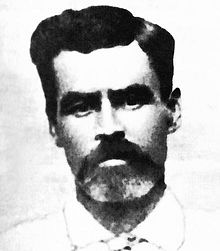

Augustine Chacon (1861 – November 21, 1902), nicknamed El Peludo (English: "The Hairy One"), was a Mexican outlaw and folk hero active in the Arizona Territory and along the U.S.–Mexico border at the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century. Although a self-proclaimed badman, he was well-liked by many settlers, who treated him as a Robin Hood-like character rather than a typical criminal. According to Old West historian Marshall Trimble, Chacon was "one of the last of the hard-riding desperados who rode the hoot-owl trail in Arizona around the turn of the century." He was considered extremely dangerous, having killed about thirty people before being captured by Burton C. Mossman and hanged in 1902.[1]

Augustine Chacon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1861 Sonora, Mexico |

| Died | November 21, 1902 (aged 40–41) Solomonville, Arizona Territory, United States |

| Cause of death | Execution by hanging |

| Nationality | Mexican |

| Other names | El Peludo |

| Known for | Armed robbery, cattle rustling, horse theft |

Biography

editEarly life

editChacon was born in 1861 in the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora, which was a sparsely populated wilderness at the time. He is first recorded in history as being a peace officer in the town of Sierra del Tigre, though he also found work hauling wood and ore at some point. In 1888 or 1889, Chacon moved across the international border to Morenci, Arizona, where he became known as an "excellent cowboy throughout the Arizona Territory." However, in 1890, he had a disagreement with his employer, a rancher named Ben Ollney, about three months' worth of pay. For some reason, Ben refused to pay Chacon his wages so the two "exchanged heated words" before the latter rode off towards Safford in disgust.

After spending the night drinking, Chacon armed himself and then returned to the ranch on the next day with the intention of collecting his money. Once again, Ollney refused to pay, but he went even further by insulting Chacon and laughing at him. Ollney attempted to draw his pistol, but Chacon drew first and shot his antagonist dead. Five cowboys rushed to the scene to avenge their slain employer, but Chacon held his ground and shot all of them. Four of them died, but the fifth escaped to Whitlock Springs, where he raised the alarm. Ben Ollney's brother lived at Whitlock Springs and quickly organized a posse of six men to go after Chacon, who by that time was fleeing south towards the border. The posse followed Chacon's trail to a box canyon, cornered him in and then called out for his surrender, but Chacon equipped himself with two revolvers and charged his pursuers on horseback. Four more cowboys were killed and Chacon rode off with a slight arm wound.[2][3]

According to author R. Michael Wilson, the entire Ollney family[clarification needed] was killed in Whitlock Springs two days later, but Chacon claimed he was at a Mexican woodcutter's camp when the murders occurred, tending to his wound and accompanied by a pair of Arizona train robbers, Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles. Several months passed before Chacon was found to be back in Arizona. He was arrested near Fort Apache while visiting a girl and the next day a lynch mob formed to carry out an illegal hanging. However, when the mob made it to the jail all they found was an empty cell, Chacon having cut the window's metal bars with a hacksaw and slipped out. Some locals claimed that Ben Ollney's daughter, Nelly, delivered Chacon the saw because she did not believe he had killed her father.[2][3]

Chacon Gang

editOver the next few years, Chacon led a gang which operated primarily as horse thieves and cattle rustlers. They lived in the Sierra Madre of Sonora, but routinely crossed into Arizona to commit crimes and sell off stolen property. The author of Famous sheriffs & western outlaws, William MacLeod Raine, says that Chacon's band was the "worst gang of outlaws that ever infested the border." Multiple murders, rapes, robberies and other crimes were attributed to the gang, but they always seemed to escape capture.

Many notable lawmen became involved in the pursuit of Chacon and his bandits, among them John Horton Slaughter, a sheriff and veteran gunfighter. Once, at Tombstone, Chacon was caught bragging that he would kill Slaughter on sight so the sheriff investigated and was told by an informant where Chacon was held up. Later that night, Slaughter and his then-deputy Burt Alvord surrounded the canvas tent Chacon was sleeping in, but when they called on him to surrender, the bandit jumped up and started running out the back entrance. Slaughter fired once with his shotgun and assumed he hit Chacon, since he had tumbled into a nearby ditch. But when the lawmen got down to the bottom, they found no body and decided Chacon must have tripped on a rope at the foot of the tent and the shotgun blast passed over his head.

