A series of sit-in street protests, often called the Umbrella Revolution and sometimes used interchangeably with Umbrella Movement, or Occupy Movement, occurred in Hong Kong from 26 September to 15 December 2014.[12][13]

| Umbrella Revolution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of democratic development in Hong Kong and the Hong Kong–Mainland China conflict | |||||

The Admiralty protest site on the night of 10 October | |||||

| Date | 26 September 2014 – 15 December 2014 (2 months, 2 weeks and 5 days) | ||||

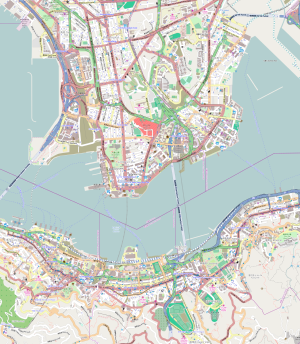

| Location | Hong Kong:

| ||||

| Caused by | Standing Committee of the National People's Congress decision on electoral reform regarding future Hong Kong Chief Executive and Legislative Council elections | ||||

| Goals |

| ||||

| Methods | Occupations, sit-ins, civil disobedience, mobile street protests, internet activism, hunger strikes, hacking | ||||

| Resulted in |

| ||||

| Concessions | The Hong Kong government promises to submit a "New Occupy report" to the Chinese Central government[6] | ||||

| Parties | |||||

| |||||

| Lead figures | |||||

| Injuries and arrests | |||||

| Injuries | 470+ (as of 29 Nov)[10] | ||||

| Arrested | 955[11] 75 turned themselves in | ||||

| |||||

The protests began after the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) issued a decision regarding proposed reforms to the Hong Kong electoral system. The decision was widely seen to be highly restrictive, and tantamount to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)'s pre-screening of the candidates for the Chief Executive of Hong Kong.[14]

Students led a strike against the NPCSC's decision beginning on 22 September 2014, and the Hong Kong Federation of Students and Scholarism started protesting outside the government headquarters on 26 September 2014.[15] On 28 September, events developed rapidly. The Occupy Central with Love and Peace movement announced the beginning of their civil disobedience campaign.[16] Students and other members of the public demonstrated outside government headquarters, and some began to occupy several major city intersections.[17] Protesters blocked both east–west arterial routes in northern Hong Kong Island near Admiralty. Police tactics – including the use of tear gas – and triad attacks on protesters led more citizens to join the protests and to occupy Causeway Bay and Mong Kok.[18][19][20] The number of protesters peaked at more than 100,000 at any given time, overwhelming the police thus causing containment errors.[21][22][23]

Government officials in Hong Kong and in Beijing denounced the occupation as "illegal" and a "violation of the rule of law", and Chinese state media and officials claimed repeatedly that the West had played an "instigating" role in the protests, and warned of "deaths and injuries and other grave consequences."[24] The protests precipitated a rift in Hong Kong society, and galvanised youth – a previously apolitical section of society – into political activism or heightened awareness of their civil rights and responsibilities. Not only were there fist fights at occupation sites and flame wars on social media, family members found themselves on different sides of the conflict.[25]

Key areas in Admiralty, Causeway Bay and Mong Kok were occupied and remained closed to traffic for 77 days. Despite numerous incidents of intimidation and violence by triads and thugs, particularly in Mong Kok, and several attempts at clearance by the police, suffragists held their ground for over two months. After the Mong Kok occupation site was cleared with some scuffles on 25 November, Admiralty and Causeway Bay were cleared with no opposition on 11 and 14 December, respectively.

The Hong Kong government's use of the police and courts to resolve political issues led to accusations that these institutions had been turned into political tools, thereby compromising the police and judicial system in the territory and eroding the rule of law in favour of "rule by law".[26][27][28][29] At times violent police action during the occupation was widely perceived to have damaged the reputation of what was once recognised as one of the most efficient, honest and impartial police forces in the Asia Pacific region.[30] The protests ended without any political concessions from the government, but instead triggered rhetoric from Chief Executive of Hong Kong Leung Chun-ying and mainland officials about rule of law and patriotism, and an assault on academic freedoms and civil liberties of activists.[27][31][32][33]

Background

editPolitical background

editAs a result of negotiations and the 1984 agreement between China and Britain, Hong Kong was returned to China and became its first Special Administrative Region on 1 July 1997, under the principle of "one country, two systems". Hong Kong has a different political system from mainland China. Hong Kong's independent judiciary functions under the common law framework.[34][35] The Hong Kong Basic Law, the constitutional document drafted by the Chinese side before the handover based on the terms enshrined in the Joint Declaration,[36] governs its political system, and stipulates that Hong Kong shall have a high degree of autonomy in all matters except foreign relations and military defence.[37] The declaration stipulates that the region maintain its capitalist economic system and guarantees the rights and freedoms of its people for at least 50 years after the 1997 handover. The guarantees over the territory's autonomy and the individual rights and freedoms are enshrined in the Hong Kong Basic Law, which outlines the system of governance of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, but which is subject to the interpretation of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC).[38][39]

The leader of Hong Kong, the Chief Executive, is currently elected by a 1200-member Election Committee, though Article 45 of the Basic Law states that "the ultimate aim is the selection of the Chief Executive by universal suffrage upon nomination by a broadly representative nominating committee in accordance with democratic procedures."[40] A 2007 decision by the Standing Committee opened the possibility of selecting the Chief Executive via universal suffrage in the 2017 Chief Executive election,[41] and the first round of consultations to implement the needed electoral reforms ran for five months in early 2014. Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying then, per procedure, submitted a report to the Standing Committee inviting them to deliberate whether it is necessary to amend the method of selection of the Chief Executive.[42]

