Bacup (/ˈbeɪkəp/ BAY-kəp,[1] /ˈbeɪkʊp/) is a town in the Rossendale Borough in Lancashire, England, in the South Pennines close to Lancashire's boundaries with West Yorkshire and Greater Manchester. The town is in the Rossendale Valley and the upper Irwell Valley, 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Rawtenstall, 6 miles (9.7 km) north of Rochdale, and 7 miles (11 km) south of Burnley. At the 2011 Census, Bacup had a population of 13,323.[2]

| Bacup | |

|---|---|

Yorkshire Street, Bacup | |

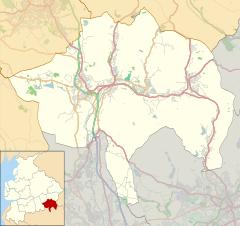

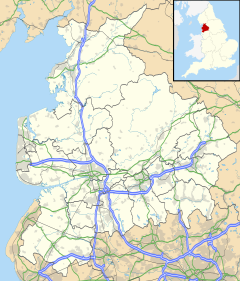

Location within Lancashire | |

| Population | 13,323 (2011 Census) |

| OS grid reference | SD868231 |

| • London | 175 mi (282 km) SSE |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BACUP |

| Postcode district | OL13 |

| Dialling code | 01706 |

| Police | Lancashire |

| Fire | Lancashire |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Bacup emerged as a settlement following the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain in the Early Middle Ages. For centuries, it was a small and obscure centre of domestic flannel and woollen cloth production, and many of the original weavers' cottages survive today as listed buildings. Following the Industrial Revolution, Bacup became a mill town, growing up around the now covered over bridge crossing the River Irwell and the north–south / east-west crossroad at its centre. During that time its landscape became dominated by distinctive and large rectangular woollen and cotton mills. Bacup received a charter of incorporation in 1882, giving it municipal borough status and its own elected town government, consisting of a mayor, aldermen and councillors to oversee local affairs.

In 1974, Bacup became part of the borough of Rossendale.[3] Bacup's historic character, culture and festivities have encouraged the town to be seen as one of the best preserved mill towns in England.[4][5] English Heritage has proclaimed Bacup town centre as a designated protected area for its special architectural qualities.

History

editThe name Bacup is derived from the Old English fūlbæchop. The Oxford Dictionary of British Place Names translates this as "muddy valley by a ridge"; the fūl- element, which meant "foul" or "muddy" was used in the earliest known reference to the area, in a charter by Robert de Lacey, around the year 1200, as used in the Middle English spelling fulebachope.[6] The prefix ful- was dropped from the toponym.[6] The -bæchop element is less clear, possibly meaning "ridge valley",[6] or else "back valley" referring to the locale's position at the back part of the Irwell Valley.[7][8]

Bacup and its hinterland has provided archeological evidence of human activity in the area during the Neolithic.[9][10] Anglo-Saxons settled in the Early Middle Ages. It has been claimed that in the 10th century the Anglo-Saxons battled against Gaels and Norsemen at Broadclough,[11] a village to the north of Bacup.[12][13][14] From the medieval period in this area, the River Irwell separated the ancient parishes of Whalley and Rochdale (in the hundreds of Blackburn and Salford respectively). The settlement developed mainly in the Whalley township of Newchurch but extending into Rochdale's Spotland.[15]

The geology and topography of the village lent itself to urbanisation and domestic industries; primitive weavers' cottages, coal pits and stone quarries were propelled by Bacup's natural supply of water power in the Early Modern period. The adoption of the factory system, which developed into the Industrial Revolution, enabled the transformation of Bacup from a small rural village into a mill town, populated by an influx of families attracted by Bacup's cotton mills, civic amenities and regional railway network. Locally sourced coal provided the fuel for industrial-scale quarrying, cotton spinning and shoemaking operations, stimulating the local economy. Bacup received a charter of incorporation in 1882, giving it honorific borough status and its own elected town government, consisting of a mayor, aldermen and councillors to oversee local affairs.

