The armadillo girdled lizard (Ouroborus cataphractus),[2] also commonly known as the armadillo lizard, the armadillo spiny-tailed lizard, and the golden-armadillo lizard, is a species of lizard in the family Cordylidae. The species is endemic to desert areas along the western coast of South Africa.[3] In 2011, it was moved to its own genus based on molecular phylogeny, but formerly it was included in the genus Cordylus.[2][4] It has the largest known genome of all squamates.[5]

| Armadillo girdled lizard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Namakwa, Northern Cape, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Cordylidae |

| Genus: | Ouroborus Stanley, Bauer, Jackman, Branch & Mouton, 2011 |

| Species: | O. cataphractus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ouroborus cataphractus (F. Boie, 1828)

| |

| |

| IUCN range as of 2021 | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

Description

editThe armadillo girdled lizard can be a light brown to dark brown in colouration. The underbelly is yellow with a blackish pattern, especially under the chin. Its size can range from 7.5 to 9 cm (3.0 to 3.5 in) in snout-vent length (SVL). It may grow to a maximum size of 8 in (20 cm) STL.[3]

Distribution and habitat

editO. cataphractus is endemic to the Succulent Karoo biome in the Northern and the Western Cape provinces of South Africa, where it occurs from the southern Richtersveld to the Piketberg Mountains and the southern Tankwa Karoo. It inhabits rock outcrops mountain slopes, preferably on sandstone substrate.[1]

Ecology

editDiet

editThe armadillo girdled lizard feeds mainly on small invertebrates, such as insects and spiders, but sometimes also may take plant material.[3][6] In captivity, it is commonly fed crickets. In the wild, its most common prey items are termites, especially Microhodotermes viator[3] and Hodotermes mossambicus.[6] Individuals in larger social groups tend to eat more termites than those in smaller groups[7]

Behaviour

editThe armadillo girdled lizard is diurnal. It hides in rock cracks and crevices. It lives in social groups of up to 30 to 60 individuals of all ages, but usually fewer.[3][6] Males are territorial, protecting a territory and mating with the females living there.[6]

The armadillo girdled lizard possesses an uncommon antipredator adaptation, in which it rolls into a ball and takes its tail in its mouth when frightened. In this shape, it is protected from predators by the thick, squarish scales along its back and the spines on its tail.[3] This behaviour, which resembles that of the mythical ouroboros and of the mammalian armadillo, gives it its taxonomic and English common names.[3]

Reproduction

editThe female armadillo girdled lizard gives birth to one[3] or two[6] live young; the species is one of the few lizards that does not lay eggs. The female may even feed her young, which is also unusual for a lizard. Females give birth once a year at most; some take a year off between births.

One hundred and six individuals from 27 groups were marked and recaptured regularly from May until September 2002. The group that was greater in fidelity had a greater neighbouring distance. While the group that was less in fidelity had a less neighbouring distance. The neighbouring distance correlates to the fidelity of the armadillo girdled lizard species.[8]

Males follow either a prenuptial or postnuptial reproductive cycle. The more common cycle is prenuptial with high sperm count being in the fall and winter seasons. In the postnuptial cycle, males produce the most sperm in the late summer season.[9]

Conservation

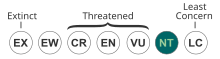

editThe species Ouroborus cataphractus is classified by the IUCN as near threatened. This is mostly due to a general cessation of collection for the pet trade, which was a significant drain on populations but is now illegal.[1][3][6] The armadillo girdled lizard is thought to be somewhat susceptible to fluctuations in its primary food source (termites), which in turn can be impacted by climatic events such as changes in rainfall patterns, as well as to habitat changes through invasive alien plant species and poor fire management.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b c d Tolley, K.A.; Alexander, G.J.; Pietersen, D.; Conradie, W.; Weeber, J. (2022). "Ouroborus cataphractus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T5333A197397829. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T5333A197397829.en.

- ^ a b c Species Ouroborus cataphractus at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cordylus cataphractus ". Arkive Archived 2010-05-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Stanley, Edward L.; Bauer, Aaron M.; Jackman, Todd R.; Branch, William R.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (2011). "Between a rock and a hard polytomy: Rapid radiation in the rupicolous girdled lizards (Squamata: Cordylidae)". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 58 (1): 53–70. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.08.024. PMID 20816817.

- ^ Saha, Anik; Bellucci, Arianna; Fratini, Sara; Cannicci, Stefano; Ciofi, Claudio; Iannucci, Alessio (2023). "Ecological factors and parity mode correlate with genome size variation in squamate reptiles". BMC Ecology and Evolution. 23 (69): 69. doi:10.1186/s12862-023-02180-4. PMC 10696768. PMID 38053023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Cordylus cataphracus". Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Van Wyk, Johannes; Mouton, P. le Fras; Shuttleworth, Cindy (2008-01-01). "Group size and termite consumption in the armadillo lizard, Cordylus cataphractus ". Amphibia-Reptilia. 29 (2): 171–176. doi:10.1163/156853808784125045. ISSN 1568-5381.

- ^ Flemming, A.F.; Costandius, E.; Mouton, P.L.N. (2006). "The effect of intergroup distance on group fidelity in the group-living Lizard, Cordylus cataphractus". African Journal of Herpetology. 55 (1): 61–68. doi:10.1080/21564574.2006.96355 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Flemming, Alexander F.; Mouton, P. Le Fras N. (December 2002). "Reproduction in a Group-Living Lizard, Cordylus cataphractus (Cordylidae), from South Africa". Journal of Herpetology. 36 (4): 691–696. doi:10.1670/0022-1511(2002)036[0691:RIAGLL]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0022-1511.

Further reading

edit- Boie F (1828). "Über eine noch nichte beschriebene Art von Cordylus Gronov. Cordylus cataphractus Boie ". Nova Acta Academiae Caesareae Leopoldino-Carolinae (Halle) 14 (1): 139-142. (Cordylus cataphractus, new species). (in German).

- Boulenger GA (1885). Catalogue of the Lizards in the British Museum (Natural History). Second Edition. Volume III. Iguanidæ, Xenosauridæ, Zonuridæ ... London: Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History). (Taylor and Francis, printers). xiii + 497 pp. + Plates I-XXIV. (Zonurus cataphractus, pp. 255–256).

- Branch, Bill (2004). Field Guide to Snakes and other Reptiles of Southern Africa. Third Revised edition, Second impression. Sanibel Island, Florida: Ralph Curtis Books. 399 pp. ISBN 0-88359-042-5. (Cordylus cataphractus, pp. 186–187 + Plate 68).