This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2024) |

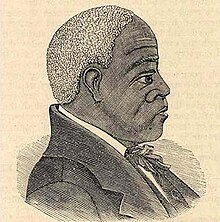

Andrew Bryan (1737–1812) founded Bryan Street African Baptist Church,[1] affectionately called the Mother Church of Black Baptists, and First African Baptist Church of Savannah in Savannah, Georgia,[2][3] the first black Baptist churches to be established in America.[4] Bryan was formerly enslaved by Jonathan Bryan.[5]

Andrew Bryan was born in 1737 in Goose Creek, South Carolina, to slave parents. He married a woman named Hannah. Bryan converted to Christianity through the preaching of George Liele. After Liele left Savannah for a mission to Jamaica, Bryan began to preach. He was imprisoned twice for preaching to enslaved people, but he continued to do so. He was also severely whipped but was noted for enduring the suffering as Jesus Christ had done.[6] Bryan established the church which would eventually become known as First African Baptist Church, and it grew from sixty-nine members in 1788 to about seven hundred by 1800.[7]

Origin and family

editAndrew Bryan was born in 1737 in the small town of Goose Creek, South Carolina. Bryan was born on a plantation called Brampton, owned by Jonathan Bryan. Brampton was known as a productive rice plantation. His father was a man named Caesar, who was enslaved along with Bryan. He was a mixture of black and white. Andrew served as a coachman and a body servant to Jonathan. Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (S.P.G.) was an organization that cared for British colonists in religious matters and supported the spiritual needs of Indians and enslaved people. The S.P.G. organization influenced Bryan to become a religious leader. He had a brother by the name of Sampson Bryan. Hannah Bryan was the wife of Bryan. It was believed that he had a daughter as well.

The beginning of preaching

editWhile growing up on the Brampton plantation, Bryan came across a man named George Liele. Liele was the first African American to be ordained and travel out of the country. Bryan and Liele became good friends and started preaching alongside each other. In 1783, Bryan and his wife were baptized along with some other enslaved people. Abraham Marshall and Jesse Peters baptized 45 people who followed Bryan's teachings. Those 45 people regularly organized and then became his congregation. Bryan was ordained and became the pastor of the first Baptist church in Savannah, Georgia. Sampson was the first deacon of the church. Bryan would preach along the Savannah River. Liele went away to Jamaica, and Bryan took over the churches that Liele would preach at, which caused an expansion in Bryan's congregation. One of these locations was owned by Edward Davis in Yamacraw. Davis encouraged Bryan to build a religious place in the village of Yamacraw. The gatherings at the village of Yamacraw got so big that the white community thought it was a plot of rebellion.

Service interruptions and arrest

editAndrew Bryan became so good at preaching that many people attended his services in the village of Yamacraw. The white community did not like that there were a lot of African-American people gathering for Bryan's services. The enslavers did not want the people they enslaved to listen to Bryan because they believed that he was plotting a rebellion. Whites harassed the enslaved people who did attend the services. The enslaved people were punished with whipping, shackling, hanging, beating, burning, and imprisonment. The church services were interrupted constantly by the whites. Bryan was accused of plotting a rebellion, so he was beaten and thrown in jail. Sampson was also thrown in jail along with Bryan. Jonathan Bryan and other plantation owners protested the arrest of Andrew Bryan. The Justice of the Inferior Court of Chatham County analyzed the case, resulting in Bryan and Samson being found innocent and released. After they were released, Bryan returned to preaching at Jonathan Bryan's barn from sunrise to sunset.

Expansion and ending

editWhile preaching in the barn on the Brampton plantation, Bryan's following continued to increase. Several prominent white males supported Bryan and his preachings. In 1788, the First Baptist Church got certified, and Jonathan Bryan died and left Andrew Bryan 95 pounds sterling. Bryan used 50 pounds to buy his freedom from William Bryan, Jonathan Bryan's brother. On June 1, 1790, with 27 pounds of sterling, he bought property from Thomas Gibbons that became a place for a new church. William Bryan and James Whitfield bought land for Bryan and his family to live on. In 1805, the first African Baptist church, Savannah Baptist church, and Newington Baptist Church became the Savannah River Baptist Association. Contributions from Bryan allowed this to happen. Bryan pastored for 24 years and died at 92 on October 6, 1812. He is interred in Whitefield Square in Savannah.[8]

Notes

edit- ^ Jeff (2009-05-13). "Thoughts and Theology: The Rev. Andrew Bryan 1737-1812". Thoughts and Theology. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ "Africans in America: Andrew Bryan". WGBH Educational Foundation.

- ^ Martin, Sandy Dwayne. "Andrew Bryan (1737-1812)". Georgia Humanities Council and the University of Georgia Press.

- ^ "Africans in America: First African Baptist Church of Savannah". WGBH Educational Foundation.

- ^ Alan Gallay (2007). The Formation of a Planter Elite: Jonathan Bryan and the Southern Colonial Frontier. University of Georgia Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8203-3018-1.

- ^ Davis, John W. (1918). "George Liele and Andrew Bryan, Pioneer Negro Baptist Preachers". Journal of Negro History. 3 (2): 119–127. doi:10.2307/2713485. JSTOR 2713485. S2CID 150092032.

- ^ Williams, David S. (2008). From Mounds to Megachurches: Georgia's Religious Heritage. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0820336381.

- ^ Whitefield Square – Savannah.com

- ^ Bardolph, Richard (1955-01-01). "Social Origins of Distinguished Negroes, 1770-1865: Part I". The Journal of Negro History. 40 (3): 211–249. doi:10.2307/2715950. JSTOR 2715950. S2CID 150268520.

- ^ Davis, John W. (1918-01-01). "George Liele and Andrew Bryan, Pioneer Negro Baptist Preachers". The Journal of Negro History. 3 (2): 119–127. doi:10.2307/2713485. JSTOR 2713485. S2CID 150092032.

- ^ Jandrlich, Michael (November 1990). "Andrew Bryan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-19. Retrieved 2017-04-24.