The Bleiburg repatriations (see terminology) were a series of forced repatriations from Allied-occupied Austria of Axis-affiliated individuals to Yugoslavia in May 1945 after the end of World War II in Europe. During World War II, Yugoslavian territory was either annexed or occupied by Axis forces, and as the war came to end, thousands of Axis soldiers and civilian collaborators fled Yugoslavia for Austria as the Yugoslav Army (JA) gradually retook control. When they reached Austria, in accordance with Allied policy, British forces refused to take them into custody and directed them to surrender to the JA instead. The JA subsequently subjected them to death marches back to Yugoslavia, where those who survived were either subject to summary executions or interned in labor camps, where many died due to harsh conditions. The repatriations are named for the Carinthian town of Bleiburg, where the initial British refusal to accept the surrenders occurred, and from which some repatriations were carried out.

| Part of the aftermath of World War II in Yugoslavia | |

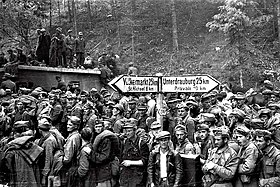

World War Two prisoners of war at Bleiburg, Austria (1945) | |

| Date | May 1945 |

|---|---|

| Location | March to Austrian border and back through Yugoslavia |

| Type | Military operations |

| Motive | Revenge for atrocities, collaboration and occupation |

| Target | Mainly Ustaše, Slovene Home Guard and German prisoners of war and Croat, Bosniak, and Slovene civilians associated with atrocities and collaboration |

| Participants | Yugoslav Partisans |

| Outcome | Summary executions, massacres, death marches |

| Deaths | c. 70,000–100,000 |

| Litigation | None, officially suppressed |

On 3 May 1945, the government of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a fascist puppet state established in German-occupied Yugoslavia which had undertaken genocidal campaigns against its minority populations, reducing their numbers by the hundreds of thousands, decided to flee to Austria. They initiated the evacuation by ordering the Croatian Armed Forces (HOS) to move there as soon as possible, in order to surrender to British forces. The Axis-aligned Slovene leadership issued similar orders to the Slovene Home Guard on the same day. These forces, accompanied by civilians, joined the German Army Group E and other Axis units in withdrawal; the latter included the XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps and the remnants of the Montenegrin Chetniks organized in the HOS-commanded Montenegrin National Army.

In the week after the German Instrument of Surrender, which marked the formal end of World War II in Europe, collaborationist forces in Yugoslavia continued to battle the Partisans to avoid encirclement and keep escape routes open. The Slovene-led columns fought their way to the Austrian border near Klagenfurt on 14 May. Their surrender was accepted by the British and they were interned in the nearby Viktring camp. When one of the columns of fleeing HOS troops, who were intermingled with civilians, approached the town of Bleiburg on 15 May, the British refused to accept their surrender. They directed them to surrender to the Partisans, which the HOS leadership did after short negotiations. Other Axis prisoners in British captivity were repatriated to Yugoslavia in the following weeks. The repatriations were canceled by the British on 31 May, following reports of massacres in Yugoslavia. The Yugoslav authorities moved the prisoners on death marches throughout the country to internment and labor camps. Mass executions were carried out, the largest of which were in Tezno (estimated at 15,000 Croatian prisoners of war),[1] Kočevski Rog, Huda Jama and Macelj. In the ensuing Communist rule in Yugoslavia, these massacres and other abuses after the repatriations were a taboo topic and information about the events was suppressed. Public and official commemoration of the victims, which included civilians, did not begin until several decades later.

Historians have been unable to accurately ascertain the number of casualties during and after the repatriations; exact numbers have been the subject of much debate, and assessments are typically in the ranges of tens of thousands. Historians and investigations in Slovenia and Croatia indicate that most of the victims were members of Croatian, Slovene, Montenegrin and Serb collaborationist armed forces.[2][3][4] Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, an annual commemoration for the victims has been held in Bleiburg, but has drawn considerable controversy due to Ustaše symbols at the event. Croatian authorities have variously either endorsed that commemoration or initiated other commemorations in Slovenia, while the Austrian authorities have increasingly made moves to prevent it from further happening.

Terminology

editIn Croatia simply Bleiburg is the most commonly used term for the events, followed by Bleiburg Tragedy, Bleiburg massacre, Bleiburg crime and Bleiburg case.[5][6][7] The term 'tragedy' has also been used in English-language works of authors of Croatian origin.[8][9][10] The term Way of the Cross (Croatian: Križni put), which equates the events with Jesus' crucifixion, is a common subjective term, used mostly by Croatians, regarding the events after the repatriations.[5] The latter have been described as "death marches".[11][12] The term death marches, unlike many others, is used by international literature on the topic, and Croatian historian Martina Grahek Ravančić discusses the topic of "Bleiburg and the Death Marches".[13]

In Slovenia, the term Bleiburg Tragedy (Pliberška tragedija) is the most commonly used, while Bleiburg Massacre (Slovene: Pliberški pokol) and Viktring tragedy (Vetrinjska tragedija) are less employed.[14] Viktring was a British camp where the largest number of Slovene prisoners were interned before repatriations took place.[15]

Background

editWhen World War II broke out in 1939, the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia declared its neutrality.[16] By the beginning of 1941, most of its neighbors joined the Tripartite Pact.[17] Yugoslavia came under strong pressure to join the Axis and the Yugoslav government signed the Pact on 25 March 1941, the year that Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union. But demonstrations broke out in Belgrade against the decision, and on 27 March, the opposition overthrew the government in a coup d'état. The new Yugoslav government refused to ratify the signing of the Tripartite Pact, though it did not rule it out. Adolf Hitler reacted by launching the invasion of Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, allied with forces of Italy and Hungary.[18]

On 10 April, German troops entered Zagreb and on the same day, the German-Italian puppet state, the Independent State of Croatia (Croatian: Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), was installed. The Ustaše were put in power by Hitler who appointed Ante Pavelić as the leader (Poglavnik) of the NDH.[19] Yugoslavia capitulated to the Axis powers on 17 April.[20] The Ustaše, a fringe movement in pre-war Croatia,[21] attempted to garner support among ordinary Croats and Bosnian Muslims,[22] but never attracted significant support among the populace.[23] The ceding of territory to Italy was a particular blow to their popularity.[24] Special status was given to the German minority, whose members served in the NDH military forces (Einsatzstaffel), and were organized as an autonomous body.[25] From 1942, German minority members were enlisted in the SS Prinz Eugen division.[26]

Following the occupation and division of Yugoslavia, German and other occupation forces introduced anti-semitic laws in accordance with the Nazi Final Solution plan.[27] In the NDH, the Ustaše enacted their own Race Laws,[28] and embarked on a campaign of genocide against Serbs, who were Orthodox Christian, as well as the Jewish and Roma populations throughout the country.[28][29] It established a concentration camp system, the largest of which was Jasenovac,[30] where 77,000–100,000 people were murdered, the majority women and children, primarily Serbs, Jews and Roma, but also anti-Fascist Croats and Bosniaks.[31][32] Around 29–31,000 Jews, or 79% of their pre-war population in the NDH, were exterminated during the Holocaust, mostly by the Ustaše.[33] The Ustaše also murdered nearly the entire Roma population of around 25,000.[34]

The number of Serbs killed by the Ustaše is difficult to determine.[35] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that the Ustaše killed between 320,000 and 340,000 Serbs.[36] Croatian demographer Vladimir Žerjavić calculated the population losses of Yugoslavia, and estimated the total number of Serb civilian and combatant deaths in the NDH at 322,000. Of the civilian casualties, he estimated that the Ustaše killed 78,000 Serb civilians, in direct terror and in concentration camps, and the rest died at the hands of the German and Italian forces, and of other causes.[11] The Ustaše ethnically cleansed Serbs, killed 154 Orthodox priests, plus 3 bishops,[37] expelled most other Orthodox priests, force-converted 240,000 Serbs to Catholicism by May 1943,[38] slaughtering many Serbs even after conversion.[39] A series of armed Serb revolts against the NDH began in the summer of 1941. Wehrmacht General Edmund Glaise-Horstenau blamed the Ustaše crimes for the uprisings and criticized the government of the NDH.[40] The rebel forces were initially a mixture of Communists and Serb nationalist groups, but rifts and fighting between Partisans and Chetniks soon broke out.[41] Partisans advocated unity among all ethnic groups, and opposed Chetnik killing and ethnic cleansing of Muslims and Croats.[42] In early 1942, NDH Chetniks killed many Partisan commanders in Bosnia, and signed alliances with the Ustaše, to jointly fight the Partisans.[43]

