The Awa'uq Massacre[4][5] or Refuge Rock Massacre,[5] or, more recently, as the Wounded Knee of Alaska,[2] was an attack and massacre of Koniag Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) people in August 1784 at Refuge Rock near Kodiak Island by Russian fur trader Grigory Shelekhov and 130 armed Russian men and cannoneers of his Shelikhov-Golikov Company.

| Awa'uq Massacre | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian colonization of the Americas and the American Indian Wars | |||

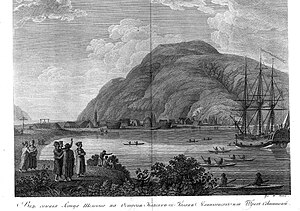

Grigory Shelikhov's settlement is depicted in this 1802 lithograph. Three Saints was founded in 1784 just across the strait from Sitkalidak Island. | |||

| Date | 14 August 1784 | ||

| Location | 57°06′22″N 153°05′00″W / 57.10604°N 153.0832814°W | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

none | |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

Massacre

editSince 1775 Shelekhov had been trading with Alaska Natives in the Kuril and Aleutian islands of present-day Alaska. In April 1784 he returned to found a settlement on Kodiak Island and the coast of the mainland. The people occupying the area initially resisted, and fled to the secluded stack island Refuge Rock (Awa'uq in Alutiiq language, approximate meaning 'where one becomes numb'[6]) of Partition Cove on Sitkalidak Island. It was across Old Harbor in the Kodiak Archipelago.[7]

The Russian promyshlennikis attacked the people on the island by shooting guns and cannons, slaughtering an estimated 200 to 500[8][2] men, women and children on Refuge Rock. Some sources state the number killed was as many as 2,000,[1] or 3,000 persons.[3] Following the attack of Awa'uq, Shelikhov claimed to have captured over 1,000 people, detaining some 400 as hostages, including children.[1] The Russians suffered no casualties.[3]

This massacre was an isolated incident, but the violence and taking of hostages resulted in the Alutiiq becoming completely subjugated by Russian traders thereafter.[9] Qaspeq (literally: "kuspuk"), was an Alutiiq (Sugpiaq) who had been taken as a child as a hostage from Kodiak; he was raised in servitude by the Russians in the Aleutians. Having learned Russian, he became an interpreter for them with the Alutiiq. Qaspeq had once betrayed the location of a refuge island just offshore of Unalaska Island.[10]

More than five decades after the massacre, Arsenti Aminak, an old Sugpiaq man who had survived the massacre, reported his account of these events to Henrik Johan Holmberg (sometimes known as Heinrich Johann) (1818–1864), a Finnish naturalist and ethnographer.[11] Holmberg was collecting data for the Russian governor of Alaska.[12]

Aminak said:

The Russians went to the settlement and carried out a terrible blood bath. Only a few [people] were able to flee to Angyahtalek in baidarkas; 300 Koniags were shot by the Russians. This happened in April. When our people revisited the place in the summer the stench of the corpses lying on the shore polluted the air so badly that none could stay there, and since then the island has been uninhabited. After this every chief had to surrender his children as hostages; I was saved only by my father's begging and many sea otter pelts. [13]

Aftermath

editThe years 1784–1818 were called the "darkest period of Sugpiaq history," as the Russians treated the people badly. They also suffered high mortality from infectious diseases unwittingly introduced by the Russians. In 1818 there was a change in the management of what was then known as the Russian-American Company, referring to Russians operating in North America.[14]

| year | Aleutian Islands (= Aleut ~ Unangan) |

Kodiak Island, Cook Inlet, Prince William Sound (= Alutiiq ~ Sugpiaq) |

Kodiak Island only (= Koniag Alutiiq) |

Cook Inlet, Prince William Sound only (= Chugach Sugpiaq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1741 | 8,000

|

|||

| 1784 | 10,000

|

|||

| 1791 | 6,000

|

6,510

|

599

| |

| 1804 | 4,850

|

|||

| 1806 | 1,898

|

|||

| 1813 | 1,508

|

|||

| 1817 | 4,098

|

2,544

| ||

| 1821 | 1.700

|

|||

| 1834 | 2,000

|

In 1827 collection of yasak (ясак) tax was banned by Catherine the Great.[12]