In late 1894, two employees of the Detroit Copper Company were hunting along Eagle Creek in Arizona when they were murdered by a band of outlaws. The Chacon gang often slaughtered stolen cattle in the area, and the people of Morenci decided the bandits were responsible. Not long after that, the body of an old miner was found concealed in an abandoned mine shaft and again Chacon was blamed.[4][5][6][7]

Chacon and his men also robbed a casino in Jerome, killing four people in the process, and later held up a stagecoach outside Phoenix. Furthermore, a group of sheep-shearers were found dead at their camp around this time and, as usual, Chacon was said to have been responsible.[1][8]

Gunfight at Morenci

editThe most famous gunfight involving the Chacon gang occurred in 1895, after they robbed a general store in Morenci. On the night of December 18, Chacon and two of his followers, Pilar Franco and Leonardo Morales, entered McCormack's store, which was managed by a man named Paul Becker. After stabbing the manager in his sleeping quarters, the bandits looted the place and then headed for their cabin, which was located on top of a steep hill that overlooked the town. Becker, who was still alive, waited until the robbers were gone and then went to a nearby saloon to notify the police. On the following morning, Constable Davis, who also served as the sheriff of Graham County, organized a posse and began following the bandits' trail, which clearly led to the cabin. There Chacon was waiting for the posse with Franco and Morales; author R. Michael Wilson says that there were also two other men with them, making a total of five bandits altogether. As Davis and his deputies approached the cabin, suddenly Chacon and his men burst out the front door, running for a pile of boulders and firing their guns wildly. The fighting continued for several moments but eventually the possemen stopped shooting long enough to demand a surrender. One of the deputies was a man named Pablo Salcido, who volunteered to approach the gang's position and speak with them. After calling out to Chacon, Salcido was invited to move forward, but, when he exposed himself, Chacon fired a single shot with his rifle and struck the deputy in the head, killing him instantly. The fighting immediately resumed and it lasted until over 300 rounds of ammunition had been expended. Near the end of the skirmish, Franco and Morales chose to make a run for it, leaving Chacon to fend for himself. A few of the possemen went after the fleeing bandits, killing them both, and when the return fire ceased they were able to move in and capture Chacon, who was temporarily paralyzed by bullet wounds to his chest and shoulder.[9][10]

The gunfight at Morenci was the bloodiest shootout in the town's history and when it was over Chacon was taken to jail and his gang members were either killed or in hiding. Chacon was initially held in the Clifton Jail, but was later sent to Solomonville to face the court for the murder of Pablo Salcido. Judge Owen T. Rouse sentenced Chacon to hang on July 24, 1896, but his case was appealed on May 26 after he pleaded innocent. Chacon claimed he would never have killed Salcido, who he claimed was a friend he had worked with years before as a cowboy. For this, Chacon was moved to Tucson to await the Supreme Court's decision, but they affirmed the lower court's ruling and he was sent back to Solomonville to be hanged on June 18, 1897.

However, on June 9, Chacon escaped from his jail cell once again.[11] R. Michael Wilson says that the "jail's walls were ten inches of adobe with a double layer of two inch pine boards held together with five inch nails." Wilson says that if Chacon dug his way through the walls it would have created a lot of noise so the guards were suspected of "turning a deaf ear." Author Jan Cleere contradicts this, claiming that some fellow prisoners played guitars and sang to cover up the sounds. Marshall Trimble agrees with Cleere, but also says that a young Mexican woman distracted the jailer by seducing him. Either way, Chacon was free again and he fled back across the border into Sonora. Nobody ever discovered how Chacon was supplied with tools for his escapes, though, according to Cleere, visiting friends probably gave them to him one at a time. According to William MacLeod Raine, Chacon went to Mexico and enlisted in the Rurales, but, after a year and a half, he had a dispute with another soldier and returned to banditry.[9][12][13]