Germany, Italy, and Hungary carved up Slovenia, and set out to entirely wipe out Slovenes as an ethnic group, through mass expulsions and forced assimilation,[44][45] which the Slovenian historian Božo Repe describes as ethnocide.[46] Nazi Germany planned to expel 260,000 (a third of) Slovenes from areas they occupied, but expelled around 80,000.[47] The bishop of Ljubljana and leading Slovene politicians welcomed Mussolini's annexation of Ljubljana Province,[48] while conversely, Axis oppression soon led to armed resistance.[49] The Communist-led resistance began in July 1941.[50] Axis authorities sponsored local collaborationist, anti-communist units, which drew most of their members and were supported by the Catholic Slovene People's Party. In 1943, these units were united into the Slovene Home Guard, under the command of SS General Erwin Rösener, who reported directly to Himmler.[51] The Home Guard took an oath to fight with the SS, under the leadership of the Führer, against the Communist guerrillas and their Soviet and Western Allies.[52] Italy set up concentration camps in occupied territory, the largest of which was the Rab concentration camp. An estimated 40,000 Slovenes went through those camps, of whom 7,000 died.[53] During the course of the war in Slovene Lands, mutual terror was practiced by both the Communist-led units and the collaborating forces.[54] In total, around 83–84,000 people lost their lives by the formal end of the war in the Slovene lands, the vast majority killed by the occupation forces. Around 13,200 military and civilian deaths were the result of an inter-Slovene conflict, with collaborators responsible for around 6,000 and Partisans 6,700. Among nearly 30,000 Slovene civilians killed, Partisans were responsible for 4,233 civilian deaths, while the Slovene anti-Partisan, in independent actions or in collaboration with Axis forces, caused the deaths of 1,236 civilians. The latter number does not include civilians that Slovene collaborators turned over to the Axis and were killed or died in Axis concentration camps.[55] (e.g. Slovene collaborators put together lists of Slovene political prisoners and assisted in their deportation to Nazi concentration camps).[56]

Serbia was invaded and partitioned by Germany, Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria, and the NDH. Rump Serbian territory was placed under German military administration, with the help of a civil puppet government led by Milan Nedić.[57] In response to a large, Communist-led uprising in Serbia, the German military in just two months executed 30,000 Serb civilians and Jews.[58] Remnants of the Royal Yugoslav Army organized the Serbian monarchist Chetniks were the first resistance movement. The Chetniks were led by Draža Mihailović and were recognized by the Yugoslav government-in-exile.[59] While it was anti-Axis in its long-term goals and engaged in marginal resistance activities for limited periods, the Chetniks also engaged in collaboration with the occupying forces for almost all of the war.[60] The Chetniks were partners in the terror and counter-terror that occurred in Yugoslavia during WWII. The terror tactics against the communist Partisans and their supporters was ideologically driven.[61] The Chetniks sought the creation of a Greater Serbia by cleansing non-Serbs, mainly Muslims and Croats, from territories that would be incorporated into their post-war state,[62] and carried out genocide against Muslims and Croats during this period.[63] [64][65] An estimated 18,000–32,000 Croats and 29,000–33,000 Muslims were killed by the Chetniks.[66]

The Communist Party of Yugoslavia (KPJ) remained largely inactive while the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact between Germany and the Soviet Union was in effect.[67] During this period, the Soviet Union pursued friendly relations with Germany and considered recognizing the NDH.[68] Following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, Communist-led Yugoslav Partisans issued a call for an uprising.[67] Josip Broz Tito was the supreme commander of the Partisan forces.[69] The Communist leadership saw the war as an opportunity for a revolution and an establishment of a Soviet-style totalitarian regime.[70] Until the 1st half of 1942, during a period described as "red terror", their units were engaged in the mass killing of perceived class enemies, a policy that threatened their popular support. The leadership then changed this approach and focused less on class warfare, until the postwar period.[71]

The Chetniks and the Partisans, the two main guerrilla resistance units, initially cooperated against the Axis, but their cooperation soon fell apart, and they turned against each other. Due to the Chetniks' collaboration with the Axis, Allied support shifted to the Partisan side.[72][73] In 1943, the Allies officially recognized the Partisans as an Allied fighting force.[74] Winston Churchill highlighted the strength and importance of the Partisans and advised the Yugoslav government to reach an agreement with Tito,[75] whose forces generated an appeal among all ethnic groups.[76]

End of the war

editThe arrival of Soviet ground troops in the Belgrade Offensive and Allied logistical support enabled the Partisans to increase their offensive actions. By the end of 1944, with the help of the Red Army, they established control in Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro and Dalmatia.[77] German forces retreated from Serbia, together with Nedić's forces.[78] The Wehrmacht and the HOS established a front in Syrmia to secure the retreat of the German Army Group E from the Balkans.[79] The Partisans conducted mass killings of POWs and ethnic Germans after securing control of Serbia.[80] The Communist leadership adopted a political decision on the expulsion of the German national minority, whom they held collectively responsible for Nazi crimes, and the confiscation of their property.[81] Germany attempted to evacuate the entire German population from Yugoslavia to the Reich, but in late 1944 there were still around 150,000 Germans in Partisan-controlled Vojvodina. By May 1945, most were interned in over 40 concentration camps in the region, in which around 46,000 died.[82]

In May 1944, Tito founded an intelligence service known as the Department for People's Protection (OZNA), modeled after the Soviet NKVD. It represented a military intelligence service and a political secret police of the Communist Party.[83] In August 1944, he founded an army unit called the People's Defence Corps of Yugoslavia (Korpus narodne odbrane Jugoslavije, KNOJ), whose explicit assignment was to "liquidate Chetnik, Ustaša, White Guard and other anti-people gangs".[84]

With the growth of the Partisans, who provided Croats an alternative that appeared more in Croatia's national interest, and the general dissatisfaction with the Ustaše and Nazi German authorities, the NDH had serious difficulties in mobilizing new troops.[85] When in August 1944, a coup d'état against Ante Pavelić, known as the Lorković–Vokić plot, failed, its conspirators were arrested or executed. The main plotters wanted to align NDH with the Allies. The outcome of the plot caused further demoralization. As the war progressed, the desertion rate in the NDH armed force increased,[86] especially among the Croatian Home Guard, the regular army.[87] The Chetniks showed similar signs of desertion.[73]

On 30 August 1944, Tito offered amnesty to Croatian Home Guards, Slovene Home Guards, and Chetniks if they chose to defect to the Partisan side by 15 September. After 15 September, all who had not defected were to be brought to "people's courts". Similar calls were repeated several times after the deadline. In some cases, Croatian Home Guards were killed despite defecting to the Partisans.[88] On the day when the amnesty expired, Tito instructed his subordinates to continue accepting late defectors.[89] A day earlier, King Peter II issued a call to the Chetniks to put themselves under the command of the Partisans. Large-scale defections of Chetniks to the Partisans followed.[90]

The Armed Forces of the Independent State of Croatia (HOS) were reorganized in November 1944 to combine the units of the Ustaše and Croatian Home Guard.[91] Throughout the war, the treatment of Croatian Home Guard prisoners was relatively benign – Partisans would ridicule the captured domobran soldiers and send them home if they did not want to join the uprising. But, on 13 January 1945, Pavelić ordered the domobrani to merge with the Ustaša military, creating a force estimated at 280,000.[92]

Some Chetniks, such as those of Momčilo Đujić's Dinara Division, continued collaborating with the Axis.[93] Đujić's forces fought alongside the Germans and HOS in late 1944 in the battle of Knin against the Partisan 8th Dalmatian Corps. The battle ended in Partisan victory, and the Dinara Division began withdrawing to Slovenia.[94] Pavelić issued an order to provide safe passage to Đujić's troops,[95] and gave them directions of movement. As the path led to Partisan-held territory, and Đujić did not trust Pavelić due to earlier examples of the Ustaše killing Chetniks passing through the NDH, he took an alternate route in agreement with the local Wehrmacht commanders.[96]

After the surrender of Italy in 1943, the Germans sought to reestablish a Slovenian anti-Partisan collaborationist militia, on the basis of a previously Italian backed unit. It was hoped such a force would help the German occupation combat the growing Partisan resistance movement in Ljubljana Province. This led to the founding of the Slovene Home Guard, staffed largely by supporters of an assortment of anti-Communist Slovene political movements, particularly the Slovene People's Party. While they eventually hoped to win the support of the Allies, these anti-Communists were more concerned by the threat of a post-war Communist government in Yugoslavia.[97] Their collaboration with the German occupiers made any future compromise with the Allies untenable, which would have significant repercussions when Slovene Home Guard fighters tried to surrender to the British in May 1945.