Bacup's boom in textile manufacture during the Industrial Revolution resulted in the town developing into a prosperous and thickly populated industrial area by early-20th century. But the Great Depression and the ensuing deindustrialisation of the United Kingdom largely eliminated Bacup's textile processing sector and economic prosperity.

Bacup followed the regional and national trend of deindustrialisation during the early and mid-20th century; a process exacerbated by the closure of Bacup railway station in 1966. Bacup also experienced population decline; from 22,000 at the time of the United Kingdom Census 1911, to 15,000 at the United Kingdom Census 1971. Much of Bacup's infrastructure became derelict owing to urban decay, despite regeneration schemes and government funding. Shops became empty and some deteriorated. The houses along the main roads endured as the original terraces from Bacup's industrial age, but behind these, on the hillsides, are several council estates.[3][16][17]

Records in 2005 show Bacup to have some of the lowest crime levels in the county,[18] and the relative small change to Bacup's infrastructure and appearance has given the town a "historic character and distinctive sense of place".[3] In 2007, the murder of Sophie Lancaster attracted media attention to the town and highlighted its urban blight and lack of amenities and regeneration.[16][19][20]

Regeneration

editIn 2013 it was announced that Rossendale Borough Council was successful in securing £2m funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund for a 5-year regeneration project, to be delivered by the Bacup Townscape Heritage Initiative (THI). The project focuses on the redevelopment and restoration of Bacup's unique built and cultural heritage whilst providing training in traditional building skills and to facilitate activities and events for local people.[21] The injection of funds has significantly contributed to growing property prices in the area[22] with the investments in the area being cited as one of the major reasons why the area is becoming increasingly attractive to people commuting to larger conurbations such as Greater Manchester.[23]

Due to the success of the Bacup THI and following public research and consultation, in 2019 the Rossendale Borough Council announced the development of the Bacup 2040 Vision and Masterplan.[24] Bacup 2040 sets out a new vision for Bacup,[25] aiming to capitalise on the gains made through the THI scheme whilst redeveloping aspects of the town to make it fit for a high-street model less reliant on retail and more suited to the needs of visitors and local residents alike. In order to realise the scheme, the council considered multiple bid options and the Bacup 2040 Vision was used as the basis of its bid for a share of the £1b Future High Street Fund.[26] The Bacup 2040 Board was established in 2019[27] and is made up of representatives from across Bacup, including local residents, business owners, community organisations, charities, councillors, council officers. The board is chaired by a local business owner[28] and has 6 sub-group committees, chaired by representatives of different community organisations,[29] reviewing the various aspects of the vision and plan.[30] The role of the board is to "inform, challenge and validate the scope and proposals for the redevelopment of Bacup."[31]

The Bacup 2040 plan for the £11.5m redevelopment of Bacup's core, including the Market Square, was reported on in February 2020 and later announced by the local council in June 2020.[32][33]

The first stages of the commencement of the Bacup 2040 work was announced in June 2020, with the £1m redevelopment of the long-time derelict Regal Building.[34]

Governance

editLying within the historic county boundaries of Lancashire since the High Middle Ages, Bacup was a chapelry linked with the parishes of Whalley and Rochdale, and divided between the townships of Newchurch and Spotland in the hundred of Blackburn.[35]

Bacup's first local authority was a Local board of health established in 1863;[36] Bacup Local Board of Health was a regulatory body responsible for standards of hygiene and sanitation in the Bacup Urban Sanitary District. The area of the sanitary authority was granted a charter of incorporation in 1882, giving it honorific borough status and its own elected town government, consisting of a mayor, aldermen and councillors to oversee local affairs.[12][14][36][37] The Municipal Borough of Bacup became a local government district of the administrative county of Lancashire under the Local Government Act 1894, meaning it shared power with the strategic Lancashire County Council.[37] The council was based at Bacup Town Hall.[38] Under the Local Government Act 1972, the Municipal Borough of Bacup was abolished, and since 1 April 1974 Bacup has formed an unparished area of Rossendale, a local government district of the non-metropolitan county of Lancashire.[37]

From 1992 until 2010, Bacup was represented in the House of Commons as part of the parliamentary constituency of Rossendale and Darwen, by Janet Anderson, a Labour Party Member of Parliament (MP).[39] Bacup had previously formed part of the Rossendale constituency. In the general election of 2010, the seat was taken by Jake Berry of the Conservative Party, and in 2024 it was taken by Andy MacNae of Labour.

