The Ballets Russes (French: [balɛ ʁys]) was an itinerant ballet company begun in Paris that performed between 1909 and 1929 throughout Europe and on tours to North and South America. The company never performed in Russia, where the Revolution disrupted society. After its initial Paris season, the company had no formal ties there.[1]

| Ballets Russes | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Name | Ballets Russes |

| Year founded | 1909 |

| Closed | 1929 |

| Principal venue | various |

| Artistic staff | |

| Artistic Director | Sergei Diaghilev |

| Other | |

| Formation |

|

Originally conceived by impresario Sergei Diaghilev, the Ballets Russes is widely regarded as the most influential ballet company of the 20th century,[2] in part because it promoted ground-breaking artistic collaborations among young choreographers, composers, designers, and dancers, all at the forefront of their several fields. Diaghilev commissioned works from composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, Sergei Prokofiev, Erik Satie, and Maurice Ravel, artists such as Vasily Kandinsky, Alexandre Benois, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, and costume designers Léon Bakst and Coco Chanel.

The company's productions created a huge sensation, completely reinvigorating the art of performing dance, bringing many visual artists to public attention, and significantly affecting the course of musical composition. It also introduced European and American audiences to tales, music, and design motifs drawn from Russian folklore. The company's employment of European avant-garde art went on to influence broader artistic and popular culture of the early twentieth century, not least the development of Art Deco.

Nomenclature

editThe French plural form of the name, Ballets Russes, specifically refers to the company founded by Sergei Diaghilev and active during his lifetime. (In some publicity the company was advertised as Les Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghileff.) In English, the company is now commonly referred to as "the Ballets Russes", although in the early part of the 20th century, it was sometimes referred to as "The Russian Ballet" or "Diaghilev's Russian Ballet." To add to the confusion, some publicity material spelled the name in the singular.

The names Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo and the Original Ballet Russe (using the singular) refer to companies that formed after Diaghilev's death in 1929.

History and productions

editBackground

editSergei Diaghilev, the company's impresario (or "artistic director" in modern terms), was chiefly responsible for its success. He was uniquely prepared for the role; born into a wealthy Russian family of vodka distillers (though they went bankrupt when he was 18), he was accustomed to moving in the upper-class circles that provided the company's patrons and benefactors. It's indispensable to mention the name of the sponsor Winnaretta Singer which generous financial subsides ensured the success of Sergei Diaghilev's Ballets Russes in Europe.[3]

In 1890, he enrolled at the Faculty of Law, St. Petersburg, to prepare for a career in the civil service like many Russian young men of his class.[4] There he was introduced (through his cousin Dmitry Filosofov) to a student clique of artists and intellectuals calling themselves The Nevsky Pickwickians whose most influential member was Alexandre Benois; others included Léon Bakst, Walter Nouvel, and Konstantin Somov.[4] From childhood, Diaghilev had been passionately interested in music. However, his ambition to become a composer was dashed in 1894 when Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov told him he had no talent.[5]

In 1898, several members of The Pickwickians founded the journal Mir iskusstva (World of Art) under the editorship of Diaghilev.[6] As early as 1902, Mir iskusstva included reviews of concerts, operas, and ballets in Russia. The latter were chiefly written by Benois, who exerted considerable influence on Diaghilev's thinking.[7] Mir iskusstva also sponsored exhibitions of Russian art in St. Petersburg, culminating in Diaghilev's important 1905 show of Russian portraiture at the Tauride Palace.[8]

Frustrated by the extreme conservatism of the Russian art world, Diaghilev organized the groundbreaking Exhibition of Russian Art at the Petit Palais in Paris in 1906, the first major showing of Russian art in the West. Its enormous success created a Parisian fascination with all things Russian. Diaghilev organized a 1907 season of Russian music at the Paris Opéra. In 1908, Diaghilev returned to the Paris Opéra with six performances of Modest Mussorgsky's opera Boris Godunov, starring basso Fyodor Chaliapin. This was Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's 1908 version (with additional cuts and re-arrangement of the scenes). The performances were a sensation, though the costs of producing grand opera were crippling.

Debut

editIn 1909, Diaghilev presented his first Paris "Saison Russe" devoted exclusively to ballet (although the company did not use the name "Ballets Russes" until the following year). Most of this original company were resident performers at the Imperial Ballet of Saint Petersburg, hired by Diaghilev to perform in Paris during the Imperial Ballet's summer holidays. The first season's repertory featured a variety of works chiefly choreographed by Michel Fokine, including Le Pavillon d'Armide, the Polovtsian Dances (from Prince Igor), Les Sylphides, and Cléopâtre. The season also included Le Festin, a pastiche set by several choreographers (including Fokine) to music by several Russian composers.

