This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (May 2024) |

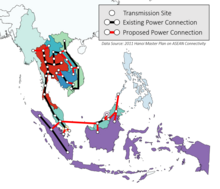

The ASEAN Power Grid (APG) is a key initiative under the ASEAN Vision 2020 and has the goal of achieving regional interconnection for energy security, accessibility, affordability and sustainability. The APG is a regional power interconnection initiative aiming to connect the electricity infrastructure of the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[1][2][3][4]

The main goal of the ASEAN Power Grid is to ensure energy security in the ASEAN region by integrating the power infrastructure across different countries. This includes the construction of cross-border power interconnections, which would allow the sharing of excess power capacity among ASEAN countries. The APG initiative is expected to enhance electricity trade across borders, meet the rising electricity demand, and improve access to energy services in the region. It is also seen as a way to promote the use of renewable energy sources within the region.[1][2][3][4][5]

History

editIn 1981, the first official discussions on the state of electricity grids within ASEAN began. This resulted in the creation of the "Heads of ASEAN Power Utilities/Authorities" group, otherwise known as HAPUA. However, it wasn't until 1996 that a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) was signed by members of ASEAN to give HAPUA 10 overarching goals, with one being power interconnectivity within each member state.[6]

The first discussions on inter-border energy trading took place during the Agreement on ASEAN Energy Cooperation in Manila, on June 24, 1986. This conference and the ensuing agreement highlighted the importance of cooperation among ASEAN members to develop energy resources and improve the economic integration of ASEAN collectively.[1][4]

During the Second ASEAN Informal Summit in Kuala Lumpur, on December 15, 1997, the "ASEAN Power Grid" was first mentioned in official documents as part of the "ASEAN Vision 2020" and within the "Hanoi Plan of Action". This event also marked the first time the organisation articulated the APG as the end goal for a unified energy market.[1][4]

A roadmap for the APG was first mentioned during the "17th ASEAN Ministers on Energy Meeting" (AMEM) in Bangkok on July 3, 1999. The meeting established the "ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation" (APAEC) for the years 2004–2009. A subsequent APAEC plan, covering 2004 to 2009, was adopted at the 22nd AMEM in Makati City on June 9, 2004. Both plans promoted the development of a policy framework that would guide legal and technical implementation methods. The ultimate goal of these plans was to establish an “Interconnection Master Plan” to help achieve the objectives outlined in the ASEAN Vision 2020.[1][4]

The legal aspect of this "Master Plan" was agreed as the "ASEAN Power Grid’s Roadmap for Integration" at the 20th AMEM Meeting in Bali on July 5, 2002. A final report entitled the "ASEAN Interconnection Master Plan Study (AIMS)" was approved by the 21st AMEM in Langkawi on July 3, 2003, to serve as the guiding document for the implementation of power interconnection projects.[1][4]

The full technical specifications of the project were initially agreed upon during the Tenth ASEAN Summit in Vientiane on November 29, 2004, and named the "Vientiane Action Programme (VAP) 2004-2010". The plan agreed upon a policy framework for power interconnection and trade, alongside the improvement of energy infrastructure in ASEAN. Again, there was a specific focus on interconnection projects between individual member states, as highlighted during the 2002 meeting.[1][4]

In 2007, the APGCC (ASEAN Power Grid Consultative Committee) was established under HAPUA and is an advice committee dedicated to creating and maintaining a framework to create the APG.[7]

In 2012, HAPUA was reorganised into 5 working groups, with one focused solely on inter-member transmission and the APG.[6]

In 2015, the 31st meeting of HAPUA took place, discussing the goal of achieving a 25% renewable energy mix by 2020 for the ASEAN power grid and reviewing funding proposals for the APG. The implementation of the Lao PDR – Thailand – Malaysia – Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP) was slated for 2018, with the expectation that insights gained would aid in addressing legal and tax harmonisation issues pertinent to establishing the ASEAN Electricity Regulator, APG Transmission System Operator (ATSO), and APG Generation & Transmission Planning (AGTP) institutions.[8]

Implementation

editThe implementation of the APG is expected to be carried out in stages, starting with bilateral agreements between neighbouring countries. These are then gradually to be expanded to sub-regional bases, eventually leading to a fully integrated power grid system in Southeast Asia.

