Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans (Bsal) is a pathogenic chytrid fungus that infects amphibian species. Although salamanders and newts seem to be the most susceptible, some anuran species are also affected. Bsal has emerged recently and poses a major threat to species in Europe and North America.

| Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans | |

|---|---|

| |

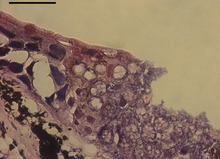

| Bsal infection in the skin of a fire salamander | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Chytridiomycota |

| Class: | Chytridiomycetes |

| Order: | Rhizophydiales |

| Family: | Batrachochytriaceae |

| Genus: | Batrachochytrium |

| Species: | B. salamandrivorans

|

| Binomial name | |

| Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans Martel A., Blooi M., Bossuyt F., Pasmans F. (2013)[1]

| |

It was described in 2013 based on a strain collected from skin tissue of fire salamanders Salamandra salamandra. The pathogen, unidentified up to then, had devastated fire salamander populations in the Netherlands. Molecular phylogenetics confirmed it as related to the well known chytrid B. dendrobatidis. Like this species, it causes chytridiomycosis, which is manifested in skin lesions and is lethal for the salamanders.[1] Damage to the epidermal layer can be extensive and may result in osmoregulatory[2] issues or sepsis.[3]

Another study estimated that this species had diverged from B. dendrobatidis in the Late Cretaceous or early Paleogene. While initial susceptibility testing showed frogs and caecilians seemed to be resistant to Bsal infection, it was lethal to many European and some North American salamanders. East Asian salamanders were susceptible but able to tolerate infections. The fungus was also detected in a more-than-150-year-old museum specimen of the Japanese sword-tailed newt. This suggests it had originally emerged and co-evolved with salamanders in East Asia, forming its natural reservoir, and was introduced to Europe rather recently through the trade of species such as the fire belly newts as pets.[4] The asian origin hypothesis for Bsal is supported by additional studies which have found Bsal in wild urodela populations in Asia and in animals of asian origin being transported via the pet trade.[5][6][7] Since the pathogens initial discovery, it has been found in several additional areas across Europe in both wild and captive populations. One study was able to detect Bsal in 7 of 11 captive urodele collections.[8]

The description of this pathogen and its aggressiveness raised concern in the scientific community and the public, fearing that it might be a rising threat to Western hemisphere salamanders.[9][10] On January 12, 2016, the U.S. government issued a directive that prohibited the importation of salamanders in order to reduce the threat posed by B. salamandrivorans.[11]

Etymology

editBatrachochytrium is derived from the Greek words batrachos, "frog", and chytra, "earthen pot" (describing the structure that contains unreleased zoospores); salamandrivorans is from the Greek salamandra, "salamander", and Latin vorans, "eating", which refers to extensive skin destruction and rapid death in infected salamanders.[12]

Distribution

editBsal appears to occupy a narrow climactic niche in its native range in East and Southeast Asia.[13] In its introduced range in Europe, it was first detected in the Netherlands in 2012, where it wiped out a majority of the country's small fire salamander population. It has since naturally expanded into Belgium, western Germany, and possibly Luxembourg, although it was likely present in some of these regions well before the documented outbreaks; the oldest known record is from Germany in 2004, for example.[14][15] In Germany, it is primarily known from the states of North Rhine-Westphalia and Rhineland-Palatinate, with the core of its range being in the Eifel Mountains, where it has caused landscape-scale declines of fire salamanders.[16] It was detected in the state of Hesse in 2024, on the border with North Rhine-Westphalia, where it was found to have caused a mass mortality of fire salamanders.[17]

