Badr al-Din Lu'lu' (Arabic: بَدْر الدِّين لُؤْلُؤ) (c. 1178-1259) (the name Lu'Lu' means 'The Pearl', indicative of his servile origins) was successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, where he governed in variety of capacities from 1234 to 1259 following the death of Nasir ad-Din Mahmud. He was the founder of the short-lived Luluid dynasty.[3] Originally a slave of the Zengid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I, he was the first Middle-Eastern mamluk to transcend servitude and become an emir in his own right, founding the dynasty of the Lu'lu'id emirs (1234-1262), and anticipating the rise of the Bahri Mamluks of the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt by twenty years (but postdating the rise of the Mamluk dynasty in India). He preserved control of al-Jazira through a series of tactical submissions to larger neighboring powers, at various times recognizing Ayyubid, Rûmi Seljuq, and Mongol overlords. His surrender to the Mongols after 1243 temporarily spared Mosul the destruction experienced by other settlements in Mesopotamia.

| Badr al-Din Lu'lu' بَدْر الدِّين لُؤْلُؤ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

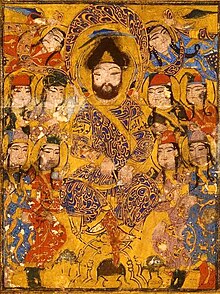

Probable portrait of Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. Manuscript illustration from the Kitāb al-Aghānī of Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani (Feyzullah Library No. 1566, Istanbul). He is wearing a Turkic dress, and is identified by his name "Badr al-Din Lu'lu'" on the țirāz bands | |||||

| Zengid dynasty Governor of Mosul | |||||

| Atabeg | 1211-1234 | ||||

| Emir of Mosul | |||||

| Rule | 1234 – 1259 | ||||

| Predecessor | Nasir ad-Din Mahmud | ||||

| Born | c. 1178 | ||||

| Died | 1259 (aged 81) | ||||

| |||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Rise to power as Zengid governor of Mosul (1211-1234)

editLu'lu' was an Armenian convert to Islam,[4] and a freed slave in the household of the Zangid ruler Nur al-Din Arslan Shah I.[5] Recognized for his abilities as an administrator, he rose to the rank of atabeg and, after 1211, was appointed as atabeg for the successive child-rulers of Mosul, Nur al-Din Arslan Shah II and his younger brother, Nasir al-Din Mahmud. Both rulers were grandsons of Gökböri, Emir of Erbil, and this probably accounts for the animosity between him and Lu'lu'. In 1226 Gökböri, in alliance with al-Muazzam of Damascus, attacked Mosul. As a result of this military pressure, Lu'lu' was forced to make a submission to al-Muazzam. Nasir al-Din Mahmud was the last Zengid ruler of Mosul, he disappears from the records soon after Gökböri's death. He was killed by Lu'lu', by strangulation or starvation, and his killer then formally began to rule in Mosul in his own right.[6][7]

Emir of Mosul (1234-1259)

editIn 1234 Lu'lu' minted the first coins in his own name, mentioning obedience to the Abbasid Caliph al-Mustansir, and his Ayyubid overlords al-Kamil and al-Ashraf.[10] Following his usurpation his new position as ruler of Mosul was recognised by the Abbasid Khalif, Al-Mustansir, who bestowed upon him the praise name al-Malik al-Rahim ("The Merciful King").[11] During his reign he sided with successive Ayyubid rulers in his disputes with other local princes. In 1237 Lu'Lu' was defeated in battle by the army of the former Khwarazmshah and his camp was thoroughly looted.

Lu'lu' was in conflict with Yezidi Kurds in his territories, he ordered the execution of one Yezidi leader, Hasan ibn Adi, and 200 of his followers in 1254.[12] The territory controlled by Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was quite extensive and reached it maximum in 1251, including Kurdistan, Sinjar, Jazirat ibn Umar, Nusaybin in the west, and the Khabur district as far as Qarqisiya on the Euphrates to the east.[13]

Lu'lu' built extensively in his domain, improving the fortifications of Mosul, the Sinjar Gate bearing his device survived into the 20th century, and constructing religious structures and caravanserais. He built the shrine of Imam Yahya (1239) and the shrine of Awn al-Din (1248).[14] The ruins of his palace complex, known as the Qara Saray (1233-1259), were visible until the 1980s.[15]