Geography

editAt 53°42′14″N 2°11′56″W / 53.70389°N 2.19889°W (53.704°, −2.199°), 15 miles (24.1 km) north-northeast of Manchester, 17 miles (27.4 km) southeast of Blackburn and 26 miles (41.8 km) southwest of Bradford. Bacup stands on the western slopes of the South Pennines, amongst the upper-Irwell Valley. The River Irwell, a 39-mile (63 km) long tributary of the River Mersey, runs southwesterly through Bacup towards Rawtenstall from its source by the town's upland outskirts at Weir.[40] The Irwell is mostly culverted in central Bacup but it is open in the suburbs. In 2003 there was a proposal to use plate glass for a section of the culvert in the centre of the town however the culvert was eventually replaced with concrete.[40] Bacup is roughly 1,000 feet (305 m) above sea level;[41] the Deerplay area of Weir is 1,350 feet (411 m) above sea level;[40] Bacup town centre is 835 feet (255 m) above sea level.[12]

Bacup is surrounded by open moor and grassland on all sides with the exception of Stacksteads at the west which forms a continuous urban area with Waterfoot and Rawtenstall.[42][43] The towns of Burnley and Accrington are to the north and northwest respectively; Todmorden, Walsden and the county of West Yorkshire are to the east; Rochdale and the county of Greater Manchester are to the south; Rawtenstall, from where Bacup is governed, is to the west. Areas and suburbs of Bacup include Britannia, Broadclough, Deerplay, Dulesgate, Stacksteads and Weir.[3][12][13][35]

Bacup experiences a temperate maritime climate, like much of the British Isles, with relatively cool summers, yet harsh winters. There is regular but generally light precipitation throughout the year.

Landmarks

editThe town's parish church is dedicated to Saint John the Evangelist. Aside from just this church, Bacup has many other churches.[12][44][45] The majority of Bacup's culturally significant architecture is in the Victorian period, but there are older buildings of note are Fearns Hall (1696), Forest House (1815) and the 18th-century Stubbylee Hall.[14] The Bacup Natural History Society Museum was formed in 1878.[46]

Bacup is home to the 17 ft (5.2 m) long Elgin Street which held the record as the shortest street in the world until November 2006, when it was surpassed by Ebenezer Place, in the Scottish Highlands.[47]

Many of the town's historic buildings are set to be renewed in a £2m regeneration scheme.[48]

Transport

editBacup railway station was opened in 1852[49] by the East Lancashire Railway as the terminus of the Rossendale line. The Rochdale and Facit Railway was extended to Bacup in 1883. It rose over a summit of 967 feet (295 m) between Britannia and Shawforth. The Rochdale line closed to passenger services in 1947,[50] and the station finally closed in December 1966,[49] with the cessation of all passenger services to and from Manchester Victoria via Rawtenstall and Bury.

In June 2014 the police announced they would be monitoring the road between Weir and Bacup (which passes through Broadclough) as it has become an accident blackspot with a high number of accidents which have resulted in serious injury and even deaths.[51]

A671 Bypass proposals

editThere have been a large number of road traffic incidents on the A671 as it passes through the small hamlets of Broadclough and Weir near Bacup including fatalities. Currently police are monitoring the road[51] and there have been calls from local residents, led by County Councillor Jimmy Easton,[52] for the creation of a bypass with the suggestion of utilising elements of Bacup Old Road.