As early as January 2013, legal scholar Benny Tai published an article by launching a non-violent civil disobedience of occupying Central if the government's proposal failed to satisfy the "international standards in relation to universal suffrage".[43] A group called the Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) was formed in March 2013 and held rounds of deliberations on the electoral reform proposals and strategies. In June 2014, the OCLP conducted a "civic referendum" on its own electoral reform proposal in which 792,808 residents, equivalent to over one fifth of the registered electorate, participated.[44]

In June 2014, the State Council issued a white paper called The Practice of the 'One Country, Two Systems' Policy in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region claiming "comprehensive jurisdiction" over the territory.[45] "The high degree of autonomy of the HKSAR [Hong Kong Special Administrative Region] is not full autonomy, nor a decentralised power," it said. "It is the power to run local affairs as authorised by the central leadership."[46]

Standing Committee decision on electoral reform

editOn 31 August 2014, the tenth session of the Standing Committee in the twelfth National People's Congress set limits for the 2016 Legislative Council election and 2017 Chief Executive election. While notionally allowing for universal suffrage, the decision imposes the standard that "the Chief Executive shall be a person who loves the country and loves Hong Kong," and stipulates "the method for selecting the Chief Executive by universal suffrage must provide corresponding institutional safeguards for this purpose". The decision states that for the 2017 Chief Executive election, a nominating committee, mirroring the present 1200-member Election Committee be formed to nominate two to three candidates, each of whom must receive the support of more than half of the members of the nominating committee. After popular election of one of the nominated candidates, the Chief Executive-elect "will have to be appointed by the Central People's Government." The process of forming the 2016 Legislative Council would be unchanged, but following the new process for the election of the Chief Executive, a new system to elect the Legislative Council via universal suffrage would be developed with the approval of Beijing.[17]

The Standing Committee decision is set to be the basis for electoral reform crafted by the Legislative Council. Hundreds of suffragists gathered on the night of the Beijing announcement near the government offices to protest the decision.[47][48]

In an opinion poll carried out by the Chinese University of Hong Kong between 8 and 15 October 2014, only 36.1% of 802 people surveyed accepted the NPCSC's decision. The acceptance rate rose to 55.6% on the proviso that the HKSAR Government would propose democratising the nominating committee after the planned second phase of public consultation.[49]

Events

editJuly 2014

editIn an atmosphere of growing discontent,[50] the annual 1 July protest march attracted the biggest numbers in a decade and ended in an overnight sit-in in Central with 5,000 police conducting over 500 arrests.[51][52]

September 2014

editInitial protests

editAt a gathering in Hong Kong on 1 September to explain the NPCSC decision of 31 August, deputy secretary general Li Fei said that the procedure would protect the broad stability of Hong Kong now and in the future.[47] Pro-democracy advocates said the decision was a betrayal of the principle of "one person, one vote," in that candidates deemed unsuitable by the Beijing authorities would be pre-emptively screened out by the mechanism, a point from which Li did not resile while maintaining that the process was "democratic".[47] About 100 suffragists attended the gathering, and some were ejected for heckling.[47] Police broke up a group of demonstrators protesting outside the hotel where Li was staying, arresting 19 people for illegal assembly.[53]

In response to the NPCSC decision, the Democratic Party legislators promised to veto the framework for both elections as being inherently undemocratic; Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) announced that it would organise civil disobedience protests and its three convenors led the Black Banner protest march on 14 September 2014 from Causeway Bay to Central.[47]

On 13 September 2014, representatives of Scholarism, including 17-year-old Agnes Chow Ting, staged a small protest against the NPCSC decision outside the Central Government Offices and announced a class boycott for university students for the week commencing 22 September. Alex Chow encouraged students unable to join in to wear a yellow ribbon to signify their support.[54] The Hong Kong Federation of Students (HKFS) (representing tertiary students) and Scholarism mobilised students for the class boycott, beginning with a rally attracting 13,000 students on the Chinese University of Hong Kong campus on the afternoon of 22 September.[55][56][57]

Scholarism organised a protest gathering by school students at the large Tamar Park, an integral part of the Government Headquarters complex, applying for permission from the responsible government department to occupy the part from 23 to 26 September. Permission was granted only for the first three days, the fourth day being reserved for a virtually unattended pro-Beijing rally.[58]: 17 Then having received a "notice of no objection" from the police to assemble for the 24 hours of 26 September 2014 on the relatively little-used Tim Mei Avenue, the students moved there in their hundreds, blocking traffic near the eastern entrance of the Central Government Offices.[59] At around 22:30, responding to calls from, first, Joshua Wong, the Convenor of Scholarism, and then Nathan Law, and led by Wong, up to 100 protesters went to "reclaim" Civic Square, a customarily open but recently closed public access area, by clambering over the perimeter fence.[58]: 19 [60] Wong was almost immediately arrested,[58]: 20 as police deployed pepper spray on those entering the square.[58]: 19 The police surrounded protesters at the centre and prepared to remove them overnight.[61][62] Protesters who chose to depart were allowed to do so; the rest were picked off and carried away one by one by groups of four or more police officers.

By the midnight of 26/27 September, 13 people had been arrested including Joshua Wong. Wong was held for 46 hours, released by police at 20:30 on 28 September[58]: 20 only upon his writ of habeas corpus being granted by the High Court.[63]

At 1:20 am (of 27 September), the police used pepper spray on a crowd that had gathered outside the Legislative Council, another part of the same complex, and some students were injured.