The rule of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' seems to correspond to a period of cultural bloom and religious tolerance. He sponsored the arts, including the publication of several illustrated manuscripts. He also seems to have maintained a balance between the Muslim Sunnis and Shiites, providing support for the Shiites in his primarily Muslim Sunni subjects, and seems to have been tolerant of Mosul's large Christian community. This may have been a conscious policy, which provided stability and longevity to his reign.[8]

Mongol invasion

editBadr al-Din Lu'Lu', who also had maintained good relations with the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad or the Ayyubids of Syria depending on the circumstances, supported the Mongol invasion of Mesopotamia. Following the Battle of Köse Dağ (1243), he recognized the authority of the Mongols in a way similar to the Armenian ruler Hethum I, thus avoiding destruction for his city of Mosul.[16][17] In 1246, he was summoned to the kuriltai for the accession of the new Mongol ruler Güyük Khan, to which he sent envoys who participated to the ceremonies in Karakorum with other western vassals of the Mongols such as Hethum I of Armenian Cilicia, David VI and David VII of Georgia, the later Seljuk Rums Sultan Kilij Arslan IV,[18] or Manuel I of Trebizond, the Sultan of Erzurum and the Grand Prince of Russia Yaroslav II of Vladimir.[18][19] Again in 1253, Muslim rulers presented their submission to Möngke in Karakorum, such as the Ayyubid ruler of Mayyafariqin Al-Kamil Muhammad, who went in person and encountered there envoys from Mosul (envoys of Badr al'Din Lu'lu') and Mardin (Artuqids) offering their submission.[20] Badr al'Din Lu'lu' acknowledged Mongol overlordship on his coinage in 1254.[21][22]

Badr al-Din Lu'lu' brought his assistance to Mongol troops as they converged for the 1258 Siege of Baghdad: Baiju's troops moved south through Mosul, and Badr al-Din Lu'lu' supplied provisions and weapons to the Mongol troops, and built a bridge of boats for their army to cross the Tigris.[23]

Badr al-Din helped the Khan in his following campaigns in Syria. During the final stages of the Mongol invasion of Mesopotamia, and following the Siege of Baghdad in 1258, the 80 years old Badr al-Din went in person to Meraga to reaffirm his submission to the Mongol invader Hulagu, together with the Seljuk Rums Sultans Kaykaus II and Kilij Arslan IV, and al-Azziz, son of the Ayyubid ruler of Aleppo an-Nasir Yusuf.[25][26] For his Syrian campaign, Hulegu asked Badr ad-Dīn Lu'Lu' to send him his son Al-Salih, who was put in charge of the siege of Amid (modern Diyarbakır), while Hulegu campaigned at the head of an army of 120,000 men, including Turkish, Georgian, and Armenian contingents (numbering 12 000 cavalrymen and 40 000 infantrymen for the latter), continuing to Edessa and Antioch.[27][28]

Mosul was spared destruction, but Badr al-Din died shortly thereafter in 1259.[25] Badr al-Din's son Isma'il ibn Lu'lu' (1259-1262) continued in his father's steps. In 1260, he supported the Mongol troops of Hulagu in the Siege of Mayyāfāriqīn, which was defended by its last Ayyubid ruler Al-Kamil Muhammad.[29]

But after the Mongol defeat in the Battle of Ain Jalut (1260) against the Mamluks, Isma'il sided with the latter and revolted against the Mongols.[30] Hulagu then besieged the city of Mosul for nine months, and utterly destroyed it in 1262.[25][31][32]

Family

edit- Al-Salih Isma'il ibn Lu'lu', the son of Badr al-Din Lu'lu, ruled Mosul for only three years (1259 - 1262) before his city was lost to the Mongols.[33] Through Mongol intercession, he was married in 1258 to a daughter of the last ruler of the Khwarizmian Empire Jalal al-Din, who had been raised at the Mongol court in Karakorum since her capture in 1231 at the age of two.[34]

- A daughter of Lu'lu' was set to marry Aybak, as his second wife after Shajar al-Durr. However, Aybak was killed before the marriage could take place.