Burton C. Mossman

editAt the turn of the century, Arizona was still the wild place it had been for years previously, especially near the border with Mexico. Armed robbery and rustling was so widespread that in March 1901 the territorial governor, Oakes Murphy, authorized the re-establishment of the Arizona Rangers. Burton C. Mossman was the first captain of the unit and his final accomplishment before resigning was tricking Augustine Chacon into crossing the border, where he could be apprehended legally. To do this, Mossman came up with an idea that involved posing as an outlaw and recruiting the train robber Burt Alvord, who was a friend of Chacon, to use him as a stool pigeon. However, to recruit Alvord, Mossman had to find his hideout in Sonora, where he would be totally helpless against both the bandits and Mexican authorities. Mossman had previously attempted and failed to capture Alvord and his gang. This time, Mossman hoped that Alvord would be willing to help him with Chacon and then surrender in exchange for a lighter sentence as well as the reward money offered for Chacon's head.

On April 22, 1902, after traveling for several days by wagon and on horseback, Mossman discovered Alvord's hideout, a small hut located some distance away from San Jose de Pima. The captain approached the hut unarmed and by chance found Alvord standing alone outside while the rest of the gang played cards inside. Mossman was first to introduce himself and though Alvord was immediately alarmed about the presence of a police officer at his hideout, he offered to feed Mossman and listen to what he had to say. When it was obvious that Mossman was not trying to fool Alvord, the two men agreed to cooperate. Another outlaw Billy Stiles acting as their messenger, for it would take a while for Alvord to find Chacon and convince him to cross the Arizona border and somebody had to warn the captain when the bandits arrived. When he finally did catch up with Chacon, over three months later, Alvord first accompanied him to the Yaqui River to sell stolen horses before going all the way back to the border. As the bandits were nearing the rendezvous, Alvord sent Stiles ahead to tell Mossman to meet them just south of the border, at the Socorro Mountain Springs in Sonora.[14][15]

Mossman and Stiles failed to meet Alvord and Chacon in the Socorro Mountains, but, on the following night, they found the bandits at the home of Alvord's wife. There, after exchanging names, Mossman and the others agreed to cross the border back into Arizona the next day so they could steal some horses from Greene's Ranch that night. However, when it came time, it was decided that it was too dark for stealing horses so the party went back to their camp, which was located less than seven miles from the border. According to Raine, just before daybreak on September 4, 1902, Alvord was preparing to leave when he "tiptoed" over to Mossman and said: "I brought Chacon to you, but you don't seem able to take him. I've done my share and I don't want him to suspect me. Remember that if you take him you have promised that the reward shall go to me, and that you'll stand by me at my trial if I surrender. You sure want to be mighty careful, or he'll kill you. So long."

When Chacon awoke later that morning his suspicions were aroused when he found that Alvord was no longer in camp. After breakfast, Stiles suggested they steal the horses in daylight, but Chacon was uninterested and said he was going back to Sonora. Mossman knew his time to act was now. Chacon and Stiles were sitting on the ground next to each other when Mossman stood up. First he asked for and received a cigarette from Chacon, then, as he dropped the twig he used to light his cigarette, Mossman pulled out his revolver and aimed it at Chacon. According to Raine, Mossman said, "Hands up, Chacon," to which the bandit said, "Is this a joke?" Mossman replied: "No. Throw your hands up or you're a dead man." Chacon then said: "I don't see as it makes any difference after he is dead whether man's hands are up or down. You're going to kill me anyway, why don't you shoot?" Mossman had Stiles disarm Chacon and then put him on a horse for the journey to the railroad, where they boarded a train to Benson, Arizona. Chacon attempted to escape several times along the way by throwing himself off his horse, presumably at a place where Mossman could not easily follow, such as a steep hillside.[14][16]

Death

editThe final capture of Chacon proved to be anticlimactic, but Mossman's plan worked exactly as he had hoped. At Benson, Mossman delivered Chacon to Jim Parks, the new sheriff of Graham County, and from there he was returned to Solomonville. Because he had already been sentenced to hang, Chacon's appearance in the Solomonville courthouse was merely to set a new date for execution. The first day chosen was November 14, 1902, but a group of local citizens petitioned to have Chacon's sentence reduced to life in prison. The effort failed, and the court decided to hang Chacon on November 21.