In addition to this contiguous range, several isolated outbreaks have been reported. One such outbreak is known from the Steigerwald in Bavaria, Germany, which was possibly introduced either by hitchhiking on shoes, animals, or machinery, although it is also possible that it had naturally expanded from northern Germany unnoticed.[18] The southernmost outbreak was identified in Allgäu in 2020, which was possibly associated with an accidental introduction via aquatic plants for garden ponds; this outbreak caused a mass mortality event among alpine newts. Due to its proximity to the Alps, this outbreak poses a major risk to the alpine salamander and Lanza's alpine salamander if allowed to expand.[19][20] Another outbreak was identified in a single site in Catalonia, Spain in 2018, which likely originated from released captive individuals. This outbreak caused mortality in fire salamanders and marbled newts, and posed a severe threat to the endemic salamanders of the Iberian Peninsula; the site was thus impounded to contain the outbreak and prevent any spillover. Several other reports of Bsal from other parts of Spain are thought to be false positives, as later surveys of these sites have found no presence of the disease.[21]

Susceptible species

editThe most comprehensive Bsal species susceptibility performed to date has been by Martel et al 2014.[4] Their experiments demonstrated Bsal susceptibility followed a phylogenetic trend with many Salamandridae species being lethally susceptible. Recent work has demonstrated that some lungless species, specifically those in the Spelerpini tribe might also be clinically susceptible to Bsal [22]

Threats to salamanders

editBsal is a serious threat to salamander species, while it has not yet been confirmed in North America,[23] Bsal has had catastrophic effects on certain European salamander populations, believed to be the cause of a 96% decline in populations with in the Netherlands.[24] More than a third of the worlds salamanders live in the United States,[25] and 40% of those salamanders are already threatened.[26] While regulations on the most likely avenue of introduction into North America, amphibian trade,[27] are in place in both Canada and the United States, regulations are seriously lacking in Mexico. Furthermore, Bsal has the potential to infect an estimated 80 to 140 North American salamander species.[28]

Tolerant

editThis section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2024) |

Susceptible

editThis section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2024) |

Lethal

editThis section includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (January 2024) |

- Hydromantes strinatii

- Salamandrina perspicillata

- Salamandra salamandra

- Pleurodeles waltl

- Tylototriton wenxianensis

- Notophthalmus viridescens

- Taricha granulosa

- Euproctus platycephalus

- Lissotriton italicus

- Ichthyosaura alpestris

- Triturus cristatus

- Neurergus crocatus

- Eurycea wilderae

- Pseudotriton ruber

Information sources

editMore information on Bsal and other diseases impacting amphibian populations, including Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Ranavirus can be found at the Southeast Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation disease task team web-page. [1]

References

edit- ^ a b c Martel, A.; Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A.; Blooi, M.; Bert, W.; Ducatelle, R.; Fisher, M. C.; Woeltjes, A.; Bosman, W.; Chiers, K.; Bossuyt, F.; Pasmans, F. (2013). "Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans sp. nov. causes lethal chytridiomycosis in amphibians". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 110 (38): 15325–15329. Bibcode:2013PNAS..11015325M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1307356110. PMC 3780879. PMID 24003137.

- ^ Voyles, J.; Young, S.; Berger, L.; Campbell, C.; Voyles, W. F.; Dinudom, A.; Cook, D.; Webb, R.; Alford, R. A.; Skerratt, L. F.; Speare, R. (2009). "Pathogenesis of Chytridiomycosis, a Cause of Catastrophic Amphibian Declines". Science. 326 (5952): 582–585. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..582V. doi:10.1126/science.1176765. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19900897. S2CID 52850132.

- ^ Bletz, Molly C.; Kelly, Moira; Sabino-Pinto, Joana; Bales, Emma; Van Praet, Sarah; Bert, Wim; Boyen, Filip; Vences, Miguel; Steinfartz, Sebastian; Pasmans, Frank; Martel, An (2018). "Disruption of skin microbiota contributes to salamander disease". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 285 (1885): 20180758. doi:10.1098/rspb.2018.0758. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 6125908. PMID 30135150.

