5α-Reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs), also known as dihydrotestosterone (DHT) blockers, are a class of medications with antiandrogenic effects which are used primarily in the treatment of enlarged prostate and scalp hair loss. They are also sometimes used to treat excess hair growth in women and as a component of hormone therapy for transgender women.[1][2]

| 5α-Reductase inhibitor | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

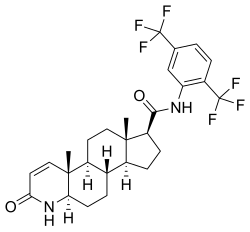

Dutasteride, one of the most widely used 5α-reductase inhibitors. | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Synonyms | Dihydrotestosterone blockers; DHT blockers |

| Use | Benign prostatic hyperplasia, pattern hair loss, hirsutism, feminizing HRT |

| ATC code | G04CB |

| Biological target | 5α-Reductase (1, 2, 3) |

| Chemical class | Steroids; Azasteroids |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

These agents inhibit the enzyme 5α-reductase, which is involved in the metabolic transformations of a variety of endogenous steroids. 5-ARIs are most known for preventing conversion of testosterone, the major androgen sex hormone, to the more potent androgen dihydrotestosterone (DHT), in certain androgen-associated disorders.

Medical uses

edit5-ARIs are clinically used in the treatment of conditions that are exacerbated by DHT:[3]

- Mild-to-moderate benign prostatic hyperplasia and lower urinary tract symptoms

- Pattern hair loss in both men and women

5-ARIs can be used in the treatment of hirsutism in women.[1] The usefulness of 5-ARIs for the potential treatment of acne is uncertain.[4] 5-ARIs are sometimes used as antiandrogens in feminizing hormone therapy for transgender women to help reduce body hair growth and scalp hair loss.[2]

They have also been explored in the treatment and prevention of prostate cancer. While the 5-ARI finasteride reduces the cancer risk by about a third, it also increases the fraction of aggressive forms of prostate cancer. Overall, there does not seem to be a survival benefit for prostate cancer patients under finasteride.[5]

Available forms

editFinasteride (brand names Proscar, Propecia) inhibits the function of two of the isoenzymes (types 2 and 3) of 5α-reductase.[6][7] It decreases circulating DHT levels by up to about 70%.[8] Dutasteride (brand name Avodart) inhibits all three 5α-reductase isoenzymes and can decrease DHT levels by 95%.[9][10] It can also reduce DHT levels in the prostate by 97 to 99% in men with prostate cancer.[11][12] Epristeride (brand names Aipuliete, Chuanliu) is marketed in China for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia.[13][14][15] However, it can only decrease circulating DHT levels by about 25 to 54%.[16] Alfatradiol (brand names Ell-Cranell Alpha, Pantostin) is a topical 5-ARI used to treat pattern hair loss in Europe.[17][18]

| Generic name | Brand name(s) | Isoforms | Route(s) | Launch |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfatradiol | Ell-Cranell Alpha, Pantostin | ? | Topical | ? |

| Dutasteride | Avodart | 1, 2, 3 | Oral | 2001 |

| Epristeride | Aipuliete, Chuanliu | 2, 3 | Oral | 2000 |

| Finasteride | Proscar, Propecia | 2, 3 | Oral | 1992 |

Side effects

edit5-ARIs are generally well tolerated in both men and women and produce few side effects.[19][20] However, they have been found to have some risks in studies with men, including slightly increased risks of decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, infertility, breast tenderness, gynecomastia, depression, anxiety, self-harm, and dementia.[20][21][22] In addition, although 5-ARIs decrease the overall risk of developing prostate cancer, they have been found to increase the risk of developing certain rare but high-grade forms of prostate cancer.[19] As a result, the FDA has notified healthcare professionals that the Warnings and Precautions section of the labels for the 5-ARI class of drugs has been revised to include new safety information about the increased risk of being diagnosed with these rare but more serious forms of prostate cancer.[23] Finasteride has also been associated with intraoperative floppy iris syndrome and cataract formation.[24][25] Depressive symptoms and suicidality have been reported.[26]

Sexual dysfunction

editSexual dysfunction, including erectile dysfunction, loss of libido, and reduced ejaculate, may occur in 3.4 to 15.8% of men treated with finasteride or dutasteride.[19][27] This is linked to lower quality of life and can cause stress in relationships.[28] There is also an association with lowered sexual desire.[29] It has been reported that in a subset of men, these adverse sexual side effects may persist even after discontinuation of finasteride or dutasteride.[29]