Contemporary craftsmanship

editMosul under Badr al-Din Lu'lu' was characterized by fine crafstmanship, particularly in the areas of woodworking and metalworking, with the production of some of the best inlaid metalworks of the period.[35] Lu'Lu' personally supported the production of inlaid metal ewers, and several examples have remained to this day.[14] The Spanish Muslim traveller Ibn Said reported in 1250:

Mosul … there are many crafts in this city, especially inlaid-brass vessels, which are exported (and presented) to rulers, as are the silken garments woven there

To a large extent, the flourishing of metalworks under Badr al-Din Lu'lu' and in other parts of the Near-East is attributed to the western exodus of artists from Khurasan as a consequence of the Mongol conquests.[36] Still, some objects are known to date back to as early as 1220, thus essentially predating Mongol invasions, which suggest some production may have pre-existed locally.[37]

The Blacas ewer is generally attributed to Badr al-Din Lu'lu'.

-

Coin of Badr al Din Lu'lu', Mosul, 1210–1259. The central legend starts with "Lu'Lu'" at the top (Arabic: لُؤْلُؤ). British Museum

-

Wooden door of the Great Mosque of Amadiya (13th century); the inscription mentions sultan Badr-addin Ibn Lulu Ibn Abdullah, the happy sultan, and the merciful king.

-

Homberg ewer, by Ahmad al-Dhaki al-Mawsili. Inlaid Brass with Christian Iconography. probably Mosul, dated 1242–43.[38]

-

Inlaid brass tray of Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. Mosul, 13th cen. V&A.[39]

-

Cylindrical lidded box with an Arabic inscription recording its manufacture for the ruler of Mosul, Badr al-Din Lu'lu

-

Mausoleum of Yahya Abu al-Qasim, built in Mosul by Lu'Lu' in 1239.[14]

-

Wooden cenotaph, Jazira, probably Mosul, ca, 1237, David Collection.[40]

Literature

editThe Book of Songs (1218-1219)

editDuring his period as governor for the Zengid dynasty, Lu'lu' appears prominently in the 1218-1219 edition the Kitāb al-aghānī ("Book of Songs"), probably made in Mosul. The whole edition consists in 20 volumes, four of them now being in the National Library in Cairo (II, IV, XI, XIII), two more in the Feyzullah Libray, Istanbul (XVII, XIX), and the last one in the Royal Library, Copenhagen.[43] and had several miniatures, only six of which have remained.[44]

In the miniatures, Lu'lu' wears the Turkic military furred hat, the Sharbush (Harbush).[44][45] He also wears a gold brocaded Turkic tunic (qabā` turki), with țirāz arm bands on which his name is clearly inscribed.[46] He has red leather boots with stamped gold decorations.[47] Most of his attendants wear the Turkic dress, with Turkic coat, boots and headress.[47]

-

Lu'lu' with musicians and male attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol IV. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[44]

-

Lu'lu' with two senior figures, possibly a turbaned Christian bishop and a Turkish military leader with a fur-trimmed hat. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XI. Cairo, Egyptian National Library, Ms Farsi 579.[44]

-

Lu'lu' on horse with attendants. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XIX. Istanbul, Millet Library, Ms Feyzullah Efendi 1565.[44]

-

Lu'lu' on galloping horse. Kitāb al-aghānī, Mosul, 1218-1219. Vol XX. Royal Library, Copenhagen, Denmark, No. 168.[48]

Jacobite-Syrian Lectionary of the Gospels (c.1220)

editSeveral important Christian manuscripts were also created in Mosul during the period of the rule Badr al-Din Lu'lu'. One of them, the Jacobite-Syrian Lectionary of the Gospels, was created at the Mar Mattai Monastery 20 kilometers northeast of the city of Mosul, c.1220 (Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559).[49] This Gospel, with its depiction of many military figures in armour, is considered as a useful reference of the military technologies of classical Islam during the period.[50]

-

Detail of f.139r, Crucifixion. Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559.

-

Detail of f.18r, Massacre of the Innocents. Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559.

-

Detail of f.29v, Beheading of John the Baptist. Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559.

-

Detail of f.28r, John the Baptist preaching. Vatican Library, Ms. Syr. 559.

