Akidnognathidae is an extinct family of therocephalian therapsids from the Late Permian and Early Triassic of South Africa, Russia and China. The family includes many large-bodied therocephalians that were probably carnivorous, including Moschorhinus and Olivierosuchus. One akidnognathid, Euchambersia, may even have been venomous. Akidnognathids have robust skulls with a pair of large caniniform teeth in their upper jaws. The family is morphologically intermediate between the more basal therocephalian group Scylacosauridae and the more derived group Baurioidea.

| Akidnognathidae Temporal range: Late Permian - Early Triassic

| |

|---|---|

| |

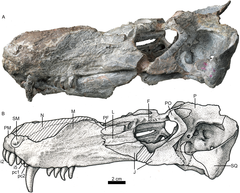

| Holotype skull of Jiufengia jiai | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida |

| Clade: | †Therocephalia |

| Clade: | †Eutherocephalia |

| Family: | †Akidnognathidae Nopcsa, 1928 |

| Genera | |

|

List

| |

| Synonyms | |

Research history

editThe first known fossils of akidnognathids consists of two skulls which were discovered during a series of excavations carried out from 1899 until 1914 by Vladimir Amalitsky and his companion Anna P. Amalitsky in the Northern Dvina, in present-day European Russia. In an article published posthumously in 1922, Amalitsky established a new taxon of therocephalians under the name Anna petri, in honor of his companion. In his description he judges it to be similar to Scylacosaurus.[1] In 1963, Oskar Kuhn proposed changing the name of the genus to Annatherapsidus, seeing that Anna was an already preoccupied taxon. Currently, Annatherapsidus is the only akidnognathid known from Russian territory.[2]

The first akidnognathid to be described was the type genus Akidnognathus, named in 1918 by Sidney Henry Haughton from a skull discovered by reverend John H. Whaits in the Beaufort Group, South Africa. The specimen comes more precisely from the upper Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone, within the Karoo Supergroup.[3] It is in the Karoo supergroup where the majority of known akidnognathids will be identified,[2] with at least two additional genera, namely Euchambersia and Proalopecopsis, also from the upper Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone.[4]

Akidnognathids were historically only reported from Russia and South Africa, but it was from 2017 that paleontologists Jun Liu and Fernando Abdala described several taxa from the Naobaogou Formation, in Inner Mongolia, China, from several fossils collected on this fossil site since 2009.[2][5][6] Among these described taxa, the two authors identify a second species of Euchambersia, a genus that was previously reported only in South Africa.[6]

Classification

editThe first family-level name used to classify an akidnognathid was Euchambersidae, erected by South African paleontologist Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra in 1934,[7] in reference for the genus Euchambersia, which is possibly one of the oldest known venomous tetrapods.[8] Noting that the taxon is written in improper Latin, German paleontologist Friedrich von Huene changed the spelling of the name to Euchambersiidae in 1940.[9] The taxon Akidnognathidae was first named in 1954 by South African paleontologists Haughton and Adrian Smuts Brink,[10] basing their proposal on Akidnognathinae, which was created in 1928 by Ferenc Nopcsa. Nopcsa originally established Akidnognathinae as a subfamily of the Scaloposauridae,[11] which currently appears to be a wastebasket taxon. In the classification of Haughton and Brink, the akidnognathids includes several therocephalians still recognized as such as well as several other genera, now classified as scylacosaurids.[12] English and American paleontologists D. M. S. Watson and Alfred Romer moved many of these therocephalians into the family Whaitsiidae in 1956,[13] although many were moved back to Akidnognathidae in later years.[14][15][12]