Principal productions

editThe principal productions are shown in the table below.

| Year | Title | Image | Composer(s) | Choreographer(s) | Sets and costumes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1909 | Le Pavillon d'Armide | Nikolai Tcherepnin | Michel Fokine | Alexandre Benois | |

| Prince Igor | Alexander Borodin | Michel Fokine | Nicholas Roerich | ||

| Le Festin | Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (march from Le Coq d'Or used for processional entry) | Konstantin Korovin (sets and costumes)

Léon Bakst (costumes) Alexandre Benois (costumes) Ivan Bilibin (costumes) | |||

| Mikhail Glinka ("Lezginka" from Ruslan and Ludmilla) | Michel Fokine, Marius Petipa | ||||

| Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ("L'Oiseau d'Or" from The Sleeping Beauty) | Marius Petipa | ||||

| Alexander Glazunov ("Czardas" from Raymonda) | Alexander Gorsky | ||||

| Modest Mussorgsky ("Hopak" from The Fair at Sorochyntsi) | Michel Fokine | ||||

| Mikhail Glinka ("Mazurka" from A Life for the Tsar) | Nicolai Goltz, Felix Kchessinsky | ||||

| Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ("Trepak" from The Nutcracker) | Michel Fokine | ||||

| Alexander Glazunov ("Grand Pas Classique Hongrois" from Raymonda) | Marius Petipa | ||||

| Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky ("Finale" of the Second Symphony) | Michel Fokine | ||||

| Les Sylphides | Frédéric Chopin (orch. Glazunov, Igor Stravinsky, Alexander Taneyev) | Michel Fokine | Alexandre Benois | ||

| Cléopâtre | Anton Arensky (additional music by Glazunov, Glinka, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Sergei Taneyev, Nikolai Tcherepnin) | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| 1910 | Carnaval | Robert Schumann (orch. Arensky, Glazunov, Anatol Liadov, Rimsky-Korsakov, Tcherepnin) | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | |

| Schéhérazade | Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Giselle | Adolphe Adam | Jean Coralli, Jules Perrot, Marius Petipa (revival), Michel Fokine (revisions) | Alexandre Benois | ||

| Les Orientales | Christian Sinding (Rondoletto giocoso, op.32/5) (orch. Igor Stravinsky for "Danse Siamoise")

Edvard Grieg (Småtroll, op.71/3, from Lyric Pieces, Book X) (orch. Igor Stravinsky for "Variation") |

Vaslav Nijinsky ("Danse Orientale" and "Variation")

Michel Fokine |

Konstantin Korovin (sets and costumes)

Léon Bakst (costumes) | ||

| L'Oiseau de feu | Igor Stravinsky | Michel Fokine | Alexander Golovine (sets and costumes)

Léon Bakst (costumes) | ||

| 1911 | Le Spectre de la rose | Carl Maria von Weber | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | |

| Narcisse | Nikolai Tcherepnin | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Sadko | Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | Mikhail Fokine | Boris Anisfeld | ||

| Petrushka | Igor Stravinsky | Michel Fokine | Alexandre Benois | ||

| Swan Lake | Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky | Marius Petipa, Lev Ivanov, Michel Fokine (revisions) | Konstantin Korovin (sets)

Alexander Golovin (sets and costumes) | ||

| 1912 | L'après-midi d'un faune | Claude Debussy | Vaslav Nijinsky | Léon Bakst | |

| Daphnis et Chloé | Maurice Ravel | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Le Dieu bleu | Reynaldo Hahn | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Thamar | Mily Balakirev based on his symphonic Poem Tamara | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| 1913 | Jeux | Claude Debussy | Vaslav Nijinsky | Léon Bakst | |

| Le sacre du printemps | Igor Stravinsky | Vaslav Nijinsky | Nicholas Roerich | ||

| Tragédie de Salomé | Florent Schmitt | Boris Romanov | Sergey Sudeykin | ||

| 1914 | Les Papillons | Robert Schumann (orch. Nikolai Tcherepnin) | Mikhail Fokine | Mstislav Doboujinsky | |

| La légende de Joseph | Richard Strauss | Michel Fokine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Le coq d'or | Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | Michel Fokine | Natalia Goncharova | ||

