Acinocricus is a genus of extinct panarthropod belonging to the group Lobopodia and known from the middle Cambrian Spence Shale of Utah, United States. As a monotypic genus, it has one species Acinocricus stichus. The only lobopodian discovered from the Spence Shale, it was described by Simon Conway Morris and Richard A. Robison in 1988.[1] Owing to the original fragmentary fossils discovered since 1982, it was initially classified as an alga, but later realised to be an animal belonging to Cambrian fauna.[2]

| Acinocricus Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

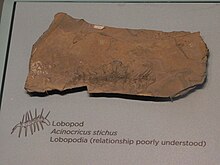

| Holotype specimen on display at the University of Kansas Natural History Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| (unranked): | Panarthropoda |

| Phylum: | †"Lobopodia" |

| Family: | †Luolishaniidae |

| Genus: | †Acinocricus Conway-Morris & Robison, 1988 |

| Species: | †A. stichus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Acinocricus stichus Conway-Morris & Robison, 1988

| |

Discovery

editThe first specimen of Acinocricus was discovered by American palaeontologist Lloyd Gunther in 1982 from the Spence Shale in Miners Hollow, Wellsville Mountains, Utah. It was embedded in hardened mud and was incomplete with some of its body part missing. More than a dozen fragmentary fossils were later recovered from the same site and the surrounding areas. Simon Conway Morris of the University of Cambridge and Richard A. Robison of the University of Kansas jointly published the systematic description and scientific name in 1988. The generic name is derived from two Greek words, akaina, meaning thorn or spine, and krikos, meaning ring or circle, for the circular spines on its body; the specific name stichos means row or line, referring to the arrangement of the spines.[1] Conway Morris and Robison made an erroneous classification by assigning it as an alga (in the phylum Chlorophyta) as they were convinced that it had no particular resemblance to any known animal fossils (medusoid) known at the time.[3]

The correct identification as an animal came only after a series of discoveries of Cambrian fossils (Maotianshan Shales) in Chengjian, China. A variety of lobopods were discovered in the early 1990s that showed important shared features with Acinocricus.[4][5][6] Comparison of the Chengjian lobopods and Acinocricus revealed their similarities.[3] In 1998, Jun-yuan Chen (Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences) and Lars Ramsköld (Uppsala University, Sweden) made assessment of all available Cambrian lobopod fossils and came to the conclusion that Acinocricus belongs to Lobopodia.[7]

Description

editAcinocricus is a soft-bodies worm-like animal having numerous stumpy legs called lobopods. It is most easily distinguished from spiral spines on its back.[2] It is for this appearance that it was originally believed as having body whorls that give a thallus-like structure and classified as an alga.[3] It is similar to other lobopods such as Luolishania longicruris,[8] Collinsovermis monstruosus,[9] Collinsium ciliosum in having several pairs of legs and spines on each body segment (somite).[10] It is for these reasons that it also classified under the family Luolishaniidae. Its major difference is that its spines are arranged in multiple rows on each somite, unlike in single pairs in other lobopods.[11][12] The spines are arranged in rows, and each row contains alternating large and small spines. The large spines measure up to 1.5. cm long, while the small spines are in at least two different sizes of less than 0.1 cm long.[1]

The exact number of the rows of spine and lobopods is difficult to make out due to fragmentary fossils. There are at least 12 pairs of lobopods, and the first five pairs are different from the rest in being longer and slender. The total length of the body can be up to 10 cm long. It is considered as lacking hardened body covering (sclerite). It is regarded as characteristically most closely related to Collinsovermis, with the major differences being its larger size, fewer anterior legs, absence of sclerites and its numerous rows of back spines.[13][14]

References

edit- ^ a b c Conway Morris, S.; Robison, Richard A. (1988). "More soft-bodied animals and algae from the Middle Cambrian of Utah and British Columbia". University of Kansas Paleontological Contributions. 122: 1–48. ISSN 0075-5052.

