Albert Spalding (August 15, 1888 – May 26, 1953) was an internationally recognized American violinist and composer.[1]

Albert Spalding | |

|---|---|

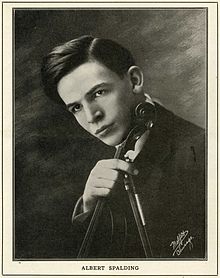

Spalding in 1915 | |

| Born | August 15, 1888 |

| Died | May 26, 1953 (aged 64) |

Biography

editSpalding was born in Chicago, Illinois on August 15, 1888. His mother, Marie Boardman, was a contralto and pianist.[2] His father, James Walter Spalding, and uncle, Hall-of-Fame baseball pitcher Albert Goodwill "Al" Spalding, created the A.G. Spalding sporting goods company.

Spalding studied the violin privately in Manhattan, New York City and Florence, Italy, before later moving on to the conservatories in Paris and Bologna, graduating from the latter with honors at fourteen years old. Following his debut at the Nouveau Théâtre in Paris on June 6, 1906, he played in the principal towns of France, Austria, Germany, Italy, and England.[3] His first American appearance as soloist came with the New York Symphony on November 8, 1908. Spalding received strongly opposing critical responses to his debut playing of the Violin Concerto No. 3 by Camille Saint-Saëns. Although the New-York Tribune accused him of "rasping, raucous, snarling, unmusical sounds," Walter Damrosch (who conducted the performance) announced him as "the first great instrumentalist this country has produced."[4] A year later he soloed with the Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra when that orchestra toured the United States. In 1916, he was recognized as a national honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia, the national fraternity for men in music. Thomas Edison analyzed Spalding’s tone with electronic equipment and found it to be the purest of any living violinist he had heard; this led to a twenty-year ‘contract’ during which Spalding made over a hundred records. His burgeoning career was soon interrupted by World War I.[4] During the war Spalding served in the United States Army Air Service (at one point as aide-de-camp to then-Congressman Fiorello La Guardia) and would eventually be awarded the Cross of the Crown of Italy.[5]

Not long after his return to the United States, he married Mary Vanderhoef Pyle on July 19, 1919, in Ridgefield, Connecticut. French violinist Jacques Thibaud and Andre Benoist, Spalding's accompanist, provided the music for the ceremony.[6] In 1920, Spalding appeared on the European tour of the New York Symphony. In 1922, he became the first American violinist to appear with the Paris Conservatory Orchestra; a year later he was the first American to serve on a jury at the Paris Conservatory, helping to award prizes to the graduating class of violinists. In February 1941, he premiered the violin concerto of Samuel Barber.[7]

Upon the United States' involvement in World War II, Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle successfully urged Spalding to accept an assignment with the Office of Strategic Services. He was posted to London, for six weeks, and then served in North Africa until he was ordered to Naples where he was attached to the Psychological Warfare Division of SHAEF.[8] In 1944, Spalding gave a legendary concert to thousands of terrified refugees stranded in a cave near Naples during a bombing raid.[2]

Following a concert in New York on May 26, 1950, Spalding announced his retirement from the concert stage. Thereafter, he taught master classes at Boston University College of Music and, in the winter months, at Florida State University. His last recital, with pianist Jules Wolffers, at Boston University on 15 May 1953 was preserved on record (LP 33 rpm, Halo 50296 | ℗1957). Ten days later he died in Manhattan, New York City, at the age of 64.[citation needed]

Legacy

editHe was a National Patron of Delta Omicron, an international professional music fraternity.[9]

Works

editSpalding wrote several musical compositions including a suite for orchestra, two violin concerti and a String Quartet in E Minor.[1] He also wrote an autobiography, Rise to Follow, published in 1943. His novel about Giuseppe Tartini, A Fiddle, a Sword, and a Lady, appeared in 1953.

Recordings

editIndividual 78 RPM sides and album sets

editDuring the 78 era, when the maximum capacity of a single ordinary record side or cylinder was less than five minutes, Spalding recorded extensively for Edison Records, with some issues on cylinders and many more on diamond discs. Most featured short works or encore pieces that could fit on a single record side. These recordings were all by the acoustical process, as well as vertically-cut, through 1925, but he made his first electrical recordings in 1926 for Brunswick Records using that company's problematic "Light-Ray" system. After his unsatisfactory experience with Brunswick, Spalding went back to Edison and made some electrical Edison hill-and-dale Diamond Discs as well as a very few Edison "Needle Cut" lateral recordings in late 1928. These were much better recorded than Spalding's Brunswicks, but the Diamond Discs sold as scantily as the rest of Edison's product in that period, and the "Needle-Cut" discs were issued only for a very short time—from August to November 1929—and are exceedingly rare today. Following the Edison company's demise in November 1929, he recorded a handful of more extended works broken across multiple sides for RCA Victor Records.

Long playing records

editSpalding's role as a leading Edison artist secured him representation on the first long-playing records: Edison's commercially ill-fated long-playing diamond discs, introduced in 1926, which were capable of playing up to 20 minutes per side at 80 RPM. Because, like all material on these pioneering records, his selections were dubbed from standard diamond disc masters, they represented the same short pieces in his standard catalogue.

At the end of his life, Spalding again appeared on LP records, this time budget issues by small labels, but performing more substantial fare. Particularly of note are his accounts of the Beethoven and Brahms violin concerti recorded for Remington Records in Vienna, Austria's Brahms Hall in 1952, his last recording sessions. In both, Wilhelm Loibner conducted an ensemble billed as the Austrian Symphony Orchestra. For the same company Spalding earlier recorded the three Brahms violin sonatas with pianist Ernő Dohnányi; selected Brahms Hungarian Dances with pianists Dohnányi and Anthony Kooiker,[10] who toured with Spalding for four years; and a collection of music by Tartini, Corelli, and J.S. Bach, some in his own arrangements, with Kooiker. A recital of short pieces issued on the Halo label, with accompanist Jules Wolffers, captures Spalding's voice as he announces two of the works.

Notes

edit- ^ a b Albert Spalding – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ a b The Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics

- ^ "Albert Spalding: 'The Greatest American Violinist'".

- ^ a b "Albert Spalding- Bio, Albums, Pictures – Naxos Classical Music".

- ^ "No Silver Spoon". Time. February 2, 1931. Archived from the original on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- ^ "Miss Pyle Married to Albert Spalding" (PDF). The New York Times. July 20, 1919. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Meet the Music - Featured Work". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Albert Spalding". Archived from the original on 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Delta Omicron Archived 2010-01-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rec: 1950 / 12", 33 rpm, Remington RLP-199-23 / ℗1951

References

edit- David Ewen, Encyclopedia of Concert Music. New York; Hill and Wang, 1959.

- Biographical sketch and LP discography on The Remington Site, http://www.soundfountain.org/rem/remspalding.html.

- Biographical sketch, reprinting album liner notes from Allegro record 1675, at http://www.4music.net/spalding.html.

- The Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, at http://ccrma.stanford.edu/groups/edison/exhibit/exhibit-1.html