| Le rossignol | Igor Stravinsky | Boris Romanov | Alexandre Benois | ||

| Midas | Maximilian Steinberg | Michel Fokine | Mstislav Doboujinsky | ||

| 1915 | Soleil de Nuit | Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov | Léonide Massine | Mikhail Larionov | |

| 1916 | Las Meniñas | Louis Aubert, Gabriel Fauré (Pavane), Maurice Ravel (Alborada del gracioso), Emmanuel Chabrier (Menuet pompeux) | Léonide Massine | Josep Maria Sert (costumes) | |

| Kikimora | Anatoly Liadov | Léonide Massine | Mikhail Larionov | ||

| Till Eulenspiegel | Richard Strauss | Vaslav Nijinsky | Robert Edmond Jones | ||

| 1917 | Feu d'Artifice | Igor Stravinsky | Giacomo Balla | ||

| Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur | Domenico Scarlatti (orch. Vincenzo Tommasini) | Léonide Massine | Léon Bakst | ||

| Parade | Erik Satie | Léonide Massine | Pablo Picasso | ||

| 1919 | La Boutique fantasque | Gioachino Rossini (arr. Ottorino Respighi) | Léonide Massine | André Derain | |

| El sombrero de tres picos | Manuel de Falla | Léonide Massine | Pablo Picasso | ||

| Les jardins d'Aranjuez (new version of Las Meninas) | Louis Aubert, Gabriel Fauré, Maurice Ravel, Emmanuel Chabrier | Léonide Massine | Josep Maria Sert (costumes) | ||

| 1920 | Le chant du rossignol | Igor Stravinsky | Léonide Massine | Henri Matisse | |

| Pulcinella | Igor Stravinsky | Léonide Massine | Pablo Picasso | ||

| Ballet de l'astuce féminine or Cimarosiana | Domenico Cimarosa | Léonide Massine | Josep Maria Sert | ||

| Le sacre du printemps (revival) | Igor Stravinsky | Léonide Massine | Nicholas Roerich | ||

| 1921 | Chout | Sergei Prokofiev | Léonide Massine | Mikhail Larionov | |

| Cuadro Flamenco | Traditional Andalusian music (arr. Manuel de Falla) | Pablo Picasso | |||

| The Sleeping Beauty | Pyotr Tchaikovsky | Marius Petipa | Léon Bakst | ||

| 1922 | Le Mariage de la Belle au Bois Dormant | Pyotr Tchaikovsky | Marius Petipa | Alexandre Benois (sets and costumes)

Natalia Goncharova (costumes) | |

| Mavra | Igor Stravinsky | Bronislava Nijinska | Léopold Survage | ||

| Renard | Igor Stravinsky | Bronislava Nijinska | Mikhail Larionov | ||

| 1923 | Les noces | Igor Stravinsky | Bronislava Nijinska | Natalia Goncharova | |

| 1924 | Les Tentations de la Bergère, ou l'Amour Vainqueur | Michel de Montéclair (arr. and orch. Henri Casadesus) | Bronislava Nijinska | Juan Gris | |

| Le Médecin malgré lui | Charles Gounod | Bronislava Nijinska | Alexandre Benois | ||

| Les biches | Francis Poulenc | Bronislava Nijinska | Marie Laurencin | ||

| Cimarosiana | Domenico Cimarosa (orch. Ottorino Respighi) | Léonide Massine, Bronislava Nijinska | José-María Sert | ||

| Les Fâcheux | Georges Auric | Bronislava Nijinska | Georges Braque | ||

| Le train bleu | Darius Milhaud | Bronislava Nijinska | Henri Laurens (sets)

Gabrielle Chanel (costumes) Pablo Picasso (sets) | ||

| 1925 | Zephyr et Flore | Vladimir Dukelsky | Léonide Massine | Georges Braque | |

| Le chant du rossignol (revival) | Igor Stravinsky | George Balanchine | Henri Matisse | ||

| Les matelots | Georges Auric | Léonide Massine | Pere Pruna | ||

| Barabau | Vittorio Rieti | George Balanchine | Maurice Utrillo | ||

| 1926 | Roméo et Juliette | Constant Lambert | Bronislava Nijinska | Max Ernst (curtain)