The Book of Theriac (1225-1250)

editA mid-13th century edition (second quarter of the 13th century, i.e. 1225-1250) of the manuscript Kitâb al-Diryâq, attributed to Mosul, is known from the Nationalbibliotek in Vienna (A.F. 10).[54] Although there is no mention of a dedication in this edition, the courtly paintings are quite similar to those of the court of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' in the Kitab al-Aghani (1218-1219), and may be related to this ruler.[55][56]

-

Turkoman soldiers (detail). Book of Antidotes of Pseudo-Gallen. Probably northern Iraq (Mosul). Mid 13th century.[57]

-

Ancient physicians, Kitab al-diryaq, Vienna AF 10

-

Kitab al-diryaq, Vienna AF 10

References

edit- ^ Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus. Austrian Academy of Science Press. p. 231 & 246 Fig.10.

- ^ Fuess, Albrecht (2018). "Sultans with Horns: The Political Significance of Headgear in the Mamluk Empire (MSR XII.2, 2008)" (PDF). Mamlūk Studies Review. 12 (2): 76, 84, Fig.3 and Fig. 6. doi:10.6082/M100007Z.

- ^ "Collections Online British Museum". www.britishmuseum.org.

- ^ Islamic art and architecture 650-1250 By Richard Ettinghausen, Oleg Grabar, Marilyn Jenkins, pg, 134

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 61.

- ^ Gibb, pp. 700-701

- ^ Patton, pp.152-155

- ^ a b Snelders, Bas (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area. Peeters. pp. Extract. ISBN 978-90-429-2386-7.

Patton argues that in addition to Badr al-Din Lu'lus ordering and sponsoring the foundation of numerous social and religious institutions in Mosul, his energetic patronage of the arts was probably part of a conscious policy aimed at securing the loyalty of the city's population and ensuring that they would not turn their backs on him in favour of one of his opponents. This egalitarian treatment of the Muslim Sunnis and Shiis should certainly beseen in this light, but also his comparatively tolerant attitude towards Mosul's large Christian community. As Patton argues, 'Lu'lus skill at maintaining the support of all groups while especially favouring none is a remarkable achievement which explains not only the duration of his reign, but probably the great efflorescence of the arts in his reign as well. After the death of Badr al-Din Lu'lu' in 1259, however, the prosperous period and cultural bloom in the Mosul area soon came to an end.

- ^ S&S Type 68; Album 1874.1

- ^ S&S Type 68; Album 1874.1

- ^ O'Kane, Bernard (2012). "Text and Paintings in the Al-Wāsiṭī "Maqāmāt"". Ars Orientalis. 42: 43. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 43489763.

- ^ Kreyenbroek and Rashow, p. 4

- ^ a b Snelders, Bas (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area. Peeters. pp. Extract. ISBN 978-90-429-2386-7.

At the height of his rule, around the year 1251, realm of Lu'lu' included Kurdistan, Sinjar, Jazirat ibn Umar, Nasibin or Nisibis (Nusaybin), and the Khabur district as far as Qarqisiya on the Euphrates.

- ^ a b c d Snelders, Bas (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area. Peeters. pp. Extract. ISBN 978-90-429-2386-7.

- ^ Bloom and Blair (eds.), p. 249

- ^ Snelders, Bas (2010). Identity and Christian-Muslim Interaction: Medieval Art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area. Peeters. pp. Extract. ISBN 978-90-429-2386-7.

He cultivated close relationships with the Abbasid Caliph in Baghdad, the Ayyubids of Syria, and the Mongols, respectively, shifting his loyalty depending on the political situation of the day. In 1245, he recognized the authority of the Mongols and supported their invasion of Mesopotamia, thus saving Mosul from being sacked by Mongol invaders, a fate suffered by so many cities at the time.

- ^ Pubblici, Lorenzo (2021). Mongol Caucasia. Invasions, conquest, and government of a frontier region in thirteenth-century Eurasia (1204-1295). Brill. p. 145. ISBN 978-90-04-50355-7.

