Barry Commoner (May 28, 1917 – September 30, 2012) was an American cellular biologist, college professor, and politician. He was a leading ecologist and among the founders of the modern environmental movement. He was the director of the Center for Biology of Natural Systems[1][2] and its Critical Genetics Project.[3][4][5] He ran as the Citizens Party candidate in the 1980 U.S. presidential election.[6] His work studying the radioactive fallout from nuclear weapons testing led to the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963.[7]

Barry Commoner | |

|---|---|

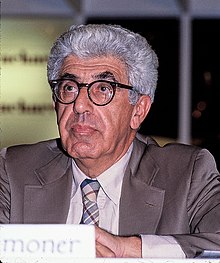

Commoner in 1980 | |

| Born | May 28, 1917 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 30, 2012 (aged 95) New York, New York, U.S. |

| Education | Columbia University Harvard University |

| Occupation | Biologist |

| Spouses |

Lisa Feiner (m. 1980) |

| Awards | Newcomb Cleveland Prize (1953) |

Early life

editCommoner was born in Brooklyn, New York, on May 28, 1917, the son of Jewish immigrants from Russia.[8] He received his bachelor's degree in zoology from Columbia University in 1937 and his master's and doctoral degrees from Harvard University in 1938 and 1941, respectively.[9][10]

Career in academia

editAfter serving as a lieutenant in the US Navy during World War II,[11] Commoner moved to St. Louis, Missouri, and he became an associate editor for Science Illustrated from 1946 to 1947.[12] He became a professor of plant physiology at Washington University in St. Louis in 1947 and taught there for 34 years. During this period, in 1966, he founded the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems to study "the science of the total environment".[1] Commoner was on the founding editorial board of the Journal of Theoretical Biology in 1961.

The greatest single cause of environmental contamination of this planet is radioactivity from test explosions of nuclear weapons in the atmosphere.

— Barry Commoner, Fallout and Water Pollution–Parallel Cases[13]

In the late 1950s, Commoner became known for his opposition to nuclear weapons testing, becoming part of the team which conducted the Baby Tooth Survey, demonstrating the presence of Strontium 90 in children's teeth as a direct result of nuclear fallout.[14][15] In 1958, he helped found the Greater St. Louis Committee on Nuclear Information.[16] Shortly thereafter, he established Nuclear Information, a mimeographed newsletter published in his office, which later went on to become Environment magazine.[14] Commoner went on to write several books about the negative ecological effects of atmospheric (i.e., above-ground) nuclear testing. In 1970, he received the International Humanist Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union.

Environmental books

editThe Closing Circle

editIn his 1971 bestselling book The Closing Circle, Commoner suggested that the US economy should be restructured to conform to the unbending laws of ecology.[17] For example, he argued that polluting products (like detergents or synthetic textiles) should be replaced with natural products (like soap or cotton and wool).[17] This book was one of the first to bring the idea of sustainability to a mass audience.[17] Commoner suggested a left-wing, eco-socialist response to the limits to growth thesis, postulating that capitalist technologies were chiefly responsible for environmental degradation, as opposed to population pressures. He had a long-running debate with Paul R. Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb and his followers, arguing that they were too focused on overpopulation as the source of environmental problems, and that their proposed solutions were politically unacceptable because of the coercion that they implied, and because the cost would fall disproportionately on the poor. He believed that technological, and above all, social, development would lead to a natural decrease in both population growth and environmental damage.[18]

One of Commoner's lasting legacies is his four laws of ecology, as written in The Closing Circle in 1971.[19] The four laws are:[20]

- Everything is connected to everything else. There is one ecosphere for all living organisms and what affects one, affects all.

- Everything must go somewhere. There is no "waste" in nature and there is no "away" to which things can be thrown.

- Nature knows best. Humankind has fashioned technology to improve upon nature, but such change in a natural system is, says Commoner, "likely to be detrimental to that system"

- There is no such thing as a free lunch. Exploitation of nature will inevitably involve the conversion of resources from useful to useless forms.

The Poverty of Power

editCommoner published another bestseller in 1976, The Poverty of Power.[17] In that book, he addressed the "three e's" that were plaguing the United States in the 1970s, the three e's being the environment, energy, and the economy.[21] "First there was the threat to environmental survival; then there was the apparent shortage of energy; and now there is the unexpected decline of the economy."[22] He argued that the three issues were interconnected: the industries that used the most energy had the highest negative impact on the environment. The focus on non-renewable resources as sources of energy meant that those resources were growing scarce, thus pushing up the price of energy and hurting the economy. Towards the book's end, Commoner suggested that the problem of the three e's is caused by the capitalistic system and can only be solved by replacing it with some sort of socialism.[17]

Making Peace with the Planet

editIn 1990, Commoner published Making Peace With the Planet, an analysis of the ongoing environmental crisis in which he argues that the way we produce goods needs to be reconstrued.