- ^ a b Kimmig, Julien; Strotz, Luke C.; Kimmig, Sara R.; Egenhoff, Sven O.; Lieberman, Bruce S. (2019). "The Spence Shale Lagerstätte: an important window into Cambrian biodiversity" (PDF). Journal of the Geological Society. 176 (4): 609–619. Bibcode:2019JGSoc.176..609K. doi:10.1144/jgs2018-195.

- ^ a b c LoDuca, S. T.; Bykova, N.; Wu, M.; Xiao, S.; Zhao, Y. (2017). "Seaweed morphology and ecology during the great animal diversification events of the early Paleozoic: A tale of two floras". Geobiology. 15 (4): 588–616. Bibcode:2017Gbio...15..588L. doi:10.1111/gbi.12244. PMID 28603844. S2CID 3864657.

- ^ Conway Morris, S. (1992). "Burgess Shale-type faunas in the context of the 'Cambrian explosion': a review". Journal of the Geological Society. 149 (4): 631–636. Bibcode:1992JGSoc.149..631C. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.149.4.0631. ISSN 0016-7649. S2CID 219540571.

- ^ Chen, Jun-yuan; Ramsköld, Lars; Zhou, Gui-qing (1994). "Evidence for Monophyly and Arthropod Affinity of Cambrian Giant Predators". Science. 264 (5163): 1304–1308. Bibcode:1994Sci...264.1304C. doi:10.1126/science.264.5163.1304. PMID 17780848. S2CID 1913482.

- ^ Ramsköld, L.; Xianguang, Hou (1991). "New early Cambrian animal and onychophoran affinities of enigmatic metazoans". Nature. 351 (6323): 225–228. Bibcode:1991Natur.351..225R. doi:10.1038/351225a0. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 4309565.

- ^ Ramsköld, L.; Chen, J–Y (1998). "Cambrian lobopodians, morphology and phylogeny". In Edgecombe, Gregory D. (ed.). Arthropod Fossils and Phylogeny. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 107–150. ISBN 978-0-231-09654-6.

- ^ Hou, Xian-Guang; Chen, Jun-Yuan (1989). "Luolishania gen. nov. : Un animal marin intermédiaire entre arthropode et annélidé du Cambrien inférieur de Chengjiang dans le Yunnan" [Luolishania gen. nov.: A marine animal intermediate between arthropod and annelid from the Lower Cambrian of Chengjiang in Yunnan]. Gǔshēngwùxué Bào (Acta Palaeontologica Sinica) (in French). 28 (2): 207–213.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Aria, Cédric (2020). "The Collins' monster, a spinous suspension-feeding lobopodian from the Cambrian Burgess Shale of British Columbia". Palaeontology. 63 (6): 979–994. doi:10.1111/pala.12499. S2CID 225593728.

- ^ Yang, Jie; Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Gerber, Sylvain; Butterfield, Nicholas J.; Hou, Jin-bo; Lan, Tian; Zhang, Xi-guang (2015). "A superarmored lobopodian from the Cambrian of China and early disparity in the evolution of Onychophora". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (28): 8678–8683. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112.8678Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1505596112. PMC 4507230. PMID 26124122.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Aria, Cédric (2017-01-31). "Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 29. Bibcode:2017BMCEE..17...29C. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5282736. PMID 28137244.

- ^ Liu, Jianni; Dunlop, Jason A. (2014). "Cambrian lobopodians: A review of recent progress in our understanding of their morphology and evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. Cambrian Bioradiation. 398: 4–15. Bibcode:2014PPP...398....4L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.06.008.

- ^ Kimmig, Julien; Strotz, Luke C.; Kimmig, Sara R.; Egenhoff, Sven O.; Lieberman, Bruce S. (2019). "The Spence Shale Lagerstätte: an important window into Cambrian biodiversity". Journal of the Geological Society. 176 (4): 609–619. Bibcode:2019JGSoc.176..609K. doi:10.1144/jgs2018-195. S2CID 134674792.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Aria, Cédric (2017). "Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 29. Bibcode:2017BMCEE..17...29C. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y. PMC 5282736. PMID 28137244.