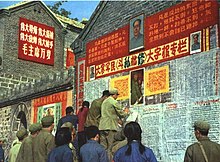

Big-character posters (Chinese: 大字报; lit. 'big-character reports') are handwritten posters displaying large Chinese characters, usually mounted on walls in public spaces such as universities, factories, government departments, and sometimes directly on the streets. They were used as a means of protest, propaganda, and popular communication. A form of popular political writing, big-character posters did not have a fixed format or style, and could appear in the form of letter, slogan, poem, commentary, etc.

| Big-character poster | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 大字報 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大字报 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | big-character reports | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Though many different political parties around the world have used slogans and posters as propaganda, the most intense, extensive, and varied use of big-character posters was in China in various political campaigns associated with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Big-character posters were first used extensively in the Hundred Flowers Campaign, and they played an instrumental role in almost all the subsequent political campaigns, culminating in the Cultural Revolution. Though the right to write big-character posters was deleted from the Constitution of the People's Republic of China in 1980, people still occasionally write big-character posters to express their personal and political opinions.

History in China

editPrototypes before 1949

editDazibao have been used in China since imperial times, but became more common when literacy rates rose after the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. They have also incorporated limited-circulation newspapers, excerpted press articles, and pamphlets intended for public display. Big-character posters can be seen as part of a long tradition of using writings to convey information and express dissent in public. Wall posters have been used in China to publicly announce royal edicts, pronouncements, and various orders since at least the Zhou Dynasty (1046 BC - 771 BC), when posters were the only means of communication between the emperor and his people.[1] Local governments also used such posters, for instance to announce news or describe the physiognomy of wanted criminals.[1][2] Documentation of posters used to express political dissent can be found as early as the Han Dynasty. Around 172 AD, a poster attacking the powerful eunuchs appeared on the gate of the Imperial Palace.[3]

In the Republic of China, increased popular literacy enabled a more effective use of public posters as a form of political propaganda. Posters and other forms of public writings were frequently employed to express nationalist sentiment.[4] During the May Fourth Movement in 1919, Peking University students were enraged by the Treaty of Versailles, which handed German-occupied territory in China to Japan after World War I and decided to hold a rally in protest. "Inflammatory notices" on the campus bulletin board announced their plan.[5] When Sun Yat-sen died in 1925, and during the lying-in-state held in Central Park in Beijing, people spontaneously hung thousands of funeral scrolls around the park, which were often inscribed with a couplet expressing their grief and respect for the leader of the Xinhai revolution.[6] Posters were also used extensively in 1925 during the May 30th Movement, for instance in urging patriotic citizens to stop using foreign products.[7]

At the time, the Kuomintang (KMT, or the Chinese Nationalist Party) used slogans and posters in their political propaganda. Some early posters share the visual aesthetics of later big-character posters.[8] For instance, a poster printed by the Political Department of the General Headquarters of the National Revolutionary Army led by KMT is dominated by big characters written in the center. The sentence read: "If the peasants want to plough their fields, they must help the revolutionary army." Compared to contemporary designs, which were often more flamboyant and distracting, this poster has a simple grotesque-style border that directs the reader's attention to the words.[9] Although the poster was printed, the characters appear as forceful handwritings that convey a heightened sense of immediacy.

Big-character posters in the Yan'an period

editInspired by the Soviet Union, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) also used wall newspapers and posters in their propaganda campaign, as they could be easily produced and reproduced and were written in accessible language conducive to mass mobilization.[10] It was commonly believed that big-character posters originated in Yan'an, the CCP headquarter during the Anti-Japanese War and the subsequent civil war.[11] They not only disseminated news and communist ideas but were also used to purge party officials during the 1942 Rectification Movement.[1] During this early use of big-character posters, both the target and the degree of criticism were strictly controlled by the CCP party units.[12] However, occasionally, though rarely, people also used big-character posters to criticize the CCP. On March 23, 1942, Wang Shiwei, a 36-year-old pro-Communist journalist and writer, posted an essay titled "Two Reflections". Written in large characters, the essay criticized certain party leaders for repressing forms of political dissent.[13] In the next week, several other posters similarly critical of the party also went up, which triggered intense debate among the party leadership.[13] The party did not appreciate such public criticism of its operation, and the writers were punished. In particular, Wang was accused as a "Trotskyist spy" and beheaded in 1947.[14] In 1945, during The 7th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong reflected on Wang's big-character poster: "We were defeated by him. We acknowledged our defeat and worked hard at rectification."[15] In 1957, when Mao Zedong had started to use big-character posters to mobilize the masses during the Hundred Flowers Campaign, he looked back to the Yan'an period in his talk at the supreme state conference: "A few big-character posters were written in the Yan'an period, but we didn't promote it. Why? I guess maybe we were a bit foolish back then."[16]

1950s: Big-character posters in the Hundred Flowers Campaign and the Great Leap Forward

editIn late 1956, Mao Zedong believed that internal contradictions within the socialist society and within the party leadership, such as issues of subjectivism, bureaucratism, and secretarianism, must be solved before they develop into serious antagonism that requires more violent and radical measures.[17][18] To expose these contradictions, Mao was determined to create an open atmosphere in which people may freely air any constructive advice.[19] In February 1957, he launched the Hundred Flowers Campaign, which attempted to mobilize the masses, especially non-party intellectuals, to voice their concerns and contend with each other.

However, as criticism started to target Mao's judgment and question whether China should be led by CCP and whether China should adopt the socialist path, Mao decided that it was enough.[20] On May 15, 1957, he wrote an article "Things are starting to change", which was immediately passed around party cadres but not yet made public.[21] In the article, Mao insisted that "In recent days the Rightists in the democratic parties and institutions of higher education have shown themselves to be most determined and most rabid... To date, the Rightists have yet to reach the climax of their attack, and they are going at it in high spirits... We shall let the Rightists run amuck for a time and let them reach their climax. The more they run amuck, the better for us... Why is such a torrent of reactionary, vicious statements being allowed to appear in the press? To let the people have some idea of these poisonous weeds and noxious fumes so as to have them uprooted or dispelled."[22]

The first critical big-character poster was posted on May 19, 1957, on the walls of the dining hall of Peking University, after Mao made up his mind that all those criticizing the party would be encouraged to speak up only to be eliminated later.[23] This first poster was not exceptionally radical. It questioned how representatives to the National Congress of Youth League were selected and implied that the responsible cadres were nepotistic.[24] 500 more posters followed in the next three days, and the number continued to grow.[23] The content of these big-character posters varied from criticizing the "three evils" (subjectivism, bureaucracy, and sectarianism), criticizing dogmatism in teaching, demanding freedom to form communities and societies, and urging the cancellation of bans on books.[25][26] One poster by Long Yinghua from the philosophy department suggested that a section of the university wall should be designated as a forum for such democratic discussion, and hence the Democracy Wall was born in Peking University.[27] Some of the more radical posters questioned the primacy and legitimacy of CCP and demanded absolute democracy.[28] Liu Qidi's poster "Hu Feng is certainly not a counter-revolutionary" challenged the accusations of the intellectual Hu Feng three years ago in an earlier rectification campaign, which essentially questioned the judgment of Mao and CCP.[29]

Most party media were silent about the student movement. "The Democracy Wall in Peking University", written by Liu Guanghua from Wenhui Daily, was one of the few articles sympathetic towards it.[30] Some posters quoted in his article had evident "anti-party" and "anti-socialism" sentiment. Liu's essay encouraged nationwide writing of big-character posters, which started to appear in universities in Nanjing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, etc. This first wave of big-character posters was not welcomed by university party cadres. For instance, Cui Xiongkun, the deputy secretary of CCP in Peking University, stated: "big-character is not the best practice."[31] Party authorities urged students to stop posting, which only generated more posters denouncing their restriction of freedom of expression. The Peking University Party Committee eventually gave consent to the posting of big-character posters.[32]