- ^ a b c d e Martel, A.; Blooi, M.; Adriaensen, C.; Van Rooij, P.; Beukema, W.; Fisher, M. C.; Farrer, R. A.; Schmidt, B. R.; Tobler, U.; Goka, K.; Lips, K. R.; Muletz, C.; Zamudio, K. R.; Bosch, J.; Lotters, S.; Wombwell, E.; Garner, T. W. J.; Cunningham, A. A.; Spitzen-van der Sluijs, A.; Salvidio, S.; Ducatelle, R.; Nishikawa, K.; Nguyen, T. T.; Kolby, J. E.; Van Bocxlaer, I.; Bossuyt, F.; Pasmans, F. (2014). "Recent introduction of a chytrid fungus endangers Western Palearctic salamanders". Science. 346 (6209): 630–631. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..630M. doi:10.1126/science.1258268. PMC 5769814. PMID 25359973.

- ^ Cunningham, A. A.; Beckmann, K.; Perkins, M.; Fitzpatrick, L.; Cromie, R.; Redbond, J.; O'Brien, M. F.; Ghosh, P.; Shelton, J.; Fisher, M. C. (2015). "Emerging disease in UK amphibians". Veterinary Record. 176 (18): 468. doi:10.1136/vr.h2264. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 25934745. S2CID 26161581.

- ^ Laking, Alexandra E.; Ngo, Hai Ngoc; Pasmans, Frank; Martel, An; Nguyen, Tao Thien (2017). "Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans is the predominant chytrid fungus in Vietnamese salamanders". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 44443. Bibcode:2017NatSR...744443L. doi:10.1038/srep44443. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5347381. PMID 28287614.

- ^ Nguyen, Tao Thien; Nguyen, Thinh Van; Ziegler, Thomas; Pasmans, Frank; Martel, An (2017). "Trade in wild anurans vectors the urodelan pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans into Europe". Amphibia-Reptilia. 38 (4): 554–556. doi:10.1163/15685381-00003125. hdl:1854/LU-8625943. ISSN 0173-5373.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Liam D.; Pasmans, Frank; Martel, An; Cunningham, Andrew A. (2018). "Epidemiological tracing of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans identifies widespread infection and associated mortalities in private amphibian collections" (PDF). Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 13845. Bibcode:2018NatSR...813845F. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-31800-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6138723. PMID 30218076.

- ^ Stokstad, E. (2014). "The coming salamander plague". Science. 346 (6209): 530–531. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..530S. doi:10.1126/science.346.6209.530. PMID 25359941.

- ^ Rhodi, Lee (2014-10-31). "Skin-eating fungus Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans threatens to wipe out salamanders worldwide". Tech Times. Retrieved 2015-06-05.

- ^ "Listing Salamanders as Injurious Due to Risk of Salamander Chytrid Fungus". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. January 12, 2016.

- ^ "Etymologia: Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans". citing public domain text from the CDC. Emerg Infect Dis. 22 (7): 1282. July 2016. doi:10.3201/eid2207.ET2207. PMC 4918143.

- ^ Sun, Dan; Ellepola, Gajaba; Herath, Jayampathi; Meegaskumbura, Madhava (2023). "Ecological Barriers for an Amphibian Pathogen: A Narrow Ecological Niche for Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in an Asian Chytrid Hotspot". Journal of Fungi. 9 (9): 911. doi:10.3390/jof9090911. ISSN 2309-608X. PMC 10532633. PMID 37755019.

- ^ Porco, David; Purnomo, Chanistya Ayu; Glesener, Liza; Proess, Roland; Lippert, Stéphanie; Jans, Kevin; Colling, Guy; Schneider, Simone; Stassen, Raf; Frantz, Alain C. (2024). "eDNA-based monitoring of Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans with ddPCR in Luxembourg ponds: taking signals below the Limit of Detection (LOD) into account". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 24 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12862-023-02189-9. ISSN 2730-7182. PMC 10768104. PMID 38178008.