In September 1944, at the urging of Western Allies, Slovene members of the Yugoslav government-in-exile in London, called on the Slovene Home Guard to transfer its allegiance to the Partisans.[98] Despite this and Partisan amnesty offers, most Home Guards continued fighting on the German side.[99] In March 1945, Slovene collaborationist leaders, Leon Rupnik and Bishop Rožman, proposed a military-political alliance to the Ustaše leader Ante Pavelić and the Chetniks, to continue fighting the Partisans.[100]

By 1945, the Yugoslav Partisans were known as the Yugoslav People's Army, and numbered more than 800,000 men organized into five field armies. They pursued the remnant of the defeated German and NDH forces.[101][102]

In March 1945, the 4th Yugoslav Army advanced through Lika, Croatian Littoral and Kvarner Gulf. Most of Bosnia and Herzegovina was in Partisan hands by the end of April. On 12 April, the Syrmian Front was broken and the 1st and 3rd Armies advanced west through Slavonia. Only the northwestern part of NDH, with Zagreb as its center, remained under control of NDH authorities.[103] Numerous refugees had gathered there from other parts of NDH. The Partisans carried out reprisals against captured soldiers of the HOS, as well as thousands of suspected civilian political opponents.[104]

Axis retreat

editThe collapse of the Syrmian front in April 1945 accelerated the withdrawal of German forces, which had been retreating from the Balkans since October 1944.[79] Like other Axis troops, forces of the NDH did not want to surrender to the Red Army or the Yugoslav Partisans. They retreated through Slovenia trying to reach the Yugoslav-Austrian border, in order to surrender to the British forces advancing north from Italy.[105] A large-scale exodus of people was planned and organized by the authorities of the NDH although there was no strategic benefit to it: there was no viable destination for all the population.[106] The NDH government's decision to organize a retreat was reached on 3 May.[107] On the same day, the Slovene National Council, established by anti-Partisan forces in October 1944, convened a parliament in Ljubljana and proclaimed a Slovene state within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Slovene Home Guard and other anti-communist forces were joined into the Slovene National Army, as part of Mihailović's Chetniks. The parliament called on Partisans and all Slovenes to cease hostilities, and appealed to the Western Allies for aid. The parliament ordered a retreat to Austria, where they hoped to be accepted by the British as prisoners or as allies in the fight against the Soviets and the Partisans.[108]

Some in the NDH and Slovene political and military leadership believed that the Western Allies would use them as anti-Communist forces and support them in returning to Yugoslavia and regaining power. Slovenian Bishop Gregorij Rožman appealed to the Allies to occupy Slovenia and prevent the Communists from taking power.[105] The NDH leadership abolished racial laws and sent a request for collaboration with the Allies on 6 May,[109] but all of these efforts failed.[105] While the NDH leadership may have organized a civilian retreat to bolster their claims that the Yugoslav Communists were after innocent civilian victims, the sheer number of civilians slowed down the retreat, and made surrender to the Allies unfeasible. Some observers believed the government was using the civilians as a human shield against the Ustaše.[106] The majority of the civilian refugees reportedly held anti-Communist views or feared reprisals.[110]

Divisions of three Yugoslav armies were pursuing the Axis forces.[79] Some units of the Yugoslav 4th Army managed to reach Carinthia before or at the same time as the retreating columns. Additional divisions of the 3rd and 4th Armies were sent to the area in order to capture southern Carinthia and prevent the Axis retreat. The 1st and 2nd Armies were halted near Celje, while the 3rd Army advanced further in pursuit of the retreating columns.[111]

On 6 May 1945, the government of the NDH fled Zagreb and reached a site near Klagenfurt, Austria on 7 May.[112] Pavelić and the military leadership left Zaprešić on the evening of 7 May, intending to join the rest of the NDH regime in Austria.[113] The bulk of the NDH leadership, including Pavelić, escaped in early May, fleeing to Western Europe and Latin America. Partisans captured only a small number of senior military NDH officers.[114]

Zagreb was defended by parts of the 1st Division of the Army of NDH and the 41st and 181st German Divisions, deployed along the unfinished fortified "Zvonimir line" between Sveti Ivan Žabno and Ivanić-Grad. The fierce battle with the Yugoslav 1st Army lasted from 5–8 May. The single bloodiest day in the 1,240-day long history of the 1st Proletarian Brigade was 7 May, with 158 killed and 358 wounded in the fighting for Vrbovec.[115]

Besides the HOS, Slovene Home Guard and the German Army Group E, other military units were retreating.[116] The remnants of the Serbian State Guard, two regiments of the Serbian Volunteer Corps, and a group of Chetniks surrendered to the British near the Italian-Yugoslav border on 5 May. These units were not repatriated to Yugoslavia.[117] The Montenegrin National Army, formed in April 1945 by Sekula Drljević with the support of the NDH government, to gather Montenegrins from NDH in the unit, were retreating together with Croatian forces.[118] Thousands of Russian Cossacks of the XVth SS Cossack Cavalry Corps, stationed in Yugoslavia since 1943, were also retreating to Austria.[119]

On 7 May 1945, Germany surrendered unconditionally to the Allied powers, marking the practical end of World War II in Europe.[107] The German Instrument of Surrender applied to German Wehrmacht forces in Yugoslavia, as well as to other armed forces under German control, such as the Croatian Armed Forces. Ordinarily this would have meant that they, too, had to cease their activities on 8 May and stay where they found themselves. The military of NDH, however, came under the command of Pavelić.[120] As the Germans were about to surrender, General Alexander Löhr, Commander-in-Chief of Army Group E, handed command of the Croatian forces to Pavelić on 8 May.[114] Pavelić issued an order from Rogaška Slatina for his troops not to surrender to the Partisans, but to escape to Austria, to implement the NDH government's decision of 3 May to flee to Austria.[114] Following the capitulation of Germany, Tito issued an address via Radio Belgrade on 9 May calling upon all armed collaborators to surrender, threatening "merciless response" from the people and the army should they refuse to do so.[121]

Most of the German and HOS troops had withdrawn from Zagreb by 8 May, when units of the Partisan 1st and 2nd Armies took control of it. There were relatively few skirmishes and casualties in the city. The 1st Army reported to the General Staff that 10,901 enemy soldiers had been killed and 15,892 captured in taking Zagreb, without specifying battles in which these casualties occurred.[119] That same day, the headquarters of the 51st Vojvodina Division of the Yugoslav 3rd Army issued a dispatch ordering its units to consider all enemy forces who continued resistance after midnight that day, and who were not part of units who had an organized surrender, as persons who did not have the status of prisoners of war, and to treat them as "bandits". The German surrender obstructed the progress of the columns fleeing Croatia northward. By 9 May, Partisan forces had moved into Maribor, which eliminated that escape route. They also took control of Celje on 10 May, but with a force insufficient to halt the columns that were escaping towards Dravograd.[121]

Escape route to Klagenfurt-Viktring

editThe Slovene Home Guard and Slovene civilians primarily used the route across the Loibl Pass.[105] Around 30,000 soldiers, including 10,000 to 12,000 Slovene Home Guards, 10,000 Germans, 4,000 Serbs, 4,000 members of the Russian Corps, and 6,000 Slovene civilians, were withdrawing to Austria.[122] The road to Loibl (Ljubelj) was congested with loaded cars, trucks, wagons, and horse carts. Battles with the Partisans also slowed the retreat.[111]

After passing the Loibl Pass, the columns were headed to the Drava Bridge at Hollenburg. The British were located north of the bridge. The bridge was guarded by German soldiers and was attacked by the Partisans on 7 May. Partisan reinforcements arrived on the following day and set a barrier between Ferlach and Hollenburg, while units of the 4th Motorized Division and the 26th Division of the 4th Army were approaching Ferlach from the west. The Axis troops and civilians were surrounded and tried to fight their way through the blockades. Some German troops surrendered to the Partisans in the Rosental Valley, in accordance with the German instrument of surrender.[123]

On 10 May, the main breakthrough attempt took place. The assault was carried out by the Slovene Home Guard, led by Major Vuk Rupnik, and the 7th SS Division "Prinz Eugen" and SS police units.[124] A radio contact was established with the British, who were ready to accept them if they crossed the Drava. The British refrained from engaging the Axis units fighting the Partisans.[125] On 11 May, the Slovene Home Guard and SS troops launched an infantry attack on the town of Ferlach and took control of it on the evening. The Partisans reported 180 casualties.[126] The remaining Partisan units in the vicinity were repelled, and the column of troops and refugees began crossing the Drava River. They were taken by the British to the Viktring camp near Klagenfurt. By 14 May, all units of the Slovene Home Guard surrendered to the British.[125]