As of now, several bilateral cross-border interconnections have been established, such as those between Thailand, Laos, Singapore, and Malaysia.[9]

The APGCC, the current technical committee leading development, has made a goal to create 16 interconnection projects with 27 physical links. Thirteen links are currently operating with a total capacity of 5.212 MW.[7]

Current system

edit| Year | Energy Production by Nation (EJ) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brunei | Cambodia | Indonesia | Lao PDR | Malaysia | Myanmar | Philippines | Singapore | Thailand | Vietnam | |

| 2020 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 10.0 | 0.2 | 3.8 | 1.0 | 2.6 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 3.8 |

| 2015 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 8.6 | 0.2 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 5.7 | 3.1 |

| 2010 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 8.5 | 0.1 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 4.9 | 2.5 |

| 2005 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 0.1 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 1.7 |

| 2000 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 0.1 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 | 3.0 | 1.2 |

The current combined ASEAN grid is quickly growing, with particular increases in generation within Indonesia and Vietnam.[10]

| Name | Converter

station 1 |

Converter

station 2 |

Additional stations | Total Length (Cable/Pole)

(km) |

Nominal

Voltage (kV) |

Power (MW) | Year | Type | Remarks | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peninsular Malaysia – Singapore | Plentong, Malaysia | Woodlands, Singapore | 230 | 450 | EE | [11][12][13] | ||||

| Peninsular Malaysia – Sumatra | Melaka | Pekan Baru | 600 | PP: SM->PM & EE | Under Construction | [11] | ||||

| Thailand - Peninsular Malaysia | Sadao, Thailand | Bukit Keteri, Malaysia | 132/115 | 80 | EE | [11][12][13] | ||||

| Thailand - Peninsular Malaysia | Su-ngai kolok | Rantau Panjang | 132/115 | 100 | EE | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Thailand - Malaysia | Khlong Ngae, Thailand | Gurun, Malaysia | 110

(0/110) |

300 | 300 | 2001 | Thyr | Supplier: Siemens | [11][13][14] | |

| Sarawak – West Kalimantan | Mambong, Malaysia | Bengkayang, Indonesia | 275 | 70 − 230 | EE | [11][12][13] | ||||

| Sarawak – Sabah – Brunei | Sarawak | Brunei | 275 | 2×100 | EE | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Nakhon Phanom, Thailand | Thakhek, Laos | Hinboun, Laos | 230 | 220 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | |||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Ubon Ratchathani 2, Thailand | Houay Ho, Laos | 230 | 126 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | ||||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Roi Et 2, Thailand | Nam Theun 2, Laos | 230 | 948 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | ||||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Udon Thani 3 | Na Bong | Nam Ngum 2 | 500 | 597 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | |||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Nakhon Phanom 2 | Thakhek | Theun Hinboun (Expansion) | 230 | 220 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | |||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Mae Moh 3 | Nan 2 | Hong Sa # 1, 2, 3 | 500 | 1473 | PP: La->Th | [11][12][13] | |||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Udon Thani 3 | Na Bong | Nam Ngiep 1 | 500 | 269 | PP: La->Th | Under Construction | [11] | ||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Ubon Ratchathani 3 | Pakse | Xe Pien Xe Namnoi | 500 | 390 | PP: La->Th | Under Construction | [11] | ||

| Thailand – Lao PDR | Khon Kaen 4 | Loei 2, Xayaburi | 500 | 1220 | PP: La->Th | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Lao PDR – Vietnam | Xekaman 3 | Thanhmy | 200 | PP: La->Vn | [11][12][13] | |||||

| Lao PDR – Vietnam | Xekaman 1 | Ban Hat San | Pleiku | 500 | 1000 | PP: La->Vn | Under Construction | [11] | ||

| Lao PDR – Vietnam | Nam Mo | Ban Ve | 230 | 100 | PP: La->Vn | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Lao PDR – Vietnam | Luang Prabang | Nho Quan | 500 | 1410 | PP: La->Vn | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Lao PDR – Cambodia | Ban Hat | Stung Treng | 230 | 300 | PP: La->Kh | Under Construction | [11] | |||

| Vietnam – Cambodia | Chau Doc | Takeo | Phnom Penh | 230 | 200 | PP: Vn->Kh | [11][12][13] | |||

| Thailand – Cambodia | Aranyaprathet | Bantey Meanchey | 115 | 100 | PP: Vn->Kh | [11][12][13] |