1243 (...) With much astuteness, Hethum I, who did not wait for the Mongols' arrival, immediately declared himself to be the subject and vassal of the noyons of Ögedei. He entered under Mongol protection and managed to exercise his sovereignty precisely as he had done until then and paid tribute to the Mongols. A similar strategy was followed by the atabeg of Mosul, who willingly accepted Mongol protection and spared the lives of its people.

- ^ a b Eastmond, Antony (2017). Tamta's World: The Life and Encounters of a Medieval Noblewoman from the Middle East to Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. p. 348, 381. doi:10.1017/9781316711774. ISBN 9781316711774.

Toregene Khatun, the de facto ruler of Mongolia during much of Tamta's captivity, was the most formidable of these women. After the death of her husband, Ogodei Khan, in 1241, she had assumed rule until a successor was chosen. As her favoured son, Guyuk, was too young to succeed his father, Toregene spun out the regency for five years until he was old enough to be elected at the kuriltai that Toregene then convened (this was the kuriltai to which Hetum of Cilicia, the two Davits of Georgia, the Seljuk Sultan, Badr al-Din Luʾluʾ of Mosul and so many other vassal rulers were summoned).

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2004). Art and Identity in Thirteenth-Century Byzantium_ Hagia Sophia and the Empire of Trebizond (PDF). Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 9780754635758.

In 1246 he [Manuel] travelled to the kuriltai [great meeting] of the new khan, Guyuk, at Karakorum, as the equal of the sultan of Rum, the two kings of Georgia, the sultan of Erzurum and the emir of Aleppo, where he received a yarligh [decree] confirming his rulership.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. p. 541. ISBN 978-0-415-96690-0.

The Ayyubid ruler of Mayyafariqin, al-Kamil Muhammad, arrived at Mo ̈ngke's court in 1253, made his submission, and found there Muslim princes from Mosul and Mardin. It is clear, then, that years before Hulegu's arrival in the area, the majority of Muslim princes in Iraq, Jazira, and Syria had made some type of submission to the Mongols and that at least some were paying tribute.

- ^ Bosworth, C. E. (1 June 2019). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual. Edinburg University Press. p. 193. doi:10.1515/9781474464628. ISBN 978-1-4744-6462-8. S2CID 249526562.

Lu'lu' and the local Ayyubid princes became tributary to the Mongols, and Lu'lu' 's later rule was increasingly subordinate to them, whose overlordship he explicitly acknowledged on his coins in 652/1254.

- ^ Venegoni 2003 "Badr ad-Dīn Lu'Lu atabeg of Mosul who had allowed coins to be minted in Hülägüs honour before his arrival"

- ^ Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan, D. (2011). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). Leiden ; Boston: Brill. p. 129. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

Since Baghdad shared a common border with Mosul and knowing that Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu', the atabeg of Mosul, who had already supported the Mongols, would assist him, Baiju came from Anatolia to the west bank of the Tigris by the Mosul road. (...) Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu' was obliged to supply provisions, weapons and a bridge of boats over which Baiju 's army crossed the Tigris (Patton, 1991:60).

- ^ "American Numismatic Society. Gold dinar of Badr al-Din Lu'lu'/ Möngke Khan, al-Mawsil, 657 H. 1962.126.11". Stanford.edu.

- ^ a b c Bretschneider, E. (5 November 2013). Mediaeval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century: Volume II. Routledge. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-136-38056-3.

- ^ Runciman (1954). A History Of The Crusades Vol-iii (1954). Penguin Book. pp. 304–305.

- ^ Venegoni 2003 "Before his start of the concluding part of his campaign, Hülägü asked his vassal Badr ad- Dīn Lu'Lu', from Herat to send to the battlefield his son Ssalih. The Atabeg obeyed Hülägü's order, sending him his son. This fact gave Hülägü great joy and rewarded Ssalih by giving him the hand of the daughter of the last great sultan of Chorezm. (...) At the time Hülägü's massive invasion force is said to have numbered 120 000 men. It included Turkish, Georgian and Armenian contingents and once again marched in four separate divisions. The Armenian military contingent for the conquest totalled 12 000 cavalrymen and 40 000 infantrymen. (...) Badr ad-Dīn Lu' Lu's son Ssalih was sent to besiege the town of Amid, known today as Dyarbakir."