In 1974, Christiane Mendrez established the family Moschorhinidae, while recognizing three subfamilies making it up, namely Annatherapsidinae, Moschorhininae and Euchambersiinae.[14] In 1975, the same author proposed another name to designate the group, Annatherapsididae, although she maintained the validity of the three subfamilies previously cited.[16] In their phylogenetic revision of therapsids published in 1986, James Hopson and Herb Barghusen supported Mendrez's hypothesis that the group included three subfamilies, but both authors preferred to use the name Euchambersiidae instead.[17] While the name Euchambersiidae may have priority over Akidnognathidae because it was named first, Akidnognathidae is currently considered as the valid name because it is based on the first named genus of the group, Akidnognathus, this latter having been named in 1918 while Euchambersia was named in 1931.[12] It is on the basis of this affirmation that this name has achieved wider acceptance within the scientific literature.[18][19][12] In 1974, Leonid Petrovich Tatarinov proposed uniting the Akidnognathidae (then named Annatherapsididae), the Whaitsiidae and the Moschowhaitsiidae within a superfamily called Whaitsioidea.[20] Multiple authors have disagreed with this proposition,[14][17][21] but others like Mikhail Ivakhnenko in 2008 and Adam Huttenlocker in 2009, share Tatarinov's point of view.[22][12] However, phylogenies led by Huttenlocker and Christian Sidor found that the Akidnognathidae was instead closest to the Chthonosauridae, with the two forming the sister group to the group containing the Whaitsioidea and the Baurioidea.[23] Subsequent classifications published after this study tend to follow this pattern.[6]

The cladogram below follows a phylogenetic analysis led by Jun Liu and Fernando Abdala in 2022,[6] largely sharing the topology recovered by Huttenlocker and Sidor:[23]

Distribution

editAkidnognathids are known from various fossils identified in Russia, South Africa and China. However, a skull from an undescribed taxon was identified in the Fremouw Formation, Antarctica, and is dated to the Lower Triassic.[24]

References

edit- ^ Amalitzky, V. (1922). "Diagnoses of the new forms of vertebrates and plants from the Upper Permian on North Dvina". Bulletin de l'Académie des Sciences de Russie. 16 (6): 329–340.

- ^ a b c Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2017). "The tetrapod fauna of the upper Permian Naobaogou Formation of China: 1. Shiguaignathus wangi gen. et sp. nov., the first akidnognathid therocephalian from China". PeerJ. 5: e4150. doi:10.7717/peerj.4150. PMC 5723136. PMID 29230374.

- ^ Haughton, S. H. (1918). "Some new carnivorous Therapsida, with notes upon the braincase in certain species". Annals of the South African Museum. 12: 175–216.

- ^ Smith, R.; Rubidge, B.; van der Walt, M. (2011), "Therapsid Biodiversity Patterns and Palaeoenvironments of the Karoo Basin, South Africa", in Chinsamy-Turan, A. (ed.), Forerunners of Mammals: Radiation, Histology, Biology, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, pp. 31–64, ISBN 978-0-253-00533-5

- ^ Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2019). "The tetrapod fauna of the upper Permian Naobaogou Formation of China: 3. Jiufengia jiai gen. et sp. nov., a large akidnognathid therocephalian". PeerJ. 7: e6463. doi:10.7717/peerj.6463. PMC 6388668. PMID 30809450.

- ^ a b c d Liu, J.; Abdala, F. (2022). "The emblematic South African therocephalian Euchambersia in China: a new link in the dispersal of late Permian vertebrates across Pangea". Biology Letters. 18 (7): 20220222. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2022.0222. PMC 9278400. PMID 35857894.

- ^ Boonstra, L. D. (1934). "A contribution to the morphology of the mammal-like reptiles of the suborder Therocephalia". Annals of the South African Museum. 31: 215–267.

- ^ Benoit, J.; Norton, L. A.; Manger, P. R.; Rubidge, B. S. (2017). "Reappraisal of the envenoming capacity of Euchambersia mirabilis (Therapsida, Therocephalia) using μCT-scanning techniques". PLOS ONE. 12 (2): e0172047. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1272047B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172047. PMC 5302418. PMID 28187210.

- ^ von Huene, F. (1940). "Die Saurier der Karroo, Gondwana und verwandten Ablagerungen in faunistischer, biologischer und phylogenetischer Hinsicht" [The reptiles of the Karroo, Gondwana and related deposits in faunistic, biological and phylogenetic terms]. Neues Jahrbuch für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Beilage-Band (in German). 83: 246–347. OCLC 600936687.