Culture and community

editThe key date in Bacup's cultural calendar is Easter Saturday, when the Britannia Coconut Dancers beat the bounds of the town via a dance procession. Britannia Coconut Dancers are an English country dance troupe from Bacup whose routines are steeped in local folk tradition. They wear distinctive costumes and have a custom of blackening their faces. The origin of the troupe is claimed to have its roots in Moorish, pagan, medieval, mining and Cornish customs.[53] The Easter Saturday procession begins annually at the Traveller's Rest Public House on the A671 road. The dancers are accompanied by members of Stacksteads Silver Band and proceed to dance their way through the streets.[53]

Bacup Museum is local history hub and exhibition centre in Bacup. The Bacup Natural History Society was formed in 1878.[54] The work of the society is carried out by a group of volunteers who have a base in the Bacup Museum which contains many domestic, military, industrial, natural history, and religious collections.[55]

Bacup has been used as a filming location for the 1980s BBC TV police drama Juliet Bravo, Hetty Wainthropp Investigates, parts of The League of Gentlemen and much of the film Girls' Night. Elements of the BBC TV drama Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit were also filmed on location in Bacup.[56] The famous 1961 British film Whistle Down the Wind starring Hayley Mills also used various parts of Bacup for filming. The comedy drama Brassic was also largely filmed in Bacup.

Media

editLocal news and television programmes are provided by BBC North West and ITV Granada. Television signals are received from the Winter Hill and local relay TV transmitters.[57][58]

Local radio stations are BBC Radio Lancashire on 95.5 FM, Heart North West on 105.4 FM, Capital Manchester and Lancashire on 107.0 FM, Greatest Hits Radio Lancashire on 96.5 FM, and Rossendale Radio, a community based radio station which broadcast to the town on 104.7 FM.[59]

The town's the local newspaper is the Lancashire Telegraph.[60]

Notable people

edit- Lawrence Heyworth (1786–1872), Member of Parliament and Radical activist

- Isaac Hoyle (1828–1911), British mill-owner and Liberal politician

- Emily Sarah Holt (1836–1893), English children's novelist

- John B. Sutcliffe (1853–1913), English-American architect

- Beatrice Webb (1858–1943), English sociologist, economist, socialist, labour historian and social reformer.[62] She lived amongst textile factory workers in Bacup in the 1880s.[63]

- Sir John Maden (1862–1920), Liberal Party politician, MP for Rossendale, 1892–1900

- Herbert Bolton (1863–1936), palaeontologist and director of the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery

- Betty Jackson (born 1949), fashion designer; her father owned a shoe factory in town.[64][65]

- Johnny Clegg (1953–2019), South African musician from the bands Juluka and Savuka

- Paul Stephenson (born 1953), Metropolitan Police Commissioner, 2009 to 2011

- Jennie McAlpine (born 1984), actress, plays Fiz Stape in Coronation Street[66]

- Sophie Lancaster (1986–2007), murder victim

- Sam Aston (born 1993), actor who plays Chesney Brown in Coronation Street

Sport

edit- Eddie Cooper (1915–1968), cricketer, right-handed batsman who played 249 first-class matches for Worcestershire

- Everton Weekes (1925–2020), cricketer, lived in Bacup and played for Bacup Cricket club between 1949 and 1958

- Marc Pugh (born 1987), association footballer with over 470 club caps[67][68]

- Matty James (born 1991), footballer for Bristol City F.C. with over 180 domestic league caps

- Reece James (born 1993), footballer for Sheffield Wednesday F.C. with over 208 domestic league caps

See also

editReferences

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Miller 1971, p. 8

- ^ "Town population 2011". Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Freethy, Ron; Willmott, Alex (24 July 2007), "Joint fight to get Bacup back on its feet", Lancashire Telegraph, lancashiretelegraph.co.uk, archived from the original on 11 June 2011, retrieved 27 October 2009

- ^ "The Bacup 2040 Vision" (PDF). Invest in Rossendale. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Let's Move to Bacup, Lancashire". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c Mills 2003, p. 28.

- ^ Fenton 2006, p. 5.