Poverty and population

editCommoner examined the relationship between poverty and population growth, disagreeing with the way that relationship is often formulated. He argued that rapid population growth of the developing world is the result of it not having adequate living standards, observing that it is poverty that "initiates the rise in population" before leveling off, not the other way around.[24] Developing countries were introduced to the living standards of developed nations, but were never able to fully adopt them, thus preventing these countries from advancing and thereby decreasing the rate of their population growth.

Commoner maintained that developing countries are still "forgotten" to colonialism. These developing countries were, and economically remain, "colonies of more developed countries".[24] Because Western nations introduced infrastructure developments such as roads, communications, engineering, and agricultural and medical services as a significant part of their exploitation of the developing nations' labor force and natural resources,[24] the first step towards a "demographic transition" was met, but other stages were not achieved because the wealth created in developing countries was "shipped out", so to speak, to the colonizer nations, enabling the latter to achieve the more advanced "levels of demographic transition", while the colonies continued on without achieving the second stage, which is population balancing.

"Thus colonialism involves a kind of demographic parasitism: the second population-balancing phase of the demographic transition in the advanced country is fed by suppression of that same phase in the colony".[24] "As the wealth of the exploited nations was diverted to the more powerful ones, their power, and with it their capacity to exploit increased. The gap between the wealth of nations grew, as the rich were fed by the poor".[24] This exploitation of resources extracted from developing nations, aside from its legality, led to an unforeseen problem: rapid population growth. The demographer, Nathan Keyfitz, concluded that, "the growth of industrial capitalism in the Western nations during the period 1800–1950 resulted in the development of a one-billion excess in the world population, largely in the tropics".[24]

This is evident in the study of India and contraceptives, in which family planning failed to reduce the birth rate because people felt that "in order to advance their economic situation", children were an economic necessity. The studies show that "population control in a country like India depends on the economically motivated desire to limit fertility".[24]

Commoner's solution is that wealthier nations need to help exploited or colonized countries develop and "achieve the level of welfare" that developed nations have. This is the only path to a balanced population in these developing countries. Commoner states that the only remedy for the world population crisis, which is the outcome of the abuse of poor nations by rich ones, is "returning to the poor countries enough of the wealth taken from them to give their peoples both the reason and the resources voluntarily to limit their own fertility".[24]

His conclusion is that poverty is the main cause of the population crisis. If the reason behind overpopulation in poor nations is the exploitation by rich nations made rich by that very exploitation, then the only way to end it is to "redistribute [the wealth], among nations and within them".[24]

2000 Dioxin Arctic study

editIn September 2000, a study published by the North American Commission on Environmental Cooperation, led by Commoner, found that Inuit women in the Arctic in Nunavut, Canada were found to have high levels of dioxin in their breast milk.[25] The study tracked the origin of the dioxins using computer models from the sources that produced it and found that the dioxin pollution in the Arctic originated from the United States.[26] Out of 44,000 sources of dioxin polluters in the United States, they found that only 19 were contributing to greater than a third of the dioxin pollution in Nunavut. Out of these 19, Harrisburg's incinerator was found to be the top source of dioxin pollution. [27][28][26] He was a recipient of the 2002 Joe A. Callaway Award for Civic Courage.[29]

Influence

editTime magazine introduced a section on the environment in their February 1970 issue, featuring articles on the "environmental crisis", and a quote from Richard Nixon's State of the Union address, calling it, "The great question of the '70s". Nixon said, "Shall we surrender to our surroundings or shall we make our peace with nature and begin to make reparations for the damage we have done to our air, to our land and to our water?"[30]

The magazine called Commoner, the "Paul Revere of ecology" for his work on the threats to life from the environmental consequences of fallout from nuclear tests and other pollutants of the water, soil, and air.[31] Time's cover represented a "call to arms", to mobilize public opinion by appeals to conscience.[23] The following month, the first Earth Day took place, which saw 20 million Americans demonstrating peacefully in favor of environmental reform, accompanied by several events held at university campuses across the US. The publications of Commoner are also considered influential in the decision of the Nixon administration in the following June to announce the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Clean Air Act of 1970.[23]

Environmental activism

editIn 1969, Commoner was one of the founders of the Missouri Coalition for the Environment, an independent citizens environmental advocacy organization.[32] His early guidance for this nonprofit led to multiple lawsuits that were won to protect the environment.

In 1980, Commoner founded the Citizens Party to serve as a vehicle for his ecological message, and he ran for president of the United States in the 1980 US election. His vice presidential running mate was La Donna Harris, the Native-American wife of Fred Harris, a former Democratic senator from Oklahoma, although she was replaced on the ballot in Ohio by Wretha Hanson.[33][34] His candidacy for president on the Citizens Party ticket won 233,052 votes (0.27 percent of the total).[35]

After his presidential bid, Commoner returned to New York City and moved the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems to Queens College. He stepped down from that post in 2000. At the time of his death, Commoner was a senior scientist at Queens College.