- ^ Haughton, S. H.; Brink, A. S. (1954). "A bibliographical list of Reptilia from the Karroo beds of Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 2: 1–187.

- ^ Nopcsa, F. (1928). "The genera of reptiles" (PDF). Palaeobiologica. 1: 163–188.

- ^ a b c d e Huttenlocker, A. (2009). "An investigation into the cladistic relationships and monophyly of therocephalian therapsids (Amniota: Synapsida)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 157 (4): 865–891. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00538.x. S2CID 84603632.

- ^ Watson, D. M. S.; Romer, A. S. (1956). "A classification of therapsid reptiles". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology. 111: 37–89. OCLC 249699529.

- ^ a b c Mendrez, C. H. (1974). "Étude du crâne d'un jeune spécimen de Moschorhinus kitchingi Broom, 1920 (?Tigrisuchus simus Owen, 1876), Therocephalia, Pristerosauria, Moschorhinidae d'Afrique Australe (Remarques sur les Moschorhinidae et les Whaitsiidae)" [Study of the skull of a young specimen of Moschorhinus kitchingi Broom, 1920 (?Tigrisuchus simus Owen, 1876), Therocephalia, Pristerosauria, Moschorhinidae from Southern Africa (Remarks on Moschorhinidae and Whaitsiidae)]. Annals of the South African Museum (in French). 64: 71–115.

- ^ Durand, J. F. (1991). "A revised description of the skull of Moschorhinus (Therapsida, Therocephalia)". Annals of the South African Museum. 99: 381–413.

- ^ Mendrez, C. H. (1975). "Principales variations du palais chez les thérocéphales Sud-Africains (Pristerosauria et Scaloposauria) au cours du Permien Supérieur et du Trias Inférieur" [Main variations of the palate in South African therocephalians (Pristerosauria and Scaloposauria) during the Upper Permian and Lower Triassic]. Colloque International C.N.R.S. Problèmes Actuels de Paléontologie-Évolution des Vertébrés (in French). 218: 379–408.

- ^ a b Hopson, J. A.; Barghusen, H. R. (1986), "An analysis of therapsid relationships", in Hotton III, N.; MacLean, P. D.; Roth, J. J.; Roth, E. C. (eds.), The Ecology and Biology of Mammal-like Reptiles, Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 83–106, ISBN 978-0-874-74519-1, JSTOR 4523181

- ^ Rubidge, B. S.; Sidor, C. A. (2001). "Evolutionary Patterns Among Permo-Triassic Therapsids". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 32: 449–480. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.32.081501.114113. S2CID 51563288.

- ^ Sigurdsen, T. (2006). "New features of the snout and orbit of a therocephalian therapsid from South Africa" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 63–75.

- ^ Tatarinov, L. P. (1974). Териодонты СССР [Theriodonts of the USSR] (in Russian). Vol. 143. Trudy Paleontologicheskogo Instituta, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. pp. 1–226.

- ^ Huttenlocker, A. K.; Smith, R. M. H. (2017). "New whaitsioids (Therapsida: Therocephalia) from the Teekloof Formation of South Africa and therocephalian diversity during the end-Guadalupian extinction". PeerJ. 5: e3868. doi:10.7717/peerj.3868. PMC 5632541. PMID 29018609.

- ^ Ivakhnenko, M. F. (2008). "The First Whaitsiid (Therocephalia, Theromorpha)". Paleontological Journal. 42 (4): 409–413. doi:10.1134/S0031030108040102. S2CID 140547244.

- ^ a b Huttenlocker, A. K.; Sidor, C. A. (2016). "The first karenitid (Therapsida, Therocephalia) from the upper Permian of Gondwana and the biogeography of Permo-Triassic therocephalians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (4): e1111897. Bibcode:2016JVPal..36E1897H. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1111897. JSTOR 24740259. S2CID 130994874.

- ^ Huttenlocker, A. K.; Sidor, C. A. (2012). "Taxonomic Revision of Therocephalians (Therapsida: Theriodontia) from the Lower Triassic of Antarctica". American Museum Novitates. 3728: 1–19. doi:10.1206/3738.2. S2CID 55745212.