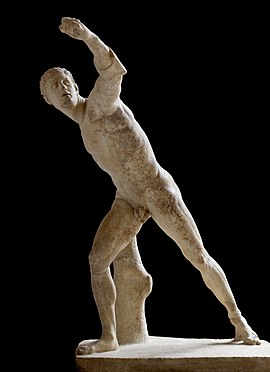

The Borghese Gladiator is a Hellenistic life-size[1] marble sculpture portraying a swordsman, created at Ephesus about 100 BC, now on display at the Louvre.

| Borghese Gladiator | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Agasias of Ephesus (signature) |

| Year | c.100 BC |

| Type | Marble |

| Dimensions | 199 cm (78 in) |

| Location | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

Sculptor

editThe sculpture is signed on the pedestal by Agasias, son of Dositheus, who is otherwise unknown. It is not quite clear whether the Agasias who is mentioned as the father of Heraclides is the same person. Agasias, son of Menophilus may have been a cousin.[2]

Rediscovery

editIt was found before 1611, in the present territory of Anzio south of Rome, among the ruins of a seaside palace of Nero on the site of the ancient Antium. From the attitude of the figure it is clear that the statue represents not a gladiator, but a warrior contending with a mounted combatant. In the days when antique sculptures gained immediacy by being identified with specific figures from history or literature,[3] Friedrich Thiersch conjectured that it was intended to represent Achilles fighting with the mounted Amazon, Penthesilea.[4]

The sculpture was added to the Borghese collection in Rome. At the Villa Borghese it stood in a ground-floor room named for it, redecorated in the early 1780s by Antonio Asprucci. Camillo Borghese was pressured to sell it to his brother-in-law, Napoleon Bonaparte, in 1807; it was taken to Paris when the Borghese collection was acquired for the Louvre,[5] where it now resides.

Misnamed a gladiator due to an erroneous restoration, it was among the most admired and copied works of antiquity in the eighteenth century, providing sculptors a canon of proportions. A bronze cast was made for Charles I of England (now at Windsor), and another by Hubert Le Sueur was the centrepiece of Isaac de Caus' parterre at Wilton House;[6] that version was given by the 8th Earl of Pembroke to Sir Robert Walpole and remains the focal figure in William Kent's Hall at Houghton Hall, Norfolk. Other copies can be found at Petworth House, at Castle Howard, and in the Green Court at Knole. Originally a copy was also located in Lord Burlington's garden at Chiswick House and later relocated to the gardens at Chatsworth in Derbyshire. In the United States, a copy of "The Gladiator at Montalto"[7] was among the furnishings of an ideal gallery of instructive art imagined by Thomas Jefferson for Monticello.[8]

In painting

edit- Having seen the sculpture on his Italian travels, Rubens included a figure of Fury in the same pose (seen from behind) in one of the scenes of his allegorical Palais de Luxembourg cycle of paintings for Marie de' Medici, the Conclusion of the Peace at Angers, conserved at the Louvre; the figure of Fury is bottom right.[9]

- The figure in the water (Brook Watson) in Watson and the Shark by John Singleton Copley is based on the sculpture's pose.

- It was known, although not in the French national collection, when Ménageot included it in the background of his The Death of Leonardo da Vinci in the arms of Francis I (1781); indeed, he probably saw it at the Villa Borghese during his stay at the French Academy in Rome from 1769 to 1774. However, it was an anachronism in such a setting since Leonardo died in 1519, about ninety years before the statue was discovered.

- The stance and attitude of the warriors in Thomas Chambers's Two of the Natives of New Holland, Advancing to Combat (based on a drawing by Sydney Parkinson and illustrating his posthumous A Journal of a Voyage to the South Seas), a typical engraving in the noble savage ideal, is said to have been based upon the Borghese Gladiator.

- The headless statue in Thomas Cole's 1836 painting Destruction (the fourth painting in his The Course of Empire series) is based on the Borghese warrior.[10]

- The pose of Phineas in Luca Giordano's c. 1660 painting Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone in the National Gallery, London appears to mirror the Borghese Gladiator.[11]

Notes

edit- ^ Height 1.99 m.

- ^ Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). "Agasias". New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ The phenomenon is noted by Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, Taste and the Antique: the Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 (Yale University Press), 1981, who offer numerous examples of fanciful 16th to 18th-century identifications.

- ^ Friedrich Thiersch, Epochen der bildenden Kunst, 1816–1825.

- ^ Inventaire MR 224 (n° usuel Ma 527)

- ^ A copy of the Borghese Gladiator in a similar central position in a Dutch garden, appears in a painting by Pieter de Hooch in the Royal Collection (Lionel Cust, "Notes on Pictures in the Royal Collections-XXVIII. Two Paintings by Pieter de Hooch", The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 25 (July 1914: 205–207, illus. pl. 1).

- ^ Possibly referring to a statue that used to stand in the large hall of Sixtus V's Villa Montalto in Rome, described in the artist Willem Schellinks' Dagh-Register, an unpublished manuscript describing his travels in 1646 and 1661–1665, (Royal Library, Copenhagen, NKS370, vol. II, 718.) as "een statue van den Gladiator, swart marmer", "a statue of the Gladiator, black marble"

- ^ Seymour Howard, "Thomas Jefferson's Art Gallery for Monticello" The Art Bulletin 59. 4 (December 1977: 583–600); see Appendix B note 8.

- ^ Louvre catalogue entry

- ^ The Course of Empire-Destruction Archived April 15, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ "Luca Giordano | Perseus turning Phineas and his Followers to Stone | NG6487 | National Gallery, London".

References

edit- Louvre catalogue

- Two copies at the Louvre here and here.

- Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny, 1981. Taste and the Antique: the Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 (Yale University Press) Cat. no. 43, pp. 221–24.

- Lestache copy

- Selected Works[permanent dead link] on the Louvre's web site

- The Villa Borghese in 1807: a 3D reconstruction of the decorated facades Archived 2019-09-14 at the Wayback Machine on the Louvre's web site

- Jean-Galbert Salvage. Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux beaux arts. (Paris, 1812) in the US National Library of Medicine's Digital Collections