At 1:30 pm on 27 September, the police carried out the second round of clearances, and 48 men and 13 women were arrested for forcible entry into government premises and unlawful assembly[64] and one man was alleged to be carrying an offensive weapon. A police spokesman declared the assembly outside the Central Government Complex at Tim Mei Avenue illegal, and advised citizens to avoid the area. The arrested demonstrators, including Legislative Councillor Leung Kwok-hung and some HKFS members, were released around 9 pm. HKFS representatives Alex Chow and Lester Shum were, however, detained for 30 hours.[65] The police eventually cleared the assembly, arresting a total of 78 people.[66][67]

Occupy Central

editOccupy Central with Love and Peace had been expected to start their occupation on 1 October, but this was accelerated to capitalise on the mass student presence.[68] At 1:40 am on Sunday, 28 September, Benny Tai, one of the founders of OCLP, announced its commencement at a rally near the Central Government Complex.[68][69]

Later that morning, protests escalated as police blocked roads and bridges entering Tim Mei Avenue. Protest leaders urged citizens to come to Admiralty to encircle the police.[70] Tensions rose at the junction of Tim Mei Avenue and Harcourt Road after the police used pepper spray.

At around 4 pm on 28 September 2014, the footpaths of Harcourt Road could no longer contain the large numbers of demonstrators who were streaming to the location in support of those facing police pressure on Tim Mei Avenue. They spilled onto the busy artery in an irresistible surge. Traffic came to an abrupt halt. Occupy Central had begun.[71]

As night fell, armed riot police advanced from Wan Chai towards Admiralty and unfurled a banner that stated "WARNING, TEAR SMOKE". Seconds later, between 17:58 and 18:01, shots of tear gas were fired.[72][73][74] Then, the police gave them the above-mentioned message and a different message of "DISPERSE OR WE FIRE" concurrently.[75][76] At around 19:00,[77][non-primary source needed] the police was telling them to "move back (向後褪)" and pointed Remington Model 870 at them.[78] Around 6 hours later, Leung Chun-ying denied gunshot by the police.[79]

The heavy-handed policing, including the use of tear gas on peaceful protesters, inspired tens of thousands of citizens to join the protests in Admiralty that night.[20][21][80][81][82][83] Containment errors by the police – the closure of Tamar Park and Admiralty station – caused a spill-over to other parts of the city, including Wan Chai, Causeway Bay and Mong Kok.[21][84][85] 3,000 protesters occupied a road in Mong Kok and 1,000 went to Causeway Bay.[82] The total number of protesters on the streets swelled to 80,000,[85] at times considerably exceeding 100,000.[22][23]

The police confirmed that they fired tear gas 87 times.[86] At least 34 people were injured in that day's protests.[87] According to police spokesmen, officers exercised "maximum tolerance", and tear gas was used only after protesters refused to disperse and "violently charged".[88][89] The South China Morning Post (SCMP) reported, however, that police officers were seen charging the suffragists.[90] The media recalled that last time Hong Kong police used tear gas had been on Korean protesters during the 2005 World Trade Organization conference.[74][88]

On 29 September, the police adopted a less aggressive approach, sometimes employing negotiators to urge protesters to leave. 89 protesters were arrested; there were 41 casualties, including 12 police officers.[20] Chief Secretary for Administration, Carrie Lam announced that the second round of public consultations on political reform, originally planned to be completed by the end of the year, would be postponed.[91]

October 2014

editJoshua Wong and several Scholarism members attended the National Day flag raising ceremony on 1 October at the Golden Bauhinia Square, having undertaken not to shout slogans or make any gestures during the flag raising. Instead, the students faced away from the flag to show their discontent. Then District Councillor Paul Zimmerman opened a yellow umbrella in protest inside the reception after the ceremony.[92][93] Protesters set up a short-lived fourth occupation site at a section of Canton Road in Tsim Sha Tsui.[94]

By 2 October, activists had almost encircled the Central Government Headquarters.[21][95] Shortly before midnight, the Hong Kong Government responded to an ultimatum demanding universal suffrage with unscreened nominees: Carrie Lam agreed to hold talks with student leaders about political reform at a time to be fixed.[96]

On 3 October, violence erupted in Mong Kok and Causeway Bay when groups of anti-Occupy Central activists including triad members and locals attacked suffragists while tearing down their tents and barricades.[18][19][97][98] A student suffered head injuries. Journalists were also attacked.[18][99][100] The Foreign Correspondents' Club accused the police of appearing to arrest alleged attackers but releasing them shortly after.[101] One legislator accused the government of orchestrating triads to clear the protest sites.[19] It was also reported that triads, as proprietors of many businesses in Mong Kok, had their own motivations to attack the protesters.[83] There were 20 arrests, and 18 people injured, including 6 police officers. Eight of the people arrested had triad backgrounds, but were released on bail.[19][102] Student leaders blamed the government for the attacks, and halted plans to hold talks with the government.[103]

On 4 October, counter-protesters wearing blue ribbons marched in support of the police.[104] Patrick Ko of the Voice of Loving Hong Kong group accused the suffragists of having double standards, and said that if the police had enforced the law, protesters would have already been evicted.[105] The anti-Occupy group Caring Hong Kong Power staged their own rally, at which they announced their support for the use of fire-arms by police and the deployment of the People's Liberation Army.[106]

In the afternoon, Chief Executive CY Leung insisted that government operations and schools affected by the occupation must resume on Monday. Former Democratic Party lawmaker Cheung Man-Kwong claimed the occupy campaign was in a "very dangerous situation," and urged them to "sit down and talk, in order to avoid tragedy".[107] The Federation of Students demanded the government explain the previous night's events and said they would continue their occupation of streets.[108] Secretary for Security Lai Tung-kwok denied accusations against the police, and explained that tear gas had been used in Admiralty but not in Mong Kok because of the difference in geography. Police also claimed that protesters' barricades had prevented reinforcements from arriving on the scene.[109]

Democrat legislator James To said that "the government has used organised, orchestrated forces and even triad gangs in [an] attempt to disperse citizens."[19][110] Violent attacks on journalists were strongly condemned by The Foreign Correspondents' Club, the Hong Kong Journalists' Association and local broadcaster RTHK.[111] Three former US consuls general to Hong Kong wrote a letter to the Chief Executive asking him to solve the disputes peacefully.[112]

