Bawana Fortress or Bawana Zail, also Bawana Jail and Bawana tehsil is a historic fortress at Bawana in Delhi in India, it was built in 1860s by Jat chaudhary (chiefs) of the area who became zaildar of Bawana zail during the British raj.[1][2]

| Bawana Fortress Bawana Tehsil | |

|---|---|

| Bawana Zail Bawana Jail | |

Bawana Fortress in Delhi | |

| Etymology | From Hindi word "bawan" (52) |

| Location | Bawana |

| Nearest city | Sonepat |

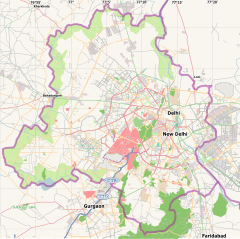

| Coordinates | 28°48′N 77°02′E / 28.8°N 77.03°E |

| Built | 1860s CE |

| Built for | Jat chaudharies |

| Original use | Fortress and jail |

| Restored | 2017 |

| Restored by | Delhi state Archaeology dept |

| Architectural style(s) | Lakhouri bricks |

| Owner | Government of Delhi |

History

editBawana (बवाना), established in 1168,[1] was previously called Bawani (बावनी).[3] It received this name from the Hindi language word "bawan" (52) since this area was a grouping of 52 villages, 17 in Narela, 17 in Karala, 6 in Palam and 12 directly under Bawana, with 5,200 bighas of agricultural land.[3][1] Revenue department records mention two people connected with its origins, "Kala" and "Thakur" who came from Bengal.[3] The Jat people of Taoru, who initially migrated to Mehrauli, settled at Bawana after spending significant time there. In due time they became influential enough to become chaudhary (chief) of the area. In the 1860s, Bawana became a Zail (revenue unit) with 3 other villages, Bawana, Alipur and Kanjhawala, under its authority when the British introduced the colonial zaildari revenue collection system in 1860s. Jat chief, who was the Zaildar of Bawana Zail, built the Bawana Fortress in the 1860s as the headquarters of Bawana Zail. Along with Zails of Mehrauli, Dilli, and Najafgarh, Bawana was one of the four Zails within the colonial era Delhi district.[1][2][4][5][6][7] Additional zails of Badarpur, Badli, Nangloi, Palam Zail and Shahdara Zail might have come up later.[8]

In the 1930s-40s, authorities started to use Bawana Zail Fortress as a school. Later it, also served as a veterinary hospital for a short time before being used as an orphanage. During the 1996-98 rule of Jat Chief Minister of Delhi Sahib Singh Verma, it was turned into an office of Patwari, hence the zail fortress also came to be known as "Bawana Tehsil". Eventually, this run-down building was abandoned.[1][2]

"From the zails of Bawana, Kanjhaola, and Alipur, 1,231 men went to the great war (first World War, 1914-1919). Of these, 81 gave up their lives."

Architecture

editIt is a 200 square yard single story structure of ramparts and parapets built with lakhori bricks and lime mortar. It has a grand arched gateway that opens into an inner courtyard surrounded by corridors. In the courtyard, the extreme corner on the left has two rooms that were used as jail by the Jat zaildar to imprison those zamidars who defaulted on their zamindari land tax. Next to the jail rooms, a small staircase leads to the terrace. The terrace has one bastion on each of its four corners. These bastions served as guard posts. The courtyard had a water well to serve the occupants.[1][2]

Conservation

editAfter the Bawana fortress was abandoned around late 1990s or so, large portions of its walls, built from lakhori bricks, were ruined from both the out- and inside. The parapet collapsed. The old water well dried up and its water also turned saline. It saw minor restorations in 2004 and again in 2010 for the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi, though the earlier 2004 plan to convert it into a monument for the Indian independence freedom fighters did not materialise. In February 2017 major restoration by the State Archeology department of the Government of Delhi eventually commenced, using original construction material of that era, including a concrete preparation with 23 ingredients including lime, surki (trass), jaggery, bael fruit (wood apple) pulp and urad ki daal (paste of vigna mungo pulse).[1][2]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h Bawana’s 19th-century fortress gets a makeover Hindustan Times, 20 Feb 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Bawana jail being restored, Hindustan Times, 2017.

- ^ a b c Delhi traces its lost rural roots, Times of India, 9 Jan 2011.

- ^ Rajesh K. Agarwal, 1974, Economic and Employment Potential of Archaeological Monuments in India, Sudesh Nangia, Birla Institute of Scientific Research, Economic Research Division.

- ^ 1954, Gazette of India, Page 320.

- ^ 1921, Annual Progress Report of the Superintendent, Muhammadan and British Monuments, Northern Circle, Archaeological Survey of India, Northern Circle.

- ^ 1937, Administration Report, Page 21.

- ^ Susan Sinclair, 2012, Bibliography of Art and Architecture in the Islamic World (2 vol. set), p85.