Factory workers in the Hundred Flowers Campaign also used big-character posters to criticize bureaucratism in the running of factories. For instance, in 1956, Li Lesheng, a deputy chairman of a trade union, wrote a big-character poster against local party secretary Deng Song, whose policies were not welcomed by workers and other trade-union cadres.[33]

The student unrest became the last straw for Mao Zedong, who was already impatient with the radical criticism aired by non-party intellectuals.[34] In the first week of June 1957, Mao launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign. Those critical of the party or the government were labeled "rightists" or "capitalist-roaders" and were punished for attempting to sabotage the dictatorship of the proletariat.[35][36] Their use of big-character posters was also condemned. On June 14, People's Daily criticized Wenhui Daily's sympathetic coverage of big-character posters.[37] On July 1, People's Daily called the Wenhui Daily editorial team a "rightist system" and characterized big-character poster as an evil weapon used by rightists against the party.[38] Big-character posters critical of Mao or CCP soon vanished.[39]

While the content of this first wave of big-character posters irritated Mao Zedong, he was impressed by the medium's effectiveness in engaging the masses, and he decided to adopt it for his political goals.[40] In June 1957, Mao already observed: "According to Beijing's experience, posting dazibao in party organs and universities can, first, expose faults such as bureaucratism; secondly, expose those who have reactionary or incorrect thoughts; thirdly, train party members and those still in the middle."[41] In July 1957, Mao further redefined big-character posters as "a revolutionary form that is beneficial to the proletarian and not to the bourgeoise". He reasoned that "the fear of big-character poster is unfounded", since it would only "expose and solve contradictions and help people make progress."[42]

Big-character posters were coopted by the party as a useful weapon against the rightists, many of whom were arrested for posting critical posters. During the Anti-Rightist Campaign, out of the 500,000 people designated as rightists, many were exposed and condemned by big-character posters.[43] Local party organizations also tried to engage the public in the writing of big-character posters against class enemies.[44] At first, people were unmotivated, fearing that their writings would be used against them in the future. In October 1957, Mao wrote another essay, "Be activists in promoting the revolution," which established the legitimacy of big-character posters as a form of mass struggle. He described big-character posters as "the most suitable for the masses to take the initiatives and to raise their responsibility...as they fully exercise socialist democracy."[45] In the same month, official media such as People's Daily and Beijing Daily started promoting big-character posters.[46] In an attempt to mobilize the writing of big-character posters in factories, leading party cadres including Mao Zedong, Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai, and Zhu De all went to different Beijing factories to read big-character posters.[47]

With such explicit encouragement, big-character posters finally flourished in every major Chinese city.[48] In a factory in Beijing, 110,000 big-character posters were posted within two weeks.[49] In Shanghai, a work unit of only 32000 employees produced 40,000 posters in August 1957.[50] In Tianjin, 300,000 big-character posters were written in only twenty days.[51] Between late October and mid-November, 5,000 posters appeared in Chengdu Industrial College.[52] Not all of the posters were critical, as some simply praised the governance of CCP.[53] In some places, the writing of posters were highly organized, with an editorial board, a production center, a distribution center, and even a correspondent network.[54]

According to official media, big-character posters were effective not only in raising but also in solving problems. Issues that had remained for years were immediately solved once brought to public attention in big-character posters.[55] However, the content and form of big-character posters were closely monitored by the party and nothing that could jeopardize its authority would be published. According to PRC legal scholar Hua Sheng, big-character posters were at most a token of free expression which gave the public an illusion of participation.[48] Indeed, though miscellaneous local problems were exposed, opinions expressed in these big-character posters tended to be homogeneous in their unanimous support for Mao and the Party, and is thus similar to other forms of political propaganda.[48]

Mao Zedong continued to promote the use of big-character posters in 1958 during the Great Leap Forward.[56] In April 1958, he advised that big-character poster could be used "wherever the masses congregate. Wherever it has been widely used, people should continue using it."[57] Posters appeared in party organs and administrative offices, revealing instances of corruption and waste.[58] Universities remained centers of producing big-character posters. Students frequently attacked their professors for valuing professionalism more than political consciousness.[59] Many professors, who didn't write any poster in previous campaigns, started reading and writing big-character posters, mostly as a means of self-criticism.[60] Big-character posters were also mobilized against "bourgeoise individualist behavior," which was essentially any demand for academic independence, personal freedom, individual economic benefit, etc.[61]

During the Great Leap Forward, big-character posters were also used in rural villages to rectify the operation of People's Communes and to promote production.[62] Many news articles claimed that big-character posters had motivated farmers and contributed to an increase in production. For instance, more rice seedlings were allegedly transplanted after the posting of big-character posters in the Jingxi County in Guangxi.[63]

People also wrote big-character posters to support China's sovereignty. When the US navy moved into the Taiwan Strait in 1958, numerous big-character posters were produced in support of Zhou Enlai's declaration on September 4 that no foreign aircraft or military vessels may enter China's territorial sky and waters without permission. According to People's Daily, hundreds and thousands of posters were produced by students from the Beijing No.4 High School within 10 minutes of the airing of the declaration.[64]

An unbelievable number of big-character posters were allegedly produced during the Great Leap Forward. For instance, in the anti-waste and anti-conservatism campaign, 90,000 big-character posters appeared in Peking University in a day.[65] According to Wenhui Daily, teachers from Shanghai's Xuhui District produced 800,000 big-character posters between February 24 and February 26, 1958.[66] Shanghai claimed that in 1958 it created a total of a billion big-character posters.[67] This emphasis on quantity was a general tendency shared across all production units and industries during the Great Leap Froward.

The enthusiasm of writing was unsustainable once every issue had been discussed and every problem had been exposed after a period of fervent posting.[68] To maintain their production, societies of big-character posters were set up in different party institutions to organize the posting and discussion of big-character posters.[68] In the 1964 Socialist Education Movement, big-character posters were again employed. According to Göran Leijonhufvud, one of his informants recalls that posters were everywhere in his village in Guangdong Province. Even illiterate people were expected to generate big-character posters by asking people to write for them.[69] Nevertheless, the writing of big-character posters declined in the early 1960s.

Big-Character posters during the Cultural Revolution

editBig-Character posters were among the "four bigs," political instruments which the masses used widely during the Cultural Revolution.[70] The other three referred to great airing of opinions (daming), great freedom (dafang), and great debate (dabianlung).[70]

"What are Song Shuo, Lu Ping, and Peng Peiyun up to in the Cultural Revolution"

editA key trigger in the Cultural Revolution was the publication of a "What are Song Shuo, Lu Ping, and Peng Peiyun up to in the Cultural Revolution" on 25 May 1966, coauthored by seven cadres from Peking University's philosophy department, including Nie Yuanzi (聂元梓; 聶元梓), Song Yixiu, Xia Jianzhi, Yang Keming, Zhao Zhengyi, Gao Yunpeng, Li Xingchen. The poster was typically referred to as the first big-character poster written during the Cultural Revolution, but two days earlier two senior cadres in the Academy of Sciences' Department of Philosophy and Social Sciences (today's Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) already wrote a big-character poster against their directors.[71]