Joan Miró (sets and costumes) | |

| Pastorale | Georges Auric | George Balanchine | Pere Pruna | ||

| Jack in the Box | Erik Satie (orch. Milhaud) | George Balanchine | André Derain | ||

| The Triumph of Neptune | Lord Berners | George Balanchine | Pedro Pruna (costumes) | ||

| 1927 | La chatte | Henri Sauguet | George Balanchine | Naum Gabo | |

| Mercure | Erik Satie | Léonide Massine | Pablo Picasso | ||

| Le pas d'acier | Sergei Prokofiev | Léonide Massine | Georgy Yakulov | ||

| 1928 | Ode | Nikolai Nabokov | Léonide Massine | Pavel Tchelitchev | |

| Apollon musagète (Apollo) | Igor Stravinsky | George Balanchine | André Bauschant (scene)

Coco Chanel (costumes) | ||

| The Gods Go A-Begging | George Frederic Handel | George Balanchine | Léon Bakst (sets)

Juan Gris (costumes) | ||

| 1929 | Le Bal | Vittorio Rieti | George Balanchine | Giorgio de Chirico | |

| Renard (revival) | Igor Stravinsky | Serge Lifar | Mikhail Larionov | ||

| Le fils prodigue | Sergei Prokofiev | George Balanchine | Georges Rouault |

Successors

editWhen Sergei Diaghilev died of diabetes in Venice on 19 August 1929, the Ballets Russes was left with substantial debts. As the Great Depression began, its property was claimed by its creditors and the company of dancers dispersed.

In 1931, Colonel Wassily de Basil (a Russian émigré entrepreneur from Paris) and René Blum (ballet director at the Monte Carlo Opera) founded the Ballets Russes de Monte-Carlo, giving its first performances there in 1932.[9] Diaghilev alumni Léonide Massine and George Balanchine worked as choreographers with the company and Tamara Toumanova was a principal dancer.

Artistic differences led to a split between Blum and de Basil,[10] after which de Basil renamed his company initially "Ballets Russes de Colonel W. de Basil".[11] Blum retained the name "Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo", while de Basil created a new company. In 1938, he called it "The Covent Garden Russian Ballet"[11] and then renamed it the "Original Ballet Russe" in 1939.[11][12]

Col de Basil's company was run by famed promoter Fortune Gallo for a year after losing their manager.[13]

After World War II began, the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo left Europe and toured extensively in the United States and South America. As dancers retired and left the company, they often founded dance studios in the United States or South America or taught at other former company dancers' studios. With Balanchine's founding of the School of American Ballet, and later the New York City Ballet, many outstanding former Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo dancers went to New York to teach in his school. When they toured the United States, Cyd Charisse, the film actress and dancer, was taken into the cast.

The Original Ballet Russe toured mostly in Europe. Its alumni were influential in teaching classical Russian ballet technique in European schools.

The successor companies were the subject of the 2005 documentary film Ballets Russes.

The dancers

editThe Ballets Russes was noted for the high standard of its dancers, most of whom had been classically trained at the great Imperial schools in Moscow and St. Petersburg. Their high technical standards contributed a great deal to the company's success in Paris, where dance technique had declined markedly since the 1830s.

Principal female dancers included: Anna Pavlova, Tamara Karsavina, Olga Spessivtseva, Mathilde Kschessinska, Ida Rubinstein, Bronislava Nijinska, Lydia Lopokova, Sophie Pflanz, and Alicia Markova, among others; many earned international renown with the company, including Ekaterina Galanta and Valentina Kachouba.[14][15] Prima ballerina Xenia Makletzova was dismissed from the company in 1916 and sued by Diaghilev; she countersued for breach of contract, and won $4500 in a Massachusetts court.[16][17]

The Ballets Russes was even more remarkable for raising the status of the male dancer, largely ignored by choreographers and ballet audiences since the early 19th century. Among the male dancers were Michel Fokine, Serge Lifar, Léonide Massine, Anton Dolin, George Balanchine, Valentin Zeglovsky, Theodore Kosloff, Adolph Bolm, and the legendary Vaslav Nijinsky, considered the most popular and talented dancer in the company's history.

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, in later years, younger dancers were taken from those trained in Paris by former Imperial dancers, within the large community of Russian exiles. Recruits were even accepted from America and included a young Ruth Page who joined the troupe in Monte Carlo during 1925.[18][19][20]

Choreographers

editThe company featured and premiered now-famous (and sometimes notorious) works by the great choreographers Marius Petipa and Michel Fokine, as well as new works by Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska, Léonide Massine, and the young George Balanchine at the start of his career.