| 1797–1821 | Average/yr 1797–1821 |

1821–1842 | Average/yr 1821–1842 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sea otters | 72,894 | 2,916 | 25,416 | 1,210 |

| Beavers | 34,546 | 1,382 | 162,034 | 7,716 |

| River otters | 14,969 | 599 | 29,442 | 1,402 |

| Fur seals | 1,232,374 | 49,295 | 458,502 | 21,833 |

| Foxes | 102,134 | 4,085 | 90,322 | 4,301 |

| Sables | 17,298 | 692 | 15,666 | 746 |

| Wolverines | 1,151 | 46 | 1,564 | 74 |

| Lynx | 1,389 | 56 | 4,253 | 203 |

| Minks | 4,802 | 192 | 15,481 | 737 |

| Polar foxes | 40,596 | 1,624 | 69,352 | 3,302 |

| Wolves | 121 | 5 | 201 | 10 |

| Bears | 1,602 | 64 | 5,355 | 255 |

| Sea lions | 27 | 1 | Ø | 0 |

| Walrus tusks (poods = 36 pounds) | 1,616 | 65 | 6,501 | 310 |

| Baleen (poods = 36 pounds) | 1,173 | 47 | 3,455 | 165 |

References

edit- ^ a b c d Ben Fitzhugh (2003), The Evolution of Complex Hunter-Gatherers: archaeological evidence from the North Pacific, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2003

- ^ a b c John Enders (1992), "Archaeologist May Have Found Site Of Alaska Massacre", The Seattle Times, Sunday, August 16, 1992

- ^ a b c d The Afognak Alutiiq People: Our History and Culture, Alutiiq, a wholly owned subsidiary of Afognak Native Corporation, July 2008

- ^ Sven Haakanson, Jr. (2010), "Written Voices Become History". In Being and Becoming Indigenous Archaeologists. George Nicholas (editor). Left Coast press, Inc., 2010

- ^ a b Afognak Village Timeline

- ^ Finding Refuge, PBS, NETA, first release 3 Oct. 2015.

- ^ Gordon L. Pullar, "Ethnographie historique des villages sugpiat de Kodiak à la fin du XIXe siècle". In Giinaquq = Like a Face : Sugpiaq masks of the Kodiak archipelago (editors: Sven Haakanson Jr. and Amy Steffian), 2009 University of Alaska Press. {En 1784, peu après la prise de contrôle de l'île de Kodiak par les Russes qui avait entraîné le massacre de centaines de Sugpiat à Awa'uq (Refuge Rock), le marchand russe Grigorii Shelikhov prit en otage les enfants de reponsables sugpiaq pour les avoir sous son controle er, ainsi, contrôler tout leur peuple.}

- ^ Korry Keeker, What it means to be Alutiiq / State museum exhibit examines Kodiak-area Native culture Archived 2013-01-04 at the Wayback Machine, Friday, April 25, 2003

- ^ Aron L. Crowell (2001), Looking Both Ways, Heritage and Identity of the Alutiiq People. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2001

- ^ Richard A. Knecht, Sven Haakanson, and Shawn Dickson (2002). "Awa'uq: discovery and excavation of an 18th century Alutiiq refuge rock in the Kodiak Archipelago". In To the Aleutians and Beyond:, Bruno Frohlich, Albert S. Harper, and Rolf Gilberg, editors, pp. 177–191. Publications of the National Museum Ethnographical Series, Vol. 20. Department of Ethnography, National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen. the Anthropology of William S. Laughlin.

- ^ Drabek, Alisha Susana 2012. Liitukut Sugpiat'stun (we are learning how to be real people): Exploring Kodiak Alutiiq literature through core values. PhD dissertation. University of Alaska at Fairbanks, Fairbanks, Alaska, December 2012.

- ^ a b Miller, Gwenn A. (2010). Kodiak Kreol: Communities of Empire in Early Russian America. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4642-9.

- ^ Heinrich J. Holmberg (1985), Holmberg's Ethnographic Sketches. Translated by Marvin W. Falk, edited by Fritz, Fairbanks: Limestone Press, 1985 (p. 59)

- ^ Lydia T. Black (1992), "The Russian Conquest of Kodiak." In: Anthropological Papers of the University of Alaska. Vol. 24, Numbers 1-2. Fall. Department of Anthropology, University of Alaska Fairbanks

- ^ a b "Russian American Reader" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-02. Retrieved 2014-10-21.