Bouar is a market town in the western Central African Republic, lying on the main road from Bangui (437 km) to the frontier with Cameroon (210 km). The city is the capital of Nana-Mambéré prefecture, has a population of 40,353, while the whole sous-préfecture has a population of 96,595 (2003 census). Bouar lies on a plateau almost 1000m above sea level and is known as the site of Camp Leclerc, a French military base.

Bouar

Buar[1] | |

|---|---|

Bouar | |

| Coordinates: 5°57′N 15°36′E / 5.950°N 15.600°E | |

| Country | Central African Republic |

| Prefecture | Nana-Mambéré |

| Government | |

| • Sub-prefect | Jean Michel Bouaka[2] |

| • Mayor | Dieu-Beni Massina[3] |

| Elevation | 1,046 m (3,432 ft) |

| Population (2012)[4] | |

• Total | 39,205 |

About seventy groups of megaliths lie in the town and to its north and east. The Bouar Megaliths, dating back to the very late Neolithic Era (c. 3500–2700 BC) were added to the UNESCO World Heritage Tentative List on April 11, 2006 in the Cultural category.[5]

The town's name comes from the Gbaya word for bean, hbouar.[6]

History

editHundreds of granite megaliths around Bouar were erected during the Late Stone Age by an ancient farming society. These stone megaliths are nowadays known as tanzunu in Gbaya.[7]

The Gbaya people settled in the region around the 1500s.[7] The settlement of Bouar itself was founded circa 1840 by chief Bogbafeï on the site of a bean field. His grandson, Mbarta, served as the chief between 1904 and 1916 and nowadays is remembered as a local hero.[6][8]

In 1882, France invaded Central Africa and 1894, the borders of French Congo encompassed Bouar. In 1911, the area around Bouar was ceded by France to Germany under the terms of the Morocco-Congo Treaty, becoming part of the German colony of Neukamerun until it was reconquered by the French during World War I.[9] The Germans eventually settled in the town around Christmas of 1913, where they constructed a military post and a road.[6] In 1928, the town became part of the French colony of Ubangi-Shari.

The colonial town centre was occupied and burned down in the late 1920s by Gbaya rebels during the Kongo-Wara rebellion. This was the most significant period in which the Gbaya population and others resisted French colonial rule in Ubangi-Shari.

In 1948, the administrative centre of Ouham-Pendé prefecture was moved from Bozoum to Bouar. Later, the western part of the prefecture would become Nana-Mambéré prefecture with Bouar as its capital, while Bozoum would become the capital of the remaining Ouham-Pendé prefecture.[6] Electricity was installed in Bouar in 1952.[10] In 1960 the colony became independent as the Central African Republic.

-

The ancient stone megaliths of Bouar depicted on a 1967 stamp.

-

A portrait of chief Mbarta as a "Hero of Bouar" in the town's museum.

-

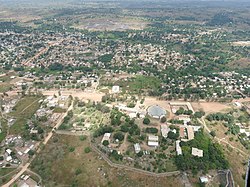

A view of Bouar in 2015.

-

Children celebrating International Women's Day in 2016.

Civil war

editOn 28 March 2013 Bouar was captured by Séléka rebels.[11] On 26 October 2013 Bouar was attacked and captured by Anti-balaka militias resulting in more than 20 deaths.[12] As of February 2014 the town and region around Bouar were experiencing ethnic cleansing, principally against Muslim civilians.[13] A French journalist, Camille Lepage, was also killed and her body found in the car of Anti-balaka troops in the Bouar region in May, 2014.[14][15]

On 18 September 2017 city was recaptured by FACA from Anti-balaka.[16] On 20 December 2020 parts of city were captured by rebels from Coalition of Patriots for Change.[17] On 27 December entire city was captured by rebels.[18] After many clashes it was recaptured by government forces on 8 February 2021.[19]

Places of worship

editAmong the places of worship, they are predominantly Christian churches and temples : Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Central African Republic (Lutheran World Federation), Evangelical Baptist Church of the Central African Republic (Baptist World Alliance), Roman Catholic Diocese of Bouar (Catholic Church).[20] There are also Muslim mosques.