These seven people had many reasons to write this poster, one of them being their personal grudge against two of the principal targets, Song Shuo and Lu Ping. In 1964, during the Socialist Education Movement, Lu Ping, President of Peking University and Secretary of the University Party Committee, was criticized by leftist activists as a capitalist.[72] However, when the campaign started to go out of control, Peng Zhen, First Secretary of the Beijing Municipal Committee and Major of Beijing, intervened and sent a work item that included his Deputy Secretary Deng Tuo to Peking University to restore order.[73] In March 1965, Deng Xiaoping also stepped in and reinstalled Lu Ping.[72] Socialist education activists were criticized, including those in the philosophy department, Nie Yuanzi, Zhang Enci, Kong Fan, and Sun Pengyi.[72] In particular, due to her fierce attack against Lu Ping, Nie Yuanzi was severely criticized in 1965.[73] Yet on May 19, 1966, CCP announced the May 16 Circular authored by Mao. It attacked Peng-Luo-Lu-Yang (Peng Zhen, Luo Ruiqing, Lu Dingyi, Yang Shangkun) as an Anti-Party Clique and dismissed the Five-Person Cultural Revolution Small Group led by Peng.[72] Those who criticized socialist education activists were openly denounced. Nie Yuanzi and Zhao Zhengyi saw an opportunity to reinstate their position and on May 23, they decided to write a big-character poster, "the best way of attacking the school's party leadership."[74]

They easily found something to attack. Since September 1961, Deng Tuo, Wu Han (deputy mayor of Beijing), and Liao Mosha (Head of the Beijing United Front Work Department) co-authored the column "Sanjiacun Zhaji" (Three-Family Village Reading Notes) on the party magazine Qianxian (Frontline). The 67 published essays included some veiled criticism against Mao. In May 1966, under the direction of Jiang Qing, three articles were published on Jiefang Daily and Guangming Daily against the column, which was characterized as an "anti-party, anti-socialism big poisonous weed" that intended to overthrow the dictatorship of the proletariat and restore capitalism in China.[75] While the entire country was agitated against the column and its writers, Peking University did not support their blind criticism. On May 14, 1966, Lu Ping repeated Song Shuo's (vice-president of the Beijing Municipal Committee's University Department) word, who demanded that the party organization in the university "strengthen their leadership and hold their post" to lead the agitated masses to "the correct path".[76] They insisted that the refutation of anti-party and anti-socialist rhetoric should happen on the theoretical level and must rely on reasoning. Instead of posting big-character posters, they encouraged people to lead small group discussions and write small-character posters (xiaozibao) and critical essays, since big plenary sessions could not lead to a profound and specific revolution.

Nie et al. found fault with Lu Ping and Song Shuo's attempt at limiting the form and scope of the masses' political participation. Their big-character poster[76] claimed that the university was controlled by bourgeois anti-revolutionaries.It raged against the university for putting down faculty and students' strong revolutionary demand and for its reluctance to support the Cultural Revolution wholeheartedly. It attacked Song Shuo, Lu Ping, and Peng Peiyun as a "bunch of Khrushchev-type revisionist elements" for going against the Central Committee and Mao Zedong, and labeled their preference for theoretical discussion as revisionist. It also criticized their discouragement of big-character posters and big planetary meetings, framing any limitation on mass participation as suppression and opposition to mass revolution.

Song Yixiu purportedly wrote the first draft on May 24, 1966, and Yang Keming revised the poster.[72] Though Nie Yuanzi put her name first, she was only marginally involved in the actual writing of the poster.[74] Nie only added three slogans at the end of the text: "Defend the party center! Defend Mao Zedong Thought! Defend the dictatorship of the proletariat!" [74] She did meet with Cao Yiou on May 25 and asked for her approval to put the poster up.[74] At the time, Cao Yiou was sent by Kang Sheng (a leading member of the Central Case Examination Group and adviser to the Central Cultural Revolution Group) to Peking University as the head of a seven-person central investigation team, the apparent intention of which was to review the progress of Peking University's academic criticism. Nevertheless, they had already decided that the criticism was not on the right track and Lu Ping would be held responsible, and Cao's real task was to mobilize the masses against the school's party leadership.[77] She thus had no reason to turn Nie Yuanzi down. At two o'clock in the afternoon, the poster was put up on the eastern wall of the university's canteen.[74]

Within a few hours of its posting, more than a hundred similar big-character posters targeting Lu Ping and Peng Peiyun also appeared, mostly written by Nie's supporters.[78] In less than half a day, the campus was covered by big-character posters. According to a witness account, those who supported the poster and those who opposed it were evenly balanced.[72] However, according to Lin Haoji, more posters refuted the first poster.[79] Allegedly, Lu Ping also engaged his supporters to write big-character posters that denounced Nie Yuanzi's action as an "opposition to the Party Central Committee."[80] Vice President Huang Yiran urged Nie to remove the poster, but Nie refused.[81]

Mao Zedong was not in Beijing at the time. Liu Shaoqi and other leaders tried to control the movement by issuing an eight-point directive restricting the posting of big-character posters, yet the guidelines were not strictly followed by the students.[82] On May 25, Li Xuefeng, the newly appointed First Secretary of Beijing, visited Peking University at midnight and exhorted students and party members that they must "struggle in an orderly way instead of scrambling everything up."[83] Zhou Enlai also sent Zhang Yan, deputy director of the State Council's Foreign Affairs Office, to caution the students that since foreign students were present on campus, they should refrain from putting up big-character posters in public space.[84] After meeting with the Central Committee, Liu Shaoqi, Zhou Enlai, and Deng Xiaoping decided to send down work teams to various universities to further control the movement, and Mao Zedong initially approved their decision.[81]

To support Nie Yuanzi and other student activists against the work teams, Kang Sheng sent a copy of the poster to Mao Zedong, who was enjoying his vacation in Hangzhou.[85] Mao read it on June 1 and wrote an instruction: "This text could be published by the Xinhua News Agency in all the national journals and magazines. It is absolutely necessary. Now we can smash the reactionary stronghold that is Peking University. Do so as soon as possible! The big-character poster from Peking University is a Marxist-Leninist big-character poster. It must be immediately broadcast and immediately published."[86] On June 2, People's Daily reprinted the poster in its entirety, together with Chen Boda's article "Hail Peking University's Big-Character Poster."[87] Chen supported the main ideas proposed in the Peking poster and further criticized Lu Ping, Song Shuo, and Peng Peiyun as reactionary, anti-party, and anti-socialist. He also insisted that every proletarian revolutionary must follow CCP's discipline and unconditionally accept the leadership of the Central Committee.

The national reproduction of Nie et al.'s big-character poster immediately activated students.[88] Between June 1 and June 6, more than 50,000 big-character posters were posted in Peking University,[89] and 65,000 posters appeared in Tsinghua University.[90] In the Post and Telecommunications Sector in Beijing, each person on average wrote more than 7 big-character posters in June, 1966.[91] This first wave of writing mainly targeted school leaders and party committee members who previously did not support students' posting of big-character posters.[92]

More people went to the universities to read big-character posters, and many middle school students went to learn how to write a big-character poster.[93] According to the celebrated Chinese writer Ji Xianlin, "every day hundreds of thousands of people came...in addition to people, the walls, the ground, and the trees were covered by big and small character posters, and they all have the same content, supporting the first Marxist-Leninist big-character poster."[94] The press continued to celebrate big-character poster. On June 21, People's Daily published "Revolutionary Big Character Posters are the Demon-Detectors to Expose All Ox-Demons and Snake- Spirits," which characterized big-character poster as an effective weapon against "ex-demons and snake-spirits" and asserted that all true revolutionaries must welcome big-character posters and anyone who suppressed its writing and posting was a counter-revolutionary conservative.[95]