Escape route to Bleiburg

editCroat troops and civilians mostly used escape routes toward Mežica and Bleiburg, and across the Kamnik Alps toward the Jaun Valley in Austria.[105] The main Croatian column moved through the towns of Zidani Most, Celje, Šoštanj, and Slovenj Gradec. On 11 May, the vanguard of the column reached Dravograd. The bridges across the Drava River were barricaded by Bulgarian units that had reached the area on 9 May.[127]

On 11–12 May, generals Vjekoslav Servatzy and Vladimir Metikoš entered discussions with Bulgarian generals to allow the Croatian column to pass into Austria.[128] The discussions were inconclusive, but the Bulgarians suggested they head in the direction of Prevalje and Bleiburg, which the column did.[129] Bleiburg was located some four kilometres northwest of the border of Austria and Yugoslavia. Parts of the columns that had weak or no protection were attacked by the Partisans - on 12 May, Politika carried Yugoslav Army reports of 15,700 prisoners of war in Maribor, Zidani Most, Bled, Jesenice and elsewhere. On 13 May, they reported over 40,000 prisoners taken near Rogaška Slatina, Celje, Velenje, Šoštanj, Dravograd, and elsewhere.[130]

The main column was encircled in the Dravograd pocket. The Croatian Armed Forces had artillery positions in a five kilometers linear distance from Dravograd to the south and used howitzers to fire on positions of the Yugoslav Army. On the night of 13 May, the elite HOS infantry units, commanded by General Rafael Boban, managed to break through the Partisan blockade and the column moved west through Ravne na Koroškem and Poljana towards Bleiburg.[131][132] A large number of Croat soldiers and civilians reached the field at Bleiburg on 14 May.[133] The headquarters of the British 38th (Irish) Brigade were set up in Bleiburg,[134] having occupied the town on 12 May,[133] while the rest of the V Corps was stationed in Klagenfurt.[134]

Surrender at Bleiburg

editThe main group of HOS troops and Croat civilians reached the Bleiburg field on 15 May. They were the head of the 45-65 kilometres-long columns, numbering around 25,000 to 30,000 people.[135][116] The group included various branches of the NDH army, including the Air Force, HOS, and civilian refugees. Most of them camped near the local railroad embankment. The Montenegrin National Army was placed east of the embankment.[136] Around 175,000 people were still on Yugoslav territory and moving towards Bleiburg.[135] Negotiations between representatives of the HOS, the Yugoslav Army and the British were held on the same day in the Bleiburg Castle.[137] The British negotiator was Brigadier Thomas Scott of the 38th (Irish) Brigade.[138] Ustaša infantry general Ivo Herenčić of the V Ustaša Corps, and a translator, Colonel Danijel Crljen, were involved in the surrender negotiations.[139][140]

In the afternoon of the same day, the Croatian forces started raising white flags in surrender.[141] The Partisan representatives included Major-General Milan Basta, the political commissar of the 51st Vojvodina Division, and Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Kovačič Efenka of the 14th Attack Division.[129][139] NDH military representatives attempted to negotiate a surrender to the British, but were directed to surrender to the Yugoslav military.[139] The Independent State of Croatia had joined the Geneva Convention on 20 January 1943, and was recognised by it as a "belligerent".[142]

The Partisan forces of the 51st Vojvodina Division of the Yugoslav 3rd Army and the 14th Slovenian Division had established tactical control over the field of Bleiburg.[134] Milan Basta set an ultimatum to the NDH negotiators - unconditional surrender within one hour, or else they would attack them and not uphold the norms of the international conventions of the Red Cross.[139][143] Basta's ultimatum was extended for another fifteen minutes, after which point a general surrender started.[139] Basta gave Scott assurances that the prisoners would be treated humanely and that only "political criminals" would be tried by courts.[144]

The exact events after the expiry of the ultimatum are the source of the original controversy regarding the repatriations. Teodor Pavić, described as a NDH "courier", wrote that the Partisan forces began strafing the crowd in the Bleiburg field with machine guns and shooting them individually.[143] Petar Brajović, a Yugoslav officer, described a fifteen- to twenty-minute machine gun and mortar fire on the column.[145] Strle wrote that the 3rd Battalion of the 11th "Zidanšek" Brigade and the 3rd Battalion of the 1st "Tomšič" Brigade were involved in the fire, and their records noted at least 16 deaths, mainly from the machine gun fire.[145] A Croatian soldier who survived, Zvonimir Zorić, wrote of a massacre at Bleiburg.[145]

The notion of a massacre at the Bleiburg field was promoted by the remnants of the Ustaša in exile.[146] Croatian-American historian Jozo Tomasevich notes that it would have been physically impossible to assemble all the Croatian refugees in Bleiburg itself, so German and Croatian troops who are said to have surrendered "in Bleiburg" must have done so in various localities, including Bleiburg, and certainly not all in Bleiburg itself. He considers it impossible to establish the exact number of troops and civilians who tried to flee to Austria and were forced to surrender to the Partisans, and stresses that the number of victims has been inflated by pro-Ustaša sources for propaganda purposes, while communist sources have been diminishing it for similar reasons.[97] Croatian historian Martina Grahek Ravančić[147] wrote that the complete extent of the casualties sustained by the NDH column at Bleiburg on the day of the surrender was not described in any available sources. She described a short Yugoslav Army attack on the column as a certainty, likewise that there were casualties, but the number is unknown.[148]

Strle and Milan Basta claimed that as Ustaša forces tried to make a breakthrough at the north side of the valley, three British tanks moved to stop them, reportedly resulting in several casualties. However, only three Croatians provided testimony which supported the notion that there were British tanks in the proximity of the column, but with no mention of such an incident.[145] Tomasevich writes that these kinds of unconfirmed reports of British military involvement, coupled with the legitimate acts of repatriation, were subsequently exaggerated by Ustaša supporters, particularly in the Croatian diaspora. They published biased works that falsely accused the British of "turning a blind eye" to the actions of the Partisans.[146]

Later the same day, NDH generals Slavko Štancer, Vjekoslav Servatzy, and Vladimir Metikoš oversaw the surrender to the Partisans.[148] British army reports say Štancer had previously been captured by the Partisans when they strayed from the column, seeking the British.[139] The surrender continued for several days and at various locations; it took until 21 May for Tito to order the Partisans to withdraw from Carinthia.[149]

Other Carinthian repatriations

editSeveral other repatriations took place elsewhere in Carinthia during May 1945. Yugoslav intelligence officer Simo Dubajić negotiated with British forces about the organization of surrender and repatriation elsewhere along the Yugoslav-Austrian border.[150] The extradition of Croat internees of the Viktring and Krumpendorf prisoner-of-war camps, located north of the Drava River, began on 18 May. The prisoners were assured that they were being transported to Italy. The repatriation took place in the village of Rosenbach and the town of Eberndorf. The transports continued on 19 May when Rosenbach and Lavamünd, northeast of Bleiburg, were used as extradition places, while some were transported to Bleiburg. Internees of the Grafenstein camp were also transported. Thousands more were handed over in the following days, mostly in Rosenbach and the Bleiburg railway station. The last transport was on 23 May when 800 Croat prisoners from Grafenstein were taken by rail to Bleiburg. British war diary records note that the extraditions of Croats ended on 24 May.[151]

The transports of Serbs and Montenegrins followed on 24 May, with three regiments of the Serbian Volunteer Corps. The first repatriation of larger groups of Slovene prisoners took place on 27 May, together with the remaining Serbs and Montenegrins. The repatriation of Slovenes also took place in Rosenbach or Bleiburg, except for the severely wounded that were accommodated in a hospital in Klagenfurt.[152] The Slovenes were also told by the British that they will be transported to camps in Italy.[135] The last Slovene group was handed over on 31 May. The following day, 2,700 Slovene civilians were scheduled to be transported to the border, but the transport was stopped by the British due to reports of massacres in Yugoslavia. All repatriations were canceled and a decision was made that only those who wanted to return to Yugoslavia would be transported.[153] According to an estimate of the British V Corps, a total of 26,339 people were extradited from the camps by 30 May, including 12,196 Croats, 8,263 Slovenes, 5,480 Serbs, and 400 Montenegrins.[152][154]

On the evening of 20 May, a group of NDH troops appeared near Ferlach, located approximately 40 km (25 mi) west of Bleiburg, and attempted to set terms for their passage west. "As the Ustaše did not want to surrender" reads the operational diary of the 2nd Battalion of the Partisan 11th Dalmatian Assault Brigade, "we attacked them at 21:00 hrs. On this occasion we took 24 Ustaše soldiers and one officer".[155] British forces repatriated around 40,000 Cossacks to the Soviet Union's SMERSH, near Graz.[156] The repatriation of Cossacks to the Soviet Union from camps near Lienz began on 28 May.[157]