Personal life

editAfter serving in World War II, Commoner married the former Gloria Gordon, a St. Louis psychologist.[36] They had two children, Frederic and Lucy Commoner, and one granddaughter. Following a divorce, in 1980 he married Lisa Feiner,[37] whom he had met in the course of her work as a public-TV producer.

Death and legacy

editCommoner died on September 30, 2012, in Manhattan, New York.[38][39]

He was a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science and has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[40]

In 2014, the Center for Biology of Natural Systems[41] at Queens College was renamed The Barry Commoner Center for Health and the Environment.[42]

Works

edit- Books

- Science and Survival (1966), New York: Viking OCLC 225105 - on "the uses of science and technology in relation to environmental hazards"[16]

- The Closing Circle: Nature, Man, and Technology (1971), New York: Knopf ISBN 978-0-394-42350-0.

- The Poverty of Power: Energy and the Economic Crisis (1976), New York: Random House ISBN 978-0-394-40371-7.

- The Politics of Energy (1979), New York: Knopf ISBN 978-0-394-50800-9.

- Making Peace With the Planet (1990), New York: Pantheon ISBN 978-0-394-56598-9.

- Reports

- "Long-range Air Transport of Dioxin from North American Sources to Ecologically Vulnerable Receptors in Nunavut, Arctic Canada", (2000), Commoner, Barry; Bartlett, Paul Woods; Eisl, Holger; Couchot, Kim; Center for the Biology of Natural Systems, Queens College, City University of New York, published by the North American Commission for Environmental Cooperation, Montréal, Québec, Canada.

References

editNotes

edit- ^ a b Daum, Karl (Winter 2012–13). "Obituaries: Barry Commoner '37, Environmental and Social Activist". Columbia College Today. Columbia College. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

He also founded the Center for Biology of Natural Systems in 1966 to promote research on ecological systems. In 2000, he stepped down as director to concentrate on new research projects of his own.

- ^ "Barry Commoner". Barry Commoner Center for Health and the Environment. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Program". Critical Genetics Project. Queens College, City University of New York. December 4, 2002. Archived from the original on February 11, 2003. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

The program has been underway since February 2001. An initial analytical paper, "Unraveling the DNA Myth," has been published in the Harper's Magazine issue of February 2002....The Critical Genetics Project is a program of the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems (CBNS), Queens College, City University of New York

- ^ U.S. Newswire (January 2002). "New Report Challenges Fundamentals of Genetic Engineering; Study Questions Safety of Genetically Engineered Foods". The Pure Water Gazette. Pure Water Products, LLC. Archived from the original on April 19, 2021. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

The study reported in Harper's Magazine is the initial publication of a new initiative called The Critical Genetics Project directed by Dr. Commoner in collaboration with molecular geneticist Dr. Andreas Athanasiou, at the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems, Queens College, City University of New York.

- ^ Commoner, Barry (February 1, 2002). "Unraveling the DNA myth". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- ^ Vinciguerra, Thomas (June 19, 2007). "A Conversation with Barry Commoner: At 90, an Environmentalist From the '70s Still Has Hope". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Daniel (October 1, 2012). "Scientist, Candidate and Planet Earth's Lifeguard". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Rupert Cornwell (October 6, 2012). "Barry Commoner: Scientist who forced environmentalism into the world's consciousness". The Independent. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ "Barry Commoner, C250: Columbia Celebrates Columbians Ahead of their Time.". Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ^ "Barry Commoner '37, Environmental and Social Activist | Columbia College Today". www.college.columbia.edu. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- ^ Mongillo, John F. (2011). Environmental Activists. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 61.

- ^ Hamilton, Neil (2014). American Social Leaders and Activists. Infobase Publishing. p. 87.

- ^ Commoner, Barry (December 1964). "Fallout and Water Pollution–Parallel Cases". Scientist and Citizen. 7–2: 2. doi:10.1080/21551278.1964.9958599.

- ^ a b McGowan, Alan H. (March–April 2013). "Remembering Barry Commoner". Environment. 55 (2): 17. doi:10.1080/00139157.2013.765312. S2CID 154917172.

- ^ Krasner, William (March–April 2013). "Baby Tooth Survey: First Results". Environment. 55 (2): 18–24. doi:10.1080/00139157.2013.765314. S2CID 154576170. Reprinted from Nuclear Information 4 (1), 1961

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b Gottlieb, Robert. 1993. Forcing the Spring. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, p.172. ISBN 1-55963-122-8

- ^ a b c d e Herrera, Philip (May 31, 1976). "Books: Learning the Three Es". Time. Archived from the original on January 18, 2005. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- ^ Commoner, Barry (May 1972). "A Bulletin Dialogue: on "The Closing Circle" - Response". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 28: 17–56. doi:10.1080/00963402.1972.11457931.