Michel Fokine

editThe choreography of Michel Fokine was of paramount importance in the initial success of the Ballets Russes. Fokine had graduated from the Imperial Ballet School in Saint Petersburg in 1898, and eventually become First Soloist at the Mariinsky Theater. In 1907, Fokine choreographed his first work for the Imperial Russian Ballet, Le Pavillon d'Armide. In the same year, he created Chopiniana to piano music by the composer Frédéric Chopin as orchestrated by Alexander Glazunov. This was an early example of creating choreography to an existing score rather than to music specifically written for the ballet, a departure from the normal practice at the time.

Fokine established an international reputation with his works choreographed during the first four seasons (1909–1912) of the Ballets Russes. These included the Polovtsian Dances (from Prince Igor), Le Pavillon d'Armide (a revival of his 1907 production for the Imperial Russian Ballet), Les Sylphides (a reworking of his earlier Chopiniana), The Firebird, Le Spectre de la Rose, Petrushka, and Daphnis and Chloé . After a longstanding tumultuous relationship with Diaghilev, Fokine left the Ballets Russes at the end of the 1912 season.[21]

Vaslav Nijinsky

editVaslav Nijinsky had attended the Imperial Ballet School, St. Petersburg since the age of eight. He graduated in 1907 and joined the Imperial Ballet where he immediately began to take starring roles. Diaghilev invited him to join the Ballets Russes for its first Paris season.

In 1912, Diaghilev gave Nijinsky his first opportunity as a choreographer, for his production of L'Après-midi d'un faune to Claude Debussy's symphonic poem Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune. Featuring Nijinsky himself as the Faun, the ballet's frankly erotic nature caused a sensation.[citation needed] The following year, Nijinsky choreographed a new work by Debussy composed expressly for the Ballets Russes, Jeux. Indifferently received by the public, Jeux was eclipsed two weeks later by the premiere of Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring (Le Sacre du printemps), also choreographed by Nijinsky.

Nijinsky eventually retired from dance and choreography, after he was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1919.

Léonide Massine

editLéonide Massine was born in Moscow,[22] where he studied both acting and dancing at the Imperial School. On the verge of becoming an actor, Massine was invited by Sergei Diaghilev to join the Ballets Russes, as he was seeking a replacement for Vaslav Nijinsky. Diaghilev encouraged Massine's creativity and his entry into choreography.

Massine's most famous creations for the Ballets Russes were Parade, El sombrero de tres picos, and Pulcinella. In all three of these works, he collaborated with Pablo Picasso, who designed the sets and costumes.

Massine extended Fokine's choreographic innovations, especially those relating to narrative and character. His ballets incorporated both folk dance and demi-charactère dance, a style using classical technique to perform character dance. Massine created contrasts in his choreography, such as synchronized yet individual movement, or small-group dance patterns within the corps de ballet.

Bronislava Nijinska

editBronislava Nijinska was the younger sister of Vaslav Nijinsky. She trained at the Imperial Ballet School in St. Petersburg, joining the Imperial Ballet company in 1908. From 1909, she (like her brother) was a member of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes.

In 1915, Nijinska and her husband fled to Kiev to escape World War I. There, she founded the École de movement, where she trained Ukrainian artists in modern dance. Her most prominent pupil was Serge Lifar (who later joined the Ballets Russes in 1923).

Following the Russian Revolution, Nijinska fled again to Poland, and then, in 1921, re-joined the Ballets Russes in Paris. In 1923, Diaghilev assigned her the choreography of Stravinsky's Les Noces. The result combines elements of her brother's choreography for The Rite of Spring with more traditional aspects of ballet, such as dancing en pointe. The following year, she choreographed three new works for the company: Les biches, Les Fâcheux, and Le train bleu.

George Balanchine

editBorn Giorgi Melitonovitch Balanchivadze in Saint Petersburg, George Balanchine was trained at the Imperial School of Ballet. His education there was interrupted by the Russian Revolution of 1917. Balanchine graduated in 1921, after the school reopened. He subsequently studied music theory, composition, and advanced piano at the Petrograd Conservatory, graduating in 1923. During this time, he worked with the corps de ballet of the Mariinsky Theater. In 1924, Balanchine (and his first wife, ballerina Tamara Geva) fled to Paris while on tour of Germany with the Soviet State Dancers. He was invited by Sergei Diaghilev to join the Ballets Russes as a choreographer.[23]

The designers

editDiaghilev invited the collaboration of contemporary fine artists in the design of sets and costumes. These included Alexandre Benois, Léon Bakst, Nicholas Roerich, Georges Braque, Natalia Goncharova, Mikhail Larionov, Pablo Picasso, Coco Chanel, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Joan Miró, Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Ivan Bilibin, Juan Gris, Pavel Tchelitchev, Maurice Utrillo, and Georges Rouault.

