Barazoku (薔薇族) was Japan's first commercially circulated gay men's magazine. It began publication in July 1971 by Daini Shobō's owner's son and editor Bungaku Itō (伊藤 文學, Itō Bungaku), although before that, there had been Adonis and Apollo, its extra issue, around 1960 serving as a members-only magazine.[1] Barazoku was Japan's oldest and longest-running monthly magazine for gay men. However, it halted publication three times due to the publisher's financial hardships. In 2008, Itō announced that the 400th issue would be the final one.[2] The title means "the rose tribe" in Japanese, hinted from King Laius' homosexual episodes in Greek mythology. The magazine was printed in Japanese only. Barazoku's Bungaku Itō coined the term for the Japanese lesbian community as ("lily tribe") which the slang term for lesbian yuri comes from.

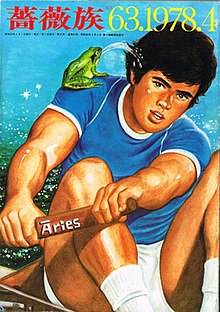

Cover of April 1978 issue | |

| Editor | Bungaku Itō |

|---|---|

| Categories | Gay |

| Frequency | Monthly |

| First issue | 1971 |

| Final issue Number | 2008 400 |

| Company | Daini Shobō |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Features

editAlong with much Japanese gay culture, gay magazines in Japan are segregated by type, aimed at an audience with specific interests. Barazoku, however, attempted to reach a broad audience and thus contained "a little something for everybody".[3] A typical issue of Barazoku had approximately 300 pages, including several pages of glossy color and black and white photographs of younger, fit men in their late teens and twenties (these photographs were censored in accordance with Japan's rules, which require the obscuring of genitals and pubic hair). Despite the inclusion of pornographic pictures, however, Barazoku was not a pornographic magazine.

The bulk of a typical issue of Barazoku consisted of articles and short stories, advice, how-tos, interviews, news, arts, and community listings. Compared to other gay magazines like "Badi", Barazoku typically had fewer pictures and manga stories and less news, which may have contributed to its demise.

Much of the magazine's revenue came from "personal ads" – advertisements placed by readers in search of romantic attachments, friends or sex partners. Such advertisements had long been a popular way for gay men to meet each other in Japan, but the advent of the internet, with its free dating sites, also contributed to the magazine's eventual end, especially when such sites became accessible from mobile phones.

Along with the rise in internet use and a decrease in paid advertising, Barazoku blamed its demise on the increasing inclusion of gay news in mainstream publications.

Barazoku was Japan's oldest gay magazine, and was in print for 33 years. First published in 1971, Barazoku was considered a trailblazer for other gay publications and a leader in Japanese gay culture.[citation needed] In its 33 years, the magazine survived despite mainstream disapproval and legal injunctions.

Barazoku was the first gay magazine in Asia to be sold at mainstream bookshops, such as Kinokuniya. It became such a cultural phenomenon that its title has entered the mainstream language as a synonym for "gay" and gay manga.

In its early years, the magazine published artwork by Go Mishima and Rune Naito. Founder Ito's determination to fight discrimination led the magazine to publish an interview with Japan's first known AIDS sufferer at a time when the mainstream media refused to address the issue.

The demise of Barazoku may have come as a blow to gays in isolated communities in Japan: the magazine's strongest sales came from small, independent bookshops in such areas.

Several attempts were made to restart the magazine: twice in 2005, and then again in 2007.[4]

Publication history

editOrigins

editBungaku Ito, the magazine's promoter, had been publishing books for oppressed gay people in Japan since 1968, such as Homo Techniques: Sex Life between a Man and another Man (ホモテクニックー男と男の性生活, Homo Tekunikku - Otoko to Otoko no Seiseikatsu) and Lesbian Techniques: Sex Life between a Woman and another Woman (レスビアンテクニックー女と女の性生活, Resubian Tekunikku - Onna to Onna no Seiseikatsu). With their success, he became confident that Japan's first gay magazine would also be welcomed. In 1970, Ito announced in one of his publications his intent to launch a gay magazine in order to reduce prejudices in mainstream culture and to encourage gay people that they deserved better lives and brighter futures. As a result, two men, Ryu Fujita and Hiroshi Mamiya, contacted Ito for employment as editors. Fortunately for heterosexual Ito, both of them were gay and experienced writers/editors, having worked for minor magazines. As Ito lacked experience in publishing magazines, most content in the first issue of Barazoku, including essays, photographs and illustrations, were made by Fujita and Mamiya. In the meantime, Ito attempted to convince bookstore agencies like Tohan that offering his magazine in mainstream bookstores would be profitable. Initially, Tohan rejected it, thinking that neither men nor women would be interested in this genre of magazine, but finally accepted it as Ito's other books for gay people had outsold their expectations.[5]

The magazine was named Barazoku (The Rose Tribe) by Ito since the rose had been a prominent symbol of male homosexuality in Japan, derived from the Greek myth of the King Laius having affairs with boys under rose trees. The first issue was published on 30 July 1971, with 72 pages including only 6 pages of nude photographs, and the price was 260 yen a copy. It was sold in major bookstores such as Books Kinokuniya in Shinjuku and Shibuya. Most of the first 10,000 copies were sold out shortly. After that, the news of the successful launch of Japan's first gay magazine became a hot topic in other magazines. Ito reasoned that the popularity was due to the fact that the two editors' favorite "type" was sporty young men, which was popular among gay readers.[6]