At the time, the work teams initially sent by Deng Xiaoping, Liu Shaoqi, and Zhou Enlai were still in the universities, and the tension between work teams and student activists escalated. Though work teams seemingly encouraged students to criticize bourgeois or revisionist teachers, they were given the mandate to monitor the most outspoken teachers and students, and unorganized and unsupervised accusations and struggles against individual teachers and cadres were criticized.[96] The students, who assumed that the work teams should support all their revolutionary effort, became dissatisfied with the imposed restrictions and wrote big-character posters against the work teams.[97] In late July, Mao Zedong intervened. He insisted that those who wrote big-character posters should not be arrested, even if they wrote reactionary slogans.[98] He urged all cadres to go to Peking University to read big-character posters and encourage the students.[99] On July 24, Mao finally ordered all work teams to withdraw from colleges and middle schools.[100]

The central target of Nie et al.'s poster, Lu Ping, was eventually dismissed. The entire Peking University Party Committee was reorganized, and Nie Yuanzi became an important member of the new committee.[88] In the Eleventh Plenary Session of the Eighth CCP Central Committee held between August 1 and 12, 1966, Nie Yuanzi and other "revolutionary representatives" were invited.[47]

Mao Zedong's first big-character poster

editIn the Eleventh Plenary Session of the Eighth CCP Central Committee, Liu Shaoqi claimed full responsibilities for the work teams' mistakes.[101] Yet Mao Zedong was dissatisfied, as he launched a more severe criticism against Liu Shaoqi and the work teams and alleged that all those who failed to support the student movement should be dealt with.[102]

Mao Zedong was determined to remove Liu Shaoqi from his position. On August 5, he wrote "Bombard the headquarters—my big-character poster", which was distributed to the plenum two days later.[103] Strictly speaking, this was not a big-character poster, as it was never actually mounted on a wall[104] but draught down on an old Beijing Daily.[105] Perhaps Mao intentionally appropriated the name to borrow its spontaneous and rebellious connotation.[106] Though the poster only vaguely targeted "some leading comrades" who had "enforced a bourgeois dictatorship and struck down the surging movement of the great Cultural Revolution of the proletariat", everyone at the time knew that the person under attack was Liu Shaoqi.[103]

Originally, the poser was only supposed to circulate among participants in the Plenum, but its content was immediately leaked.[107] This was the first time that Mao Zedong's profound disagreement with Liu Shaoqi was made public, and students quickly picked up the signal. On August 22, 1966, the first poster against Liu Shaoqi appeared, in which a Tsinghua University student attacked Liu Shaoqi for being oppositional to Mao Zedong thought.[108] Millions more similar big-character posters were posted in Beijing in the next several months.[109] Mao Zedong was ambivalent about such public opposition against Liu Shaoqi. Although Mao wanted to eliminate Liu as a powerful political rival, he still treated this problem as internal to the party. On October 24 and 25, he stated that it was not good to post big-character posters against Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping on the streets, as they should not be completely stricken down.[110] However, the situation was impossible to control, and big-character posters against Liu Shaoqi still appeared in the public.

The eleventh Plenum not only effectively removed Liu from his position, but the "Sixteen Directives" was also ratified at the Plenum, the fourth directive of which encouraged the masses to "make fullest use of big-character posters."[111] The official endorsement of big-character posters triggered widespread fervor. Millions of people wrote big-character posters, which could be found almost everywhere in the nation, from urban cities to rural villages, from university campuses to factories, from government offices to the streets.[112] In Changsha, the walls of the grey buildings along the main streets were colored white by paper.[113] After the Red Guards went to the country to "integrate with the masses", workers and peasants also started to write big-character posters. In Shanghai, in the propaganda sector alone, around 88,000 big-character posters attacked more than 1300 people by June 18.[90]

In the early years of the Cultural Revolution, big-character posters were pasted on the trains from mainland China to Hong Kong.[114] Even foreign experts were influenced by the atmosphere and wrote big-character posters to complain about their privileged treatment and lack of political participation.[115]

The movement quickly went into chaos. On October 25, 1966, Mao Zedong himself described the publishing of Nie Yuanzi's big-character poster and his writing of a big-character poster as a "mistake", but he still believed that the chaos was necessary to bring people's attention to the critical issue.[116] In November and December 1966, more senior party leaders were criticized, including Deng Xiaoping, Zhu De, and Zhou Enlai.[117] This aimless wave of attack was labeled the "evil wind of November and December."[118]

"On Socialist democracy and the legal system" (1974)

editIn the mid-1970s, big-character posters critical of the Cultural Revolution and Mao Zedong began to emerge, the most famous one of which was "On Socialist democracy and the legal system," a 20,000-word poster written on 64 large pieces of paper, posted on a busy downtown street in Guangzhou in November 1974.[119] It was written by Li Zhengtian, a student from the Guangzhou Art Academy, Chen Yiyang, a high-school student, and Wang Xizhe, a worker, under the collective pseudonym Li-Yi-Zhe. It began with a nominal celebration of some positive aspects of the Cultural Revolution but quickly went on to criticize the concurrent lack of democracy and a robust legal system.[120] It called the situation "a rehearsal for socialist-fascism in our country", with Lin Biao "the rehearsal's chief director." In the end, the poster called for democracy, socialist legality, and revolutionary and personal rights.

The poster found a sympathetic audience, but the central authority urged the Guangzhou Revolutionary Committee to denounce the poster.[121] What the party found especially threatening was its implicit rejection of a privileged party stratum that would rule above the people.[122] The Party Committee of Guangdong Province labeled the poster "a counter-revolutionary big-character poster," and called its writers part of "a counter-revolutionary clique."[123]

Perhaps Li-Yi-Zhe's call for socialist legality did strike a chord, as in 1975, the first Constitution of the People's Republic of China was formulated. The right to put up big-character posters was listed as one of the "Four Great Freedoms." Article 13 states that the right to use big-character posters in political movements was protected by the state, as long as they "help consolidate the leadership of the Communist Party of China over the state and consolidate the dictatorship of the proletariat."[124]

Big-character posters used against the Gang of Four

editThroughout the Cultural Revolution, some big-character posters were used against the Gang of Four. In 1970, during the One Strike-Three Anti Campaign, local authorities were unclear about who they should attack, and sometimes even Jiang Qing was criticized as a revisionist.[125]

In 1976, when the Gang of Four decided to go against the newly reinstated Deng Xiaoping, they encountered strong resistance. In Sichuan, Deng's home province, big-character posters praised Deng Xiaoping and questioned the motivation of the Gang of Four.[126] After the death of Zhou Enlai, in the April 5 Tiananmen Incident, many big-character posters attacked the Gang of Four.[127]

Big-character posters in the 1980s

editThe writing of big-character posters continued after the Cultural Revolution. As Deng Xiaoping gradually ascended to power, he was initially tolerant of big-character posters or the public expression of political dissent. On November 27, 1978, he said: "[The presence of big-character poster] is a normal phenomenon and an indication of stability in our country. Writing big-character posters is permitted by our constitution. We have no right to deny [the masses] this right or criticize them for promoting democracy by putting up big-character posters. If the masses feel some anger, we must let them express it."[128] The right to write big-character posters, along with the other "Four Great Freedoms", was kept in the 1978 Constitution. In Chapter 3, "The Fundamental Rights and Duties of Citizens", Article 45 reinstates: "Citizens enjoy freedom of speech, correspondence, the press, assembly, association, procession, demonstration and the freedom to strike, and have the right to "speak out freely, air their views fully, hold great debates and write big-character posters."[129] However, compared to the 1975 version, the emphasis on their use for "socialist revolution" was removed. Ye Jianying commented on the revision, insisting that these rights remained dependent upon one's compliance with the socialist system and CCP's leadership and that this right was only granted to ensure democracy under the leadership of the proletariat.[130]

