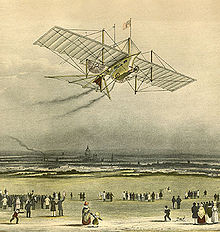

The aerial steam carriage, also named Ariel, was a flying machine patented in England in 1842 that was supposed to carry passengers into the air. It was, in practice, incapable of flight since it had insufficient power from its heavy steam engine to fly. A more successful model was built in 1848 which was able to fly for small distances within a hangar. The aerial steam carriage was significant because it was a transition from glider experimentation to powered flight experimentation.

Specifications

editThe Ariel was to be a monoplane with a wing span of 150 feet (46 m), weigh 3,000 lb (1,400 kg) and was to be powered by a specially designed lightweight steam-powered engine producing 50 hp (37 kW).[1] The wing area was to be 4,500 sq ft (420 m2)., with the tail another 1500, yielding a very low wing loading.[2] The inventors hoped that the Ariel would achieve a speed of 50 mph, and carry 10–12 passengers up to 1,000 miles (1,600 km).[3] The plan was to launch it from an inclined ramp. The undercarriage was a 3-wheel design.

British patent 9478

editWilliam Samuel Henson (1812–1888) and John Stringfellow (1799–1883) received British patent 9478 in 1842.

In order that the description hereafter given be rendered clear, I will first shortly explain the principle on which the machine is constructed. If any light and flat or nearly flat article be projected or thrown edgewise in a slightly inclined position, the same will rise on the air till the force exerted is expended, when the article so thrown or projected will descend; and it will readily be conceived that, if the article so projected or thrown possessed in itself a continuous power or force equal to that used in throwing or projecting it, the article would continue to ascend so long as the forward part of the surface was upwards in respect to the hinder part, and that such article, when the power was stopped, or when the inclination was reversed, would descend by gravity aided by the force of the power contained in the article, if the power be continued, thus imitating the flight of a bird. Now, the first part of my invention consists of an apparatus so constructed as to offer a very extended surface or plane of a light yet strong construction, which will have the same relation to the general machine which the extended wings of a bird have to the body when a bird is skimming in the air; but in place of the movement or power for onward progress being obtained by movement of the extended surface or plane, as is the case with the wings of birds, I apply suitable paddle-wheels or other proper mechanical propellers worked by a steam or other sufficiently light engine, and thus obtain the requisite power for onward movement to the plane or extended surface; and in order to give control as to the upward and downward direction of such a machine I apply a tail to the extended surface which is capable of being inclined or raised, so that when the power is acting to propel the machine, by inclining the tail upwards, the resistance offered by the air will cause the machine to rise on the air; and, on the contrary, when the inclination of the tail is reversed, the machine will immediately be propelled downwards, and pass through a plane more or less inclined to the horizon as the inclination of the tail is greater or less; and in order to guide the machine as to the lateral direction which it shall take, I apply a vertical rudder or second tail, and, according as the same is inclined in one direction or the other, so will be the direction of the machine.

Aerial Transit Company

editWilliam Samuel Henson, John Stringfellow, Frederick Marriott, and D.E. Colombine, incorporated as the "Aerial Transit Company" in 1843 in England, with the intention of raising money to construct the flying machine. Henson built a scale model of his design, which made one tentative steam-powered "hop" as it lifted or bounced, off its guide wire. Attempts were made to fly the small model, and a larger model with a 20-foot (6.1 m) wing span, between 1844 and 1847, without success.

The company planned "to convey letters, goods and passengers from place to place through the air", according to the patent.[1]

In an attempt to gain investors and support in Parliament, the company engaged in a major publicity campaign using images of the Ariel in exotic locales, but the company failed to gain the needed investment. There was speculation in the press about whether the Ariel was a hoax or fraud.