Brunei

editBrunei, along with Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines, has initiated a pilot project known as the Brunei Darussalam-Indonesia-Malaysia-Philippines Power Integration Project (BIMP-PIP). This project aims to study cross-border power trade among these countries.[15]

Indonesia

editIndonesia is set to launch the Nusantara Grid Project in 2025, which will connect the power networks among Indonesian islands, optimizing the use of renewable energy resources across the archipelago.[16]

Laos

editThe Lao PDR–Thailand–Malaysia–Singapore Power Integration Project serves as ASEAN's pilot in addressing technical, legal, and financial issues of multilateral electricity trade.[9]

Malaysia

editMalaysia is part of several cross-border power interconnections, including with Singapore and Thailand.[2] It has also agreed to purchase 100MW of electricity from Laos, utilizing the transmission grid of Thailand.[9]

Philippines

editThe Philippines, along with Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia, has initiated the BIMP-PIP to study cross-border power trade among these countries.[15]

Singapore

editSingapore has started importing renewable energy from Laos through Thailand and Malaysia as part of the Lao PDR–Thailand–Malaysia–Singapore Power Integration Project. The city-state is also planning to import up to 4 gigawatts of low-carbon electricity by 2035.[9]

Thailand

editIt is part of several cross-border power interconnections, including those with Malaysia, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam.[2]

Challenges and opportunities

editWhile the APG holds great potential for the ASEAN region, its implementation faces several challenges. These include the lack of a regional regulatory framework, differing national energy policies, and technical issues related to grid compatibility and synchronization.[citation needed]

Despite these challenges, the APG presents several opportunities. It could potentially lead to more efficient use of energy resources within the region, reduce the cost of electricity supply, and promote the use of renewable energy. Several leaders have highlighted the prospect of using renewable energy resources in countries such as Indonesia to make the APG green.[5][17] During the 31st HAPUA meeting, it was discussed that the ASEAN's power grid should be 25% green by 2020.[8]

Future expansions

editThe ASEAN Power Grid could be connected to the Asian Super Grid in the future, a proposed mega grid that stretches from India, to China, to Russia, and then to Japan.[18][19] It is currently unknown how the APG would connect to this plan.

There is a proposal by Australian company Sun Cable, called the Australia-Asia Power Link to connect the Singaporean and Australian power grids. Originally called the Australia–Singapore Power Link, then Australia-ASEAN, and finally to Australia-Asia, the idea is to physically connect the Northern Territory to Singapore, with a possible connection to Indonesia as well.[20] The Sun Cable company was placed in administration in early 2023 due to funding issues, but was bought by a consortium led by Grok Ventures and Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners in May 2023. The project aims to supply electricity to Darwin by 2030 and to Singapore a few years later.[21][22]

Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline Network

editThe Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGP) network is a key infrastructure project designed to enhance the distribution of natural gas across Southeast Asia, supporting regional energy security and economic integration. It is a part of ASEAN's broader efforts to improve energy cooperation and infrastructure within the region, complementing the ASEAN Power Grid, and sharing its goal of improved connected energy markets and electricity generation.[23][24][25][26][27]

The idea of the TAGP network was first outlined as part of the same 1997 meeting as the APG, and emphasized the need for greater energy cooperation among member states. The network aims to connect natural gas resources across ASEAN countries, ensuring a reliable, stable, and competitive energy supply, alongside new liberalisation in market controls and removal of bureaucratic 'red-tape'. The agency in charge of the project is the ASEAN Council on Petroleum (ASCOPE).[24][28]

The TAGP involves the development of pipelines linking key gas fields to major demand centers across Southeast Asia. Like the APG, the network spans several ASEAN nations, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and Myanmar. It is intended to improve the efficiency of natural gas transportation, reduce dependence on external energy sources, and promote energy diversification within the region.[24][29]

Implementation of the TAGP is planned in phases, beginning with bilateral and sub-regional pipeline links, with future expansion aimed at creating a fully integrated regional network.[25][29]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g "Memorandum of Understanding on the ASEAN Power Grid". asean.org. Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b c d "ASEAN Power Grid - Enhancing Electricity Interconnectedness" (PDF). 2015.