On 5 October, leading establishment figures sympathetic to the liberal cause, including university heads and politicians, urged the suffragists to leave the streets for their own safety.[113] The rumoured clearance operation by the police did not occur.[114] At lunchtime the government offered to hold talks if the protesters cleared the roads. Later that night, the government agreed to guarantee the protesters' safety, and HKFS leader Alex Chow announced that he had agreed to begin preparations for talks with Carrie Lam.[114]

On 9 October, the government cancelled the meeting with student leaders that had been scheduled for 10 October.[115] Carrie Lam explained at a news conference that "We cannot accept the linking of illegal activities to whether or not to talk."[116] Alex Chow said "I feel like the government is saying that if there are fewer people on the streets, they can cancel the meeting. Students urge people who took part in the civil disobedience to go out on the streets again to occupy."[116] Pan-democrat legislators threatened to veto non-essential funding applications, potentially disrupting government operations, in support of the suffragists.[117]

On 10 October, in defiance of police warnings, thousands of protesters, many with tents, returned to the streets.[117] Over a hundred tents were pitched across the eight-lane Harcourt Road thoroughfare in Admiralty, alongside dozens of food and first-aid marquees. The ranks of protesters continued to swell on the 11th.[118]

On 11 October, the student leaders issued an open letter to Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping saying that CY Leung's report to NPCSC on democratic development disregarded public opinion and ignored "Hong Kong people's genuine wishes."[119]

Clearance actions

editAt 5.30 am on 12 October, police started an operation to remove unmanned barricades in Harcourt Road (Admiralty site) to "reduce the chance of traffic accidents".[119] In a pre-recorded TV interview[120] CY Leung declared that his resignation "would not solve anything".[121] He said the decision to use tear gas was made by the police without any political interference.[122] Several press organisations including the Hong Kong Journalists Association objected to the exclusion of other journalists, and said that Leung was deliberately avoiding questions about the issues surrounding the electoral framework.[123][124]

On 13 October, hundreds of men, many wearing surgical masks and carrying crowbars and cutting tools, began removing barricades at various sites and attacking suffragists. Police made attempts to separate the groups. Suffragists repaired and reinforced some barricades using bamboo and concrete.[125][126][127] Protesters again claimed that the attacks were organised and involved triad groups.[128] Police made three arrests for assault and possession of weapons. Although police cautioned against reinforcing the existing obstacles or setting up new obstacles to enlarge the occupied area, suffragists later reinstated the barriers overnight.[125]

Anti-occupy protesters began to besiege the headquarters of Next Media, publisher of Apple Daily. They accused the paper of biased reporting.[129] Masked men among the protesters prevented the loading of copies of Apple Daily as well as The New York Times onto delivery vans.[130] Apple Daily sought a court injunction and a High Court judge issued a temporary order to prevent any blocking of the entrance.[131] Five press unions made a statement condemning the harassment of journalists by anti-occupy protesters.[132]

In the early morning of 14 October, police conducted a dawn raid to dismantle barricades in Yee Wo Street (Causeway Bay site), opening one lane to westbound traffic.[133] They also dismantled barricades at Queensway, Admiralty, and reopened it to traffic.[134]

Before midnight on 15 October, protesters stopped traffic on Lung Wo Road, the arterial road north of the Central Government Complex at Admiralty, and began erecting barricades. The police were unable to hold their cordon at Lung Wo Road Tunnel and had to retreat for reinforcements and to regroup. Around 3 am, police began to clear the road using batons and pepper spray. By dawn, traffic on the road resumed and the protesters retreated into Tamar Park, while 45 arrests were made.

Police assault Ken Tsang

editLocal television channel TVB broadcast footage of Civic Party member Ken Tsang being assaulted by police. He was carried off with his hands tied behind his back; then, while one officer kept watch, a group of about six officers punched, kicked and stamped on him for about four minutes.[135][136][137][138] Journalists complained that they too had been assaulted.[139][140] The video provoked outrage; Amnesty International joined others in calling for the officers to be prosecuted. In response, Secretary for Security Lai Tung-kwok said that "the officers involved will be temporarily removed from their current duties."[135][136] They were convicted and jailed in 2017 and Tsang commenced a claim for damages against the Commissioner of Police.[141]

At 5 am on 17 October, police cleared the barricades and tents at the Mong Kok site and opened the northbound side of Nathan Road to traffic for the first time in three weeks. In the early evening, at least 9000 protesters tried to retake the northbound lanes of the road. The police claimed that 15 officers sustained injuries. There were at least 26 arrests, including photojournalist Paula Bronstein.[142] Around midnight, the police retreated and the suffragists re-erected barricades across the road.[143][144]

On Sunday, 19 October, police used pepper spray and riot gear to contain the protesters in Mong Kok. Martin Lee, who was at the scene, said that "triad elements" had initiated scuffles with police "for reasons best known to themselves".[145] The police had arrested 37 protesters that weekend; the government said that nearly 70 people had been injured. At night, two pro-democracy lawmakers, Fernando Cheung and Claudia Mo, appeared at Mong Kok to mediate between the suffragists and the police, leading to a lowering of tensions as the police and suffragists each stepped back and widened the buffer zone. No clashes were reported for the night.[146]

On 20 October, a taxi drivers' union and the owner of CITIC Tower were granted a court injunction against the occupiers of sections of several roads.[147] In his first interview to international journalists since the start of the protests, CY Leung said that Hong Kong had been "lucky" that Beijing had not yet intervened in the protests, and repeated Chinese claims that "foreign forces" were involved.[148] He defended Beijing's stance on screening candidates. He said that open elections would result in pressure on candidates to create a welfare state, arguing that "If it's entirely a numbers game – numeric representation – then obviously you'd be talking to half the people in Hong Kong [that] earn less than US$1,800 a month [the median wage in HK]. You would end up with that kind of politics and policies."[149][150] A SCMP comment by columnist Alex Lo said of this interview: "Leung has set the gold standard on how not to do a media interview for generations of politicians to come."[151]