Stringfellow's son wrote the following:

My father had constructed another small model which was finished early in 1848, and having the loan of a long room in a disused lace factory, early in June the small model was moved there for experiments. The room was about 22 yards (20 m) long and from 10 to 12 feet (3.7 m) high. The inclined wire for starting the machine occupied less than half the length of the room and left space at the end for the machine to clear the floor. In the first experiment the tail was set at too high an angle, and the machine rose too rapidly on leaving the wire. After going a few yards it slid back as if coming down an inclined plane, at such an angle that the point of the tail struck the ground and was broken. The tail was repaired and set at a smaller angle. The steam was again got up, and the machine started down the wire, and, upon reaching the point of self-detachment, it gradually rose until it reached the farther end of the room, striking a hole in the canvas placed to stop it. In experiments the machine flew well, when rising as much as one in seven. The late Reverend J. Riste, Esquire, lace manufacturer, Northcote Spicer, Esquire, J. Toms, Esquire, and others witnessed experiments. Mister Marriatt, late of the San Francisco News Letter brought down from London Mister Ellis, the then leasee of Cremorne Gardens, Mister Partridge, and Lieutenant Gale, the aeronaut, to witness experiments. Mister Ellis offered to construct a covered way at Cremorne for experiments. Mr Stringfellow repaired to Cremorne, but not much better accommodations than he had at home were provided, owing to unfulfilled engagement as to room. Mister Stringfellow was preparing for departure when a party of gentlemen unconnected with the Gardens begged to see an experiment, and finding them able to appreciate his endeavours, he got up steam and started the model down the wire. When it arrived at the spot where it should leave the wire it appeared to meet with some obstruction, and threatened to come to the ground, but it soon recovered itself and darted off in as fair a flight as it was possible to make at a distance of about 40 yards (37 m), where it was stopped by the canvas. Having now demonstrated the practicability of making a steam-engine fly, and finding nothing but a pecuniary loss and little honour, this experimenter rested for a long time, satisfied with what he had effected. The subject, however, had to him special charms, and he still contemplated the renewal of his experiments.

Ariel depictions and references

edit- The Ariel appears on a number of stamps from different countries, usually as part of aviation history series.

- London Airport's (later Heathrow) first purpose-built hotel was named ‘The Ariel’ in honour of Henson and Stringfellow's design (spellings vary). As a March 1962 brochure explained “In a sense [Henson and Stringfellow’s] ‘Ariel’ is an ancestor of the great airliners ... [and today] the name ‘Ariel’ is once more important in the world of flying. The Ariel Hotel, the first circular hotel in Europe, stands beside London Airport.”. The hotel featured a print of the Aerial Steam Carriage over its mantel.[4]

See also

edit- Chard Museum

- Early flying machines

- History of aviation

- Timeline of aviation

- Timeline of aviation – 19th century

- John Chapman, engineer.[5]

- John Farey Jr., consultant engineer - recommended Richard Houchin of City Road, London to build a two-cylinder steam engine and boiler for the full-size Aerial Steam Carriage, Ariel.[6]

References

edit- ^ a b The Fort Worth Press, "Airplane Invention Was Delayed 60 Years", October 11, 1961

- ^ Chanute, Octave (1891). "Progress in Flying Machines". The American Engineer. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ^ HistoryNet.com, William Henson and John Stringfellow Archived October 30, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Modern Refrigeration", v. 64 – 1961

- ^ Penrose, Harald (1988). "3, Scheming a powered flyer; 4, Publicity Manoeuvring". An Ancient Air. Air Life Publishing Ltd. pp. 42–44, 49–50, 57–58.

- ^ Penrose, Harald (1988). "4, Publicity Manoeuvring". An Ancient Air. Air Life Publishing Ltd. p. 59.

Further reading

edit- Scientific American; September 23, 1848; Volume 4, Issue 1, page 4. "A series of experiments ...'

- New Scientist; "They All Laughed" October 11, 2003.

- Henson family documents in the archives of the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum.

External links

edit- Chard Museum has a large display of the work of John Stringfellow and William Henson.

- BBC: Aerial Steam Carriage

- Flying Machines: William Samuel Henson

- Stringfellow and Henson