Their designs contributed to the groundbreaking excitement of the company's productions. The scandal caused by the premiere performance in Paris of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring has been partly attributed to the provocative aesthetic of the costumes of the Ballets Russes.[24]

While they created amazing works most of the designers were not trained in theater but started out as studio painters.

Alexandre Benois

editAlexandre Benois had been the most influential member of The Nevsky Pickwickians and was one of the original founders (with Bakst and Diaghilev) of Mir iskusstva. His particular interest in ballet as an art form strongly influenced Diaghilev and was seminal in the formation of the Ballets Russes. Benois was also focused on historical accuracy and had an extensive knowledge of fashion history. In addition, Benois contributed scenic and costume designs to several of the company's earlier productions: Le Pavillon d'Armide, portions of Le Festin, and Giselle. Benois also participated with Igor Stravinsky and Michel Fokine in the creation of Petrushka, to which he contributed much of the scenario as well as the stage sets and costumes.

Léon Bakst

editLéon Bakst was also an original member of both The Nevsky Pickwickians and Mir iskusstva. “He regarded the nude body as an aesthetic totality whose artistry had been forgotten under the weight of nineteenth century social and theatrical dress".”[25] He participated as designer in productions of the Ballets Russes from its beginning in 1909 until 1921, creating sets and costumes for Scheherazade, The Firebird, Les Orientales, Le Spectre de la rose, L'Après-midi d'une faune, and Daphnis et Chloé, among other productions.

Pablo Picasso

editIn 1917, Pablo Picasso designed sets and costumes in the Cubist style for three Diaghilev ballets, all with choreography by Léonide Massine: Parade, El sombrero de tres picos, and Pulcinella.

Natalia Goncharova

editNatalia Goncharova was born in 1881 near Tula, Russia. Her art was inspired by Russian folk art, Fauvism, and cubism. She began designing for the Ballets Russes in 1921.

Although the Ballets Russes firmly established the 20th-century tradition of fine art theatre design, the company was not unique in its employment of fine artists. For instance, Savva Mamontov's Private Opera Company had made a policy of employing fine artists, such as Konstantin Korovin and Golovin, who went on to work for the Ballets Russes.

Composers and conductors

editFor his new productions, Diaghilev commissioned the foremost composers of the 20th century, including: Debussy, Milhaud, Poulenc, Prokofiev, Ravel, Satie, Respighi, Stravinsky, de Falla, and Strauss. He was also responsible for commissioning the first two significant British-composed ballets: Romeo and Juliet (composed in 1925 by nineteen-year-old Constant Lambert) and The Triumph of Neptune (composed in 1926 by Lord Berners).

The impresario also engaged conductors who were or became eminent in their field during the 20th century, including Pierre Monteux (1911–16 and 1924), Ernest Ansermet (1915–23), Edward Clark (1919–20) and Roger Désormière (1925–29).[26]

Igor Stravinsky

editDiaghilev hired the young Stravinsky at a time when he was virtually unknown to compose the music for The Firebird, after the composer Anatoly Lyadov proved unreliable, and this was instrumental in launching Stravinsky's career in Europe and the United States of America.

Stravinsky's early ballet scores were the subject of much discussion. The Firebird (1910) was seen as an astonishingly accomplished work for such a young artist (Debussy is said to have remarked drily: "Well, you've got to start somewhere!"). Many contemporary audiences found Petrushka (1911) to be almost unbearably dissonant and confused. The Rite of Spring (1913) nearly caused an audience riot. It stunned people because of its willful rhythms and aggressive dynamics. The audience's negative reaction to it is now regarded as a theatrical scandal as notorious as the failed runs of Richard Wagner's Tannhäuser at Paris in 1861 and Jean-Georges Noverre's Les Fêtes Chinoises in London on the eve of the Seven Years' War. However, Stravinsky's early ballet scores are now widely considered masterpieces of the genre.[27]

Film of a performance

editDiaghilev always maintained that no camera could ever do justice to the artistry of his dancers, and it was long believed there was no film legacy of the Ballets Russes. However, in 2011 a 30-second newsreel film of a performance in Montreux, Switzerland, in June 1928 came to light. The ballet was Les Sylphides and the lead dancer was identified as Serge Lifar.[28]

Centennial exhibitions and celebrations

editParis, 2008: In September 2008, on the eve of the 100th anniversary of the creation of the Ballets Russes, Sotheby's announced the staging of an exceptional exhibition of works lent mainly by French, British and Russian private collectors, museums and foundations. Some 150 paintings, designs, costumes, theatre decors, drawings, sculptures, photographs, manuscripts, and programs were exhibited in Paris, retracing the key moments in the history of the Ballets Russes. On display were costumes designed by André Derain (La Boutique fantasque, 1919) and Henri Matisse (Le chant du rossignol, 1920), and Léon Bakst.

