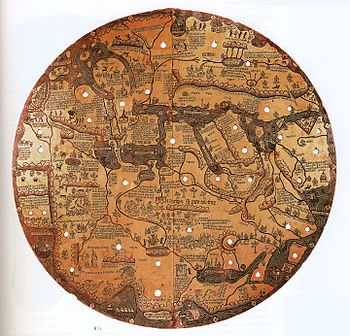

Mainly a decoration piece, the Borgia map is a world map made sometime in the early 15th century, and engraved on a metal plate. Its "workmanship and written explanations make it one of the most precious pieces of the history of cartography".[1]

History

editThe year when the Borgia map was created is unknown. One source argues that the map must date from sometime before 1453.[2] Another source suggests the map was made c.1450.[3]

In the late 18th century the artifact found its way into an antique shop, from where it became part of the collection of Cardinal Stefano Borgia. The script appearing on the map identifies it as being south German. However, nothing about the authorship of the Borgia map is known. The emphasis on history, and the traditional nomenclature (names/terms/principles) suggests that it was originally designed as a historical map, for use in a library or a school.[4]

Details

editOn the Borgia map, the Garden of Eden is positioned near India superior - the mouth of the Ganges, and is portrayed as a land of marvels and precious stones. It is also quite close to China, a country which is represented by tiny figures collecting silk from the trees.[5]

The Babylonian, Alexandrian, Carthaginian and Roman Empires are emphasized on the map in an orderly sequence. Of the chaotic Italian state at the time, the mapmaker comments that "Italy, beautiful, fertile, strong and proud, from lack of a single lord, has no justice". Special mentions are made of various Crusades including: Charlemagne's campaign in the Iberian Peninsula, crusading in northeastern Europe, Africa, and Nicopolis, and the "future" threat of the Gog and Magog, who are described specifically as "Jews". The map has a well crafted design, and was made to last a long time.[6]

The Borgia map includes a legend referring to Ebinichibel, who is described as "the Saracen Ethiopian king with his dog-headed people". This is one of the many examples of where the blasphemous extremes of the world were depicted as monstrous races, who were yet to be converted by Christian missionaries.[7]

References

edit- ^ Róna-Tas, András (1982). Chuvash studies. Harrassowitz. p. 185. ISBN 978-3-447-02273-6. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Falchetta, Piero (2006). Fra Mauro's world map: with a commentary and translations of the inscriptions. Brepols. p. 37. ISBN 978-2-503-51726-1. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Seaver, Kirsten A. (2004). Maps, myths, and men: the story of the Vínland map. Stanford University Press. pp. 210. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Edson, Evelyn (2007). The world map, 1300-1492: the persistence of tradition and transformation. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8018-8589-1. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Scafi, Alessandro (2006). Mapping paradise: a history of heaven on earth. University of Chicago. ISBN 978-0-226-73559-7. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Edson, Evelyn (2007). The world map, 1300-1492: the persistence of tradition and transformation. The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-8018-8589-1. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

- ^ Jacob Pandian, Susan Parman (2004). The making of anthropology: the semiotics of self and other in the Western Tradition. Vedams eBooks (P). p. 67. ISBN 978-81-7936-014-9. Retrieved February 24, 2012.

Further reading

edit- Nordenskiöld, A. E. (1891) "An account of a copy from the 15th century of a Map of the World engraved on metal, which is preserved in cardinal Stephan Borgia's museum at Velletri; copied from Ymer, 1891". Stockholm: A. L. Norman (this mappemonde was later acquired by the John Rylands Library, Manchester)