Between 1978 and 1979, big-character posters posted on the Xidan Democracy Wall stirred national attention and controversy. The Xidan Democracy Wall was a brick wall in Xidan, a shopping district in Beijing at the intersection of West Chang'an Street and Xidan North Street. After 1976, although the Cultural Revolution was criticized, Mao Zedong's reputation in general and the CCP's fundamental authority were deemed unquestionable by the new regime, which caused some discontent among those who suffered during the past ten years.[131] In addition, the government failed to promptly address every victim's request for official rehabilitation and reparation.[132] Thousands of people traveled to Beijing to petition for their cases to be reevaluated, and many publicized their sufferings in the form of big-character posters.[132] It was reported that at one time around 40,000 people went to the Democracy Wall to post, read, and discuss big-character posters.[133]

If the first few posters only retold personal stories, the content of big-character posters soon became bolder, and some began to attack the Cultural Revolution, the Gang of Four, Mao Zedong, and finally Deng Xiaoping.[134] One of the most famous was "The Fifth Modernization", whose bold call for democracy brought instant fame to its author, Wei Jingsheng.[135] On December 5, 1978, Wei Jingsheng, a 28-year-old electrician at the Beijing Zoo, put up his big-character poster on the Democracy Wall. Entitled "The Fifth Modernization", it complained that after the Cultural Revolution, the status quo remained unchallenged. The only democracy acknowledged was "democracy under collective leadership", which was only lip service when people were not actually allowed to make their own decisions.[136] Strongly critical of Mao, Wei called him the "self-exalting autocrat" who led China to the wrong road. He also criticized Deng's regime, under which "the hated old political system has not changed, and even any talk about the much hoped for democracy and freedom is forbidden." He defined true democracy as "the holding of power by the laboring masses" and deemed it a necessary pre-condition for successful modernization. Anyone who refused to grant this democracy was "a shameless bandit no better than a capitalist who robs workers of their money earned with their sweat and blood." He called for action: "Let me call on our comrades: Rally under the banner of democracy and do not trust the autocrats' talk about 'stability and unity.'...Democracy is our only hope. Abandon our democratic rights and we will be shackled once again. Let us believe in our own strength!"

Wei Jingsheng was not immediately arrested for putting up this poster, but Deng Xiaoping grew increasingly impatient about such attacks on his policies and the party, which he complained about during the Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Communist Party.[137] Deng was wary that this call for democracy would push the country too rashly for radical liberalization that may return the society to the same chaos as the Cultural Revolution.[137] He accused "the democracy activists" for holding on to past problems and colluding with foreign forces.[138] On March 16, 1979, Deng announced the "Four Cardinal Principles," namely the principle of upholding the socialist path, the people's democratic dictatorship, the leadership of CCP, and Mao Zedong Thought and Marxism–Leninism. Without explicit statement, this announcement essentially curtailed people's right to openly criticize the regime.

In response, Wei Jingsheng put up another big-character poster on March 25, 1979, titled "Do we want democracy or a new dictatorship," in which he explicitly criticized Deng Xiaoping.[139] He described Deng as a "true headsman" for suppressing the mass movement and repudiating the democracy movement. This time, he was arrested in four days and taken custody by the Beijing Public Security Bureau. He was brought to trial on October 16, 1979, convicted of being a "counter-revolutionary" and selling "state secrets to foreigners", and was sentenced to fifteen years imprisonment.[140]

The end of big-character poster as a legitimate form of political writing

editDeng Xiaoping moved on to impose more restrictive statutes and ordinances on big-character posters. The Beijing Municipal Revolutionary Committee passed an ordinance on April 6, 1976, stating that the posting of big-character posters on streets, public forums, and buildings was prohibited "except in designed places."[141] Similar ordinances were subsequently passed in all of China's provincial capitals by April 1979.[140] On July 1, 1979, the National People's Congress passed the Criminal Law. In addition to criminalizing "counter-revolutionary acts" that attempt to overthrow the socialist system in general, it specifically targets big-character posters. Article 145 reads: "Whoever, by violence or other methods, including the use of big-character posters . . . publicly insults others or fabricates facts to libel them, if the circumstances are serious, shall be sentenced to fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years, criminal detention, or deprivation of political rights."[142] On November 29, 1979, the National People's Congress passed another resolution restricting big-character posters, this time targeting the Xidan Democracy Wall. It defined the Democracy Wall as being "used by people who have the secret motive to violate the law, disrupt social order, and hinder the smooth implementation of the Four Modernizations."[143] On December 6, 1979, the Beijing Municipal Revolutionary Committee passed an ordinance, prohibiting the posting of big-character posters at Xidan Democracy Wall (and all places other than the designated site in Yuetan Park). It also required all writers to register their real name, address, and work unit.[144] On September 10, 1980, the National People's Congress passed another resolution, which deleted the right to put up big-character posters, along with the other Great Freedoms, from the Constitution, in the name of "[giving] full scope to socialist democracy, [improving] the socialist legal system, [maintaining] political stability and unity, and [ensuring] the smooth progress of the socialist modernization program."[145]

Despite such restrictions, big-character posters were still posted in the 1980s, mostly by students. In 1980, in Changsha, during the election for the local people's congress, many big-character posters questioned the candidates' qualifications.[146] In December 1986, students in Beijing and other major cities posted big-character posters, in which they demanded democratic reforms and even an end to the one-party system.[147] Two posters supporting the concurrent student demonstration went up in Peking University yet was quickly torn down.[148] On December 19, 1986, students in Shanghai Jiaotong University also put up big-character posters when Jiang Zemin, then Head of the Shanghai Communist Party, discouraged students from holding demonstrations.[149] The official media also condemned the students. People's Daily stated that big-character posters, which created huge chaos during the Cultural Revolution, were "loathed and opposed by the overwhelming majority of Chinese."[150] Beijing Daily pointed out that big-character posters were not protected by law and urged citizens to remove every big-character poster they encountered.[151] Students burned copies of Beijing Daily and People's Daily in protest.[152]

In 1988, students used big-character posters to complain about the educational environment and student conditions.[153] In 1989, before the 1989 Tiananmen Square Protest, big-character posters spread from university campuses to Tiananmen Square.[154] People's Daily again criticized these posters for "defaming, insulting, and attacking the leaders of the Party and the State."[155]

Finally, on January 20, 1990, the State Education Commission banned the use of big-character posters on university campuses.[149]

Legacy

editAs a form of political expression, big-character posters continue to be used and appropriated. In 2018, as part of the #MeToo movement, students at Peking University used big-character posters to denounce the school administrators' handling of a sexual harassment case.[156] In more recent times, these have been replaced with "Heng Fu" (横幅, lit. 'horizontal scroll') with "Biao Yu" (标语, an inspirational or motivational message or an announcement) inscribed on them.[157] These long, red-colored banners with white or yellow Chinese characters are found all over China in residential complexes as well as in universities and schools.[158][159]

Big-character posters have featured prominently in contemporary Chinese art. Many contemporary artists work with Chinese characters, and Wu Shanzhuan and Gu Wenda in particular have appropriated the aesthetics of big-character posters. In Red Humor (1986), Wu Shanzhuan covered an entire room with sheets of paper written with big characters. Instead of political dissent, the papers are filled with random words, trivial announcements, and disjointed quotations.[160] The work generates an overwhelming visuality similar to the one created by actual big-character posters during the Cultural Revolution.

