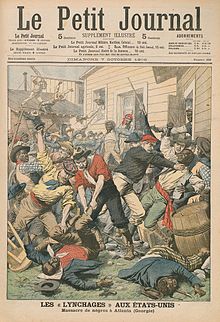

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. [1] The violence lasted through September 24, 1906.[2] The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta,"[3] the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia,"[4] and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia."[5] The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans[6] and two whites died.[7] Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre.[8] According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

| 1906 Atlanta race massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Nadir of American race relations | |

The cover of French magazine Le Petit Journal in October, 1906, depicting the Atlanta race riot | |

| Location | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Date | September 22–24, 1906 |

| Target | African Americans |

| Deaths | 25+ African Americans, 2 white Americans |

| Injured | 90+ African Americans, 10 white Americans |

| Perpetrators | White mobs, and Fulton county police. |

The immediate catalyst was newspaper reports of four white women raped in separate incidents, allegedly by African American men. A grand jury later indicted two African Americans for raping Ethel Lawrence and her niece Mabel Lawrence. An underlying cause was the growing racial tension in a rapidly changing city and economy, competition for jobs, housing, and political power.

The violence did not end until after Governor Joseph M. Terrell called in the Georgia National Guard, and African Americans accused the Atlanta Police Department and some Guardsmen of participating in the violence against them. Local histories by whites ignored the massacre for decades. It was not until 2006 that the event was publicly marked – on its 100th anniversary. The next year, the Atlanta massacre was made part of the state's curriculum for public schools.[9]

Background

editGrowth of Atlanta

editAfter the end of the American Civil War and during the Reconstruction era, there was violence of whites against blacks throughout the South, as whites reacted to emancipation of blacks, accusations of black criminality, and political empowerment of freedmen, specifically gaining the voting franchise which led to political power and representation. Having former slaves become equals was threatening to their ideals of racial supremacy. Increased tension also resulted from whites competing with blacks for wages, and the idea of paying for labor which had been free for centuries. Atlanta had developed rapidly, attracting workers for its rebuilding and, particularly from the 1880s as the "rail hub" of the South: workers from all over the country began to flood the city. This resulted in a dramatic increase in both the African-American population (9,000 in 1880 to 35,000 in 1900) and the overall city population (from a population of 89,000 in 1900 to 150,000 in 1910)[10] as individuals from rural areas and small towns sought better economic opportunities.[11]

With this influx and the subsequent increase in the demand for resources, race relations in Atlanta became increasingly strained in the crowded city.[11] Whites expanded Jim Crow segregation in residential neighborhoods and on public transportation.[10]

African-American advancements

editFreedmen and their descendants had gained the franchise during Reconstruction, and whites increasingly feared and resented their exercise of political power. African Americans had established prosperous businesses and developed an elite who distinguished themselves from working-class blacks. Some whites resented them. Among the successful black businessmen was Alonzo Herndon, who owned and operated a large, refined barber shop that served prominent white men. This new status brought increased competition between blacks and whites for jobs and heightened class distinctions.[12][13] The police and fire department were still exclusively white, as were most employees in the city and county governments.

State requirements from 1877 limited black voting through poll taxes, record keeping and other devices to impede voter registration, but many freedmen and descendants could still vote. But both major candidates played on racial tensions during their campaigning for the gubernatorial election of 1906, in which M. Hoke Smith and Clark Howell competed for the Democratic primary nomination. Smith had explicitly "campaigned on a platform to disenfranchise black voters in Georgia."[14] Howell was also looking to exclude them from politics. Smith was a former publisher of the Atlanta Journal and Howell was the editor of the Atlanta Constitution. Both candidates used their influence to incite white voters and help spread the fear that whites may not maintain the current social order.[12] These papers and others attacked saloons and bars that were run and frequented by black citizens. These "dives", as whites called them, were said to have nude pictures of women. The Atlanta Georgian and the Atlanta News publicized police reports of white women who were allegedly sexually molested and raped by black men.[12]