- ^ Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan, D. (2011). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). Leiden ; Boston: Brill. p. 137. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

Hűlegű called for the Cilician Armenians and set out for Syria. He personally commanded the centre, placing commanders Baiju and Shiktűr on the right flank and other amirs on the left. The army passed through Ala-Tagh, Akhlā and the Hakkārī mountains into Diyārbakr or Amida, which was captured by the son of Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu'.

- ^ Bai︠a︡rsaĭkhan, D. (2011). The Mongols and the Armenians (1220-1335). Leiden ; Boston: Brill. p. 133-134. ISBN 978-90-04-18635-4.

The Ayyubid ruler of Mayyāfāriqīn and Amida, Al-Kamil Muhammad, had broken his vow to Hűlegű to supply troops for the siege of Baghdad . (...) Hűlegű sent support, in the form of Mongol-Christian troops commanded by a certain Chaghatai and the Armenian Prince Pŕosh Khaghbakian. The Governor of Mosul, Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu', who was in conflict with al-Kāmil Muhammad, sent a supporting force to the Mongols commanded by his son, along with siege engineers to Mayyāfāriqīn.

- ^ Wu, Pai-nan Rashid (1974). The Fall of Baghdad and the Mongol Rule in Al-Iraq, 1258-1335. University of Utah. p. 91.

- ^ Bloom and Blair (eds.), pp. 249, 499

- ^ Rice 1950, p. 627.

- ^ Spengler and Sayles, p. 140

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2017). Tamta's World: The Life and Encounters of a Medieval Noblewoman from the Middle East to Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. p. 344. doi:10.1017/9781316711774. ISBN 9781316711774.

Similarly, when Muhammad's son Jalal al-Din was defeated in 1231, his harem was also transferred to Mongolia. One of his daughters, aged two when she was captured, was to remain in Karakorum for a quarter of a century, until she was finally returned to become the bride of al-Salih Ismaʿil, the son of the atabeg Badr al-Din Luʾluʾ, in 1258. By then her Islamic roots had been overlaid with a veneer of Mongolian upbringing. When she arrived in Mosul she was wearing Mongol costume, and received 'a dowry after the Mongol custom', but she was married in accordance with Islamic rites.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 265 ff.

- ^ Kadoi, Yuka (31 July 2019). Islamic Chinoiserie: The Art of Mongol Iran. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 79–80. ISBN 978-1-4744-6967-8.

- ^ Brend, Barbara (1991). Islamic Art. Harvard University Press. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-674-46866-5.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 265.

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 62.

- ^ Canby et al. 2016, p. 296, Fig.193.

- ^ "Ewer The Walters Art Museum". Online Collection of the Walters Art Museum.

- ^ Rice, D. S. (1953). "The Aghani Miniatures and Religious Painting in Islam". The Burlington Magazine. 95 (601): 128–135.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ a b c d e Rice, D. S. (1953). "The Aghānī Miniatures and Religious Painting in Islam". The Burlington Magazine. 95 (601): 128–135. ISSN 0007-6287. JSTOR 871101.

- ^ Hillenbrand, Robert (1999). Islamic art and architecture. London : Thames and Hudson. p. 127, Figure 100. ISBN 978-0-500-20305-7.

- ^ Badr al din Lu'lu' name of his tiraz bands

Flood, Finbarr Barry (2017). A Turk in the Dukhang? Comparative Perspectives on Elite Dress in Medieval Ladakh and the Caucasus. Austrian Academy of Science Press. p. 231 & 246 Fig.10. - ^ a b Yedida Kalfon Stillman, Norman A. Stillman (2003). Arab Dress: A Short History : from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. p. 67. ISBN 9789004113732.

Fig.23: Frontispiece of Kitab al-Aghani from Iraq, ca. 1218/19 depicting the enthroned atabeg Badr ai-DIn Lu'lu' 'Abd Allah wearing a gold brocaded (Zarkash), lined qabā` turki with gold Tira'z armbands on which his name is clearly inscribed. His boots are of red leather with gold, probably stamped, vegetal decoration. On his head is a fur-trimmed sharbush. Most of his attendants wear Turkish coats, boots, and a variety of kalawtat (Millet Kiitiiphanesi, Istanbul, Feyzullah Efendi ms 1566, folio Ib).