Breast changes

edit5-ARIs have a small risk of breast changes in men including breast tenderness and gynecomastia (breast development/enlargement).[20] The risk of gynecomastia is about 1.3%.[20] There is no association of 5-ARIs with male breast cancer.[20][30]

Emotional changes

editA 2017 population-based, matched-cohort study of 93,197 men aged 66 years and older with BPH found that finasteride and dutasteride were associated with a significantly increased risk of depression (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.73–2.16) and self-harm (HR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.34–2.64) during the first 18 months of treatment, but were not associated with an increased risk of suicide (HR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.53–1.45).[31][32][33][21] After the initial 18 months of therapy, the risk of self-harm was no longer heightened, whereas the elevation in risk of depression lessened but remained marginally increased (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.08–1.37).[31][32][21] The absolute increase in the rate of depression was 247 per 100,000 patient-years and of self-harm was 17 per 100,000 patient-years.[21][34] As such, on the basis of these findings, it has been stated that cases of depression in patients that are attributable to 5-ARIs will be encountered on occasion, while cases of self-harm attributable to 5-ARIs will be encountered very rarely.[34] There were no differences in the rates of depression, self-harm, and suicide between finasteride and dutasteride, suggesting that the specific 5-ARI used does not influence the risks.[33][21][34] The absolute risks of self-harm and depression with 5-ARIs remain low (0.14% and 2.0%, respectively).[35]

Pharmacology

editThe pharmacology of 5α-reductase inhibition is complex, but involves the binding of NADPH to the enzyme followed by the substrate. Specific substrates include testosterone, progesterone, androstenedione, epitestosterone, cortisol, aldosterone, and deoxycorticosterone. The entire physiologic effect of their reduction is unknown, but likely related to their excretion or is itself physiologic.[4] 5α-Reductase reduces the steroid Δ4,5 double bond in testosterone to its more active form DHT. Thus, inhibition results in decreased amounts of DHT. Because of this, slight elevations in testosterone and estradiol levels occur.[36] The 5α-reductase reaction is a rate-limiting step in the testosterone reduction and involves the binding of NADPH to the enzyme followed by the substrate.[4][37]

- Substrate + NADPH + H+ → 5α-substrate + NADP+

Beyond being a catalyst in the rate-limiting step in testosterone reduction, 5α-reductase isoforms I and II reduce progesterone to 5α-dihydroprogesterone (5α-DHP) and deoxycorticosterone to dihydrodeoxycorticosterone (DHDOC). In vitro and animal models suggest subsequent 3α-reduction of DHT, 5α-DHP and DHDOC lead to neurosteroid metabolites with effect on cerebral function. These neurosteroids, which include allopregnanolone, tetrahydrodeoxycorticosterone (THDOC), and 3α-androstanediol, act as potent positive allosteric modulators of GABAA receptors, and have antidepressant, anxiolytic, prosexual, and anticonvulsant effects.[38] 5α-Dihydrocortisol is present in the aqueous humor of the eye, is synthesized in the lens, and might help make the aqueous humor itself.[39] 5α-Dihydroaldosterone is a potent antinatriuretic agent, although different from aldosterone. Its formation in the kidney is enhanced by restriction of dietary salt, suggesting it may help retain sodium.[40] 5α-DHP is a major hormone in circulation of normal cycling and pregnant women.[41]

Other enzymes compensate to a degree for the absent conversion of 5α-reductase, specifically with local expression at the skin of reductive 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and oxidative 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzymes.[42]

In BPH, DHT acts as a potent cellular androgen and promotes prostate growth; therefore, DHT blockers inhibit and alleviate symptoms of BPH. In alopecia, male and female-pattern baldness is an effect of androgenic receptor activation, so reducing levels of DHT also reduces hair loss.

History

editFinasteride was the first 5-ARI to be introduced for medical use.[43] It was marketed for the treatment of BPH in 1992 and was subsequently approved for the treatment of pattern hair loss in 1997.[43] Epristeride was the second 5-ARI to be introduced and was marketed for the treatment of BPH in China in 2000.[14] Dutasteride was approved for the treatment of BPH in 2001 and was subsequently approved for pattern hair loss in South Korea in 2009 and in Japan in 2015.[44][45] The patent protection on finasteride and dutasteride has expired and both drugs are available as generic medications.[46][47]

Research

edit5-ARIs have been studied in combination with the nonsteroidal antiandrogen bicalutamide for the treatment of prostate cancer.[48][49][50][51][52][53][54]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Ulrike Blume-Peytavi; David A. Whiting; Ralph M. Trüeb (26 June 2008). Hair Growth and Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 368–370. ISBN 978-3-540-46911-7. Archived from the original on 9 November 2023. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ^ a b Wesp LM, Deutsch MB (2017). "Hormonal and Surgical Treatment Options for Transgender Women and Transfeminine Spectrum Persons". Psychiatr. Clin. North Am. 40 (1): 99–111. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.10.006. PMID 28159148.

- ^ Rossi S (Ed.) (2004). Australian Medicines Handbook 2004. Adelaide: Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 0-9578521-4-2

- ^ a b c Azzouni F, Godoy A, Li Y, Mohler J, et al. (2012). "The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: a review of basic biology and their role in human diseases". Adv. Urol. 2012: 530121. doi:10.1155/2012/530121. PMC 3253436. PMID 22235201.

- ^ Thompson, Ian M. Jr.; Goodman, Phyllis J.; Tangen, Catherine M.; Parnes, Howard L.; Minasian, Lori M.; Godley, Paul A.; Lucia, M. Scott; Ford, Leslie G. (2013-08-15). "Long-Term Survival of Participants in the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (7): 603–610. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1215932. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 4141537. PMID 23944298.

- ^ Yamana K, Labrie F, Luu-The V (January 2010). "Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride". Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2 (3): 293–9. doi:10.1515/hmbci.2010.035. PMID 25961201. S2CID 28841145.

- ^ Yamana K.; Labrie F.; Luu-The V.; et al. (2010). "Human type 3 5α- reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited finasteride and dutasteride". Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2 (3): 293–299. doi:10.1515/hmbci.2010.035. PMID 25961201. S2CID 28841145.

- ^ McConnell J. D.; Wilson J. D.; George F. W.; Geller J.; Pappas F.; Stoner E. (1992). "Finasteride, an inhibitor of 5α-reductase, suppresses prostatic dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 74 (3): 505–508. doi:10.1210/jcem.74.3.1371291. PMID 1371291.

- ^ Clark R. V.; Hermann D. J.; Cunningham G. R.; Wilson T. H.; Morrill B. B.; Hobbs S. (2004). "Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5α-reductase inhibitor". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (5): 2179–2184. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-030330. PMID 15126539.

- ^ Moss G. P. (1989). "Nomenclature of steroids (Recommendations 1989)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 61 (10): 1783–1822. doi:10.1351/pac198961101783. S2CID 97612891.

- ^ G. L. Andriole, P. Humphrey, P. Ray et al., "Effect of the dual 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride on markers of tumor regression in prostate cancer,"

- ^ Gleave M.; Qian J.; Andreou C.; et al. (2006). "The effects of the dual 5α-reductase inhibitor dutasteride on localized prostate cancer—results from a 4-month pre-radical prostatectomy study". The Prostate. 66 (15): 1674–1685. doi:10.1002/pros.20499. PMID 16927304. S2CID 40446842.

- ^ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 113–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9. Archived from the original on 24 February 2024. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ a b "Epristeride - AdisInsight". Archived from the original on 2016-11-08. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ "List of 21 Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Medications Compared". Archived from the original on 2017-12-11. Retrieved 2017-06-04.

- ^ Bentham Science Publishers (February 1996). Current Pharmaceutical Design. Bentham Science Publishers. pp. 70–.

- ^ Berger, Artur; Wachter, Helmut, eds. (1998). Hunnius Pharmazeutisches Wörterbuch (in German) (8th ed.). Walter de Gruyter Verlag. p. 486. ISBN 978-3-11-015793-2.

- ^ Mutschler, Ernst; Gerd Geisslinger; Heyo K. Kroemer; Monika Schäfer-Korting (2001). Arzneimittelwirkungen (in German) (8th ed.). Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 453. ISBN 978-3-8047-1763-3.

- ^ a b c Hirshburg JM, Kelsey PA, Therrien CA, Gavino AC, Reichenberg JS (2016). "Adverse Effects and Safety of 5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors (Finasteride, Dutasteride): A Systematic Review". J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 9 (7): 56–62. PMC 5023004. PMID 27672412.

- ^ a b c d e Trost L, Saitz TR, Hellstrom WJ (2013). "Side Effects of 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review". Sex Med Rev. 1 (1): 24–41. doi:10.1002/smrj.3. PMID 27784557.

- ^ a b c d e Welk B, McArthur E, Ordon M, Anderson KK, Hayward J, Dixon S (2017). "Association of Suicidality and Depression With 5α-Reductase Inhibitors". JAMA Intern Med. 177 (5): 683–691. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0089. PMC 5818776. PMID 28319231.

- ^ Welk, Blayne; McArthur, Eric; Ordon, Michael; Morrow, Sarah A.; Hayward, Jade; Dixon, Stephanie (2017). "The risk of dementia with the use of 5 alpha reductase inhibitors". Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 379: 109–111. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2017.05.064. ISSN 0022-510X. PMID 28716218. S2CID 4765640.

- ^ "FDA Alert: 5-alpha reductase inhibitors (5-ARIs): Label Change – Increased Risk of Prostate Cancer". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-06-08.

- ^ Wong, A. C. M.; Mak, S. T. (2011). "Finasteride-associated cataract and intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome". Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 37 (7): 1351–1354. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2011.04.013. PMID 21555201.

- ^ Issa, S. A.; Dagres, E. (2007). "Intraoperative floppy-iris syndrome and finasteride intake". Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery. 33 (12): 2142–2143. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.07.025. PMID 18053919.

- ^ Locci A, Pinna G (2017). "Neurosteroid biosynthesis downregulation and changes in GABAA receptor subunit composition: A biomarker axis in stress-induced cognitive and emotional impairment". Br. J. Pharmacol. 174 (19): 3226–3241. doi:10.1111/bph.13843. PMC 5595768. PMID 28456011.

- ^ Liu, L; Zhao, S; Li, F; Li, E; Kang, R; Luo, L; Luo, J; Wan, S; Zhao, Z (September 2016). "Effect of 5α-Reductase Inhibitors on Sexual Function: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 13 (9): 1297–310. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.006. PMID 27475241.

- ^ Gur, S; Kadowitz, PJ; Hellstrom, WJ (January 2013). "Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors on erectile function, sexual desire and ejaculation". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 12 (1): 81–90. doi:10.1517/14740338.2013.742885. PMID 23173718. S2CID 11624116.

- ^ a b Traish, AM; Hassani, J; Guay, AT; Zitzmann, M; Hansen, ML (March 2011). "Adverse side effects of 5α-reductase inhibitors therapy: persistent diminished libido and erectile dysfunction and depression in a subset of patients". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 8 (3): 872–84. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02157.x. PMID 21176115.

- ^ Wang J, Zhao S, Luo L, Li E, Li X, Zhao Z (2018). "5-alpha Reductase Inhibitors and risk of male breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Int Braz J Urol. 44 (5): 865–873. doi:10.1590/S1677-5538.IBJU.2017.0531. PMC 6237523. PMID 29697934.

- ^ a b Lee JY, Cho KS (May 2018). "Effects of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors: new insights on benefits and harms". Curr Opin Urol. 28 (3): 288–293. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000497. PMID 29528971. S2CID 4587434.

- ^ a b Traish, Abdulmaged M. (2018). "The Post-finasteride Syndrome: Clinical Manifestation of Drug-Induced Epigenetics Due to Endocrine Disruption". Current Sexual Health Reports. 10 (3): 88–103. doi:10.1007/s11930-018-0161-6. ISSN 1548-3584. S2CID 81560714.

- ^ a b Maksym RB, Kajdy A, Rabijewski M (January 2019). "Post-finasteride syndrome - does it really exist?". Aging Male. 22 (4): 250–259. doi:10.1080/13685538.2018.1548589. PMID 30651009. S2CID 58569946.

- ^ a b c Thielke S (2017). "The Risk of Suicidality and Depression From 5-α Reductase Inhibitors". JAMA Intern Med. 177 (5): 691–692. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0096. PMID 28319227.

- ^ Malde S, Cartwright R, Tikkinen KA (January 2018). "What's New in Epidemiology?". Eur Urol Focus. 4 (1): 11–13. doi:10.1016/j.euf.2018.02.003. PMID 29449167.

- ^ Andersson, S. (July 2001). "Steroidogenic enzymes in skin". European Journal of Dermatology. 11 (4): 293–295. ISSN 1167-1122. PMID 11399532.

- ^ Finn, Deborah A.; Beadles-Bohling, Amy S.; Beckley, Ethan H.; Ford, Matthew M.; Gililland, Katherine R.; Gorin-Meyer, Rebecca E.; Wiren, Kristine M. (2006). "A new look at the 5alpha-reductase inhibitor finasteride". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x. ISSN 1080-563X. PMC 6741762. PMID 16834758.

- ^ Finn, D. A.; Beadles-Bohling, A. S.; Beckley, E. H.; Ford, M. M.; Gililland, K. R.; Gorin-Meyer, R. E.; Wiren, K. M. (2006). "A New Look at the 5?-Reductase Inhibitor Finasteride". CNS Drug Reviews. 12 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1111/j.1527-3458.2006.00053.x. PMC 6741762. PMID 16834758.

- ^ Weinstein BI, Kandalaft N, Ritch R, Camras CB, Morris DJ, Latif SA, Vecsei P, Vittek J, Gordon GG, Southren AL (June 1991). "5 alpha-dihydrocortisol in human aqueous humor and metabolism of cortisol by human lenses in vitro". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 32 (7): 2130–5. PMID 2055703.

- ^ Kenyon CJ, Brem AS, McDermott MJ, Deconti GA, Latif SA, Morris DJ (May 1983). "Antinatriuretic and kaliuretic activities of the reduced derivatives of aldosterone". Endocrinology. 112 (5): 1852–6. doi:10.1210/endo-112-5-1852. PMID 6403339.

- ^ Milewich L, Gomez-Sanchez C, Crowley G, Porter JC, Madden JD, MacDonald PC (October 1977). "Progesterone and 5alpha-pregnane-3,20-dione in peripheral blood of normal young women: Daily measurements throughout the menstrual cycle". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 45 (4): 617–22. doi:10.1210/jcem-45-4-617. PMID 914969.

- ^ Andersson, S. (2001). "Steroidogenic enzymes in skin". European Journal of Dermatology. 11 (4): 293–295. PMID 11399532.

- ^ a b Alfred Burger; Donald J. Abraham (20 February 2003). Burger's Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery, Autocoids, Diagnostics, and Drugs from New Biology. Wiley. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-471-37030-7. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ William Llewellyn (2011). Anabolics. Molecular Nutrition Llc. pp. 968–, 971–. ISBN 978-0-9828280-1-4. Archived from the original on 2023-01-12. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- ^ MacDonald, Gareth (3 December 2015). "GSK Japan delays alopecia drug launch after Catalent manufacturing halt". Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ Robert T Sataloff; Anthony P Sclafani (30 November 2015). Sataloff's Comprehensive Textbook of Otolaryngology: Head & Neck Surgery: Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 400–. ISBN 978-93-5152-459-5. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ "Generic Avodart Availability". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2017-12-24.

- ^ Wang LG, Mencher SK, McCarron JP, Ferrari AC (2004). "The biological basis for the use of an anti-androgen and a 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor in the treatment of recurrent prostate cancer: Case report and review". Oncology Reports. 11 (6): 1325–9. doi:10.3892/or.11.6.1325. PMID 15138573.

- ^ Tay MH, Kaufman DS, Regan MM, Leibowitz SB, George DJ, Febbo PG, Manola J, Smith MR, Kaplan ID, Kantoff PW, Oh WK (2004). "Finasteride and bicalutamide as primary hormonal therapy in patients with advanced adenocarcinoma of the prostate". Annals of Oncology. 15 (6): 974–8. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdh221. PMID 15151957.

- ^ Merrick GS, Butler WM, Wallner KE, Galbreath RW, Allen ZA, Kurko B (2006). "Efficacy of neoadjuvant bicalutamide and dutasteride as a cytoreductive regimen before prostate brachytherapy". Urology. 68 (1): 116–20. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2006.01.061. PMID 16844453.

- ^ Sartor O, Gomella LG, Gagnier P, Melich K, Dann R (2009). "Dutasteride and bicalutamide in patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer: the Therapy Assessed by Rising PSA (TARP) study rationale and design". The Canadian Journal of Urology. 16 (5): 4806–12. PMID 19796455.

- ^ Chu FM, Sartor O, Gomella L, Rudo T, Somerville MC, Hereghty B, Manyak MJ (2015). "A randomised, double-blind study comparing the addition of bicalutamide with or without dutasteride to GnRH analogue therapy in men with non-metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer". European Journal of Cancer. 51 (12): 1555–69. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.04.028. PMID 26048455.

- ^ Gaudet M, Vigneault É, Foster W, Meyer F, Martin AG (2016). "Randomized non-inferiority trial of Bicalutamide and Dutasteride versus LHRH agonists for prostate volume reduction prior to I-125 permanent implant brachytherapy for prostate cancer". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 118 (1): 141–7. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2015.11.022. PMID 26702991.

- ^ Dijkstra S, Witjes WP, Roos EP, Vijverberg PL, Geboers AD, Bruins JL, Smits GA, Vergunst H, Mulders PF (2016). "The AVOCAT study: Bicalutamide monotherapy versus combined bicalutamide plus dutasteride therapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic carcinoma of the prostate-a long-term follow-up comparison and quality of life analysis". SpringerPlus. 5: 653. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2280-8. PMC 4870485. PMID 27330919.