Events

editThe Clansman and tensions

edit"Historians and contemporary commentators cite the stage production of The Clansman [by Thomas Dixon, Jr.] in Atlanta as a contributing factor to that city's race riot of 1906, in which white mobs rampaged through African-American communities."[15] In Savannah, where it opened next, police and military were on high alert, and present on every streetcar going toward the theater.[16] Authorities in Macon, where the play was next to open, asked for it not to be permitted, and it was not.[17]

Newspaper report and attacks

editOn Saturday afternoon, September 22, 1906, Atlanta newspapers reported four sexual assaults on local white women, allegedly by black men, including brutal attacks on Ethel Lawrence and her niece, Mabel Lawerence.[18] Mabel, an Englishwoman visiting her brother in Atlanta, and her niece were picking ferns or wildflowers when they were attacked. She was hospitalized with severe injuries and lost an eye.[19] Following this report, several dozen white men and boys began gathering in gangs, and began to beat, stab, and shoot black people in retaliation, pulling them off or assaulting them on streetcars, beginning in the Five Points section of downtown. After extra editions of the paper were printed, by midnight estimates were that 10,000 to 15,000 white men and boys had gathered through downtown streets and were roaming to attack black people.[20] By 10 pm, the first three blacks had been killed and more were being treated in the hospital (at least five of whom would die); among these were three women. Governor Joseph M. Terrell called out eight companies of the Fifth Infantry and one battery of light artillery.[20] By 2:30 am, some 25 to 30 blacks were reported dead, with many more injured. The trolley lines had been closed before midnight to reduce movement, in hopes of discouraging the mobs and offering some protection to the African-American neighborhoods, as whites were going there and attacking people in their houses, or driving them outside.[20]

Alonzo Herndon's barbershop was among the first targets of the white mob, and the fine fittings were destroyed.[21] Individual black men were killed on the steps of the US Post Office and inside the Marion Hotel, where a crowd chased one. During that night, a large mob attacked Decatur Street, the center of black restaurants and saloons. It destroyed the businesses and assaulted any black people within sight. Mobs moved to Peters Street and related neighborhoods to wreak more damage.[20] Heavy rain from 3 am to 5 am helped suppress the fever for rioting.[22]

The events were quickly publicized the next day, Sunday, as violence continued against black people, and the massacre was covered internationally. Le Petit journal of Paris reported, "Black men and women were thrown from trolley-cars, assaulted with clubs and pelted with stones."[3] By the next day, the New York Times reported that at least 25 to 30 black men and women were killed, with 90 injured. One white man was reported killed, and about 10 injured.[22]

An unknown and disputed number of black people were killed on the street and in their shops, and many were injured. In the center of the city, the militia was seen by 1 am. But most were not armed and organized until 6 am when more were posted in the business district. Sporadic violence had continued in the late night in distant quarters of the city as small gangs operated. On Sunday hundreds of black people left the city by train and other means, seeking safety at a distance.[22]

Defense attempts

editOn Sunday a group of African Americans met in the Brownsville community south of downtown and near Clark University to discuss actions; they had armed themselves for defense. Fulton County police learned of the meeting and raided it; an officer was killed in an ensuing shootout. Three militia companies were sent to Brownsville, where they arrested and disarmed about 250 blacks, including university professors.[23][24]

The New York Times reported that when Mayor James G. Woodward, a Democrat, was asked as to the measures taken to prevent a race riot, he replied:

The best way to prevent a race riot depends entirely upon the cause. If your inquiry has anything to do with the present situation in Atlanta then I would say the only remedy is to remove the cause. As long as the black brutes assault our white women, just so long will they be unceremoniously dealt with.[25]

Aftermath

editGrand Jury

editOn September 28, The New York Times reported,

The Fulton County Grand Jury today made the following presentment:

"Believing that the sensational manner in which the afternoon newspapers of Atlanta have presented to the people the news of the various criminal acts recently committed in this county has largely influenced the creation of the spirit animating the mob of last Saturday night; and that the editorial utterances of The Atlanta News for some time past have been calculated to create a disregard for the proper administration of the law and to promote the organization of citizens to act outside of the law in the punishment of crime;

...Resolved, That the sensationalism of the afternoon papers in the presentation of the criminal news to the public prior to the riots of Saturday night... deserves our severest condemnation..."[26]

Total fatalities

editAn unknown and disputed number of black people were killed in the conflict. At least two dozen African Americans were believed to have been killed. It was confirmed that there were two white deaths, one a woman who died of a heart attack after seeing mobs outside her house.[citation needed]

Discussions

editOn the following Monday and Tuesday, leading citizens of the white community, including the mayor, met to discuss the events and prevent any additional violence. The group included leaders of the black elite, helping establish a tradition of communication between these groups. But for decades the massacre was ignored or suppressed in the white community, and left out of official histories of the city.[citation needed]

Responses

editThe New York Times noted on September 30 that a letter writer to the Charleston News and Courier wrote in response to the riots:

Separation of the races is the only radical solution of the negro problem in this country. There is nothing new about it. It was the Almighty who established the bounds of the habitation of the races. The negroes were brought here by compulsion; they should be induced to leave here by persuasion.[27]

The New York Times analyzed the populations of the ten states in the South with the most African Americans, two of which were majority black, with two others nearly equal in populations, and African Americans totaling about 70% of the total white population. It noted practically the difficulties if so many workers would be lost, in addition to their businesses.[27]

As an outcome of the massacre, the African-American economy suffered, because of property losses, damage, and disruption. Some individual businesses were forced to close. The community made significant social changes,[28] pulling businesses from mixed areas, settling in majority-black neighborhoods (some of which was enforced by discriminatory housing practices into the 1960s), and changing other social patterns. In the years after the massacre, African Americans were most likely to live in predominately black communities, including those that developed west of the city near Atlanta University or in eastern downtown. Many black businesses dispersed from the center to the east, where the thriving black business district known as "Sweet Auburn" soon developed.[29]

Many African Americans rejected the accommodationist position of Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute, believing that they had to be more forceful about protecting their communities and advancing their race. Some black Americans modified their opinions on the necessity of armed self-defense, even as many issued explicit warnings about the dangers of armed political struggle. Harvard-educated W. E. B. Du Bois, who was teaching at Atlanta University and supported leadership by the "Talented Tenth", purchased a shotgun after rioting broke out in the city. He said in response to the carnage, "I bought a Winchester double-barreled shotgun and two dozen rounds of shells filled with buckshot. If a white mob had stepped on the campus where I lived I would without hesitation have sprayed their guts over the grass."[28] As his position solidified in later years, circa 1906–1920, Du Bois argued that organized political violence by black Americans was folly. Still, in response to real-world threats on black people, Du Bois "was adamant about the legitimacy and perhaps the duty of self-defense, even where there [might be a] danger of spillover into political violence."[28]

Elected in 1906, Governor Hoke Smith fulfilled a campaign promise by proposing legislation in August 1907 for a literacy test for voting, which would disenfranchise most blacks and many poor whites through subjective administration by whites. In addition, the legislature included provisions for grandfather clauses to ensure whites were not excluded because of lack of literacy or the required amount of property, and for the Democratic Party to have a white primary, another means of exclusion. These provisions were passed by constitutional amendment in 1908, effectively disfranchising most blacks.[14] Racial segregation was already established by law. Both systems under Jim Crow largely continued into the late 1960s.

After World War I, Atlanta worked to promote racial reconciliation and understanding by creating the Commission on Interracial Cooperation in 1919; it later evolved into the Southern Regional Council.[30] But most institutions of the city remained closed to African Americans. For instance, no African-American policemen were hired until 1948, after World War II.