- ^ a b "ASEAN Power Grid". ASEAN Centre for Energy. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g "MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING ON THE ASEAN POWER GRID" (PDF). 2014.

- ^ a b "Clean Energy and Power Trade Development in Southeast Asia". ASEAN Centre for Energy. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b "History Of Hapua – Hapua". Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b "About APGCC – Hapua". Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b "31th MEETING OF THE HEADS OF ASEAN POWER UTILITIES/AUTHORITIES COUNCIL (HAPUA XXXI) MELAKA, MALAYSIA, MAY 22, 2015". 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-03-13.

- ^ a b c d "Building the ASEAN Power Grid: Opportunities and Challenges". SEADS. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b "Key findings – Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2022 – Analysis". IEA. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Ahmed a, Tofael; Mekhilef, Saad; Shah, Rakibuzzaman; Mithulananthan, N.; Seyedmahmoudian, Mehdi; Horan, Ben (January 2017). "ASEAN power grid: A secure transmission infrastructure for clean and sustainable energy for South-East Asia".

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Suryadi, Beni (4 June 2021). "Regional Power Grid Connectivity: The ASEAN Power Grid (APG)" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m ASEAN Center for Energy (16 Oct 2023). "Status of Southeast Asia Interconnectivity under ASEAN Power Grid" (PDF).

- ^ HVDC Projects List, March 2012 - Existing or Under Construction (PDF) Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Ece.uidaho.edu, accessed in February 2014

- ^ a b "Joint Statement of Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines Power Integration Project (BIMP-PIP)". asean.org. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ IBP, Journalist (2023-10-12). "Indonesia pledges participation in ASEAN Power Grid to establish integrated renewable electricity network | INSIDER". Indonesia Business Post. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "ASEAN AIPF Opened by President, PLN Presents Green Enabling Supergrid". www.jcnnewswire.com. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "An Asia Super Grid Would Be a Boon for Clean Energy—If It Gets Built". Council on Foreign Relations. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "A Green Super Grid for Asia—Renewable Energy Without Borders - AIIB Blog - AIIB". www.aiib.org. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "World's biggest clean energy project to power Singapore from Australia". New Atlas. 2021-09-28. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ Hannam, Peter (2023-09-07). "Sun Cable: Mike Cannon-Brookes takes charge of 'world-changing' solar project". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ Morton, Adam (2023-05-26). "Mike Cannon-Brookes wins control of Sun Cable solar project from Andrew Forrest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-05-25.

- ^ "Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipeline". ASEAN Centre for Energy. Retrieved 2024-12-20.

- ^ a b c Shi, Xunpeng; Variam, Hari Malamakkavu Padinjare; Shen, Yifan (2019-09-01). "Trans-ASEAN gas pipeline and ASEAN gas market integration: Insights from a scenario analysis". Energy Policy. 132: 83–95. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2019.05.025. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ^ a b "Pipe dreams: Turning an interconnected ASEAN gas market into a reality | Lowy Institute". www.lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 2024-12-20.

- ^ Syah, Rahmadha Akbar; Mahmud, Zaki Khudzaifi (2019-08-30). "Realism in the Trans ASEAN Gas Pipeline Project". Indonesian Journal of Energy. 2 (2): 89–98. doi:10.33116/ije.v2i2.39. ISSN 2549-760X.

- ^ Khadijah, Mutiara; Adolf, Huala; Setiawan, Setiawan (2022-06-22). "Regional Cooperation in The Utilization of Trans-ASEAN Gas Pipelines: An International Law Perspective". Substantive Justice International Journal of Law. 5 (1): 27–48. doi:10.56087/substantivejustice.v5i1.168. ISSN 2599-0462.

- ^ Instituto Argentino del Petróleo y del Gas. "THE TRANS-ASEAN GAS PIPELINE – ACCELERATING GAS MARKET INTEGRATION WITHIN THE ASEAN REGION" (PDF). www.iapg.org.ar.

- ^ a b ASCOPE (2019-06-10). "ASCOPE - TRANS ASEAN GAS PIPELINE PROJECT (TAGP)". www.ascope.org. Retrieved 2024-12-20.