[17]

Brain Damage was screened out of competition at the 1988 Toronto International Film Festival in Toronto, Canada, as part of the festival's "Midnight Madness" series.[63][64]

Home media

editIn July 1988,[65] Brain Damage was released on Betamax and VHS[66][67][68] by Paramount Home Entertainment.[69] The "zipper scene" remained truncated for the VHS release, and would not be made available uncut until the film was released on DVD.[36]

In 2007, the uncut version of the film was released on DVD by Synapse Films.[60][70]

On May 9, 2017, Arrow Video released a restoration of the film completed by Deluxe, London, on Blu-ray and DVD.[23][71] The release includes such bonus features as a retrospective audio commentary by Henenlotter and interviews with the cast and crew (both produced for the release), as well as the animated short film Bygone Behemoth, which features Zacherle in his final on-screen film credit.[71][23]

In 2022, Brain Damage was made available for streaming on the streaming service Fandor.[72]

Reception

editContemporary reviews

editJoe Kane, writing for the New York Daily News, called Brain Damage "one of the year's more original fright exercises, blending visceral shocks with twisted black humor and low-budget psychedelic tableaux to rival the old Joshua Light Show."[73] The Los Angeles Times' Leonard Klady referred to the film as "a veritable crazy quilt of ideas that manages to engage our attention while our heads continue to dart away from the shocking images on screen".[15] John Brooker of the Cheshunt and Waltham Mercury called the film "a charming little chiller", and "a compelling mix of wacky humour and gory special effects".[74]

The New York Times' Walter Goodman called Brain Damage a "brainless movie", criticizing the acting and special effects.[61] Lou Cedrone of The Baltimore Evening Sun wrote, "The producers did try to be funny, but their film is more revolting than it is amusing", and concluded that, "At heart, it is little more than a meaningless exercise in slime."[75] The Age's Neil Jillett called it "a comedy in somewhat poor taste", and wrote, "While Brain Damage is not advocatory [of drug abuse], its message is hardly helpful to the anti-drug campaign."[17]

Retrospective assessments

editIn a 2013 interview with Fangoria, Henenlotter said that the film was initially disliked, stating that, "Even the Basket Case fans didn't embrace it... they just wanted another Basket Case! People loved Basket Case and they just want you to make the same film over and over again."[76] However, he noted that appreciation for the film grew after it was released on home video.[76] The film has been characterized as having acquired a cult following, with Kane calling both Basket Case and Brain Damage "cult faves" in 1989.[77]

In 2017, Slant Magazine's Chuck Bowen called the film a "gnarly gem of 1980s-era punk horror".[23] In 2022, Matthew Thrift of the British Film Institute included Brain Damage on his list of "10 great body horror films".[78]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 67% based on 15 critics, with an average rating of 6.20/10.[79] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 61 out of 100, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[80]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The film's end credits, as well as promotional materials and home media releases, spell the creature's name as "Elmer". However, in the film, Morris states that he did not name the creature "Elmer", but instead, "Aylmer. A-y-l-m-e-r. An Old English word meaning, 'the awe-inspiring famous one'".[6]

- ^ Named "Roxie" in the screenplay.[9]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Brain Damage". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ The Staff and Friends of Scarecrow Video (2004). The Scarecrow Movie Guide. Seattle: Sasquatch Books. pp. 630–723. ISBN 1-57061-415-6.

- ^ a b c Kane, Joe (April 14, 1988). "From "Basket Case" to 'Brain Damage'". New York Daily News. New York, New York. p. 60. Retrieved November 29, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Paglia, Bernice (September 6, 1989). "'Basket Case' gets shot in Plainfield". The Courier-News. Bridgewater, New Jersey. Retrieved November 29, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ (Martin 1988a, pp. 52–53)

- ^ Henenlotter, Frank (director) (1988). Brain Damage (Motion picture). Arrow Video. Event occurs at 40:27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Lentz III, Harris M. (1994). Science Fiction, Horror & Fantasy Film and Television Credits, Supplement 2: Through 1993. McFarland & Company. p. 371. ISBN 978-0899509273.