Allied stance

editAt the Yalta Conference on 11 February 1945, an agreement was reached on the repatriation of citizens from the signatory states, the US, the UK, and the USSR, to their country of origin. As Yugoslavia was not a signatory, the repatriation of Yugoslav citizens was not mentioned in the agreement. At the time of the Axis retreat from occupied Yugoslavia, the British V Corps of the Eighth Army was stationed in southern Austria, which was within the area of authority of Field Marshal Harold Alexander.[158] The Yugoslav Army reached southern Carinthia in early May and declared it a part of Yugoslavia. This caused strained relations with the British, who supported an independent Austria in prewar borders.[158][159] Due to Yugoslav refusal to withdraw from Austrian Carinthia, as well as from the Italian city of Trieste, the possibility of an armed conflict between the British forces and the Partisans emerged.[160]

The Western Allies did not expect the movement of a large number of people in the V Corps area.[161] The retreat of larger groups of "anti-Tito forces" was reported by Ralph Stevenson, the British ambassador in Belgrade, on 27 April.[162] There was no consensus among British authorities on how to deal with them. Stevenson recommended their internment in camps rather than repatriation.[160] British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed with Stevenson's suggestion as "the only possible solution".[163] The 8th Army issued an order on 3 May that Axis forces from Yugoslavia "will be regarded as surrendered personnel and will be treated accordingly. The ultimate disposal of these personnel will be decided on Government levels".[164] Until 14 May, the British accepted the surrender of thousands of retreating troops and civilians.[165]

A report to the V Corps from 13 May noted the movement of hundreds of thousands of people towards Austria. On the following day, the V Corps estimated that once the columns arrived, the food situation would become critical, and cited an insufficient number of guards to manage the people.[166] Harold Macmillan, the British Minister Resident in the Mediterranean, recommended the immediate transfer of Cossacks to the Soviet Union. Regarding the column that was approaching Bleiburg, the brigade stationed in the town was instructed to "keep it south of the Drava".[167] Brian Robertson, Alexander's Chief Administrative Officer, issued an order to the 8th British Army on 14 May to hand over all surrendered Axis personnel of Yugoslav nationality to the Yugoslav Army.[168] The order excluded Chetniks, who were to be transferred to Italy. The repatriations were opposed by Alexander Kirk, American political advisor to the Supreme Headquarters (SHAEF), who asked the US State Department for advice. Joseph Grew, the US Under Secretary of State, agreed with Kirk and instructed him to inform the Allied Force Headquarters (AFHQ) of "violation of the agreed Anglo-American policy".[169]

The AFHQ contacted the Yugoslav authorities on 15 May regarding the repatriation of "Yugoslavs".[160] In line with the orders received by 15 May, the V Corps rejected the surrender of the column at Bleiburg. At the same time, the V Corps entered negotiations with Yugoslav representatives regarding the repatriation of other POWs and the withdrawal of the Yugoslav Army from Carinthia. An agreement was reached for the Yugoslav withdrawal on 21 May.[170] The repatriations began earlier, on 18 May.[171]

A November 1945 report from the British Foreign Office noted that it had not yet been decided on a high level whether the prisoners should be transferred to Yugoslavia.[172] Local British commanders were given imprecise and contradictory orders. On 17 May, Brigadier Toby Low, Chief of Staff of the V Corps, ordered that "all Yugoslav nationals at present in Corps area will be handed over to Tito forces as soon as possible. These forces will be disarmed immediately but will NOT be told of their destination".[173] Several hours later, an order arrived from Alexander to evacuate all Yugoslav prisoners to northern Italy.[173] On the same day, Alexander sent a telegram to the Combined Chiefs of Staff, in which he wrote that to return the prisoners to their country of origin "might be fatal to their health".[174]

Instructions and provisions made by the Allies in the following days frequently conflicted.[175] Two conflicting instructions from the AFHQ arrived on 23 May: the first was to return the Yugoslav citizens from the 8th Army area to Yugoslavia unless it involved the use of force. The second instruction was that Yugoslav citizens should not be returned to Yugoslavia against their will, and that they should be "moved to suitable concentration area and screened".[176] The confusion in the line of command led to a series of meetings between the AFHQ representatives and the 8th Army. The conclusion of the meetings on 27 May was an implicit support to the policy of not telling the prisoners their destination, the non-use of force, and that "it was unwise to make any further interpretation".[177][178] The repatriations continued until 31 May, when they were canceled following the appeal of the head of the Viktring camp and the local British Red Cross.[179] The repatriations were the topic of much subsequent debate.[180][181][182][page needed]

March back

editRepresentatives of the HOS of NDH accepted the surrender on 15 May at 16:00 hours. After the immediate repatriation of the soldiers at Bleiburg was complete, the Yugoslav forces began disarming them and started preparations for transporting the prisoners back.[184] A large number of columns of prisoners were formed in rows of four that were sent on a forced march through Slovenia. Due to the presence of the British Army, the initial treatment of prisoners was correct.[185] However, it got worse as the columns moved away from the border. The prisoners were given no food or water and were looted of valuables. Those who lagged behind were shot.[186] Individual killings and executions of smaller groups of men soon began. The columns were in Dravograd directed to Maribor or Slovenj Gradec and Celje.[187] On 17 May, the British started the repatriation of Croat internees of the Viktring camp, mostly members of the HOS.[188]

The columns marching towards Maribor, where transit camps were set, were moving along the Drava River.[186] During the march, bodies could be seen floating in the Drava and on the banks of the river.[189] The first prisoners arrived in Maribor on 17 May and were placed in transit camps. Other larger columns arrived in the following two days. At the camps, prisoners were sorted based on their unit and year of enlistment.[190] A part of the prisoners were sent on further marches or transported with trains to Celje and Zagreb. The rest were brought by trucks to anti-tank trenches in Tezno near Maribor, with their hands tied with wire, where they were lined up and killed. The killings lasted for several days until the trenches were filled with dead bodies.[186] A total of 1,179 bodies were recovered, with estimates that 15,000 people may have been killed in the Tezno massacre,[1][191][192] largely members of the HOS. Among them were also some members of the Montenegrin National Army and POWs of other units.[193]

Prisoners directed from Bleiburg to the town of Slovenj Gradec were joined by a large number of refugees that were stuck on the Dravograd-Slovenj Gradec road. Several transit camps were set in the town where prisoners were placed and sorted. Around 1,500 were killed in the nearby village of Žančani. The prisoners were only briefly held in Slovenj Gradec, mostly a day, before they continued their way to Celje. Anyone who stepped out of the column to take a rest or drink water was shot. Those that were too exhausted to continue the march were also shot. In Celje, most of the prisoners were placed in a football yard on the outskirts of the city. The command of the 11th Krajina Division of the 1st Army reported on 17 May that they received 30,000 prisoners. Anti-tank trenches near the Sava River and in the area of Bukovžlak were used for executions.[194] Prisoners were killed in various ways; on one occasion around 100-200 were locked in an enclosed water reservoir. Water was then slowly released until all of them drowned.[195][196]

A column of 40,000 people, consisting primarily of Croat soldiers, moved from Celje to Zidani Most on 18 May. A part of the captives were separated there, and led to the nearby forests and killed.[197] The column reached Samobor on 20 May.[198] They were not given food during the trip, but locals left them food and water by the road. Prisoners were placed in several smaller camps and prisons in the town, where selections were made again. Most of the prisoners were from Samobor sent to Zagreb and led through the city by foot. Trains with prisoners from other locations, mostly from Maribor, were also coming to Zagreb. The city's transit camps were not suitable for the accommodation of a large number of people, so many prisoners were placed in yards. The camps were surrounded with wire fences, behind which citizens gathered, bringing food or seeking relatives and friends.[199] One of the largest camps in the area was in Prečko. Prisoners were given food there, albeit not regularly. Around 50 died of hunger and illness.[200] Aleksandar Ranković, the chief of the intelligence service, was dissatisfied with the pace of executions in Zagreb and sent a letter to the Croatian branch of the OZNA, demanding greater resoluteness.[201] An increased number of arrests of Zagreb's citizens followed during June and July 1945.[198]