Population control (as distinct from voluntary, self-initiated control of fertility), no matter how disguised, involves some measure of political repression, and would burden the poor nations with the social cost of a situation—overpopulation—which is the current outcome of their previous exploitation, as colonies, by the wealthy nations.

- ^ Egan, Michael (2007). Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival: The Remaking of American Environmentalism. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-262-05086-9.

- ^ Miller, Stephen (October 1, 2012). "Early Voice for Environment Warned About Radiation, Pollution". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

In his 1971 best seller The Closing Circle, Mr. Commoner posited four laws of ecology: that everything is connected, that everything must go somewhere, 'Nature knows best', and 'There is no such thing as a free lunch'.

- ^ Kalman, Laura (2010). Right Star Rising: A New Politics, 1974-1980. New York: W.W. Norton & Co., Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 9780393076387. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- ^ Barry Commoner, The Poverty of Power (1976), p. 1.

- ^ a b c Eldon H. Franz (2001). "Ecology, Values, and Policy". BioScience. 51 (6): 469–474. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0469:EVAP]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Commoner, Barry (August–September 1975). "How Poverty Breeds Overpopulation and Not the Other Way Around". Ramparts: 1–6. Archived from the original on July 20, 2012.

- ^ Lucas, Anne E. Lucas (2004). Rachel Stein (ed.). New Perspectives on Environmental Justice: Gender, Sexuality, and Activism. Rutgers University Press. p. 191.

- ^ a b Hilts, Philip (October 17, 2000). "Dioxin in Arctic Circle Is Traced to Sources Far to the South". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Commoner, Barry; et al. "Long-range Air Transport of Dioxin from North American Sources to Ecologically Vulnerable Receptors in Nunavut, Arctic Canada" (PDF). Commission for Environmental Cooperation. p. 83. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Capozza, Korey (June 6, 2009). "U.S. Hazardous to Health?". International Reporting Project. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

- ^ Joe A. Callaway Awards For Civic Courage Past-Winners, Calloway Awards, 2002. Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Fighting to Save the Earth from Man". Time. February 2, 1970.

- ^ "Environment: Paul Revere of Ecology". Time. February 2, 1970.

- ^ "History & Impact". Missouri Coalition for the Environment. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ [1] Archived November 20, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wood County, 1980-1989" (PDF). August 4, 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2003.

- ^ 1980 Presidential General Election Results, US Elections Atlas

- ^ "Barry Commoner Biography". The Gale Group, Inc. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Daniel (October 1, 2012). "Barry Commoner, Environmental Scientist and Scholar, Dies at 95". The New York Times. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ "Barry Commoner, Environmental Scientist and Scholar, Dies at 95". The New York Times. October 1, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

Barry Commoner, a founder of modern ecology and one of its most provocative thinkers and mobilizers, died Sunday in Manhattan. He was 95 and lived in Brooklyn Heights.

- ^ Dreier, Peter (October 1, 2012). "Barry Commoner, Pioneering Environmental Scientist and Activist, Dies at 95". Huffington Post. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on June 2, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "CBNS: Center for the Biology of Natural Systems". Center for the Biology of Natural Systems. Flushing, New York: Queens College, City University of New York. September 30, 1997. Archived from the original on October 12, 1997. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

CBNS is a research organization with considerable experience in the analysis of environmental, energy and resource problems and their economic implications. Established in 1966 at Washington University in St. Louis, CBNS moved to Queens College in 1981, where it is organized as a research institute of the City University of New York.

- ^ "Re-naming CBNS to the Barry Commoner Center of Health and the Environment". commonercenter.org/. Archived from the original on December 19, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

On December 2 at 4:30 pm, Queens College President Félix V. Matos Rodríguez will join Center faculty and staff to officially re-name the Center for the Biology of Natural Systems after its founder, Barry Commoner.

Further reading

edit- Contemporary Authors (2000). Detroit: Gale

- Who's Who in America (2004). Chicago: Marquis

- Egan, Michael (2007). Barry Commoner and the Science of Survival: The Remaking of American Environmentalism. Cambridge, MA: MIT. ISBN 978-0-262-05086-9.

External links

edit- Key Participants: Barry Commoner - Linus Pauling and the International Peace Movement: A Documentary History

- "Barry Commoner - Environmentalist", Flickr.com - Photo and conversation, from The New York Times

- Scientific American: Interview with Barry Commoner (June 23, 1997)

- New York Times: Scientist, Candidate and Planet Earth's Lifeguard (October 1, 2012)

- Dreier, Peter (October 1, 2012). "Remembering Barry Commoner". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378.

- "A Barry Commoner Quotation". solarhousehistory.com. December 14, 2014.