- ^ Cameron 1961, p. 182.

- ^ Historic England, "Monument No. 45228", Research records (formerly PastScape), retrieved 27 October 2009

- ^ Historic England, "Monument No. 887154", Research records (formerly PastScape), retrieved 27 October 2009

- ^ "Broadclough Dykes: Lancashire's Most Important Unresolved Archeological Site? - Bacup Business Association". Archived from the original on 22 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Manchester City Council, Helmshore Mills, spinningtheweb.org.uk, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ a b Whitworth Town Council, Town Overview, Government of the United Kingdom, archived from the original on 16 October 2015, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ a b c Rossendale Borough Council, A Brief History of Rossendale; Bacup, Government of the United Kingdom, p. 2, archived from the original on 18 March 2014, retrieved 3 September 2013

- ^ Farrer and Brownbill 1911, pp. 437–441

- ^ a b Hodkinson, Mark (3 August 2008), "United in the name of tolerance", The Observer, London, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ Tonge, Jenny (16 December 2005), "Bacup 'left to rot'", Rossendale Free Press, M.E.N. Media, archived from the original on 24 September 2012, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ Smyth, Catherine (2 December 2005), "Bacup crime levels lowest in county", Rossendale Free Press, M.E.N. Media, archived from the original on 12 November 2012, retrieved 4 January 2013

- ^ Korn, Helen, Bacup is the same as any town, thisislancashire.co.uk, archived from the original on 22 March 2014, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ Balakrishnan, Angela; agencies (29 October 2008), "Goth murderer wins shorter sentence", The Guardian, London: Guardian News and Media, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ "What is the THI Project". THI. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- ^ "Property Prices in Bacup from 2005 to 2018". House.co.uk.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Great value property in a stunning location – why we should all move to the Rossendale Valley". MEN. 22 March 2017.

- ^ "What Bacup Could Look Like In 2040". Lancs Live. 29 March 2019.

- ^ "Bacup 2040 Website".

- ^ "Bacup Share £1bn Pot of Cash To Re-Invent High Street". Lancs Live. 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Bacup 2040". Bacup THI. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Trafford Tour Gives Food For Thought For Bacup Regeneration". Rossendale News. 14 November 2019.

- ^ "About Bacup & Stacksteads Neighbourhood Forum". Bacup and Stackstead Neighbourhood Forum. Archived from the original on 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Quarter 3 2019–2020 Appendix 1 Rossendale Borough Council". Rossendale Borough Council.

- ^ "Why We Support The Bacup 2040 Vision And Masterplan". GrowTraffic. 28 May 2020.

- ^ "New Images Of £9m Bacup Market Square Redevelopment Unveiled". Lancs Live. 28 February 2020.

- ^ "11 Million Bid To Overhaul East Lancashire Town". Lancashire Telegraph. 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Former Bacup Cinema Restored And Brough Back into Use in £1m plan". Lancs Live. 15 June 2020.

- ^ a b Lewis 1848, pp. 124–128.

- ^ a b Greater Manchester Gazetteer, Greater Manchester County Record Office, Places names – B, archived from the original on 18 July 2011, retrieved 20 June 2007

- ^ a b c Great Britain Historical GIS Project (2004), "Bacup MB through time. Census tables with data for the Local Government District", A vision of Britain through time, University of Portsmouth, retrieved 27 October 2009

- ^ "National Lottery success for Stubbylee Hall". Heritage Trust Network. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ "Rossendale and Darwen", The Guardian, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ a b c Sellers 1991, pp. 265–268.