The repatriation of Slovene and Serb internees from Viktring began on 24 May.[202] The transports of around 11,000 Slovene Home Guards and 600 Slovene civilians were done in two directions: from Rosenbach in Austria to Jesenice, who were then imprisoned in internment camps in Kranj, Škofja Loka or Šentvid, and from Bleiburg to Celje, where the Teharje camp was located. The prisoners were beaten and many were killed on the way. The transport and liquidations were carried out by the Corps of People's Defence of Yugoslavia (KNOJ) and the Department for People's Protection (OZNA).[203] Internees of the Šentvid camp were taken to the Kočevje region, where thousands were killed and disposed of in caves, pits and ravines in the Kočevski Rog massacre. Internees of the Teharje camp were killed in its vicinity and in the surrounding caves and mines, including the Barbara Pit coal mine.[204] Out of 5,000 Slovene Home Guards brought to Teharje, almost all were dead by August 1945.[205] A total of 800 Slovene Home Guards and civilians were executed at Podutik near Ljubljana.[206] The decomposing bodies at the location contaminated Ljubljana's water supply, so a group of German POWs were ordered to relocate the bodies to a new mass grave.[207]

The OZNA reported that the main movement of columns of prisoners from Slovenia and the Austrian border was carried out by 8 June. Most of the columns reached their destination where permanent camps were located, 12 of which were in Croatia and 11 in Vojvodina. According to the report, there were a total of 175,922 prisoners.[208] On 25 June, Deputy Prime Minister of Yugoslavia Edvard Kardelj sent a dispatch to Slovenian Prime Minister Boris Kidrič, requesting him to speed up the liquidations as a general amnesty will soon be passed.[209] The decree "on general amnesty and pardon" for Chetniks, the Serbian State Guard, Croatian and Slovene Home Guard, and Albanian and Muslim militia, was adopted on 3 August.[210] According to a report from February 1946, 41,320 prisoners were granted amnesty based on this decision.[211] All those who had been discharged from camps had to contact their local authorities. Some faced trials and sentences to prison or forced labor. Others were under surveillance of the KNOJ and the secret police. On 2 March 1946, the Supreme Command of the Yugoslav Army ordered the release of "all Yugoslav nationalities - members of enemy military formations, except those against whom criminal proceedings have been initiated."[212] Internment and labor camps continued to operate in the following years.[213] The purges that started at the end of the war continued until the early 1950s.[80]

Coverage and aftermath

editThe events in the aftermath of the war were censored in Yugoslavia. Mass graves were concealed or destroyed, in accordance with an order by the Federal Ministry of Interior Affairs from 18 May 1945.[214] Relatives of the victims faced persecution and were treated as second class groups.[215][verification needed] Until the 1950s, there were strict border controls in Yugoslavia, but tens of thousands of people emigrated illegally.[216]

It was not possible to visit the graves located in Yugoslavia, so Bleiburg in Austria became the main location where political emigrants, survivors, or families of the victims could gather and hold a commemoration.[217] The first commemoration on the fields of Bleiburg was in 1952 on All Saints' Day. Since then, the Bleiburg Honorary Guard (Počasni bleiburški vod), an association founded by former members of the Ustaše,[218] organized an annual commemorative event, together with the Catholic Church in Carinthia. The Yugoslav consulate in Klagenfurt sent diplomatic protests to the Austrian government, but the commemorations were never banned by Austria.[219][220] The commemoration was seen as a provocation by Yugoslavia. Prohibited Croatian symbols were openly displayed and it drew attention to postwar killings which the Yugoslav authorities denied.[221] The Bleiburg events were also used as a tool for historical revisionism and the focus of collective resentment by the remainder of the Ustaše and their supporters. The number of victims was artificially inflated.[222]

The Yugoslav State Security Administration (UDBA) monitored the activities of the participants of the commemorative event and conducted a series of attacks on its organizers. During the ceremony in 1966, a bomb exploded in a country inn in Loibach, but none of the attendants was injured. Nikica Martinović, the chairman of the Bleiburg Honorary Guard, was assassinated by the UDBA in Klagenfurt in 1975. The following year a bomb was found in front of the tavern of Mirko Karačić, also a member of the Bleiburg Honorary Guard. In spite of the threats and attacks, the commemoration continued to be held annually until the breakup of Yugoslavia.[223]

Gatherings and commemorations were also held in other countries. In 1960, on the 15th anniversary commemoration held in Cleveland, the Bleiburg Tragedy Research Committee was founded by Croatian emigrants.[224] In 1961, the commemoration in Cleveland was attended by US Congressman Michael A. Feighan. The Yugoslav consul in Pittsburgh, Ivan Mirošević, protested against it and requested the gathering to be banned. Feighan criticized the consul and Josip Broz Tito during his speech at the commemoration. Mirošević was expelled from the US for his comments.[225] In 1965, commemorating the 20th anniversary, US Senator Frank Lausche condemned the post-war killings in Yugoslavia.[226] Organizations of Croatian emigrants in Germany and USA requested a Red Cross investigation of mass grave sites, which was rejected by Yugoslavia.[227]

In 1976, a marble monument was erected in the Unter-Loibach cemetery and in 1987, a monument was erected on the Bleiburg field with the inscription "In Honor and Glory of the Fallen Croatian Army, May 1945" in Croatian and German language. The monument had the Croatian coat of arms and the Islamic star and crescent engraved.[219]

Investigations of mass graves

editDiscussions about the post-war massacres were forbidden in Yugoslavia, so the investigations of mass grave locations began only in the 1990s, after the fall of communism.[228] In 1992, 1,163 bodies were excavated from 23 mass graves in the forests of Macelj, leaving around 130 possible mass grave locations unexplored.[229] In 2002, the Slovenian government established the Governmental Committee for Settlement of Questions on Secret Mass Graves, with the assignment of "recording of data about the number and locations of mass graves" after the end of World War II.[228]

The Tezno mass graves near Maribor were discovered in 1999 during the construction of a motorway. 1,179 corpses were excavated from a 70 meter long part of the trench. In 2007, the Commission on Concealed Mass Graves in Slovenia, founded in 2005, analyzed the entire Tezno trench and found human remains at a length of 940 metres, estimated to contain the remains of around 15,000 victims.[191] In 2009, the Barbara Pit near Huda Jama in Slovenia was uncovered, and 726 human remains were exhumed by December 2009.[230] The same year, more pits were uncovered on two locations near the Croatian-Slovenian border, one near the village of Harmica and the other near Gornji Hrašćan, estimated to hold, together, around 4,500 bodies.[231]

By mid 2008, 581 concealed grave sites were registered by the Slovenian Commission on Concealed Mass Graves. The number rose to more than 600 grave sites in 2010. The commission estimates that there are around 100,000 victims in those graves in Slovenia alone.[232] Unlike in Slovenia, there was no serious research of mass graves in Croatia by the Croatian government.[233] In 1991, the Croatian Parliament established the Commission for Determination of War and Post-war Victims. The commission began its work in 1994, but was abolished in 2002, with no significant contribution to the research.[234]

Number of victims

editThe exact number of deaths on death marches and in labor camps after the end of the war is difficult to determine.[235] Geiger writes that number of Bleiburg-related casualties, provided in the literature mostly ranges from 50,000 to 200–250,000.[236] Other historians also cite estimates of 20,000 to 40,000, while noting that pro-Ustaše writers inflate Croat casualties,[237][97] and that many estimates are not based on individual victim lists, thus making them unreliable.[238]

Estimates on the number of casualties were first provided in emigrant literature, much ranging from 100,000 to 600,000 deaths, mostly on the basis of eyewitness accounts.[239] Yugoslav dissident Milovan Đilas wrote in 1977 that the figure is higher than 20,000, but did not exceed 30,000.[240] In 1989, the historian Franjo Tuđman, who at the time of Bleiburg was a Croatian representative at the Supreme Headquarters of the Yugoslav Army,[241] and later became Croatia's first president, estimated the number of Bleiburg-related victims at 35,000 to 40,000,[242] and wrote of the "Bleiburg myth", stating that estimates of hundreds of thousands of victims were greatly exaggerated.[243] Tuđman cited Allied reports that by June 1, 1945, a total of 26,399 members of "Yugoslav quisling forces" had been turned over from Bleiburg and other parts of Austria to the new authorities (later a total of 29,792 prisoners), of whom 12,196 were Croats, 5,480 Serbs, 8,263 Slovenes, and 400 Montenegrins.[244] The events were also discussed in November 1945, when Stalin mentioned in a conversation with Polish Communist leader Władysław Gomułka that the Yugoslav partisans had shot 14,000 of some 34,000 of "Pavelic's captives".[245]

