Astyanax altior, the Yucatán tetra,[2][3] is a small species of freshwater fish endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. It largely inhabits the cenotes (water-filled sinkholes) of the region, and can tolerate water of limited salinity, though it largely prefers freshwater. Its diet includes plant matter and invertebrates, and there may be an element of cannibalism involved.

| Astyanax altior | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Characiformes |

| Family: | Characidae |

| Genus: | Astyanax |

| Species: | A. altior

|

| Binomial name | |

| Astyanax altior Hubbs, 1936

| |

It bears a genetic and morphological resemblance to congener Astyanax aeneus, with which it was once considered synonymous; however, more recent ecobiological assessment has determined that the two are separate.

Taxonomy

editAstyanax altior was first described in 1936 by Carl Leavitt Hubbs, an American ichthyologist.[4] He gave it the basionym Astyanax fasciatus altior, designating it a subspecies of Astyanax fasciatus.[5] Before that, populations of A. altior were considered populations of Astyanax aeneus (which used to be known as Astyanax fasciatus aeneus).[6] Since then, the name Astyanax fasciatus has been deemed obsolete, and multiple subspecies therein have been elevated to species rank whilst remaining in the genus Astyanax; the base species to which the name originally applied has been renamed Psalidodon fasciatus.[7]

Astyanax altior has phylogenetic affinity with congener Astyanax aeneus. Specifically, the two species have similarities in their mitochondrial genome, largely within an RNA strand called 12S rRNA, which is one of two RNA units associated with the mitochondrial ribosome. There is at least one instance of researchers successfully substituting missing 12S data from A. altior with 12S data from A. aeneus for the purpose of assessing the presence of the former in the Yucatán Peninsula, using an identification technique called DNA barcoding.[8] (DNA barcoding is currently being tested as a means of differentiating and identifying neotropical fish species.[9] 12S RNA and its companion, 16S RNA, have successfully been used in the past for taxonomic classification of animal tissues, including fish, amphibians, and mammals.)[10]

Hybridization between A. altior and A. aeneus has been recorded.[11][12] A. altior, with isolated populations and a relatively wide spread over its range, is at risk of genetic introgression, specifically with A. aeneus. Introgression is the process by which genetic material from one species is introduced into another, and the resulting interspecies offspring may replace one or both parent species in extreme cases; this is a potential cause of extinction.[6]

Etymology

editThe genus name "Astyanax" is an allusion to Astyanax, a Trojan warrior of the same name in Homer's Iliad. While the reasoning therein was not made clear in the original text, this possibly originates in the large, armor-like scales of type specimen Astyanax argentatus (which is largely considered a synonym of Astyanax mexicanus by modern taxonomists).[13] The specific name "altior" means "higher" (consider "altitude", which means "height"), and is likely in reference to the fins, which were described as "unusually high" by Hubbs.[14]

Description

editAstyanax altior reaches a maximum length of 5.75 cm (2.26 in) standard length (SL). The body is notably deep for a member of Astyanax, within the range of 37–48% SL; other species inhabiting the Yucatán never have a body depth greater than 42% SL.[15] A. altior has a dark patch on the caudal peduncle, a dark-gray or silvery lateral stripe, and a somewhat diffuse, oval-shaped humeral spot. The body color is most often gray or silver, but orange is not unknown;[16] in populations living alongside congener A. aeneus, individuals of A. altior are a brighter yellow.[6]

In the original description of A. altior, its visual similarities to congener A. aeneus were remarked upon. The main differentiating factor between the two at the time was the number of anal-fin rays, which are fewer in A. altior than A. aeneus (22 to 23 vs. 24, respectively). The original description also makes note of its sharp and "unusually high (or long)" fins.[17]

Distribution and habitat

editAstyanax altior is endemic to the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico, specifically to the northernmost third.[18] It has been collected from a variety of habitats, including both freshwater and brackish conditions, but it is most commonly cited from the cenotes therein.[19][20] It also seems to be abundant in karstic wetland systems.[11] Its type locality, a site near Progreso, has been destroyed.[1] Mangrove swamps are also a part of A. altior's habitat, though it is sensitive to the conditions therein, and mangrove swamps that have deteriorated in general health have smaller populations.[21]

Cenotes are natural sinkholes in carbonate rock that fill with water, most often referring specifically to the formations in the Yucatán Peninsula.These are either connected to an aquifer or other body of water (and thus have sufficient water cycling to maintain clear waters), or are isolated (and therefore turbid).[19] A. altior has a preference for the cenotes with clearer waters.[16] The anchialine cenotes located in Tulum are a specific example, but A. altior is generally easy to find within most cenotes in its range.[19]

Diet and ecology

editAstyanax altior is known to be omnivorous. Juveniles are more often planktivorous, and adults lean slightly towards carnivorous tendencies, though specimens will take supplemental plant materials (largely in the form of periphyton). There may be an element of cannibalism in its diet.[16]

Astyanax altior forms schools. Schooling behavior is more common in younger fish.[16] It is also known to live syntopically with congener A. aeneus in at least one cenote; this is part of why they are recognized as different valid species. Otherwise, they would likely be considered synonymous due to considerable morphological overlap, but the fact that they remain distinct when in sympatry supports their species status.[6]

Reproduction occurs during the rainy season.[6]

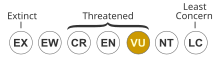

Conservation status

editAstyanax altior is listed as a vulnerable species by the IUCN. Part of this is due to its isolated ecosystems and limited range, solely found in cenotes on the Yucatán Peninsula that allow for little genetic transfer between populations. It is known to occur in at least one cenote that is a part of a protected archaeological site, Cenote Xlaká in Dzibilchaltún, but no plans are in place for A. altior as a species.[1]