- ^ TV Guide

- ^ (Gingold 2017a, pp. 10–11)

- ^ Van Heerden, Bill (2008). Film and Television In-Jokes: Nearly 2,000 Intentional References, Parodies, Allusions, Personal Touches, Cameos, Spoof and Homages. McFarland & Company. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-7864-3894-5.

- ^ Hallenbeck, Bruce G. (2009). Comedy-Horror Films: A Chronological History, 1914–2008. McFarland & Company. p. 163. ISBN 978-0786433322.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 38:48–39:22.

- ^ Towlson, Jon (2014). Subversive Horror Cinema: Countercultural Messages of Films from Frankenstein to the Present. McFarland & Company. p. 186. ISBN 978-0786474691.

- ^ a b c d e f g (Martin 1988a, p. 52)

- ^ a b Klady, Leonard (May 24, 1988). "Movie Reviews : "Brain Damage" a Bizarre Crazy Quilt of Ideas". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ a b (Martin 1988a, p. 53)

- ^ a b c Jillett, Neil (November 22, 1988). "Keeping within the guidelines for films". The Age. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. p. 14. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ (Gingold 2017a, p. 7)

- ^ a b (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 11:14–11:27.

- ^ a b Stine 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b Giardina, Henry (August 19, 2022). "This Cult Film Has Male Nudity, Trans Allegory, and an Extremely Phallic Puppet". Into. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Piatti-Farnell, Lorna (2017). Consuming Gothic: Food and Horror in Film. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 42. ISBN 978-1137450500.

- ^ a b c d Bowen, Chuck (May 23, 2017). "Blu-ray Review: Frank Henenlotter's Brain Damage on Arrow Video". Slant Magazine. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ a b (Gingold 2017a, p. 10)

- ^ a b c (Gingold 2017a, p. 14)

- ^ a b c d e f (Gingold 2017a, p. 11)

- ^ Gingold 2017a, p. 11, 14.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 12:35–12:49.

- ^ a b (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 21:45–22:52.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 15:02–17:07 and 18:08–18:49.

- ^ Ferrante 1987, p. 37–38.

- ^ Ferrante 1987, p. 36.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 26:58–27:18 and 28:24–28:33.

- ^ (Gingold 2017b): Event occurs at 1:33–1:45.

- ^ (Gingold 2017b): Event occurs at 6:01–6:42.

- ^ a b (Gingold 2017b): Event occurs at 3:07–3:46.

- ^ (Gingold 2017b): Event occurs at 3:55–4:15.

- ^ (Gingold 2017b): Event occurs at 4:29–4:55.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 34:11–36:45.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 29:30–29:42.

- ^ a b (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 6:05–6:30.

- ^ a b (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 3:26–5:13.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 8:28–8:33.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 8:34–8:46 and 10:24–10:33.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 9:58–10:01.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 10:49–10:57.

- ^ a b c Ferrante 1987, p. 39.

- ^ a b c (Drenner & Magliochetti 2017b): Event occurs at 1:28–2:02.

- ^ a b (Drenner & Magliochetti 2017b): Event occurs at 2:04–2:21.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 24:46–24:54.

- ^ a b Ferrante 1987, p. 38–39.

- ^ (Martin 1988b, p. 47): "With the exception of the zipper scene?"

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 45:23–46:13.

- ^ a b c (Martin 1988b, p. 47)

- ^ a b c (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 33:13–34:07.

- ^ a b (Drenner & Magliochetti 2017b): Event occurs at 0:33–1:21.

- ^ a b (Drenner & Magliochetti 2017b): Event occurs at 5:06–5:40.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 41:34–42:11.

- ^ a b (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 42:12–44:20.

- ^ a b c d (Gingold 2017a, p. 15)

- ^ a b Goodman, Walter (April 15, 1988). "Review/Film; Brain Drain, in 'Damage'". The New York Times. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ (Drenner et al. 2017a): Event occurs at 47:27–47:43.