Tomasevich writes that for propaganda purposes, Ustaše and pro-Ustaše writers sought to maximize the number of Croat Bleiburg victims, while minimizing Jewish, Serb, Roma and antifascist Croat victims of the Ustaše.[97] He states that many collaborationists perished in the final intense battles, when they refused to surrender, even after the surrender of Germany. He notes that Ustaše sources could not have known the number of forces fleeing, the number that died in final battles, the number captured, etc., and they provide no such detail, not even the units involved. Thus, their Bleiburg victim estimates are subject to wide error.[246] Macdonald also cites the efforts of radical Croat writers to inflate the number of Croat Bleiburg victims to hundreds of thousands, similar to how nationalist Serbs writers inflate the number Jasenovac victims.[237]

In the 1990s, Croatian demographer Vladimir Žerjavić conducted the first systematic research, based on demographic estimates.[247] Thus, Žerjavić wrote that extreme Croatian emigre estimates of 300,000 Croat Bleiburg victims were clearly exaggerated, since his demographic data shows a total of 170,000 Croat WWII victims, on all sides.[248] Žerjavić writes that, unlike for Jasenovac, no victim lists were available for collaborationists at the time. Thus, he guessed 99,000 total Croat and Bosniak NDH armed forces victims, then noted "it is very difficult to evaluate what percentage of them died during the war, but if we estimate 50%, that means [Croat and Bosniak] losses related to Bleiburg could amount to about 50,000."[248] He noted that the great majority of captured civilians were released, thus Bleiburg victims were mainly members of NDH armed forces.[248] Of the estimated 45,000 Croat victims, Žerjavić states 11,600 of those lost their lives in the final battles before surrender, and 33,300 after surrender.[249] In a 1992 work, Žerjavić estimated 57,000 to 65.000 total victims of all nationalities,[12][250] including 45,000 to 55,000 Croats and Bosniaks, 8,000 to 10,000 Slovenes, and 2,000 Serbs and Montenegrins.[236] In 1995, he segmented the Croat-Bosniak losses to 45,000 Croats and 4,000 Bosniaks, and a further 4,000 Croats and 2,000 Bosniaks in "individual cleansings" from 1945 to 1947.[251]

Geiger notes there are researchers who insist victim numbers can only be determined via individual names, and have thus raised serious objections to Žerjavić's statistical estimates, stating these are insufficient and unreliable in determining the number of fatalities.[238] Žerjavić writes that he had data from the 1964 Yugoslav census of individual victims of occupiers and collaborators, thus his estimates of these victims are largely confirmed by individual names.[252] However, he had no victim lists on the collaborationist side,[248] just as he had no individual victim lists for the 1990s war in Bosnia, when he estimated 215,000 total victims, including 30.000 Croats.[253] Later the Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Center built a database of 101,040 individual victims, including 8,403 Croats.[254] These numbers are now widely accepted as the most authoritative,[255] indicating that without individual victim data, which were also lacking for Bleiburg, Žerjavić greatly overestimated Bosnian War victims, with the largest overestimate for Croat victims.

In 1991, the Croatian government created the Commission for Determining Wartime and Postwar Victims of the Republic of Croatia, led by Vice Vukojević, a member of the Bleiburg Honor Guard, who claimed Jews ran the Ustaše Jasenovac death camp.[256] The Commission selectively focused on documenting Croat victims on the NDH side, since they were not registered in previous Yugoslav victim censuses.[257] In 1999, the commission published data listing 13,300 mostly Croats from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, who lost their lives related to Bleiburg.[258] 83% of these were members of NDH armed forces, including 5,503 Ustaše, 3,101 Croatian Home Guards and 2,492 unclassified members of the Croatian Armed Forces. The remaining 2,204 were listed as "other or unidentified". The data for persons "killed outside of combat" is not categorized by year of death.[4] The commission cited that, according to Slovenian estimates, there were around 190,000 victims in the graves in Slovenia alone (Mitja Ferenc, in charge of uncovering postwar graves in Slovenia, later stated that the number of victims is fewer than 100,000, in the tens of thousands)[259][3] The commission was dissolved in 2002, and no further governmental research was conducted.[257]

Ivo Goldstein notes the Croatian Commission's detailed Bleiburg data were never published, neither was promised data on Croat victims from similar projects by the Croatian Historical Institute (HIP), the Catholic Church and others.[260] Thus none can be verified, in contrast to the Jasenovac victim list, published online.[261] While victim lists have been published for some sub-areas, these contain many errors, including listing as Croat WWII victims people who died naturally decades later. The lists also show that nearly all Croat Bleiburg victims were members of armed forces, with no children and only one woman (for aiding postwar Ustaše guerillas), thus contradicting Croatian rightists, who claim civilians, women and children were targeted.[260] This differs from Jasenovac, where the majority of 83,145 named victims are women and children.[222] Goldstein states that in view of 13,300 listed Bleiburg victims (some no doubt killed in battles before surrender), it may be time to revise downward Žerjavić's estimate of 45,000 to 55,000 Croat and Bosniak Bleiburg victims.[261]

The governmental commissions in Slovenia published more thorough data.[233] In 2005, the Slovenian government established the Commission on Concealed Mass Graves in Slovenia. The commission estimates that there are around 100,000 victims of all nationalities in the graves in Slovenia.[232] The Institute of Contemporary History in Ljubljana launched a research project to establish the number of casualties during and after the Second World War in Slovenia. As of 2008, their data shows that 14,274 Slovenians were killed in "post-war violence in Slovenia", which includes non-Bleiburg victims. The number includes 12,431 Slovene Home Guards and 1,076 civilians.[262] According to data published by Slovenian historian Vida Deželak Barič in 2014, there were a total of 14,999 Slovenian victims of post-war killings, including 12,101 Slovene collaborationist POWs, 2,199 civilians, and 547 with an unknown status. This includes victims unrelated to Bleiburg. Deželak Barič listed among the civilian casualties all 529 victims from the German minority, who she notes played a prominent role in Nazi forced Germanization and other repressive acts against Slovenes. [263]

In April 2008, the Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the European Union organized the European Public Hearing on Crimes Committed by Totalitarian Regimes, and the resulting document included various research including that of Mitja Ferenc, noting official data on 3,986 known wartime graves and mass graves in Slovenia from World War II,[165] Milko Mikola, indicating that the victims were executed en masse without a trial,[264] and Jerca Vodušek Starič who wrote about purported mass killings following liberation of Slovenia and Croatia in May 1945: "It is impossible to find out the exact number of those liquidated. Today the number reaches 14,531 Slovenes and an estimate [of] 65,000 to 100,000 Croats. Among them were also civilians."[265] In 2011, Mitja Ferenc, in charge of uncovering post-war graves in Slovenia, stated that "regarding the victims there is only an estimate, I myself think that it is fewer [than 100,000], how many I don't know. Certainly some tens of thousands" and that "from the end of the war to January 1946 about 14,000 Slovenians were murdered. Among them were about 1,100 civilians; the remainder were mostly members of the Slovene Home Guard forces and a smaller number of Chetniks."[3]

Where estimates could later be verified, they showed large overestimates. Thus, after an initial 700 victims were recovered from Barbar Pit (Huda Jama), the President of the Slovene Commission on Concealed Mass Graves, Jože Dežman, claimed that more than 5,000 victims were buried there.[266] In the end a total of 1,416 casualties were recovered.[267] Goldstein notes that Mitja Ferenc similarly overestimated remaining victims at Barbara Pit by a factor of 3 times, and he questions Ferenc's Tezno estimates, since Ferenc used the same methodology to estimate 15,000 victims at Tezno, based on a total of 1,179 recovered corpses.[268]

Grahek Ravančić states that Žerjavić's research is accepted in most related literature.[269] Conversely, Geiger notes that researchers have raised serious objections to Žerjavić's statistical methods, stating that all such estimates which are not based on individual victim lists, are unreliable.[238] Ewa Tabeau also criticized Žerjavić's methodology when he estimated 215,000 Bosnian War victims, compared to later estimates of around 100,000, a figure now widely accepted.[270][255] Jozo Tomasevich used Žerjavić's estimates of 70,000 killed, connected with Bleiburg and Viktring.[12] Croatian historian Slavko Goldstein cited the losses of 50,000 Croats and 20,000 Serbs, Slovenes, and others.[271] Croatian historian Martina Grahek Ravančić considers the total number of victims at around 80,000, since the Slovenian research showed a higher number of Slovene deaths than Žerjavić's research.[272] On the other hand, Goldstein notes that the 1990s Croatian Commission found only 13,300 Croat Bleiburg victims, versus Žerjavić's estimate of 45,000 Croat victims, and states that Žerjavić's Croat victim estimates should be revised downward.[260] Vladimir Geiger, who states that statistical estimates are unreliable, writes that based on such statistical estimates, a minimum of 70,000 to 80,000 people were killed.[236] Swiss historian Michael Portmann compared the estimates, calculations and lists of human losses. His appraisal of the death toll is 80,000, "60,000 under the keyword "Bleiburg" and 20,000 under the keyword "Viktring" and "Kočevje"", from May to August 1945.[273] For Croatian losses, Portmann cites Žerjavić's estimate of 45,000 victims, while for losses among the German minority in Slovenia he claims 2,000 victims in just one camp,{{sfn|Portmann|2004|p=72}} compared to a total of 111 such victims in all Slovene camps, as determined by Slovene researchers.[263]