- ^ "Bacup, United Kingdom", Global Gazetteer, Version 2.1, Falling Rain Genomics, Inc, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001), Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 3 (PDF), Government of the United Kingdom, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007, retrieved 22 April 2008

- ^ Office for National Statistics (2001), Census 2001:Key Statistics for urban areas in the North; Map 9 (PDF), Government of the United Kingdom, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ Rossendale Borough Council, Towns and Villages, Government of the United Kingdom, archived from the original on 5 September 2009, retrieved 27 October 2009

- ^ Freethy, Ron (24 July 2007), "Tourist guide to Bacup", Lancashire Telegraph, lancashiretelegraph.co.uk, retrieved 27 October 2009 [dead link]

- ^ "The Bacup Natural History Society & Museum". Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "Street measures up to new record", BBC News, 1 November 2006, retrieved 9 August 2008

- ^ Housing and Planning Minister Reviews £2m Bacup Regeneration Scheme, OBAS Group, archived from the original on 2 April 2015, retrieved 3 March 2015

- ^ a b "Disused Stations: Bacup Station". disused-stations.org.uk.

- ^ Historic England, "Monument No. 1371976", Research records (formerly PastScape), retrieved 7 October 2015

- ^ a b "Police Monitoring Bacup Weir Accident Blackspot". The Bolton News. The Bolton News. 29 June 2014.

- ^ "UPDATED: Man fighting for life after Bacup crash". Bolton News. 26 April 2014.

- ^ a b The History of the Britannia Coconut Dancers, coconutters.co.uk, 2005, archived from the original on 5 March 2005, retrieved 11 November 2009

- ^ "index". bacupnaturalhistorysociety.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ "museum&archives". bacupnaturalhistorysociety.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Press, Rossendale Free (2 March 2007). "Film crews can't get enough of the Valley". rossendale. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Winter Hill (Bolton, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Freeview Light on the Bacup (Lancashire, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Rossendale Radio". Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ "Lancashire Telegraph". British Papers. 30 May 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2023.

- ^ Hibbs, James (27 September 2023). "Where is Brassic filmed?". Radio Times. Retrieved 8 November 2023.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 455; see last sentence.

- ^ Webb, Beatrice (1926, reprinted 1979), My Apprenticeship, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-29731-8

- ^ Grimshaw, Katie (3 September 2003), Betty Jackson – the Bacup girl done good, bbc.co.uk, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ Frankel, Susannah (9 June 2007), "Twenty-five years on, is Betty Jackson still a cut above?", independent, retrieved 28 October 2009[dead link]

- ^ "East Lancashire actors star in Coronation Street's special DVD", Lancashire Telegraph, lancashiretelegraph.co.uk, 7 November 2008, archived from the original on 25 March 2012, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ "Hereford United 2 Accrington Stanley 0", Accrington Observer, M.E.N. Media, 24 September 2009, archived from the original on 5 May 2013, retrieved 28 October 2009

- ^ "Pugh's Claret dream", Rossendale Free Press, M.E.N. Media, 2 October 2009, archived from the original on 5 May 2013, retrieved 28 October 2009

Bibliography

edit- Cameron, Kenneth (1961), English Place Names, Taylor & Francis

- Eagleton, Terry (1996), Heathcliff and the Great Hunger: Studies in Irish Culture, Verso, ISBN 978-1-85984-027-6

- Fenton, Mary C. (2006), Milton's places of hope: spiritual and political connections of hope with land, Ashgate, ISBN 978-0-7546-5768-2

- Hobsbawm, Eric (1996), The Age of Capital: 1848–1875, ISBN 978-0-679-77254-5

- Lewis, Samuel (1848), A Topographical Dictionary of England (extract), Institute of Historical Research, ISBN 978-0-8063-1508-9

- Miller, G. M. (1971), BBC Pronouncing Dictionary of British Names, Oxford University Press

- Mills, A. D. (2003), A Dictionary of British Place-Names, USA: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-852758-9

- Sellers, Gladys (1991), Walking the South Pennines, Cicerone Press, ISBN 978-1-85284-041-9

- Shuel, Brian (1985), National Trust Guide to Traditional Customs of Britain, Webb & Bower, ISBN 0-86350-051-X

- Farrer and Brownbill (1911), The Victoria History of the County of Lancaster Vol 6, Victoria County History – Constable & Co, OCLC 270761418

External links

edit- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 181.

- Historic Town Survey – Bacup, Lancs CC