Televised debate

editOn 21 October, the government and the HKFS held the first round of talks in a televised open debate. HKFS secretary-general Alex Chow, vice secretary Lester Shum, general secretary Eason Chung, and standing members Nathan Law and Yvonne Leung met with Hong Kong Government representatives Chief secretary Carrie Lam, secretary of justice Rimsky Yuen, undersecretary Raymond Tam, office director Edward Yau and undersecretary Lau Kong-wah. The discussion was moderated by Leonard Cheng, the president of Lingnan University.[152][153][154][155] During the talks, government representatives suggested the possibility of writing a new report on the students' concerns to supplement the government's last report on political reform to Beijing, but stressed that civil nomination, as proposed by the students, fell outside the framework of the Basic Law and the NPCSC decision, which could be withdrawn.[156] The government described the talks as "candid and meaningful" in a press release, while the students expressed their disappointment at the lack of concrete results.[157]

On 22 October about 200 demonstrators marched to Government House, the official residence of the Chief Executive, in protest at his statement to journalists on 20 October about the need to deny political rights to the poor in Hong Kong.[158] At Mong Kok, members of the Taxi Drivers and Operators Association and a coalition of truck drivers attempted to enforce the court injunction granted two days earlier to remove barricades and clear the street. They were accompanied by their lawyer, who read out the court order to the demonstrators. Fist fights broke out during the afternoon and evening.[159]

also see vertical protest banners

On 23 October, a massive yellow vertical protest banner which read (in Chinese) "I want real universal suffrage" was hung on Lion Rock, the iconic hill that overlooks the Kowloon Peninsula and is seen to represent the spirit of Hong Kong.[160][161][162] The vertical protest banner was removed the following day.[163]

On 25 October, a group of anti-Occupy supporters wearing blue ribbons gathered at Tsim Sha Tsui to show their support of the police. Four journalists from RTHK and TVB tried to interview them and were attacked.[164] The police escorted the journalists away.[164] A female reporter for RTHK, a male reporter and two photographers for TVB were taken to hospital.[165] A group of about 10 men wearing facemasks attacked suffragists in Mong Kok.[166] Six people were arrested for common assault.[166] Alex Chow said that citizens deserved a chance to express their views over the constitutional reform proposal and the NPCSC's decision of 31 August. He said that the protest would only end if the government offered a detailed timeline or roadmap to allow universal suffrage and withdrawal of the standing committee decision.[167][168]

On 28 October, the HKFS issued an open letter to Chief Secretary Carrie Lam asking for a second round of talks. HKFS set out a prerequisite for the negotiation, that the government's report to the Chinese government must include a call for the retraction of the NPCSC's decision. The HKFS demanded direct talks with Chinese Premier Li Keqiang should the Hong Kong Government feel it could not fulfil this and other terms.[169] The 30th day since the police fired tear gas was marked at 5.57 pm exactly, with 87 seconds of silence, one for each tear gas canister that was fired.[170]

On 29 October, after James Tien of the pro-Beijing Liberal Party urged Leung to consider resigning in a public interview on 24 October,[171] the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference Standing Committee convened to discuss Tien's removal from the body as a move to whip the pro-establishment camp into supporting Leung and the country.[172] Tien, a long-time critic of Leung, said that Leung's position was no longer tenable as Hong Kong people no longer trusted his administration, and that his hanging onto office would only exacerbate the divisions in society.[173] Tien stepped down from his position as the leader of the Liberal Party after the removal.[174] Lester Shum refused bail extension based on conditions imposed after his arrest on 26 September, and was released unconditionally by police.[175] That day was also the day of the Umbrella Ultra Marathon event.

November 2014

editThe anti-Occupy group Alliance for Peace and Democracy had run a petition throughout the end of October to the start of November, and at the end of their campaign claimed to have collected over 1.8 million signatures demanding the return of streets occupied by the protesters and restoration of law and order. Each signator are required to show a valid Hong Kong ID card and the final result is checked and verified to make sure there is no multiple voting by the same individual. The group's previous signature collection has been criticised as "lack of credibility" by its opponents.[176][177]

The High Court extended injunctions on 10 November that had been granted to taxi, mini-bus and bus operators authorising the clearance of protest sites. On the following day, Carrie Lam told reporters that there would be no further dialogue with protesters. She warned that "the police will give full assistance, including making arrests where necessary" in the clearance of the sites, and advised the protesters to leave "voluntarily and peacefully".[178] However, the granting of the court order and the conditions attached to its execution attracted controversy as some lawyers and a top judge questioned why the order was granted based on an ex parte hearing, the urgency of the matter, and the use of the police when the order was for a civil complaint.[179]

On 10 November, around 1,000 pro-democracy demonstrators, many wearing yellow ribbons and carrying yellow umbrellas, marched to the PRC Liaison Office in Sai Wan to protest the arrests of people expressing support for the protest.[180] The marchers included Alex Chow, who announced that the Federation of Students were writing to the 35 local delegates to the National People's Congress to enlist their help in setting up talks with Beijing.[181] On 30 October Chow and other student leaders had announced that they were considering plans to take their protest to the APEC summit to be held in Beijing on 10 and 11 November.[182] As observers had predicted, the student delegation led by Chow was prevented from travelling to China when they attempted to leave on 15 November.[183] Airline officials informed them that mainland authorities had revoked their Home Return Permits, effectively banning them from boarding the flight to speak to government officials in Beijing.[184]