Croatian historian Ivo Goldstein, in his book Croatia 1918-2008, has posited that contemporary documentation supports the existence of up to 116,000 NDH soldiers and up to 60,000 Croatian civilians in the main columns through Slovenia. In addition, on a separate route there were around 17,000 members of the Slovene Home Guard, the Serbian Volunteer Corps, Chetniks and some smaller NDH army units, together with around 10,000 Slovenian civilians.[274] Croatian historian Zdravko Dizdar analyzed the published victim lists and materials collected by the 1992 Croatian Commission. According to him, the data shows that 62,000 Croat post-war victims are personally identified.[239] Geiger says of Dizdar's numbers that "although statistically possible, these are obviously rough estimates, for [Dizdar] did not indicate which victim lists and publications were consulted, how many fatalities were specified in individual lists and how the verification of data was done".[258] Grahek Ravančić says that more than 5,000 named individuals are listed in known Croatian victim lists related to Bleiburg. She notes that some victim lists are "subjective", and some include all casualties during the war without a specific year and place of death, so "it’s difficult to determine the number of victims from these lists that were killed as part of Bleiburg".[275] A number of authors cite tens of thousands of killed. In Croatian emigrant literature, the prevailing number is 200,000 killed Croats.[276]

Legacy

editFor decades after the killings, the government of Yugoslavia under Josip Broz Tito put forward a sanitized version of the repatriations that glorified the communist cause.[277] Other communist governments and historians echoed these narratives, with only the fall of Communism in Eastern Europe finally bringing a fuller picture of the events.

Commemorations

editWith the transition to democracy in the 1980s and 1990s, the interest in revealing information about the Bleiburg repatriations grew.[278][279] In May 1994, an International Symposium for Investigation of the Bleiburg Tragedy was held in both Zagreb and Bleiburg, where several authors discussed the deaths at Bleiburg and estimated them to be in the tens of thousands. This was later published by Školska knjiga as Od Bleiburga do naših dana.[6]

The Republic of Croatia, by an act of the Croatian Parliament in 1995, started to officially commemorate the victims at Bleiburg,[280] at a time when Franjo Tuđman and the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) were in power. More recently, as commemorative events became less of a political event, the radicals were largely marginalized and the focus of the commemoration turned to the actual victims of the repatriations.[279] Many top-ranking politicians and Catholic and Muslim clerics visit the Bleiburg site annually. Prime Minister Ivica Račan visited the site in 2002.[281] Prime Minister Ivo Sanader visited the site in 2004.[282] For the 60th anniversary commemorations in 2005 a large crowd was in attendance, with speeches by Croatian parliamentary speaker Vladimir Šeks and head of the Muslim Community of Croatia, Mufti Ševko Omerbašić.[283] In 2007, a new altar was installed at the site and was inaugurated by Cardinal Josip Bozanić before some 10,000 people.[284][285]

In 2004, a memorial park was built in Teharje, Slovenia, where an annual ceremony in remembrance of post-World War II victims is held.[286] In 2007, Slovenia's government announced plans to make the Tezno trench a memorial park and cemetery.[287] In 2008, the Croatian and Slovenian governments reached an agreement of cooperation on organizing military cemeteries, similar to earlier agreements which Slovenia reached with Italy and Germany.[288] Croatia's Prime Minister, Zoran Milanović, visited Bleiburg in September 2008. He stated that all victims had the right to a fair trial, [clarification needed] and that his motive was not political.[289]

Controversy

editIn 2009, Croatian President Stjepan Mesić criticized the Parliament's representatives who did not react to people in the crowd displaying Ustaše iconography at the commemoration, which is ostensibly illegal in Croatia, at a state-sponsored event.[290] In 2010, Croatian president Ivo Josipović said he would not attend the year's May Bleiburg commemoration as long as Ustaše iconography was present,[291] although he did make a separate visit to the Bleiburg memorial in June in addition to his visit to the Tezno memorial.[292] In 2012, Croatia's parliament decided to revoke funding for the annual Bleiburg commemoration.[293] The reason given by Milanović was that the government would not fund what had become a politically partisan event concentrating on the NDH, rather than mourning the victims.[294] In 2012, the Croatian leadership laid wreaths only at the monument in Tezno.[295]

As Croatian academician Vjeran Pavlaković, an assistant professor in the Department of Cultural Studies at the University of Rijeka, writes in Deifying the Defeated Commemorating Bleiburg since 1990,

"The blurring of the past and the present is an integral part of the Bleiburg commemorations; not only do the participants dress in Ustasa uniforms, display Ustasa insignia and iconography, and sell paraphernalia associated with the NDH and its leaders, but there is an active discourse about the Croatian War of Independence accompanied by images of heroes (as well as individuals guilty of war crimes) from the conflict in the 1990s."

Pavlaković concludes that

"[T]he effectiveness of Bleiburg to act as a site of memory can be attributed to the fact that it represents both a traumatic past, as well as a moment of rupture, or historical discontinuity. Both of these factors give the commemorations at Bleiburg emotional weight and political significance, especially at a point when Croatia was going through another historical transition in the 1990s. It also meant that the Bleiburg myth was easily manipulated; the victims of the Bleiburg tragedy were actively invoked not only to distort the Ustasa past, but to justify the resurgence of extreme nationalist political options. The Bleiburg myth became one of many historical moments that symbolized Croatian martyrdom, due to the prevailing narrative of victimization by Greater Serbian aggression during the 1990s. The martyrium myth is one of the most common archetypes in the taxonomy of myths... The danger of presenting the victims of Bleiburg exclusively as martyrs for the Croatian state, however, is that the reality of the NDH regime and the crimes it committed are ignored in the new, revised narrative of World War Two.[296]

The 2015 commemoration was the largest on record, with more than 20,000 people attending. In 2016, the Croatian parliament reintroduced sponsorship of the event in order to show reverence for the victims of Communist-totalitarianism after the Second World War.[297]

In 2018, Austrian courts convicted five Croats of performing Nazi salutes or shouting Ustaše slogans at the commemoration. The convicts all received suspended sentences.[298]

On 8 March 2019 the Catholic Church in Carinthia in Austria prohibited priests from performing mass at Bleiburg commemorations. E. Guggenberger, interim administrator of the Diocese of Gurk-Klagenfurt, wrote, "the mass in the field near Bleiburg has become part of a manifestation that is politically instrumentalised and is part of a political-nationalistic ritual that serves a selective experience and interpretation of history." The letter claims the event undermines the Catholic Church's reputation.[299] Three Austrian EU parliamentarians criticized the Bleiburg commemorations as "the largest fascist gathering in Europe",[300] and largely as a result of the display of fascist symbols during Bleiburg commemorations, the Austrian government in 2019 passed a law forbidding the display of Ustashe symbols, along with previously prohibited Nazi, ISIS and other symbols.[301] Austrian courts have sentenced Croatian participants at the Bleiburg commemorations for fascist salutes and displaying fascist symbols.[302] The World Jewish Congress and the Wiesenthal Center joined in condemning the Bleiburg commemoration, with the World Jewish Congress stating the event has been “used to glorify individuals who supported or were actively involved in the activities of a regime which had executed hundreds of thousands of innocent men, women, and children only because of their ethnic or religious identity”.[303][304][305][306]

In 2020, Catholic Mass sponsored by the Croatian Parliament[307] was held in Sacred Heart Cathedral in Sarajevo as replacement for an annual gathering usually held in Bleiburg, Austria, which was canceled due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.[308] At the same time thousands of protesters marched through Marshal Tito street to commemorate victims of the Ustaša regime, and gathered at Eternal flame. Most of Bosnian politicians criticized the Mass held by head of Catholic Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Vinko Puljić. Previously, it was condemned by Bosnia's Serbian Orthodox Church, the Jewish and Muslim communities and several antifascist organizations.[309]

In July 2020, the lower house of the Austrian Parliament adopted a resolution calling on the Ministry of the Interior to consider banning the commemoration in Bleiburg, because of the display of Ustaše symbols.[310] The ban, however, did not occur,[311] and the 2021 commemorative event was held under COVID restrictions, without large gatherings.[312]