While waiting, Chacon was held in a specially built steel cage that was kept under heavy guard. The scaffold on which Chacon was to hang had also been built specifically for him in 1897, though he had escaped before it could be used. A large fourteen-foot adobe wall was built around the scaffold so only people with invitations could view the hanging. When the day of execution came, Chacon had a good breakfast and was permitted to see two of his friends, Jesus Bustos and Sisto Molino. He was also allowed to see the Catholic priest several times that day and after lunch he was given a shave and a new black suit to wear. Chacon was delivered to the scaffold at 2:00 PM and, as he entered the courtyard, about fifty people were waiting to greet him. The bandit chief, who had for over a decade eluded the law, asked for a cigarette and a cup of coffee before death and then began an unprepared thirty-minute speech to the crowd. Speaking in Spanish with an English interpreter, Chacon claimed he was innocent of killing his friend, Pablo Salcido, or anybody else for that matter, but he did say that he was guilty of stealing and "many other things." After a second cigarette and cup of coffee, Chacon requested that he be allowed to live until 3:00 pm, but his request was denied. While walking up the steps of the scaffold, Chacon shook the hands of his friends and admirers. When the rope was in place and the executioner was ready, Chacon's final words were "Adios, todos amigos." On the day after the execution, the Arizona Bulletin reported: "[A] nervier man than Augustine Chacon never walked to the gallows, and his hanging was a melodramatic spectacle that will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it."[16][17]

Augustine Chacon was known to have fathered at least one child in his lifetime, a son, and his descendants still live today. In 1980, some of Chacon's family members dedicated a marble gravestone at the San Jose Cemetery, which holds his remains.[18] Chacon's gravestone says the following:

- AUGUSTINE CHACON

- 1861–1902

- HE LIVED LIFE WITHOUT FEAR,

- HE FACED DEATH WITHOUT FEAR.

- HOMBRE MUY BRAVO[18]

In popular culture

editThe native Mexican-born actor Rodolfo Hoyos, Jr., played Chacon in a 1955 episode of the syndicated television series Stories of the Century, starring and narrated by Jim Davis.[19]

References

edit- ^ a b "The Escape of Desperado Augustine Chacon |". Arizonaoddities.com. 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ a b Wilson, pp. 43–44

- ^ a b Cleere, p. 66

- ^ Raine, p. 244

- ^ McClintock, p. 470

- ^ Cleere, p. 67

- ^ "Gunslinger Saints – John Slaughter". Jcs-group.com. Archived from the original on 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- ^ Trimble, p. 350

- ^ a b Wilson, p. 44

- ^ Cleere, pp. 67–68

- ^ Proclamation of Reward, July 31, 1897, The Florence Tribune

- ^ Cleere, pp. 68–69

- ^ Raine, p. 69

- ^ a b Raine, pp. 74–77

- ^ Cleere, p. 69

- ^ a b Wilson, p. 45

- ^ Cleere, pp. 71–73

- ^ a b Cleere, pp. 72–73

- ^ "Stories of the Century: Augustine Chacon", January 30, 1955". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 5, 2012.

- Trimble, Marshall (1986). Roadside history of Arizona. Mountain Press Pub. Co. ISBN 978-0878421978.

- Wilson, R. Michael (2005). Legal Executions in the Western Territories, 1847–1911: Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Dakota, Utah, Washington and Wyoming. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786448258.

- Cleere, Jan (2006). Outlaw Tales of Arizona: True Stories of Arizona's Most Nefarious Crooks, Culprits, and Cutthroats. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0762728145.

- Raine, William MacLeod (1944). Famous sheriffs & western outlaws. The New home library.

- Raine, William MacLeod (1905). Pearson's Magazine: Carrying Law into the Mesquite. Pearson Publishing Co.

- McClintock, James H. (1916). Arizona, prehistoric, aboriginal, pioneer, modern: the nation's youngest commonwealth within a land of ancient culture, Volume 2. The S.J. Clarke publishing co.