It is advised that conservation efforts for A. altior include actions to protect the cenotes it inhabits. Chemical and oil contamination are of particular note, such as sunscreen from tourists or fuel leaks from hydraulic pumps. It is also important not to introduce outside species to the cenotes, as the trophic web therein is susceptible to severe damage or collapse if any of the niches are disrupted; the ecosystems are comparatively fragile, due to their isolation.[16] A. altior itself is vulnerable to introgression by members of A. aeneus, which could potentially lead to its extinction.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b c Schmitter-Soto, J.; Arroyave, J. (2019). "Astyanax altior". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T191200A1972587. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T191200A1972587.en. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Astyanax altior". FishBase. March 2023 version.

- ^ "Yucatan Tetra". Encyclopedia of Life. National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Astyanax altior Hubbs, 1936. Retrieved through: Interim Register of Marine and Nonmarine Genera on 2 March 2023.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Species related to Astyanax altior". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Schmitter Soto, Juan Jacobo (February 1998). "Diagnosis of Astyanax altior (Characidae), with a morphometric analysis of Astyanax in the Yucatan Peninsula". Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters. 8 (4). Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil: 349–358. ISSN 0936-9902. OCLC 202035972.

- ^ Astyanax fasciatus (Cuvier, 1819). Bailly, Nicolas. Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 2 March 2023.

- ^ Alter, S. Elizabeth; Arroyave, Jairo (2022-10-24). "Environmental DNA metabarcoding is a promising method for assaying fish diversity in cenotes of the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico". Metabarcoding and Metagenomics. 6: e89857. doi:10.3897/mbmg.6.89857. ISSN 2534-9708.

- ^ Milan, David T.; Mendes, Izabela S.; Damasceno, Júnio S.; Teixeira, Daniel F.; Sales, Naiara G.; Carvalho, Daniel C. (2020-10-21). "New 12S metabarcoding primers for enhanced Neotropical freshwater fish biodiversity assessment". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 17966. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1017966M. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74902-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7578065. PMID 33087755.

- ^ Yang, Li; Tan, Zongqing; Wang, Daren; Xue, Ling; Guan, Min-xin; Huang, Taosheng; Li, Ronghua (2014-02-13). "Species identification through mitochondrial rRNA genetic analysis". Scientific Reports. 4 (1): 4089. Bibcode:2014NatSR...4E4089Y. doi:10.1038/srep04089. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5379257. PMID 24522485.

- ^ a b Torres-Castro, Ivette Liliana; Vega-Cendejas, María Eugenia; Schmitter-Soto, Juan Jacobo; Palacio-Aponte, Gerardo; Rodiles-Hernández, Rocío (June 2009). "Ictiofauna de sistemas cárstico-palustres con impacto antrópico: los petenes de Campeche, México". Revista de Biología Tropical. 57 (1–2). Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Wilkens, Horst (2017). Evolution in the dark : Darwin's loss without selection. Ulrike Strecker. Berlin: Springer. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-662-54512-6. OCLC 988292884.

- ^ Astyanax argentatus Baird & Girard, 1854. Bailly, Nicolas. Retrieved through: World Register of Marine Species on 2 March 2023.

- ^ Scharpf, Christopher; Lazara, Kenneth J. (29 December 2022). "Order CHARACIFORMES: Family CHARACIDAE: Subfamily STETHAPRIONINAE (a-g)". The ETYFish Project. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ Schmitter-Soto, Juan J. (2017-06-26). "A revision of Astyanax (Characiformes: Characidae) in Central and North America, with the description of nine new species". Journal of Natural History. 51 (23–24): 1331–1424. Bibcode:2017JNatH..51.1331S. doi:10.1080/00222933.2017.1324050. ISSN 0022-2933.

- ^ a b c d e Schmitter-Soto, Juan Jacob (January 2016). Ceballos, Gerardo (ed.). Los peces dulceacuícolas de México en peligro de extinción. Fondo de Cultura Económica. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-607-16-5719-0. OCLC 1186581256. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Hubbs, Carl L. (5 February 1936). "XVII. Fishes of the Yucatan Peninsula" (PDF). Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication (457): 157–287. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- ^ Schmitter-Soto, Juan J. (2022), "Endangered Freshwater Fishes of the Yucatan Peninsula", Imperiled: The Encyclopedia of Conservation, Elsevier, pp. 597–601, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-821139-7.00085-4, ISBN 978-0-12-821139-7, retrieved 2023-03-02

- ^ a b c Schmitter-Soto, Juan Jacob (2002). "Hydrogeochemical and biological characteristics of cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula (SE Mexico)". In Alcocer, Javier; Sarma, S. S. S. (eds.). Advances in Mexican Limnology: Basic and Applied Aspects. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. pp. 215–228. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-0415-2. ISBN 978-94-010-3913-0.

- ^ Sarai, Esquivel Bobadilla (July 2011). Análisis genético de Astyanax mexicanus (characidae, teleostei, pisces) de la vertiente atlántica de México usando microsatélites (Master's thesis). Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, S.C.

- ^ Schmitter-Soto, Juan J. (2022), "Endangered Freshwater Fishes of the Yucatan Peninsula", Imperiled: The Encyclopedia of Conservation, Elsevier, pp. 597–601, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-821139-7.00085-4, ISBN 978-0-12-821139-7, retrieved 2023-03-03