Content

editDuring the Cultural Revolution, when the writing of big-character posters peaked, most big-character posters shared the same rhetorical formula, as they all emulated the first poster written by Nie Yuanzi et al.[161] Big-character posters were also copied and reprinted, which further standardized its structure.[162]

Beginning

editA big-character poster usually begins with praising Mao and the current regime and confirming the success and legitimacy of the Cultural Revolution.[163] Nearly every poster included a quotation from Mao in the beginning, which served to introduce the general moral principles as the basis for the subsequent accusations. It provided a political camouflage for the following content which might have nothing to do with politics yet attempt to resolve personal resentment.[164] It also helped propagate Mao's ideas and ethos.[165] One of the most commonly used quotes was "Revolution is no crime, to rebel is justified."[166]

Identify the target

editA poster would proceed to present the name of the accused and their crimes. Most big-character posters attacked people by their names. Occasionally, to humiliate a target, one's name would be intentionally written upside down or replaced with a homophone character with a strong negative connotation.[167] When describing class enemies, the writer often used animal metaphors to further demean them. The most common ones include niugui sheshen (ox demons and snake spirits), gouzaizi (sons of dogs/bastards of minions), yaomo guiguai (monsters and demons, ghosts, and goblins), xiao pachong (small reptiles), zougou (walking dogs/minions), simao langou (dead cats and rotten dogs).[168] These labels dehumanized class enemies and justified the subsequent condemnation and violent actions.[169] Most targets belonged to the five black categories (landlords, rich farmers, counter-revolutionaries, bad elements, rightists). However, these categories, especially the latter three, were only loosely defined, enabling them to target a wider range of people.[168]

It was common for one to denounce one's family members, friends, and close colleagues through big-character posters to prove one's loyalty to Mao Zedong and CCP and to save themselves.[170] Such practices were widely encouraged, as these writers would be able to expose the "true character" of the target. For instance, in 1967, instigated by Jiang Qing, Liu Tao and Liu Yunzhen put up a big-character poster against their father Liu Shaoqi.[171] People also chose to criticize themselves with big-character posters.[172]

Big-character posters against state officials were closely monitored and supervised by the Party Central Committee. For instance, in 1971, it was determined that while the proletariat could discuss the Lin Biao matter amongst themselves, no big-character posters shall be posted.[173]

Justify the accusation

editTo justify their accusations, the writer might use a variety of evidence. Any habit and behavior could be framed as being feudalist, capitalist, bourgeoise, or revisionist, and a small fault was all that was needed to repudiate the target.[174] Arranging a high-standard funeral for one's mother could be considered feudalist.[175] Having any personal property or living one's life slightly above average would be considered a violation of egalitarianism and criticized as bourgeoise.[176] A female student in the Department of Mechanics of Tsinghua University accused the university president as revisionist for treating female students too leniently during their menstrual periods.[177]

Each word was chosen with intention. By replacing neutral terms with words with negative implications, for instance substituting "sneaking" for "joining", "heresy" for "a different perspective", the writer could defame one's target more effectively. In addition, a big-character poster may trace a target's past behavior and actions and look for things that could be retrospectively criticized.[178] Even when people had been struggled and had allegedly reformed themselves in the past, they may still be dragged out and forced to go through another round of humiliation and criticism, such as old Republican generals Du Yuming and Song Xilian.[179]

If the accused had said or written something problematic, the accuser would often include a phrase-by-phrase rejection of their arguments.[161] When no fault could be found in one's actions, the accuser may question a target's possible motives, which often entailed exaggeration, distortion, and fabrication.[180] One could also be labeled counter-revolutionary simply by one's family background.[181]

In previous campaigns, one's sexual relations remained off-limit for discussion in big-character posters.[182] Peng Zhen emphasized in 1963 that though big-character posters were effective, "No big-character posters should be put up dealing with topics such as an individual's...private life."[183] However, during the Cultural Revolution, "illicit sexual liaisons", "moral depravity", and other decadent behaviors were deemed fair game since decadent lifestyle was a main feature of the bourgeoise.[184] Such accusations, though only presented as a complement to more serious allegations,[185] were extremely effective in defiling one's reputation. According to Wang Zhongfang, "if you wanted to overthrow and really disgrace someone, the preferred way of going about it was to raise the subject of sexual relations....In the end that person might be too ashamed to face anyone, and might even attempt suicide."[186]

While different targets may be accused of different mistakes, every questionable behavior would be connected to larger anti-party or anti-Mao crimes, such as being an "unrepentant capitalist roader" to a "hidden spy and traitor," a "counterrevolutionary," a "conspirator and plotter," a "revisionist", etc.[187]

Against the enemy

editOnce a big-character poster succeeded in presenting the accused as guilty, it went on to call for a violent struggle against the target. The writer often vowed to "smash the enemies into pieces", "step one thousand feet on their bodies and never let them get back up again in their life time."[188] A Beijing Red Guard in 1967 wrote that Deng Xiaoping "really should be cut into pieces by thousands of knives, burned in fire and fried in oils."[189] The Red Guards would describe themselves as "fighters protecting Mao, wielding their pens like knives and rifles."[190] In 1967, Beijing factory workers promised that they would condense all their hatred into "the most concentrated bullets and the hottest flame, shoot them towards the anti-revolutionary revisionist clique led by Peng Zhen and supported by Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping, and burn them into ashes."[191] They were perhaps inspired by Mao himself, who in 1957 already described big-character poster as "small arms such as rifle, pistol and machine gun."[192] Such violent words often translated to real violence. Once accused in a big-character poster, a person would also suffer house searches and even robberies.[176] Some students from a Tianjin middle school physically nailed a big-character poster to their teacher's back.[193]

Cursing words such as hundan (bastard) and tamade (damn you) were commonly used to agitate the readers. Superlatives and exclamation marks also enhanced the emotional charge.[163] For instance, Mao was often described as "the reddest and reddest sun in our heart."[194] The enemies were usually denounced as "the most hidden peril", "the worst potential plague", and "the most heinous counterrevolutionary and revisionist."[195]

Ending

editA big-character poster ended with slogans eulogizing Mao, pledging the writer's unconditional loyalty and support, and reinstating their hatred against class enemies.[196] For instance, a Red Guard group pledged to "fight till their death to defend Chairman Mao and the proletarian headquarters."[197]

While Nie Yuanzi et al. signed their poster with their real names, most writers would only sign the name of their institution, department, Red Guard group, or revolutionary unit.[198] They may also sign with a pseudonym with revolutionary implications, such as "Loyalty Red Courage" or "revolutionary masses."[167] Without a proper signature, the authors did not have to take any responsibility for what they wrote.[162]

Function

editBig-character posters became a crucial tool in Mao's struggle during the Cultural Revolution. Mao intended to use big-character posters to expose and accuse his political enemies and to agitate class struggle against them, and the posters effectively accomplished this goal. Infiltrating people's public and private life (they can even be posted in dormitories), these posters left no respite for the accused and demanded their immediate reaction, as being attacked in a big-character poster was enough to end one's career.[199]

The posters had a much wider range of applications. These ubiquitous were used for everything from sophisticated debate to satirical entertainment to rabid denunciation; Big-character posters were informative. When most ordinary newspapers and publishing houses were halted by the struggle, posters provided the most updated news, change in policies, and even gossips.[200] Many people read big-character posters, which were filled with scandals, rumors, and spy stories, as "real-time drama."[201]

Big-character posters also created an accessible public forum which was to a large extent democratic. As they were written anonymously and could be secretly put up in prominent places for public appreciation, big-character posters bypassed top-down censorship and control imposed on other forms of public writing.[202] Compared to the closed-off and secretive party propaganda system, the free and largely spontaneous writing, posting, reading, and copying of big-character posters created a much more open network that worked independently from the official channels.[176] In addition, big-character posters opened the once infallible government and high-ranking officials to public scrutiny and criticism.[203] Moreover, public discourse was no longer monopolized by intellectual elites since every literate citizen could use this form to express their political dissent.[162]