1970s and controversies

editEncouraged by the first issue's success, Ito published a second issue in November 1972. However, one of the nude photographs titled "Summer of '52: Omoide no Natsu" (Summer Memories) was found obscene by censorship authorities because the pubic hair on one of the models had not been properly masked. Ito feared he would be penalized, even banned from further publication of Barazoku, but received only a warning that no pubic hair would appear in future issues.[7] Ito continued to publish Barazoku bi-monthly, with increasing sales.[8]

In 1973, Barazoku salvaged a short story "Ai no Shokei" ("Worse for Love") by Tamotsu Sakakiyama from the 1960s members-only gay magazine Apollo. Since first appearing in 1960, the story had been rumored to be written by renowned author Yukio Mishima for its similarities with Mishima's 1960 short story "Yukoku" ("Patriotism"). Barazoku invited regular contributors along with university professor Masamichi Abe and film critic Tatsuji Okawa to participate in a debate over the rumor's veracity. Abe admitted that there were similarities between "Ai no Shokei" and "Yukoku," but did not contend that both works were written by Mishima. On the other hand, Barazoku's editor Ryu Fujita and novelist Mansaku Arashi both insisted that "Ai no Shokei" had been written by Mishima under a pseudonym. In 2005, 32 years after the discussion, it was determined that Fujita and Arashi were correct.[9]

Starting in 1974, Ito began publishing Barazoku monthly in order to compete with Adon, a new gay magazine launched by Sadashiro Minami, a former writer for Barazoku.[10] Monthly publication of Barazoku was welcomed by readers and circulation increased. In 1975, however, a serially-published erotic novel "Danshoku Saiyuki" (Gay Journey to the West), which began with the April issue, was found to be obscene. This time Ito and the novel's author Mansaku Arashi were summoned and interrogated harshly, until the investigators discovered that Arashi was related to a former Japanese prime minister. The investigation was closed and Ito and Arashi were not criminalized, but further sale of the April 1975 issue was forbidden.[11]

In 1976, Ito opened a cafe named "Matsuri" (Carnival) in Shinjuku as a social space for Barazoku's readers. Ito thought that not many visitors would dare to be seen as gay, but the cafe instantly became very popular, and Ito needed to open multiple locations when the first Matsuri was unable to handle all the visitors. Another cafe, "Ribonnu" (Ribbon Girl), was opened for lesbian clientele in the same district.[12]

By the end of the 1970s, Barazoku became much thicker in volume with more articles and photographs, and the price went up to 500 yen. The price increase was welcomed by readers who did not want to be seen when buying the gay magazine, as they did not have to wait for change if they give a 500-yen note.[13]

1980s: rise of Bara products and AIDS

editIn 1981, Barazoku began selling gay videos, which turned out to be another success. Ito stated that although purchasing such videos via mail-order had been considered unsafe, many people placed orders as they trusted Barazoku's reputation. One of the pilot titles "Bara to Umi to Taiyo to" (Roses, the Sea and the Sun) became popular and was later shown in movie theaters with the catchphrase "Barazoku Eiga (movie)". Since then, male gay movies in Japan have all been labeled as "Barazoku Eiga", regardless of who produced them.[14]

In 1982, Ito produced a lubricant product named "Love Oil". He appealed to the readers that for safer and better sex, they should use condoms and put Love Oil over it. It became another popular product, with average sales of 4,000–5,000 bottles a month.[15]

In 1985, Barazoku staff arranged to interview an AIDS patient. It was the first interview between a Japanese AIDS patient and a member of the media.[16]

Barazoku also published extra issues featuring gay manga, including the now-famous works of Junichi Yamakawa, such as "Kuso Miso Technique" (1987). However, Yamakawa's style was disliked by the editors except for Ito himself. Eventually Yamakawa stopped visiting Ito and still had not been in contact since then.[17]

References

edit- ^ "Japan's first magazine, and the first in Asia, dedicated to gay men, Barazoku, was launched in 1971". Red Circle Authors. 28 February 2020. Archived from the original on 28 September 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ 薔薇族 [The Rose Tribe]. Daini Shobo. 2008. pp. 46–55.

- ^ McLelland, Mark J. (2000). Male homosexuality in modern Japan: cultural myths and social realities. Routledge. p. 134. ISBN 0-7007-1300-X.

- ^ Connell, Ryann (20 April 2007). "Iconic gay magazine has revolving door installed in financial closet". Mainichi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2007.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 18–35. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 35–37. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 48–51. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. p. 58. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 薔薇よ永遠に - 薔薇族編集長35年の闘い [Roses Forever: 35 years of resistance by the chief of the rose tribe]. Kyutensha. pp. 124–206. ISBN 4-86167-114-0.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 59–60. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 152–154. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 208–218. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. p. 219. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2006). 『薔薇族』編集長 [The Chief of Barazoku]. Gentosha Outlaw Bunko. pp. 223–226. ISBN 978-4-344-40864-7.

- ^ "「ラブオイル」発売してから25年も!". Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Ito, Bungaku (2001). 薔薇ひらく日を - 薔薇族と共に歩んだ30年 [The Day When The Roses Bloom: 30 years with the rose tribe]. Kawaide Shobo Shinsha. pp. 144–145. ISBN 4-309-90455-6.

- ^ "山川純一作品の原画がみつかった!". Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- Lewis, Leo and Tim Teeman: "Voice of gay Japan falls silent after 30 years in the pink", "The Times".

- Mackintosh, Jonathan D. "Itō Bungaku and the Solidarity of the Rose Tribes (Barazoku): Stirrings of Homo Solidarity in Early 1970s Japan". "Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context", Issue 12, January 2006.

External links

edit- Barazoku website (in Japanese)