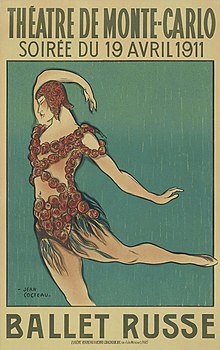

Posters recalling the surge of creativity that surrounded the Ballets Russes included Pablo Picasso's iconic image of the Chinese Conjuror for the audacious production of Parade and Jean Cocteau's poster for Le Spectre de la rose. Costumes and stage designs presented included works by Alexander Benois, for Le Pavillon d'Armide and Petrushka; Léon Bakst, for La Péri and Le Dieu bleu; Mikhail Larionov, for Le Soleil à Minuit; and Natalia Goncharova, for The Firebird (1925 version). The exhibition also included important contemporary artists, whose works reflected the visual heritage of the Ballets Russes – notably an installation made of colorfully painted paper by the renowned Belgian artist Isabelle de Borchgrave, and items from the Imperial Porcelain Factory in St. Petersburg.[29]

Monte-Carlo, 2009: In May, in Monaco, two postage stamps "Centenary of Ballets Russians of Diaghilev" went out, created by Georgy Shishkin.

London, 2010–11: London's Victoria and Albert Museum presented a special exhibition entitled Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929 at the V&A South Kensington between 5 September 2010 and 9 January 2011.

Canberra, 2010–11: An exhibition of the company's costumes held by the National Gallery of Australia was held from 10 December 2010 – 1 May 2011 at the Gallery in Canberra. Entitled Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume, it included 150 costumes and accessories from 34 productions from 1909 to 1939; one third of the costumes had not been seen since they were last worn on stage. Along with costumes by Natalia Goncharova, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, André Derain, Georges Braque, André Masson and Giorgio de Chirico, the exhibition also featured photographs, film, music and artists’ drawings.[30]

Washington, DC, 2013: Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909–1929: When Art Danced with Music. National Gallery of Art, East Building Mezzanine. 12 May— 2 September 2013. Organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Art, Washington.Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music

Stockholm, 2014–2015: Sleeping Beauties – Dreams and Costumes. The Dance Museum in Stockholm owns about 250 original costumes from the Ballets Russes, in this exhibition about fifty of them are shown. (www.dansmuseet.se)

See also

editReferences

edit- Notes

- ^ Garafola 1998, p. vii.

- ^ "Diaghilev's Golden Age of the Ballets Russes dazzles London with V&A display". Culture24. 2011-01-09. Retrieved 2013-05-08.

- ^ "Singer, Winnaretta (1865–1943) | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ a b Garafola 1998, p. 150.

- ^ Garafola 1998, p. 438, n. 7.

- ^ Garafola 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Morrison, Simon. "The 'World of Art' and Music," in [Mir Iskusstva]: Russia's Age of Elegance. Palace Editions. Omaha, Minneapolis, and Princeton, 2005. p. 38.

- ^ Guroff, Greg. "Introduction" in [Mir Iskusstva]: Russia's Age of Elegance. Palace Editions. Omaha, Minneapolis, and Princeton, 2005. p. 14.

- ^ Amanda. "Ballets Russes", The Age (17 July 2005)

- ^ Homans, Jennifer. "René Blum: Life of a Dance Master," New York Times (July 8, 2011).

- ^ a b c "Les Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo". The Oxford Dictionary of Dance. 2004. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ Tennant, Victoria (2014). Irina Baronova and the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. University of Chicago Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-226-16716-9. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ "Fortune Gallo Ballet Russe business letters". New York Library Archives. Fortune Gallo. Retrieved 15 June 2024.

- ^ "Diaghileff Ballet Russ Arrives". Musical America. 24: 33. September 23, 1916.

- ^ "They Look Pretty, Too". Los Angeles Times. December 16, 1916. p. 15. Retrieved April 10, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Banni-Viñas, Vanessa (2013). "Correcting a Ballerina's Story: The Truth Behind Makletzova v. Diaghileff". American Journal of Legal History. 53 (3): 353–361. doi:10.1093/ajlh/53.3.353.