However, once Mao Zedong identified the writing and reading of big-character posters as a revolutionary activity, it became mandatory. If someone dared to not care about big-character posters, chances are that they would become the next target for their lack of interest.[176] Many people, including writer Yu Hua, wrote big-character posters as a way to perform repentance for incorrect past tendencies and demonstrate their renewed commitment to the revolutionary course.[204]

Big-character posters could be used to achieve all kinds of goals. In high-level political struggles, big-character posters could not only be used to bring down one's opponent but also to support one's ally. In late 1967 and early 1968, after the February Countercurrent, Lin Biao and other members of the Cultural Revolution Small Group attempted to bring down Chen Yi, Foreign Minister of China. Those who supported Chen did not write big-character posters directly in his defense but chose to expose problems of those who wanted to take him down and frame them as anti-party and anti-Mao.[101] Since the Hundred Flowers Campaign, big-character posters were considered an effective tool to encourage mass participation in factory management.[205] Workers would write posters anonymously to criticize the managers, expose problems and contradictions, and offer suggestions. One such poster complained that the good ration was too small and criticized the factory manager for being "passive and muddleheaded."[206]

Many scholars have argued that big-character posters have far-reaching influences, as the experience of reading and writing big-character posters was impressed on the memory of many generations of Chinese people. Political scientist and sinologist Lucian Pye believes that their emphasis on confrontation, hatred, and rebelliousness had a significant impact on the socialization of a generation of Chinese children who have become adults.[207] Lu Xing argues that as most big-character posters convey a belief in moral absoluteness and unconditional acceptance of the dominant ideology, they deprived the Chinese the ability to think critically.[208] In addition, to enhance their emotional appeal, big-character posters would often repeat extreme phrases, which limited people's linguistic options and imaginations.[208]

The style of big-character poster

editBig-character posters are generally 3 feet by 8 feet, and each character was usually 3 inches by 4 inches. Most were handwritten on white or red backgrounds with black or red ink.[56] Contrary to contemporary propaganda posters which were mass-produced, every big-character poster was written by a unique hand, though the content might be republished in magazines and journals or broadcast on radio. Handwriting not only gives the poster a visceral power and a heightened sense of immediacy, but it also relates big-character poster to the revered art of calligraphy, practiced by none other than Mao Zedong.[209] Many people imitated Mao's calligraphy, which would be written at the top of their posters.[210]

Big-character posters as material objects

editBig-character poster was a product of modernity, as mass consumption of paper was only possible after the technical development in the production of paper in the modern era.[211] During the Cultural Revolution, the writing of big-character posters could use up to 300,000 large pieces of paper each month, which was more than three times the regular monthly consumption; the glue for pasting big-character posters also cost more than 1100 pounds of flour every day.[212] When excessive writing resulted in an occasional shortage of supply,[213] people used old newspaper, scratch paper, mud, and even horse dung.[214] When wall space ran out, people would hang their posters on ropes or strings.[214] During the Hundred Flowers Campaign, people also created temporary walls by attaching woven mats to wooden frames to put up their big-character posters.[215]

Big-character posters were not meant to be permanent. The Central Committee may order certain posters to be covered up or town down, and posters were also frequently torn down by opposing factions, filling the streets with shredded paper.[114] Some Beijing residents could even live off selling wastepaper.[216] In the summer of 1968, it was reported that children would tear down big-character posters and sell the paper for pulp.[217]

Gender in big-character posters

editIn the Cultural Revolution, inspired by the rhetoric of absolute egalitarianism, young women, vowing to do whatever a man can do, were eager to project an image of themselves as tough, fearless, and enduring by denying any form of gendered physical weakness.[218] These female students were often more aggressive and radical than their male counterparts. They often used more cursing, which was seen as a symbol of masculinity and toughness, to demonstrate their revolutionary spirit.[219]

On June 18, 1966, during a public criticism in Peking University, a male student in the Department of Wireless Communications sexually assaulted a female cadre and two female students and was subsequently punished.[220] In a big-character poster, a female student attempted to justify the crime as a demonstration of class hatred and an act of revolution and acclaimed: "Let's have some more!"[221]

Big-character posters in other countries

editIn Albania

editBig-character posters appeared also in Albania as a result of Albania's Cultural Revolution, imported from China in 1967 in communist Albania. Called fletërrufe in the Albanian language, it was used by the Party of Labor of Albania to both spread communist ideas, as well as to publicly denounce and humiliate possible deviators from the Party's line.[222][223]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c Lu, Xing (2020). Rhetoric of the Chinese Cultural Revolution: The Impact on Chinese Thought, Culture, and Communication. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. p. 74.

- ^ Li, Henry Siling (2009). "The Turn to the Self: From 'Big Character Posters' to YouTube Videos1" (PDF). Chinese Journal of Communication. 2 (1): 51. doi:10.1080/17544750802639077. S2CID 145231019.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies Copenhagen. p. 32.

- ^ Couper, John Lord; Cui, Litang (2018). "Big Changes, Big Characters: Public Development Discourse in Yunnan, China". Jurnal studi komunikasi. 2 (2): 233.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 38.

- ^ Harrison, Henrietta (2000). The Making of the Republican Citizen : Political Ceremonies and Symbols in China, 1911-1929. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 142.

- ^ Wasserstrom, Jeffrey N. (1991). Student Protests in Twentieth-Century China : the View from Shanghai Stanford. California: Stanford University Press. pp. 124–126.

- ^ Zhang, Shaoqian (2016). "Visualizing the Modern Chinese Party-State: From Political Education to Propaganda Agitation in the Early Republican Period". Twentieth-century China. 41 (1): 65. doi:10.1353/tcc.2016.0003. S2CID 146987421.

- ^ Zhang, Shaoqian (2016). "Visualizing the Modern Chinese Party-State: From Political Education to Propaganda Agitation in the Early Republican Period". Twentieth-century China. 41 (1): 63.

- ^ Markham, James W. (1967). Voices of the Red Giants. Iowa State University Press. p. 375.

- ^ Poon, David Jim-tat Poon (1978). "Tatzepao: Its History and Significance as Communication Medium". In Chu, Godwin C. (ed.). Popular Media in China: Shaping New Cultural Patterns. Honolulu: East-West Center, University of Hawaii. pp. 184–221.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 42.

- ^ a b Hua, Sheng (1990). "Big Character Posters in China: A Historical Survey". Journal of Chinese Law. 4 (2): 235.

- ^ Hua, Sheng (1990). "Big Character Posters in China: A Historical Survey". Journal of Chinese Law. 4 (2): 236.

- ^ Mao, Zedong; Minoru, Takeuchi (1986). Mao Zedong ji bu juan. Bei juan : Mao Zedong zhu zuo nian biao = Supplements to Collected writings of Mao Zedong Shohan (in Chinese). Tokyo: Sōsōshe. p. 287.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "在最高国务会议上的讲话". Marxist.org. Archived from the original on 2018-07-17.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 2.

- ^ Knight, Nick (2007). Rethinking Mao : Explorations in Mao Zedong's Thought. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 224.

- ^ Wemheuer, Felix (2019). A Social History of Maoist China : Conflict and Change, 1949-1976. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 112.

- ^ Wemheuer, Felix (2019). A Social History of Maoist China : Conflict and Change, 1949-1976. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. p. 113.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 8.

- ^ Mao, Zedong. "THINGS ARE BEGINNING TO CHANGE". Marxists Internet Archive. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ a b Liu, Guanghua (May 26, 1957). "北京大学民主墙" [The Democracy Wall in Peking University]. Wenhui Ribao (Wenhui Daily). p. 2.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 10-11.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰[Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 11-35.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 48.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰[Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 11.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 16-17, 19, 24-25.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 14-15.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 21.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 11.