Remembrance

editThe massacre was not covered in local histories and was ignored for decades. In 2006, on its 100th anniversary, the city and citizen groups marked the event with discussions, forums and related events such as "walking tours, public art, memorial services, numerous articles and three new books."[9] The next year, it was made part of the state's social studies curriculum for public schools.[9]

Representation in other media

edit- WABE published the audio walk 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre Walking Tour recorded with the late historian and Georgia State University professor Clifford Kuhn.

- The film documentary When Blacks Succeed: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot (2006) by Norman and Clarissa Myrick Harris was produced by One World Archives and won awards.

- Thornwell Jacobs wrote a novel, The Law of the White Circle, set during the 1906 massacre. It has a foreword written by historian W. Fitzhugh Brundage, and has supplemental materials by Paul Stephen Hudson and Walter White, long-term president of the NAACP.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Kuhn, C. & Mixon, G., "Atlanta Race Massacre of 1906" Georgia Humanities (2022) [1]

- ^ Charles Crowe, "Racial Massacre in Atlanta: September 22, 1906." Journal of Negro History 54.2 (1969): 150–173. online

- ^ a b "Un lynchage monstre" (September 24, 1906) Le Petit Journal

- ^ "The Race Riots in Georgia". Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Aberdeen Press and Journal. September 25, 1906. p. 6.

- ^ "Anti-Negro Riots". London, England. London Evening Standard. September 26, 1906. p. 7.

- ^ Burns, Rebecca (September 2006). "Four Days of Rage". Atlanta Magazine: 141–145.

- ^ "Whites and Negroes Killed at Atlanta; Mobs of Blacks Retaliate for Riots – Two Whites Killed; Many Negroes Surrounded; Two of Band That Killed an Officer Try to Escape, but Are Captured and Lynched." (September 25, 1906) New York Times

- ^ "The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre: How Fearmongering Led to Violence". November 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c Shaila Dewan, "100 Years Later, a Painful Episode Is Observed at Last", New York Times, 24 September 2006; accessed 30 March 2018

- ^ a b Mixon, Gregory, and Clifford Kuhn. "Atlanta Race Riot of 1906", New Georgia Encyclopedia, 29 October 2015; accessed 26 March 2018

- ^ a b Steinberg, Arthur K. "Atlanta Race Riot (1906)." Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia[permanent dead link], edited by Steven L. Danver, vol. 2, ABC-CLIO, 2011, pp. 681–684

- ^ a b c Burns 2006:4–5

- ^ Walter C. Rucker, James N. Upton 2007. Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Greenwood Publishing Group pp. 14–20

- ^ a b "August 21, 1907: Literacy Test Proposed", This Day in Georgia History, Georgia Info, University Libraries

- ^ Leiter, Andrew. "Thomas Dixon, Jr.: Conflicts in History and Literature". Documenting the American South. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ "Rioting Feared by Savannah". Atlanta Constitution. September 25, 1906. p. 3.

- ^ "The Clansman Barred by Macon". Atlanta Constitution. September 25, 1906. p. 3.

- ^ Millin, Eric Tabor (2002). "Defending the Sacred Hearth: Religion, Politics, and Racial Violence in Georgia, 1904-1906" (PDF). University of Georgia LIbrary. p. 90. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

On August 20th, the newspapers reported that a black man had brutally beaten Ethel Lawrence, age 30, and her niece Mabel Lawrence, age 14.

