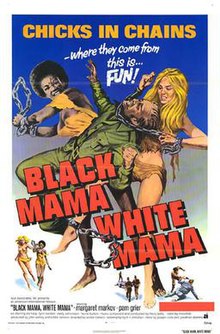

Black Mama White Mama, also known as Women in Chains (US reissue title), Hot, Hard and Mean (original 1974 UK title) and Chained Women (1977 UK reissue title), is a 1973 women in prison film directed by Eddie Romero and starring Pam Grier and Margaret Markov. The film has elements of blaxploitation.[4]

| Black Mama White Mama | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Eddie Romero |

| Screenplay by | H.R. Christian |

| Story by | |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Justo Paulino |

| Edited by | Asagani V. Pastor |

| Music by | Harry Betts |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 87 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$200,000[1] |

| Box office | US$1 million (US and Canada rentals)[2][3] |

The movie was reportedly inspired by the 1958 film The Defiant Ones in which Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis are shackled together similarly to Grier and Markov. Set in an unspecified Latin American country (referred to only as "the island"), the movie was shot in the Philippines for budgetary purposes.[5]

Plot

editBrought to a women's prison in a tropical country resembling the Philippines-set location of the movie, Lee Daniels (Pam Grier) and Karen Brent (Margaret Markov), a prostitute and a revolutionary respectively, butt heads and cause enough trouble to warrant a transfer to a maximum-security prison. They are chained together during the transfer, much to their dismay, and an attack by Karen's rebel friends allows them to escape, albeit still chained together.

The movie chronicles the pair's struggle to evade the army, led by Captain Cruz (Eddie Garcia), who enlists the help of the cowboy gang led by Ruben (Sid Haig). The pair also has competing goals: Lee aims to recover the money she extorted from her former pimp, Vic Cheng (Vic Díaz), and escape by boat, while Karen intends to meet her gun connections on time to prevent them from turning on her rebel friends.

The pair finally bonds, despite their initial hatred for each other, until they are ultimately freed by the rebel leader Ernesto (Zaldy Zshornack). The movie culminates in a violent shootout involving Cheng and Ruben's henchmen (who are rivals), Ernesto's guerrillas, and the army. While Karen is killed in the firefight, Lee escapes on a sailing vessel.

Cast

edit- Pam Grier as Lee Daniels

- Margaret Markov as Karen Brent

- Sid Haig as Ruben

- Lynn Borden as Matron Densmore

- Zaldy Zshornack as Ernesto

- Laurie Burton as Warden Logan

- Eddie Garcia as Captain Cruz

- Alona Alegre as Juana

- Dindo Fernando as Rocco

- Vic Díaz as Vic Cheng

- Wendy Green as Ronda

- Lotis M. Key as Jeanette

- Alfonso Carvajal as Galindo

- Bruno Punzalan as Truck Driver

- Ricardo Herrero as Luis

- Jess Ramos as Alfredo

- Carpi Asturias as Lupe

- Andrés (Andy) Centenera (uncredited) as Leonardo

- Bomber Moran (uncredited) as Vic Cheng's goon.

Production

editThe movie was made by Four Associates Ltd., the company of John Ashley and Eddie Romero.[6] In December 1972, it was acquired by American International Pictures.[7]

The movie takes its inspiration from the story concept of shackling a black character and a white one together introduced by The Defiant Ones (1958). John Ashley says the movie was originally called Chains of Hate and he bought the treatment from Jonathan Demme for $500.[8]

The lead actresses also reprised roles they already knew well. Pam Grier, who plays Lee Daniels, had done several tropical prison films, including The Big Doll House (1971), its non-sequel follow-up The Big Bird Cage (1972), and Women in Cages (1971).[9][10]

Margaret Markov, who plays Karen Brent, had appeared in The Hot Box (1972), which was also a Latin American prison film. All of these movie were shot in the Philippines in accordance with their low budgets.[11] Pam Grier and Sid Haig also appear together in another tropical prison film The Big Doll House (1971) and Grier, Haig, Vic Díaz, and Andrés Centenera appear together in its non-sequel follow-up The Big Bird Cage (1972), which were also both filmed in the Philippines. Grier and Margaret Markov also starred opposite each other in the 1974 movie The Arena (a.k.a. Naked Warriors).[5][12]

The movie was made at the same time as The Twilight People.[8]

Several Volkswagen Country Buggies are used in the movie; these were based on the VW Beetle chassis originally for the Australian market. The Country Buggy was produced locally in the Philippines as the Sakbayan, using VW power plants sourced from either Brazil or Mexico.

Eddie Romero says that Sam Arkoff of AIP called him during the shoot, saying he was unhappy with the lack of coverage. Romero asked Arkoff to have a look at the dailies and see if there was any coverage that he thought was needed. He never heard from Arkoff again after that.[13]

Grier became seriously ill during the making of the movie. "It was a tropical disease you get from ingestion, either from food or from the virus going through your skin in water", she said. "We were in a lot of rivers, rice paddies, where there are leeches and bacteria. So it was just a matter of time before it went through a cut and into your brain – and it could kill you." She was in bed for a month with a temperature of 105 degrees. "I lost my hair, I couldn't see, I couldn't walk. I was dying. The doctor kind of froze me to kill the cell in my brain."[14]

Lynn Borden says she, too, fell ill during filming as well.[15]

Themes

editFeminism and sexuality

editBlack Mama White Mama, despite its exploitative nature, passes the Bechdel test[citation needed] and contains themes of female empowerment. Both of the movies' leads are strong women. Karen Brent is a guerrilla fighter and Lee Daniels masterminds a scheme to screw over the misogynistic pimp, Vic Cheng. Although Karen is the only female present in the guerrilla force, she is essential to their cause, as she is the only one that has the connections to the weapons dealers, and the only one that those dealers trust (Ernesto says "Her contacts would never turn them over to us."). She also is seen firing a gun right alongside Ernesto, the guerrilla leader.[original research?]

James Robert Parish and George H. Hill state that Pam Grier is "an intriguing mixture of pugnacity and femininity, with a heavy dose of world-weary cynicism"[5] despite, according to Bob McCann, the movie itself being "somewhat listless",[16] and the strength of both women outshine most of the male characters.[citation needed] Yvonne Sims states that "it became evident very quickly that Grier's screen presence overshadowed the one-dimensional roles that focused on her physical attributes and the weak storylines in AIP [American International Pictures] productions."[17]

Pam Grier's character Lee also escapes from her former pimp with $40,000 of his money, while the pimp and his henchmen are all killed. Not only that, but when the pair is sexually assaulted by Luis in his work shed midway through the movie, Lee stabs him to death. Cultural critic Nelson George notes, "Pam Grier was a cult figure who was even embraced by many feminists for her ball-breaking action movies. She remains one of the few women of any color in American film history who had vehicles developed for her that not only emphasized her physical beauty but also her ability to take retribution on men who challenged her."[18] Therefore, "Grier...brought a new character to the screen that was instrumental in reshaping gender roles, particularly those involving action-centered storylines." (Simms)[17]

Black Power

editBlack Mama White Mama also contains elements of Black Power, as it was released during the middle of the Black Power era.

The revenge that Lee Daniels gets on her former pimp is nothing short of Black Power, and "1973 marked the first time that audiences saw African American women in non-servitude roles."[17]

Lee also wears her hair in an Afro. As a "Killer Dame" (along with Tamara Dobson, Teresa Graves, Jean Bell, et al.), "It was a goodbye to the headscarves worn by Mammy and the wavy hair of the Exotic Other, and a refreshing and political greeting to the woman with a natural hairstyle modeled, according to [film scholar Cedric Robinson], from civil rights heroines such as Angela Davis." Moreover, her very portrayal of an action heroine "represented the antithesis of the Mammy."[17]

In the beginning of the movie, Lee resists the white matron of the prison's lesbian advances, even though she knows that her life in prison will be a lot easier if she engages with her. Karen, on the other hand, readily submits to the matron's advances so that she does not have to work in the field, placing a greater burden on the other prisoners. This greatly irks Lee, as she sees it as a selfish move. Though both women play strong roles, Lee is unique in that she never lets a single character walk over her. The movie may be symbolic in that Lee is mentioned first in the title and the credits. The ending also implies that her strength exceeded Karen's.

In another scene, Black Power is alluded to by a surprising source, Karen. During a fight with Lee over which direction to go while shackled together, she exclaims, "We're trying to set this island free. Christ, you're black, you understand, don't you?" This line of thought is not pursued further, but the scriptwriters (one of which was none other than Jonathan Demme himself, who later won an Academy Award for directing The Silence of the Lambs), were clearly making the connection between revolutionary actions occurring in Latin America and the Black Power Movement in the United States. Demme and Joseph Vila could have been referring to a number of Latin American revolutions, including the Black Power Revolution in Trinidad in 1970. This particular connection would make a lot of sense, because at the time in Trinidad, guns were not "readily available",[19] and a major plot point of this movie is that the guerrillas need guns in order to succeed and Karen's American weapons contacts are deemed essential for their cause.

Release

editOne advertisement for the movie included the tagline "Chicks in chains...and nothing in common but the hunger of 1,000 nights without a man!"[20]

Reception

editBox office

editAshley recalls being unhappy when AIP wanted to change the title to Black Mama White Mama. "[It was] really left field. I didn't care for it. As it turned out, that was the most successful theatrical movie I have ever done, in terms of hard dollars in my pocket."[8]

Critical

editThe movie, like many blaxploitation movies, was a B-movie produced on a low budget and received mixed reviews.

"So bad it's good", said the Los Angeles Times.[21]

Variety magazine said that "Performances ranged from bad to mediocre." Josiah Howard writes in Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide that the movie was "a lively and well-done women's prison yarn", but that it "somehow never really hits its mark", largely because "the filmmakers do little to distance themselves from the tired trick...of having key characters shackled together for almost the entire length of the picture." However, the pairing of Pam Grier and Margaret Markov was "a hit with audiences",[22] as they played off each other well. Variety praised Eddie Garcia, saying that he "rises above the material by studious underplaying".[5]

"That film wasn't half bad", reflected Romero years later. "There are scenes in there I wasn't ashamed of. But some of those "cult" films, Beyond Atlantis and The Bride of Blood Island – the worst things I ever did. Ayy!!!!... Pam Grier was the gamest actor I ever worked with. She was willing to do anything- jump off a cliff, whatever. I'd be talking to a stuntwoman and Pam would say, 'Oh I can do that.' Ha! She was very good. And Margaret Markov was very good."[23]

Soundtrack

editThe soundtrack received praise. Howard comments, "Harry Bett's superior ambient music soundtrack (available on CD) is much more sophisticated than the movie that it was created for."[22]

- Main Title/Bus Ride

- Follow Me

- Day in the Oven

- Ambush

- Girls Exit Oven

- Bus Stop

- Police Check Point

- Luis' Work Shed

- Blood Hounds

- Challenge and Battle

- Ambush, Escape and Roundup

- End Credits[24]

Legacy

editThe movie is screened in the John Sayles film Lone Star (1996). Sayles said "Even that [movie] is about people of different races being chained together whether they want to or not."[25]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lamont, John (1990). "The John Ashley Filmography". Trash Compactor (Volume 2 No. 5 ed.). p. 26.

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1973", Variety, January 9, 1974, p. 60

- ^ Donahue, Suzanne Mary (1987). American film distribution : the changing marketplace. UMI Research Press. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-8357-1776-2.

- ^ "Black Mama, White Mama". Dvdtalk.com. Retrieved October 26, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Parish, James Robert., and George H. Hill. Black Action Films: Plots, Critiques, Casts, and Credits for 235 Theatrical and Made-for-Television Releases. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 1989. Print.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (December 6, 2019). "A Hell of a Life: The Nine Lives of John Ashley". Diabolique Magazine.

- ^ Murphy, M. (December 2, 1972). "MOVIE CALL SHEET". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 157121133.

- ^ a b c Lamont, John (1992). "The John Ashley Interview Part 2". Trash Compactor (Volume 2 No. 6 ed.). p. 6.

- ^ Tuchman, M. (July 28, 1974). "A new dimension for the girl gang genre". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 157528447.

- ^ Monaco, James, and James Pallot. The Encyclopedia of Film. New York: Perigee, 1991. Print.

- ^ Koven, Mikel J. Blaxploitation Films. Harpenden: Kamera, 2010. Print.

- ^ Broeske, P. H. (June 16, 1985). "GOOD TASTE NO BARRIER TO MAKING PROFITABLE FILMS ON WOMEN IN PRISON". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 290839815.

- ^ Leavold, Andrew (2006). "Strong Coffee with a National Treasure:An Interview with Eddie Romero". Cashiers du Cinemart.

- ^ Jaggi, M. (March 7, 1998). "Twentieth-Century Fox as the glamorous, gun-slinging Foxy Brown, Pam Grier was both sex symbol and radical icon, the undisputed queen of the seventies blaxploitation flick. Twenty-five years on, she's the eponymous star of Quentin Tarantino's new film Jackie Brown. The role guarantees overwhelming fame. But she's more than ready to handle it". The Guardian. ProQuest 245229744.

- ^ Tate, James M. (May 12, 2013). "LYNN BORDEN ON BLACK MAMA, WHITE MAMA". Cult Film Freaks.

- ^ McCann, Bob. Encyclopedia of African American Actresses in Film and Television. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2010. Print.

- ^ a b c d Sims, Yvonne D. Women of Blaxploitation: How the Black Action Film Heroine Changed American Popular Culture. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2006. Print.

- ^ Gregg Braxton (August 27, 1995). "She's Back and Badder Than Ever". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Victoria Pasley (November 2001). "The Black Power Movement in Trinidad: An Exploration of Gender and Cultural Changes and the Development of a Feminist Consciousness". Journal of International Women's Studies. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "Black Mama White Mama". The Baltimore Afro-American. Baltimore, Maryland. UPI. May 26, 1973. p. 18.

- ^ Thomas, K. (March 22, 1973). "MOVIE REVIEW". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 157052860.

- ^ a b Howard, Josiah. Blaxploitation Cinema: The Essential Reference Guide. Godalming, Surrey, England: FAB, 2008. Print.

- ^ SERVER, LEE, and EDDIE ROMERO (1999). "EDDIE ROMERO: Our Man in Manila". Film Comment. Vol. 35, no. 2. p. 49. JSTOR 43455360.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Monkey Hustle / Black Mama, White Mama Soundtrack". Amazon.

- ^ Smith, G. (1996). "John Sayles: 'I don't want to blow anything by people'". Film Comment. Vol. 32, no. 3. p. 56. ProQuest 210261893.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)