- ^ Guangming Daily (May 26, 1957). Cited in Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 48.

- ^ Yang, Kuisong; Benton, Gregor; Zhen, Ye (2020). Eight Outcasts Social and Political Marginalization in China Under Mao. Oakland, California: University of California Press. pp. 60–61.

- ^ Knight, Nick (2007). Rethinking Mao : Explorations in Mao Zedong's Thought. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books. p. 225.

- ^ Wang, Tuo (2014). The Cultural Revolution and Overacting: Dynamics Between Politics and Performance. Lanham: Lexington Books. p. 43.

- ^ Li, Henry Siling (2009). "The Turn to the Self: From 'Big Character Posters' to YouTube Videos1". Chinese Journal of Communication. 2 (1): 52.

- ^ "文汇报在一个时间内的资产阶级方向" [Wenhui Daily's bourgeoise direction for a period of time]. 人民日报. June 14, 1957. p. 1.

- ^ "文汇报的资产阶级方向应当批判" [Wehui Daily's bourgeoise direction should be criticized]. 人民日报. July 1, 1957. p. 1.

- ^ Hua, Sheng (1990). "Big Character Posters in China: A Historical Survey". Journal of Chinese Law. 4 (2): 237.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 51.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "中央关于加紧进行整风的指示(一九五七年六月六日)" [Directions on speeding up the rectification campaign from the Central Committee (June 6, 1957)]. 建国以来毛泽东文稿 (PDF) (in Chinese). Vol. 6. p. 491.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "1957年夏季的形势" [The Situation in the Summer of 1957]. Marxists.org. Archived from the original on 2010-03-24.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 37.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 33.

- ^ Mao, Zedong (1967). "Be activists in promoting the revolution". Selected Readings from the Works of Mao Tsetung. Vol. 5. Beijing: Foreign Language publishing House. p. 484.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 49.

- ^ a b 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 51.

- ^ a b c Hua, Sheng (1990). "Big Character Posters in China: A Historical Survey". Journal of Chinese Law. 4 (2): 238.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 42.

- ^ Wenhui Bao (Wenhui Daily) (Sept. 28, 1957): 2.

- ^ Guangming Ribao (Guangming Daily) (Sept. 24, 1957): 1.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 56.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 44-45.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 56.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 55.

- ^ a b Heller, Steven (2008). Iron Fists : Branding the 20th-Century Totalitarian State. London: Phaidon. p. 195.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "介绍一个合作社(1958年4月15日)" [Introducing a cooperative (April 15, 1958)] (PDF). Marxists.org. p. 178. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-08-30.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 81-83.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 75-79.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 62-69.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 71-72.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 90-91.

- ^ Cited in 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 92-93.

- ^ "滚,滚,滚,美国军队从台湾滚出去!". 人民日报(People's Daily). September 8, 1958. p. 7.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 61.

- ^ Cited in 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 84.

- ^ Cited in 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 99.

- ^ a b 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 101.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 57.

- ^ a b Han, Dongping (2008). The unknown cultural revolution : life and change in a Chinese village. New York. p. 60. ISBN 978-1-58367-180-1. OCLC 227930948.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 中国共产党组织史资料 [Materials on Chinese Communist Party's Organization History] (in Chinese). 中共党史出版社. 2000. p. 168.

- ^ a b c d e f "The First "Big-Character Poster"". China's Cultural Revolution in Memories: The CR/10 Project. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 56.

- ^ 姚, 文元 (May 10, 1966). "评《三家村》" [On Three-Family Villages]. 解放日报 [Jiefang Daily]: 1, 3.

- ^ a b Nie Yuanzi, Song Yixiu, Xia Jianzhi, Yang Keming, Zhao Zhengyi, Gao Yunpeng, Li Xingchen (1966). "宋硕、陆平、彭珮云在文化革命中究竟干些什么?" [What are Song Shuo, Lu Ping, and Peng Peiyun up to in the Cultural Revolution]. In Highlights of Da-Zi-Bao during the Cultural Revolution (in Chinese). Flushing, NY: Mirror Books. pp. 22–24

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 54.

- ^ 北京大学文化革命委员会宣传组 (1966). 北京大学无产阶级文化大革命运动简介 [Brief Introduction to the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution at Peking University] (in Chinese). Beijing. p. 2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lin, Haoji (1989). "北大第一张大字报是怎样出笼的" [How the First Big-Character Poster Appeared at Peking University]. In Zhou, Ming (ed.). 历史在这里沉思 [Here History Is Lost in Thought] (in Chinese). Vol. 2. Beijing: 华夏出版社. p. 32.

- ^ Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 59.

- ^ a b 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 112.

- ^ 中共中央文献研究室 (1996). 刘少奇年谱,1898-1969 [Chronicle of the Life of Liu Shaoqi, 1898–1969] (in Chinese). Vol. 2. Beijing: Central Literature Publishing House. p. 640.

- ^ Wang, Nianyi (1988). 大动乱的年代 [A Decade of Great Upheaval] (in Chinese). Zhengzhou: 河南人民出版社. p. 29.

- ^ 河北北京师范学院斗争生活编辑部 (1967). 无产阶级文化大革命资料汇编 [Collected Documents from the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution] (in Chinese). Beijing. p. 667.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 中共中央文献研究室 (1997). 周恩来年谱, 1949-1976 [Chronicle of the Life of Zhou Enlai, 1949–1976] (in Chinese). Vol. 3. Beijing: Central Literature Publishing House. p. 32.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "关于发表全国第一张马列主义大字报的批示 (1966年6月1日)" [Directive on Publishing the first national Marxist-Leninist Big-Character Poster] (PDF). Marxists.org. p. 261. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-08.

- ^ Chen, Boda (June 2, 1966). "欢呼北大的一张大字报" [Hail Peking University's Big-Character Poster]. 人民日报(People's Daily) (in Chinese): 1.

- ^ a b Leijonhufvud, Göran (1989). Going Against the Tide: On Dissent and Big Character Posters in China. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 60.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 118.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 67.

- ^ 革命造反总部真理战斗队 (1967). 邮电部机关文化大革命运动史料 [Materials on the History of the Great Cultural Revolu- tion Movement in the Organs of the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications] (in Chinese). Beijing. p. 3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 118-126.

- ^ "We just thought that this seemed to be part of the revolution, copying 'big-character posters'..." China's Cultural Revolution in Memories: The CR/10 Project. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09.

- ^ Ji, Xianlin (1998). 牛棚杂忆 [Scattered Memories from Cow Shed] (in Chinese). 中共中央党校出版社. p. 17.

- ^ "彻底肃清前北京市委修正主义路线的毒害". 人民日报(People's Daily). June 21, 1966. p. 2.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 72.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 129-130.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "重要讲话(1966年7月21日)" [Important Speech (July 21, 1966)] (PDF). Marxists.org (in Chinese). p. 263.

- ^ 毛, 泽东. "在会见大区书记和中央文革小组成员的讲话(1966年7月22日)" [Speech when meeting regional secretaries and members of the Cultural Revolution Small Group (July 22, 1966)] (PDF). Marxists.org. p. 264. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-08.

- ^ MacFarquhar, Roderick; Schoenhals, Michael (2006). Mao's Last Revolution. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 84.

- ^ a b 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 151.

- ^ 罗, 平汉 (2001). 墙上春秋:大字报的兴衰 [Springs and Autumns on the Wall: The Rise and Fall of Big-character Posters] (in Chinese). 福建: 福建人民出版社. p. 151-152.