- ^ Godshalk, David Fort (2006). Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American Race Relations. University of North Carolina Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8078-5626-0. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Atlanta Mobs Kills Ten More Negroes; Maybe 25 or 30 – Assaults on Women the Cause; Slain Wherever Found; Cars Stopped in Streets, Victims Torn from Them; Militamen Called Out; Trolley Systems Stopped to Keep the Mob from Reaching the Negro Quarter", New York Times, 23 September 1906

- ^ When Blacks Succeed: The Atlanta Race Riot of 1906 (2006), part 1

- ^ a b c "Rioting Goes On Despite Troops; Negro Lynched, Another Shot, in Atlanta; Saturday's Dead Eleven; Exodus of Black Servants Troubles City; Mayor Blames Negroes; Leading Citizens Condemn the Rioters and Demand Cessation of Race Agitation – Many Injured", New York Times (September 24, 1906)

- ^ "3,000 Georgia Troops Keep Peace in Atlanta; Soldiers Disarming Negroes in All Parts of the City; Hundreds Caught in Raid; Clark University Professors Among Prisoners – Whites and Negroes Meet to Demand Peace", (September 26, 1906 ) New York Times

- ^ "Georgia National Guard correspondence regarding the Atlanta Race Riot". Incoming Correspondence, Adjutant General, Defense, RG 22-1-17, Georgia Archives. Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved June 19, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The Atlanta Riots" (September 25, 1906) New York Times

- ^ "Paper Blamed for Riots; Grand Jury Accuses Atlanta News of Stirring Up Race Feeling" (September 28, 1906) New York Times

- ^ a b "Deporting the Negroes" (September 30, 1906) New York Times

- ^ a b c Johnson, Nicholas (2014). Negroes and The Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms. Amherst, New York: Prometheus. pp. 151–157. ISBN 978-1-61614-839-3.

- ^ Myrick-Harris, Clarissa (2006). "The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta, 1880–1910". Perspectives. 44 (8): 28. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Newman, Harvey K.; Crunk, Glenda (2008). "Religious Leaders in the Aftermath of Atlanta's 1906 Race Riot". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 92 (4): 460–485. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

Sources

edit- Allen, Josephine (2005). "Atlanta, Georgia". Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History (2nd ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster and the Trustees of Columbia University in the City of New York. ISBN 978-0-02-865816-2.

- Baker, Ray Stannard (1908). Following the Color Line: An Account of Negro Citizenship in the American Democracy. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Bauerlein, Mark (2001). Negrophobia: A Race Riot in Atlanta, 1906. San Francisco: Encounter Books. ISBN 1-893554-54-6.

- Burns, Rebecca (2006). Rage in the Gate City: The Story of the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot. Emmis Books. ISBN 1-57860-268-8.

- Case, Sarah. “1906 Race Riot Tour,” Journal of American History 101, no. 3 (December 2014): 880–882.

- Crowe, Charles. “Racial Massacre in Atlanta, September 22, 1906,” Journal of Negro History 54, no. 2 (April 1969): 150–173.

- Crowe, Charles. "Racial Violence and Social Reform-Origins of the Atlanta Riot of 1906." Journal of Negro History 53.3 (1968): 234–256. online

- Curtis, Wayne (June 29, 2018). "The Bar at the Center of Atlanta's Deadly 1906 Race Riot". Daily Beast.

- Godshalk, David Fort (2006). Veiled Visions: The 1906 Atlanta Race Riot and the Reshaping of American Race Relations. The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5626-6.

- Mixon, Gregory (2005). The Atlanta Riot: Race, Class, And Violence In A New South City. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2787-X.

External links

edit- "Defending Home and Hearth: Walter White Recalls the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot", History Matters

- NPR: Atlanta Race Riot

- Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, The New Georgia Encyclopedia

- An appeal to reason: an open letter to John Temple Graves, by Kelly Miller. c1906. (searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- The Atlanta riot: a discourse [delivered] October 7, 1906, by Francis J. Grimke. 1906. (searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu & layered PDF format)

- Brief summary of Events

- "Events at Atlanta", Brief overview with interview, PBS

- Brief overview of 1906 Race Riot

- Georgia National Guard orders and reports regarding the Atlanta Race Riot, 1906. From the collection of the Georgia Archives.

- Georgia National Guard correspondence regarding the Atlanta Race Riot, 1906. From the collection of the Georgia Archives.

- The Coalition To Remember 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre