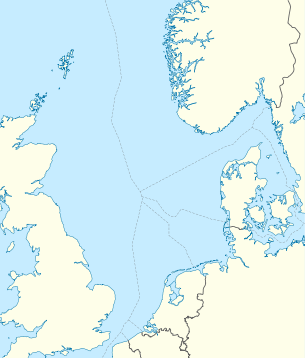

The action of 22 August 1795 was a minor naval engagement during the French Revolutionary Wars between a squadron of four British Royal Navy frigates and two frigates and a cutter from the Batavian Navy. The engagement was fought off the Norwegian coastal island of Eigerøya, then in Denmark-Norway, the opposing forces engaged in protecting their respective countries' trade routes to the Baltic Sea. War between Britain and the Batavian Republic began, undeclared, in the spring of 1795 after the Admiralty ordered British warships to intercept Batavian shipping following the conquest of the Dutch Republic by the French Republic in January 1795.

| Action of 22 August 1795 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars | |||||||

Defeat of the Dutch Fleet off Egerö, 22 August 1795, Nicholas Pocock, 1795 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 ship of the line 3 frigates |

2 frigates 1 cutter | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5 killed 18 wounded |

2 killed 15 wounded 1 frigate captured | ||||||

A British squadron of four frigates under the command of Captain James Alms was patrolling the entrance to the Skagerrak in August 1795 when three sails were spotted off the Norwegian coast to the north. Closing to investigate, the ships were discovered to be a Batavian squadron of two frigates and a small cutter. In the face of the larger British squadron the Batavian force turned away, sailing southeast along the Norwegian coast with the British approaching from the south in an effort to cut them off from the neutral Norwegian shore. At 16:15 the leading British ship HMS Stag caught and engaged the rearmost Batavian ship Alliantie (cdr. Claas Jager[2]); the remainder of the British squadron continued in pursuit of the Batavian squadron. For an hour Alliantie traded broadsides with the more powerful Stag and was eventually compelled to surrender. The remainder of the Batavian squadron escaped due to a fierce rearguard action by the frigate Argo, reaching the safety of the Dano-Norwegian harbour at Eigerøya.

Background

editIn the winter of 1794–1795 the armies of the French Republic overran the Dutch Republic, reforming the country into a sister republic named the Batavian Republic. The Dutch Republic was part of the Coalition against Republican France formed in the War of the First Coalition at the start of the French Revolutionary Wars, and their closest ally in Northern Europe was Great Britain.[3] In Britain the Admiralty was alarmed by developments in the Netherlands, particularly the seizure of the Dutch Navy by French cavalry units while the fleet was frozen into its winter harbour, and gave orders that the Royal Navy was to detain Dutch merchant and naval ships. As a result, the Batavian Republic and Great Britain began an undeclared war in the spring of 1795.[4]

In response to the threat that the Batavian fleet posed, the Admiralty established a new British fleet to oppose it. The Admiralty named this force, under the command of Admiral Adam Duncan, the North Sea Fleet. The fleet was based at Yarmouth in East Anglia and consisted mainly of older and weaker second-line vessels.[5] Duncan was also provided with a number of frigates, essential in securing the safe movement of the Baltic trade. Much of Britain's vital naval stores were obtained from Scandinavia and the trade routes through the Baltic Sea and North Sea were vital to the maintenance of the Royal Navy.[6] One Navy squadron that sailed from The Downs on 8 August 1795 with instructions to cruise off the mouth of the Skaggerak in the Eastern North Sea, consisted of four ships: 36-gun HMS Reunion under Captain James Alms, 32-gun HMS Stag under Captain Joseph Sydney Yorke, 50-gun HMS Isis under Captain Robert Watson and 28-gun HMS Vestal under Captain Charles White.[7]

The Scandinavian trade routes were equally important for the Batavian Navy, and to protect their merchant shipping from attack by British frigates, the Batavian authorities also sent a frigate squadron to the region, consisting of the 36-gun frigates Alliantie and Argo and the 16-gun cutter Vlugheid. On the afternoon of 22 August 1795 the Batavian force was sailing southeast along the Norwegian coast, then part of Denmark-Norway, tacking to port towards the land, when the British squadron was spotted approaching from the south.[6]

Battle

editWith their ships heavily outnumbered by the approaching British, the Batavian squadron made all sail along the coastline with the intention of sheltering in the neutral Dano-Norwegian harbour of Eigerøya.[8] Sighting the Batavian ships to the north, Alms ordered his squadron to give chase. Soon the fastest British ship, Stag made use of favourable wind to pull ahead of the others and at 16:15 succeeded in cutting off the rearmost Batavian vessel Alliantie from its companions. Although Alliantie with its 36-guns was a stronger ship than the 32-gun Stag, its main battery was of only 12-pounder cannon compared to Yorke's 18-pounder guns. This, coupled with the presence nearby of the rest of the British squadron meant that Alliantie, in the words of naval historian William James, "from the first, had no chance of success."[9]

Despite the odds against him, the Batavian captain engaged Stag, Yorke laying his ship alongside Alliantie and the frigates exchanging broadsides for an hour before the Batavian captain, his situation hopeless and his ship outnumbered and battered, surrendered at 17:15.[6] While Stag and Alliantie fought their duel, the action continued elsewhere, with the remaining Batavian ships making progress eastwards along the Norwegian coastline with the British squadron attempting to cut them off from the channel between Eigerøya and the Norwegian mainland in which the Batavian ships could shelter, protected by Dano-Norwegian neutrality.[6] Vlugheid rapidly outdistanced pursuit, but Argo was slower and came under heavy but distant fire from Reunion and Isis, replying in kind. Argo was subsequently found to have been hit thirty times by 24-pounder shot and had much of its sails and rigging torn away, requiring extensive repairs. Eventually the Batavian persistence paid off, and Vlugheid and Argo successfully escaped into the neutral harbour of Eigerøya before Alms could intercept them.[9]

Aftermath

editThe British suffered four killed and 13 wounded on Stag, one killed and three wounded on Reunion and two wounded on Isis. Only Vestal suffered no damage or casualties.[7] Total Batavian casualties in the engagement are unknown due to Alms' failure to record Alliantie's losses in his report to the Admiralty.[9] It is known that Argo lost two men killed and 15 wounded in the chase.[8] Alms sent Alliantie to England under Lieutenant Patrick Tonyn of Stag and ordered Lieutenant William Huggell of Reunion to deliver despatches to the Admiralty.[10] He remained at sea with his squadron, completing their assigned patrol. The surviving Batavian ships remained at anchor in the Eigerøya channel until the spring of 1796, when they successfully returned to Dutch ports.[11]

Alliantie was taken to Spithead and purchased by the Royal Navy, which renamed her HMS Alliance. Prize money was distributed to the crews of Alms' ships and shared equally among them; the crew of Isis alone shared £240 (the equivalent of £31,320 as of 2024).[12][13] The crew of Alliantie were sent to Ashford, Kent as prisoners of war.[14] Over the ensuing years, Duncan's fleet largely protected Britain's North Sea trade routes from Batavian attacks and in 1797 decisively defeated the Batavian navy at the Battle of Camperdown.[15] When news of the battle reached the Batavian Republic, there was widespread anger as they were not at war with Britain. On 3 September, the Provisional Representatives of the People of Holland issued a resolution ordering the Dutch envoy in Copenhagen, Christiaan Bangeman Huygens, to lodge a complaint over Alm's alleged violation of Dano-Norwegian neutrality. Huygens claimed in his complaint that Norwegian pilots had already gone onboard the Batavian ships prior to the battle, indicating that they had entered Dano-Norwegian waters; he also demanded that Denmark-Norway make representations at the Court of St James's to return Alliantie to the Batavian Republic.[16][17]