- ^ Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs - MetPublications - The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. 2016. p. 61.

- ^ Eastmond, Antony (2017). Tamta's World: The Life and Encounters of a Medieval Noblewoman from the Middle East to Mongolia. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781316711774. ISBN 9781316711774.

- ^ Nicolle, David (2008). Military technology of classical Islam. Edinbourg University Press. p. Vol.3, Figures 306 (A-F).

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ Yedida Kalfon Stillman, Norman A. Stillman (2003). Arab Dress: A Short History : from the Dawn of Islam to Modern Times. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill. pp. Fig.19. ISBN 9789004113732.

Fig.19: 19. Frontispiece of a mid-13th-century manuscript, probably from Mosul of the Kitāb al-Diryāq of Pseudo-Galen showing an informal court scene in the center with a seated Turkish ruler (on left) wearing a fur-trimmed, patterned qaba' maftulJ, with elbow-length tiraz sleeves and on his head a sharbilsh. Most of his attendants wear aqbiya turkiyya and kalawta caps. Workman depicted behind the palace and riders in the lower register wear the brimmed hat with conical crown known as saraquj. On the saraquj of one workman is a crisscrossed colored takhftfa with a brooch or plaquette pinned in the center of the overlap. The women on camels in the lower righthand corner wear a sac-like head veil kept in place by a cloth 'isaba (Nationalbibliothek, Vienna, ms A. F. 10, fol. 1).

- ^ Pancaroǧlu, Oya (2001). "Socializing Medicine: Illustrations of the Kitāb al-diryāq". Muqarnas. 18: 155–172. doi:10.2307/1523306. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 1523306.

- ^ Pancaroǧlu, Oya (2001). "Socializing Medicine: Illustrations of the Kitāb al-diryāq". Muqarnas. 18: 169. doi:10.2307/1523306. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 1523306.

- ^ "Kitab al-diryaq (Book of Antidotes) - Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Islamic Art Museum.

It may potentially be related to the courtly milieu of Badr ad-Din Lu'lu' (died 1259), successor to the Zengid emirs of Mosul, who is known to have commissioned other manuscripts.

- ^ Ettinghausen, Richard (1977). Arab painting. New York : Rizzoli. p. 91, 92, 162 commentary. ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

In the painting the facial cast of these Turks is obviously reflected, and so are the special fashions and accoutrements they favored. (p.162, commentary on image p.91)

Bibliography

edit- Bloom, J.M. and Blair, S.S. (eds.) (2009) The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture, Volume I: Abarquh to Dawlat Qatar, Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Canby, Sheila R.; Beyazit, Deniz; Rugiadi, Martina; Peacock, A. C. S. (27 April 2016). Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-58839-589-4.

- Rice, D. S. (October 1950). "The Brasses of Badr al-Dīn Lu'lu'". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 13 (3): 627–634. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00140042.

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1969) [1962]. "The Aiyubids". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Wolff, Robert Lee; Hazard, Harry W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Later Crusades, 1189–1311 (Second ed.). Madison, Milwaukee, and London: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 693–714. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

- Kreyenbroek, P.G. and Rashow, K.J. (2005) God and Sheik Adi are Perfect, Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden

- Patton, D. (1988) Ibn al-Sāʿi's Account of the Last of the Zangids, Zeitschrift der Deutschen, Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 138, No. 1, pp. 148–158, Harrassowitz Verlag Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43377738 [1]

- Spengler, W.F. and Sayles, W.G. (1992) Turkoman Figural Bronze Coins and Their Iconography: The Artuquids, Clio's Cabinet, Lodi

- Venegoni, L. (2003). Transoxiana Webfestschrift Series I, Webfestschrift Marshak 2003. Eran ud Aneran: studies presented to Boris Il'ic Marsak on the occasion of his 70th birthday (1. ed.). Venezia: Cafoscarina. ISBN 8875431051.

External links

edit- Imam Awn al-Din Mashhad (Mosul) [2] Archived 2008-05-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Imam Yahya ibn al-Qasim Mashhad (Mosul) [3] Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Sittna Zaynab Mausoleum (Sinjar) [4] Archived 2010-12-14 at the Wayback Machine