On 12 November, media tycoon Jimmy Lai was the target of an offal attack at the Admiralty site by three men, who were detained by volunteer marshalls for the protest site.[185][186] Both the attackers and the two site marshalls who restrained them were arrested by the police, which led to condemnation by the pan-democracy camp, who organised an unauthorised protest march the next day. The two marshalls from the protest site were later released on bail.[187]

On the morning of 18 November, in compliance with a court injunction, suffragists pre-emptively moved their tents and other affairs that were blocking access to Citic Tower, avoiding confrontation with bailiffs and the police over the removal of barricades.[188]

In the early hours of 19 November, protesters broke into a side-entrance to the Legislative Council Complex, breaking glass panels with concrete tiles and metal barricades. Legislator Fernando Cheung and other suffragists tried to stop the radical activists, but were pushed aside.[189][190] The break-in, which according to The Standard was instigated by Civic Passion,[191] was "strongly" condemned by Occupy Central for Love and Peace, and legislators from both the pan-democracy and pro-Beijing camps.[189]

On 21 November, up to 100 people gathered outside the British consulate accusing the former colonial power of failing to pressure China to grant free elections in the city and protect freedoms guaranteed in the Sino-British Joint Declaration.[192]

Amidst declining support for the occupation, bailiffs and police cleared the tents and barriers in the most volatile of the three Occupy sites, Mong Kok, on 25 and early 26 November. Suffragists poured into Mong Kok after the first day's clearance, and there was a stand-off between protesters and police the next day. Scuffles were reported, and pepper spray was used. Police detained 116 people during the clearance, including student leaders Joshua Wong and Lester Shum.[193] Joshua Wong, Lester Shum and some 30 of those arrested were bailed but subject to an exclusion zone centred around Mong Kok station.[194][195] Mong Kok remained the centre of focus for several days after the clearance of the occupied area, with members of the public angry about heavy-handed policing.[196][197] Fearing re-occupation, in excess of 4,000 police were deployed to the area.[196][197] Large crowds, ostensibly heeding a call from C. Y. Leung to return to the shops affected by the occupation, appeared nightly in and around Sai Yeung Choi Street South (close to the former occupied site); hundreds of armed riot police charged demonstrators with shields, pepper spraying and wrestling them to the ground. Protesters intent on "Gau Wu" (shopping) remained until dawn.[196][197]

Overnight on 30 November, there were violent clashes between police and protesters in Admiralty after the Federation of Students and Scholarism called upon the crowd to surround the Central Government Offices. The police used a hose to splash protesters for the first time. The entrance to the Admiralty Centre was also blocked. Most of the violence occurred near Admiralty MTR station.[198] Also, Joshua Wong and two other Scholarism members began an indefinite hunger strike.[199]

December 2014

editOn 3 December, the OCLP trio, along with 62 others, including lawmaker Wu Chi-wai and Cardinal Joseph Zen, turned themselves in to the police to bear the legal consequences of civil disobedience. However, they were set free without being arrested or charged.[200] They also urged occupiers to leave and transform the movement into a community campaign, citing concerns for their safety amidst the police's escalation of force in recent crackdowns.[201] Nonetheless, HKFS and Scholarism both continued the occupation. Nightly "Gau Wu" tours continued in Mong Kok for over a week after the clearance of the occupation site, tying up some 2500 police officers.[202] The minibus company that took out the Mong Kok injunction was in turn accused of having illegally occupied Tung Choi Street for years.[203]

On the morning of 11 December, many protesters left the Admiralty site before crews of the bus company that had applied for the Admiralty injunction dismantled roadblocks without resistance. Afterwards, the police set a deadline for protesters to leave the occupied areas and cordoned off the zone for the remainder of the day.[204] 209 protesters declined to leave and were arrested,[205][206][207] including several pan-democratic legislators and members of HKFS and Scholarism.[208] Meanwhile, the police set the bridge access to Citic Tower and Central Government Office only allowing media to access. The Independent Police Complaints Council was present to monitor the area for any "excessive use of force" along with fifty professors.[209]

On 15 December, police cleared protesters and their camps at Causeway Bay with essentially no resistance, bringing the protests to an end.[210][211]

Impact

editEffects on business and transport

editSurface traffic between Central and Admiralty, Causeway Bay, as well as in Mong Kok, was seriously affected by the blockades, with traffic jams stretching for miles on Hong Kong Island and across Victoria Harbour.[212][213] Major tailbacks were reported on Queensway, Gloucester Road and Connaught Road, which are feeder roads to the blockaded route in Admiralty.[68] With in excess of 100 bus or tram routes suspended or re-routed,[214] queues for underground trains in the Admiralty district spilled onto the street at times.[212] The MTR, the city's underground transport operator, was a beneficiary,[215] enjoying a 20 per cent increase in passenger trips recorded on two of its lines.[216] Others have opted to walk instead of driving.[217] Taxi drivers reported a fall in income as they had to advise passengers to use the MTR when faced with jams, diversions or blockaded roads.[218] Hong Kong Taxi Owners' Association claimed its members' incomes had declined by 30 per cent since the protests started.[219] Levels of PM2.5 particulate matter at the three sites declined to within the recommended safety levels of the World Health Organization.[220][221] An editorial in the South China Morning Post noted that, on 29 September, the air quality in all three of the occupied areas had markedly improved. The health risk posed by airborne pollutants was "low" – it was usually "high" – and there was a steep fall in the concentration of NO2. It said: "without a policy shift, after the demonstrations have ended, we will have to rely on our memories of the protest days for what clean vehicles on our roads mean for air quality".[222]