- ^ Lötters (2020). "The amphibian pathogen Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in the hotspot of its European invasive range: past – present – future" (PDF). Salamandra. 56 (3): 173–188.

- ^ Bolte, Leonard; Goudarzi, Forough; Klenke, Reinhard; Steinfartz, Sebastian; Grimm-Seyfarth, Annegret; Henle, Klaus (2023-06-01). "Habitat connectivity supports the local abundance of fire salamanders (Salamandra salamandra) but also the spread of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans". Landscape Ecology. 38 (6): 1537–1554. Bibcode:2023LaEco..38.1537B. doi:10.1007/s10980-023-01636-8. ISSN 1572-9761.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Berit (2024-04-19). "Kurzmitteilung: Vorläufiger Bericht über den Erstnachweis von Bsal (Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans) an Feuersalamandern im Freiland in Hessen". Feuersalamander Hessen (in German). Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- ^ Thein (2020). "Preliminary report on the occurrence of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans in the Steigerwald, Bavaria, Germany". Salamandra. 56 (3): 227–229.

- ^ Schmeller, Dirk; Utzel, Reinhard; Pasmans, Frank; Martel, An (2020). "Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans kills alpine newts (Ichthyosaura alpestris) in southernmost Germany". Salamandra. 56 (3): 230–232.

- ^ Böning, Philipp; Lötters, Stefan; Barzaghi, Benedetta; Bock, Marvin; Bok, Bobby; Bonato, Lucio; Ficetola, Gentile Francesco; Glaser, Florian; Griese, Josline; Grabher, Markus; Leroux, Camille; Munimanda, Gopikrishna; Manenti, Raoul; Ludwig, Gerda; Preininger, Doris (2024-05-17). "Alpine salamanders at risk? The current status of an emerging fungal pathogen". PLOS ONE. 19 (5): e0298591. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0298591. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 11101120. PMID 38758948.

- ^ Bosch, Jaime; Martel, An; Sopniewski, Jarrod; Thumsová, Barbora; Ayres, Cesar; Scheele, Ben C.; Velo-Antón, Guillermo; Pasmans, Frank (August 2021). "Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans Threat to the Iberian Urodele Hotspot". Journal of Fungi. 7 (8): 644. doi:10.3390/jof7080644. ISSN 2309-608X. PMC 8400424. PMID 34436183.

- ^ Carter, E. Davis (2020). "Conservation risk of Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans to endemic lungless salamanders". Conservation Letters. 13 (1). Bibcode:2020ConL...13E2675C. doi:10.1111/conl.12675.

- ^ Koo, Michell (October 4, 2021). "Tracking, Synthesizing, and Sharing Global Batrachochytrium Data at AmphibianDisease.org". Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 8. doi:10.3389/fvets.2021.728232. PMC 8527349. PMID 34692807.

- ^ Burke, Katie (6 February 2017). "New Disease Emerges as Threat to Salamanders". American Scientist.

- ^ "Amphibian Species By the Numbers".

- ^ Bishop, David. "Sustaining America's Aquatic Biodiversity, Salamnders Biodiversity and Consevation". Virginia Cooperative Extension.

- ^ Fisher, Mathew (Feb 25, 2020). "Chytrid fungi and global amphibian declines". Nature Reviews Microbiology. 18 (6): 332–343. doi:10.1038/s41579-020-0335-x. hdl:10044/1/78596. PMID 32099078. S2CID 211266075.

- ^ Gray, Matthew J.; Carter, Edward Davis; Piovia-Scott, Jonah; Cusaac, J. Patrick W.; Peterson, Anna C.; Whetstone, Ross D.; et al. (June 5, 2023). "Broad host susceptibility of North American amphibian species to Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans suggests high invasion potential and biodiversity risk". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 3270. Bibcode:2023NatCo..14.3270G. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-38979-4. PMC 10241899. PMID 37277333. Art. No. 3270.