- ^ Xenia P. Makletzova v. Sergei Diaghileff, 227 Mass. 100 (March 13, 1917 — May 25, 1917).

- ^ "Ruth Page - Early Architect of the American Ballet a biographical essay by Joellen A. Meglin on www.danceheritage.org" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-09-16. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ^ "Ruth Page's Obituary in The New York Times 9 April 1991 on www.nytimes.com". The New York Times.

- ^ "archives.nypl.org -- Ruth Page collection". archives.nypl.org.

- ^ Walsh (2000), p. 180.

- ^ "Leonide Massine". American Ballet Theatre. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- ^ Horowitz, Joseph. Artists in Exile: How Refugees from Twentieth-Century War and Revolution Transformed the American Performing Arts, New York: Harper Collins, 2008.

- ^ Albert, Jane (2010-12-11). "Inside the dress circle". The Sydney Morning Herald, "Spectrum" section. p. 2.

- ^ pritchard, jane (2010). Diaghilev and the golden age of the ballet russes. V&A Publishing. p. 104.

- ^ Buckle, Richard. Diaghilev. Weidenfeld and Nicolson, London, 1979.

- ^ Thomas Kelly (1999). "Igor Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring"". Washington D.C.: National Public Radio.

- ^ "Ballets Russes brought back to life on film" by Maev Kennedy, The Guardian, 1 February 2011. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ^ "Dancing into Glory: The Golden Age of the Ballets Russes". Ballets-Russes.com. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Bell, Robert, ed. (2010). Ballets Russes: the art of costume. Thames & Hudson UK and University of Washington Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-642-54157-4.

- Sources

- Garafola, Lynn (1998). Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. New York: Da Capo Press.

Further reading

edit- Anderson, Jack (1992). Ballet and Modern Dance: A Concise History. New Jersey: Princeton Book Company.

- Anderson, Margot, et al. Creative Australia and the Ballets Russes. Published in conjunction with the Exhibition, Arts Centre, Melbourne 2009. ISBN 978 0 9802958 1 8

- Berggruen, Olivier. The Writing of Art (London: Pushkin Press, 2011)

- Bell, Robert. Ballets Russes: The Art of Costume. National Gallery of Australia, 2011

- Christofis, Lee (June 2009). "The Ballets Russes in Australia 1936–1940" (PDF). The National Library Magazine. 1 (2): 21–23. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Clarke, Mary, and Clement Crisp. Design for Ballet. Studio Vista, 1978.

- Garafola, Lynn (1999). The Ballet Russe and its World. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Papanikolaou, Eftychia (March 2008). "The Art of the Ballets Russes Captured: Reconstructed Ballet Performances on Video". Music Library Association Notes. 64 (3): 564–585.

- Purvis, Alston (2009). The Ballets Russes and the Art of Design. New York: The Monacelli Press.

- Shead, Richard. Ballets Russes. Wellfleet Press, 1989.

- Gosudarstvennyĭ russkiĭ muzeĭ; Foundation for International Arts and Education; Joslyn Art Museum; Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum; Princeton University Art Museum (2005). Mir Iskusstva: Russia's Age of Elegance. St. Petersburg, Russia; Omaha, Nebraska; Minneapolis, Minnesote; Princeton, New Jersey: Palace Editions. ISBN 9780967845135. OCLC 60593691.

External links

edit- Ballets Russes

- The History of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes 1909–1929[usurped]

- Ballet Russe Cultural Partnership website

- Pathé newsreel extract of Les Sylphides by Ballets Russes, featuring the dancer Serge Lifar. Festival 'Fetes de Narcisses' in Montreux, Switzerland; June 1928.

- Ballets Russes de Serge Diaghilev at the Library of Congress: digital exhibition

- Ballets Russes, 1928, concert program, Library of Congress

- Eugene Olshansky Production Photographs at Newberry Library

- Ballets Russes Centennial and other exhibitions

- From Russia with love: costumes from the Ballets Russes, 1909–1933, an online exhibition featuring material from the collection of the National Gallery of Australia

- Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, 1909–1929: 20 Years That Changed The World of Art Online Exhibition, Houghton Library, Harvard University

- « Centenary of Ballets Russians of Diaghilev »

- Serge Diaghilev and His World: A Centennial Celebration of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, 1909–1929 Library of Congress

- Successor companies

- The Ballets Russes in Australia Archived 2016-04-03 at the Wayback Machine, Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo materials held in the Performing Arts Collection Archived 2012-11-03 at the Wayback Machine, at Arts Centre Melbourne