Nursery, primary and secondary schools within the Central and Western catchment areas were suspended from 29 September onwards. Classes for 25,000 primary students and 30,000 secondary students resumed on 7 October.[223][224][225] Kindergartens and nursery schools resumed operations on 9 October, adding to the traffic burden.[215] The Hong Kong Retail Management Association reported that chain stores takings declined between 30 and 45 per cent during the period 1–5 October in Admiralty, Central and Causeway Bay.[226] The media reported that some shops and banks in the protest areas were shuttered.[214]

According to the World Bank, the protests were damaging Hong Kong's economy while China remained largely unaffected.[212] Although the Hang Seng Index fell by 2.59% during the "Golden Week", it recovered and trading volume rose considerably.[227] Shanghai Daily published on 4 October estimated that the protests had cost Hong Kong HK$40 billion ($5.2 billion), with tourism and retail reportedly being hardest hit. However, tourist numbers for the "Golden Week" (beginning 1 October) were 4.83% higher than the previous year, according to the Hong Kong Tourism Board. While substantial losses by retailer were predicted, some stores reported a marked increase in sales.[227] Triad gangs, which had reportedly suffered a 40% decline in revenues, were implicated in the attacks in Mong Kok, where some of the worst violence had occurred.[102][117][228][229][230] Economic effects seemed either to be extremely localised or transient, and in any event much less than the dire predictions of business lobbies. One of the hardest hit may have been the Hong Kong Tramways Company, which reported a decline in revenues of US$1 million.[231][232] An economist said that the future stability will depend on political governance, namely if political issues such as income gaps and political reforms will be addressed.[229]

Effects on Hong Kong society

editThe protests have caused strong differences of opinion in Hong Kong society, with a "yellow (pro-occupy) vs. blue (anti-occupy)" war being fought, and unfriending on social media, such as Facebook.[25] Hong Kong people who oppose the Occupy protests do so for a number of different reasons. A significant part of the population, refugees from Communist China in the 1950s and 1960s, lived through the turmoil of the Hong Kong 1967 Leftist riots. Others feel that the protesters are too idealistic, and fear upsetting the PRC leadership and the possibility of another repeat of the crackdown that ended the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.[233] However, the overwhelming reason is the disruption to the lives of ordinary citizens caused by roads blocked, traffic jams, school closures, and financial loss to businesses (including in particular those run by the Triads in Mong Kok).[233] According to some reports, the police actions on the protesters has resulted in a breakdown of citizens' trust in the previously respected police force. The police deny accusations that they failed to act diligently.[81] The media have reported on individuals who have quit their jobs, or students abroad who have rushed home to become a part of history, and one protester saw this as "the best and last opportunity for Hong Kong people's voices to be heard, as Beijing's influence grows increasingly stronger".[83] Police officers have been working 18-hour shifts to the detriment of their family lives.[234] Front line police officers, in addition to working long hours, being attacked and abused on the streets, are under unprecedented stress at home. Psychologists working with police officers in the field report that some felt humiliated as they may have been unfriended on Facebook, and family may blame them for their perceived roles in suppressing the protests.[235][236][237] Although the media has often dubbed it "Asia's Finest", the reputation of the police has taken a serious drubbing following the heavy-handed treatment of protesters, as well as police brutality captured on camera and made viral.[30] Andy Tsang, the police commissioner appointed in 2011, is held responsible for the procedural escalation of police violence in the face of protesters, through deployment of riot police and 87 instances in which tear gas was released; dispersal of unarmed students also caused disquiet among senior police staffers.[30][238]

In an opinion poll of Hong Kong citizens carried out since 4 October by Hong Kong Polytechnic University, 59% of the 850 people surveyed supported the protesters in their refusal to accept the government plan for the 2017 election. 29% of those questioned, the largest proportion, blamed the violence that had occurred during the demonstrations on the chief Executive CY Leung.[234]

Triad involvement and counterprotester recruitment allegations

editThe BBC showed video footage from a Hong Kong TV network which appeared to show 'anti-Occupy protesters' being hired and transported to an Occupy protest site. The 'protesters', many of whom were initially unaware of what they were being paid to do, were secretly filmed on the bus being handed money by the organiser. Anonymous police sources informed the BBC Newsnight investigation that "back-up was strangely unforthcoming" to scenes of violence. The South China Morning Post also reported claims that people from poor districts were being offered up to HK$800 per day, via WhatsApp messaging, to participate in anti-Occupy riots.[81][239]

The Hong Kong police has stated that up to 200 gangsters from two major triads may have infiltrated the camps of Occupy Central supporters, although their exact motives are as yet unknown. A police officer explained the police could not arrest the triad gangsters there "if they do nothing more than singing songs for democracy".[240] A 2013 editorial in the Taipei Times of Taiwan described the pro-Beijing "grass-roots" organisations in Hong Kong: "Since Leung has been in office, three organizations – Voice of Loving Hong Kong, Caring Hong Kong Power and the Hong Kong Youth Care Association – have appeared on the scene and have been playing the role of Leung's hired "thugs", using Cultural Revolution-style language and methods to oppose Hong Kong's pan-democratic parties and groups."[241] Both Apple Daily and the Taiwan Central News Agency, as well as some pan-democrat legislators in Hong Kong, have named the Ministry of State Security and Ministry of Public Security as being responsible for the attacks.[242][243][244]

Legislative Council member James To alleged that "The police is happy to let the triad elements to threaten the students, at least for several hours, to see whether they would disperse or not." He added, "Someone, with political motive, is utilising the triad to clear the crowd, so as to help the government to advance their cause."[245] Amnesty International condemned the police for "[failing] in their duty to protect protesters from attacks" and stating that women were attacked, threatened, and sexually assaulted while police watched and did nothing.[81] Commander Paul Edmiston of the police admitted officers had been working long hours and had received heavy criticism. Responding to accusations that police chose not to protect the protesters, he said: "No matter what we do, we're criticized for doing too little or too much. We can't win."[88] An analysis in Harbour Times suggested that businesses that pay protection money to Triads in the neighbourhood stood to be affected by an occupation.[21] The journal criticised police response as being at first disorganised and slow onto the scene, but observed that its handling was within operating norms in triad-heavy neighbourhoods although it was affected by low levels of mutual trust, suspicion.[21]