- ^ Schnurmacher, Thomas (September 10, 1988). "'Gold patrons' find price of movie tickets going up and up". The Gazette. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. p. H-7. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wilner, Norman (August 31, 2016). "Scream and scream again reboots are horror's bleeding edge". Now. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Barsky, Larry (August 1988). "Video Chopping List". Fangoria. Vol. 8, no. 76. Starlog Group, Inc. p. 13. ISSN 0164-2111. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ Cidoni, Mike (July 8, 1988). "Low-budget 'Positive I.D.' is genuine thriller". Battle Creek Enquirer. Battle Creek, Michigan. Retrieved November 29, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Weiner, David J.; Gale, Thomson (1991). Video Hound's Golden Movie Retriever, 1991. Visible Ink Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-8103-9404-9.

- ^ Bleiler, David, ed. (1999). TLA Film and Video Guide 2000–2001: The Discerning Film Lover's Guide. St. Martin's Griffin. p. 73. ISBN 978-0312243302.

- ^ Stine 2003, p. 57.

- ^ "Brain Damage (DVD)". synapse-films.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Coffel, Chris (April 26, 2017). "Exclusive Look at Arrow Video's Upcoming "Brain Damage" Blu-ray!". Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

- ^ Welcome to Gritty NYC | Now Showing on Fandor. Fandor on YouTube. January 19, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ Kane, Joe (April 13, 1988). "Really, Dear, I Love You for Your Brain". New York Daily News. New York, New York. p. 38. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brooker, John (February 26, 1988). "Video Scene | Brains for dinner and tea too!". Cheshunt and Waltham Mercury. Cheshunt, Hertfordshire, England. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Cedrone, Lou (May 10, 1988). "'Little Nikita' is the best of several unremarkable new movies". The Evening Sun. p. E5. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Thompson, Tristan (May 31, 2013). "The Monster Movie Memories of a Brain-Damaged Basket Case: In conversation with Frank Henenlotter". Fangoria. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ^ Kane, Joe (August 9, 1989). "What we have here is monstress". New York Daily News. New York, New York. p. 37. Retrieved December 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Thrift, Matthew (September 8, 2022). "10 great body horror films". British Film Institute. Retrieved December 5, 2022.

- ^ "Brain Damage". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ^ "Brain Damage Reviews". Metacritic. Red Ventures. Retrieved November 28, 2022.

Bibliography

edit- Drenner, Elijah (Director and Editor); Ievins, Edgar (Interviewee); Bartalos, Gabe (Interviewee); Magliochetti, Al (Interviewee); Lamberson, Greg (Interviewee); Frye, Dan (Interviewee); Hearst, Rick (Interviewee; as Rick Herbst); Kwei, James (Interviewee) (2017a). Listen to the Light: The Making of Brain Damage (Making-of documentary). Arrow Video.

- Drenner, Elijah (Director and Editor); Magliochetti, Al (Interviewee) (2017b). Animating Elmer (Featurette). Arrow Video.

- Ferrante, Tim (December 1987). "At Long Last: Brain Damage". Fangoria. Vol. 7, no. 69. Starlog Group, Inc. ISSN 0164-2111. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- Gingold, Michael (2017a). "A Mind and a Terrible Thing: The Story of Brain Damage". Brain Damage (PDF) (Booklet). Cant, Ewan (Disc and Booklet Produced by). Arrow Video. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 5, 2022. Retrieved December 4, 2022.

- Gingold, Michael (Director and Producer) (2017b). Elmer's Turf: The NYC Locations of Brain Damage (Featurette). Arrow Video.

- Martin, Robert (February 1988a). "Bully for Brain Damage". Fangoria. Vol. 8, no. 71. Starlog Group, Inc. ISSN 0164-2111. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- Martin, Robert (March 1988b). "Life with Elmer (Part Two)". Fangoria. Vol. 8, no. 72. Starlog Group, Inc. ISSN 0164-2111. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

- Stine, Scott Aaron (2003). The Gorehound's Guide to Splatter Films of the 1980s. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0786415328. Retrieved November 29, 2022.

External links

edit- Brain Damage at IMDb