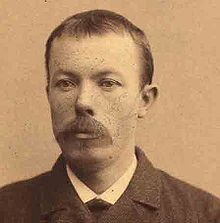

Arne Garborg (born Aadne Eivindsson Garborg) (25 January 1851 – 14 January 1924) was a Norwegian writer.

Arne Garborg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Time, Norway |

Garborg championed the use of Landsmål (now known as Nynorsk, or New Norwegian), as a literary language; he translated the Odyssey into it. He founded the weekly Fedraheimen in 1877, in which he urged reforms in many spheres including political, social, religious, agrarian, and linguistic. He was married to Hulda Garborg.

Life and career

editGarborg grew up on a farm named Garborg, near Undheim, in Time municipality at Jæren in Rogaland county. He grew up together with eight siblings. Although he was to become known as an author, it was as a newspaperman that he got his start. In 1872 he established the newspaper Tvedestrandsposten, and in 1877 the Fedraheimen, which he served as managing editor until 1892.[1] In the 1880s he was also a journalist for the Dagbladet. In 1894 he laid the ground, together with Rasmus Steinsvik, for the paper Den 17de Mai;[2] which changed its name to Norsk Tidend in 1935. As of 1898 Garborg was among the contributors of Ringeren, a political and cultural magazine established by Sigurd Ibsen.[3]

His novels are profound and gripping while his essays are clear and insightful. He was never inclined to steer clear of controversy. His work tackled the issues of the day, including the relevance of religion in modern times, the conflicts between national and European identity, and the ability of the common people to actually participate in political processes and decisions.

In 2012 the Garborg Centre opened at Bryne, Time. It is dedicated to the literature and philosophy of Arne and his wife, Hulda. Several of their homes are now turned into museums, like Garborgheimen, Labråten, Kolbotn and Knudaheio.

Bibliography

edit- Ein Fritenkjar (1878)

- Bondestudentar (1883)

- Forteljingar og Sogar (1884)

- Mannfolk (1886)

- Uforsonlige (1888)

- Hjaa ho Mor (1890)

- Kolbotnbrev (1890) (Letters)

- Trætte Mænd (1891) (published in English as Tired Men or Weary Men)

- Fred (1892) (published in English as Peace)

- Jonas Lie. En Udviklingshistorie (1893)

- Haugtussa (1895) (Poetry)

- Læraren (1896)

- Den burtkomme Faderen (1899) (published in English in 1920 as The Lost Father, translation by Mabel Johnson Leland)

- I Helheim (1901)

- Knudahei-brev (1904) (Letters)

- Jesus Messias (1906)

- Heimkomin Son (1906)

- Dagbok 1905–1923 (1925–1927) (Diary)

- Tankar og utsyn (1950) (Essays)

Quotations

edit"It is said that with money you can have everything, but you cannot. You can buy food, but not appetite; medicine but not health; knowledge but not wisdom; glitter, but not beauty; fun, but not joy; acquaintances, but not friends; servants, but not faithfulness; leisure, but not peace. You can have the husk of everything for money, but not the kernel."[4]

References

edit- ^ His friend Ivar Mortensson-Egnund edited the paper “Fedraheimen” from 1883 until 1889.

- ^ Norway's independence day.

- ^ Terje I. Leiren (Fall 1999). "Catalysts to Disunion: Sigurd Ibsen and "Ringeren", 1898-1899". Scandinavian Studies. 71 (3): 297–299. JSTOR 40920149.

- ^ Editorial. The Weekender Newspaper. Cluny, Alberta, Canada, March 4, 2005.

- The Literary Masters of Norway, with samples of their works, introduced by Carl Henrik Grøndahl and Nina Tjomsland; Tanum-Norli, Oslo 1978

External links

edit- Arne Garborg, Columbia Encyclopedia

- Digitized books and manuscripts by Garborg in the National Library of Norway

- Haugtussa at biphome.spray.se is a link to the text of Garborg's cycle of poems "Haugtussa", which celebrates the landscape of Jæren, where he grew up, and where he also built his study house "Knudaheio".

- (in Norwegian) link to all his works, at UiO.no

- Works by Arne Garborg at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Arne Garborg at the Internet Archive

- Works by Arne Garborg at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Garborg Center