Admiral Jan Willem de Winter, the Batavian Navy's commander-in-chief, issued a proclamation after the battle praising the conduct of van Dirckinck's ships and censuring the British. The proclamation also noted that Argo suffered two killed and 15 injured during the battle and claimed that the Batavian brigs Echo, Gier and Mercuur stopped four British merchantmen and brought them into Kristiansand on 22 August in reprisal.[18] However, historian Gerrit Dirk Bom noted that de Winter was mistaken and that the brigs actually stopped the four merchantmen (along with one brig) on 19 August, which may have caused Alms to attack the Batavian squadron.[19] On 19 September, Huygens wrote to the Provisional Representatives, confirming that the Dano-Norwegian government had made diplomatic overtures to the British, which proved to be pointless, as Britain had already declared war on the Batavian Republic four days earlier.[20] In the letter, Huygens also noted that the crew of the four merchantmen were delivered to the British consul in Kristiansand, John Mitchell, on 22 August.[21]

Notes

edit- ^ Dirckinck, (Arnold Christiaan Leopold van), in: Abraham Jacob van der Aa, Karel Johan Reinier van Harderwijk, Gilles Dionysius Jacobus Schotel: Biographisch woordenboek der Nederlanden: bevattende levensbeschrijvingen van zoodanige personen, die zich op eenigerlei wijze in ons vaderland hebben vermaard gemaakt, Volume 4 (Van Brederode 1858), pp. 183-184

- ^ A.J. van der Aa, Biographisch woordenboek der Nederlanden, bevattende levensbeschrijvingen van zoodanige personen, die zich op eenigerlei wijze in ons vaderland hebben vermaard gemaakt, Volume 19 (Van Brederode 1878), p. 71

- ^ Chandler, p. 44

- ^ Woodman, p. 53

- ^ Gardiner, p. 170

- ^ a b c d Gardiner, p. 183

- ^ a b "No. 13809". The London Gazette. 29 August 1795. p. 896.

- ^ a b Clowes, p. 493

- ^ a b c James, p. 292

- ^ James, p. 293

- ^ Brenton, p. 93

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ "No. 14050". The London Gazette. 30 September 1797. p. 950.

- ^ Paul Chamberlain (2016). Hell Upon Water: Prisoners of War in Britain 1793-1815. History Press. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-7509-8053-1.

- ^ Gardiner, p. 176

- ^ Wagenaar, Jan (1803). Vaderlandsche historie, vervattende de geschiedenissen der Vereenigde Nederlanden, zints den aanvang der Noord-Americaansche onlusten, en den daar uit gevolgden oorlog tusschen Engeland en deezen staat, tot den tegenwoordigen tyd. Johannes Allaart. pp. 130–131.

- ^ Stuart, Martinus (1795). Nieuwe Nederlandsche Jaarboeken. Vol. 30. Amsterdam. p.5556

- ^ Stuart, op. cit., pp. 5774–5775

- ^ cf.Gerrit Dirk Bom "D'Vrijheid" 1781-1797: geschiedenis van een vlaggeschip (Bom 1897), p. 123

- ^ cf. Bom, op.cit., p. 124

- ^ Decreeten van de Provisioneele repræsentanten van het volk van Holland. 26 January 1795--2 Maart 1796, Volume 5, Part 1 ('Lands drukkerij, 1798), pp. 484-486

References

edit- Brenton, Edward Pelham (1837) [1825]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Vol. I. London: C. Rice.

- Chandler, David (1999) [1993]. Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars. Wordsworth Military Library. ISBN 1-84022-203-4.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (2001) [1996]. Fleet Battle and Blockade. Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-363-X.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume 1, 1793–1796. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-905-0.

- Woodman, Richard (2001). The Sea Warriors. Constable Publishers. ISBN 1-84119-183-3.