Climate

editKöppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies Bouar’s climate as tropical wet and dry (Aw).[21]

| Climate data for Bouar (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 31.4 (88.5) |

32.6 (90.7) |

31.9 (89.4) |

30.1 (86.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

27.2 (81.0) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.0 (78.8) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

29.9 (85.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

29.1 (84.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 24.4 (75.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.1 (71.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.9 (73.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

23.9 (75.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 17.8 (64.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

18.5 (65.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.9 (0.07) |

13.0 (0.51) |

43.5 (1.71) |

109.9 (4.33) |

144.2 (5.68) |

165.2 (6.50) |

223.5 (8.80) |

277.5 (10.93) |

266.4 (10.49) |

196.1 (7.72) |

18.3 (0.72) |

2.1 (0.08) |

1,461.7 (57.55) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 0.1 | 1.5 | 4.9 | 9.2 | 12.0 | 13.0 | 16.4 | 18.0 | 18.2 | 15.0 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 110.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (daily average) | 34.4 | 39.6 | 57.0 | 71.6 | 77.8 | 80.8 | 82.4 | 82.9 | 80.4 | 77.5 | 61.7 | 41.1 | 65.6 |

| Source: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Buar (Variant) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ^ Oubangui Medias, Oubangui Medias. "Centrafrique : Décrets portant nomination des Gouverneurs, des Préfets et des Sous-Préfets". oubanguimedias.com. Oubangui Medias. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ Ndeke Luka, Ndeke Luka. "Face à l'insalubrité dans la ville de Bouar, Dieu-Beni Massina lance des initiatives". radiondekeluka.org. Radio Ndeke Luka. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "World Gazetteer". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11.

- ^ Les mégalithes de Bouar - UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- ^ a b c d Degras, Alain (2012). Akotara: Un triptyque consacré aux Gbayas du Nord-Ouest Centrafricain (PDF) (in French). Bouar: Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. pp. 20, 62. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2022.

- ^ a b David, Nicholas (1982). "Tazunu: Megalithic Monuments of Central Africa". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 17 (1): 43–77. doi:10.1080/00672708209511299.

- ^ "Marie-Noëlle Koyara célèbre la fête de noël en différé avec les enfants de Bouar" (in French). Agence Centrafricaine de Presse. 31 December 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2022.

- ^ Bradshaw, Richard; Fandos-Rius, Juan (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic (New ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 137. ISBN 9780810879911.

- ^ Rius, Juan Fandos; Bradshaw, Richard (2016). Historical Dictionary of the Central African Republic. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 251. ISBN 9780810879928.

- ^ "Central African Republic Situation Report No. 9 (as of 28 March 2013)". 28 March 2013.

- ^ "Pillay Warns Violence In Central African Republic May Spin Out Of Control". 8 November 2013.

- ^ MSF, Trapped By Violence in Bouar, Central African Republic, (video) February 2014, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LfQuJnpVZvE

- ^ Camerpost, Centrafrique : une journaliste française « assassinée » dans la région de Bouar – 13/05/2014, http://www.camerpost.com/centrafrique-une-journaliste-francaise-assassinee-dans-la-region-de-bouar-13052014/ Archived 2014-06-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Paris confirms French journalist murdered in CAR, DW, Date 13.05.2014, http://www.dw.de/paris-confirms-french-journalist-murdered-in-car/a-17633357

- ^ "Centrafrique : panique à Bouar, les Faca font des tirs". 19 September 2017.

- ^ "RCA : Bouar, la barrière de Yolé occupée par les rebelles". 20 December 2020.

- ^ "RCA : la ville de Bouar, tombée aux mains des rebelles le jour de vote, est toujours sous le choc". 30 December 2020.

- ^ "RCA : Bouar, la ville est désormais sans rebelles". 8 February 2021.

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 531-532

- ^ "Climate: Bouar - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ^ "Bouar Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.