Local media coverage

editMany of Hong Kong's media outlets are owned by local tycoons who have significant business ties in the mainland, so they all adopt self-censorship at some level and have mostly maintained a conservative editorial line in their coverage of the protests.[246] Next Media, being Hong Kong's only openly pro-democracy media conglomerate, has been the target of blockades by anti-Occupy protesters, cyberattacks, and hijacks of their delivery trucks. The uneven spread of viewpoints on traditional media has turned young people to social media for news, which The Guardian has described as making the protests "the best-documented social movement in history, with even its quieter moments generating a maelstrom of status updates, shares and likes."[247] People at protest sites now rely on alternative media whose launches were propelled by the protests, also called "umbrella revolution", or actively covered news from a perspective not found in traditional journals. Even the recently defunct House News resurrected itself, reformatted as The House News Bloggers. Radical viewpoints are catered for at Hong Kong Peanut, and Passion Times – run by Civic Passion.[246]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| seven plainclothes police officers beating up a handcuffed protester |

The prominent local station, TVB, originally broadcast footage of police officers beating a protester on 15 October, but the station experienced internal conflict during the broadcast.[248] The pre-dawn broadcasts soundtrack mentioning "punching and kicking" was re-recorded to say that the officers were "suspected of using excessive force".[249] Secret audio recordings from an internal meeting were uploaded onto YouTube that included the voice of TVB director Keith Yuen Chi-wai asking "On what grounds can we say officers dragged him to a dark corner, and punched and kicked him?"[249] The protester was later named as Civic Party member Ken Tsang, who was also a member of the Election Committee that returned CY Leung as the city's Chief Executive.[248] About 57 journalists expressed their dissatisfaction with the handling of the broadcast. A petition by TVB staff to management protesting the handling of the event was signed by news staff.[248] The list grew to 80+ people including employees from sports, economics and other departments.[250] In 2015, the video, entitled "Suspected Police Brutality Against Occupy Central Movement's Protester", was declared the Best TV news item at the 55th Monte Carlo TV Festival; it was praised for its "comprehensive, objective and professional" report. It also won a prize at the Edward E. Murrow Awards in the Hard News category.[251]

Internet security firm CloudFlare said that, like for the attacks on PopVote sponsored by OCLP earlier in the year, the volume of junk traffic aimed at paralysing Apple Daily servers was an unprecedented 500 Gbit/s and involved at least five botnets. Servers were bombarded with in excess of 250 million DNS requests per second, equivalent to the average volume of DNS requests for the entire Internet. And where the attacks do not succeed directly, they have caused some internet service providers to pre-emptively block such sites under attack to protect their own servers and lines.[252]

Chinese government and media

editBeijing is generally reported as being concerned about similar popular demands for political reform on the mainland that would erode the Communist Party's hold on power.[47] Reuters sources revealed that the decision to offer no concessions was made at a meeting of the National Security Commission of the Chinese Communist Party chaired by General secretary Xi Jinping in the first week of October. "[We] move back one step and the dam will burst," a source was reported as saying, referring to mainland provinces such as Xinjiang and Tibet making similar demands for democratic elections.[253][254] The New York Times China correspondents say that the strategy for dealing with the crisis in Hong Kong was being planned under supervision from the top-tier national leadership, which was being briefed on a daily basis. According to the report, Hong Kong officials are in meetings behind the scenes with mainland officials in neighbouring Shenzhen, at a resort owned by the central government liaison office.[255] Beijing's direct involvement was confirmed subsequently by pro-establishment figures in Hong Kong.[256] The HKFS, which had been hoping to send a delegation to meet with the leadership in Beijing, was rebuffed by Tung Chee-hwa, vice-chairman of the NPC, whom they asked to help set up the meetings.[257][258]

Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping stated his support for CY Leung on the 44th day of the occupation, saying the occupation was a "direct challenge not just to the SAR and its governance but also to Beijing". Xi also said that Leung's administration must govern to safeguard the rule of law and maintain social order.[259]

Censorship

editOn 28 September it emerged that Chinese government authorities had issued the following censorship directive: "All websites must immediately clear away information about Hong Kong students violently assaulting the government and about 'Occupy Central.' Promptly report any issues. Strictly manage interactive channels, and resolutely delete harmful information. This [directive] must be followed precisely."[260][261][262] Censors rapidly deleted messages internet posts with words such as "Hong Kong," "barricades", "Occupy Central" and "umbrella".[263][264] Sections of the CNN reporting from Hong Kong was also disrupted.[263] Most Chinese newspapers have not covered the protests except for editorials critical of the protests and devoid of any context,[263][265] or articles mentioning the negative impact of the occupation.[266] The Chinese website of the BBC was completely blocked after a video showing the violent assault on a protester by police on 15 October hosted on the site went viral.[267] Amnesty International reported that dozens of Chinese people have been arrested for showing support for the protests.[268] Facebook and Twitter are already blocked on the mainland, and now as a result of the sharing of images of the protests, PRC censors have now blocked Instagram.[264][269] However, Reuters noted that searches for "Umbrella Revolution" up to 30 September escaped censors on Sina Weibo but not on Tencent Weibo.[270] Despite this, certain American-funded reporting by the Voice of America and Radio Free Asia was able to break through some of the internet censors and provide information on the protests to inhabitants of the Chinese mainland.[271]

Allegations of foreign interference

editMainland Chinese officials and media have repeatedly alleged that outside forces fomented the protests. Li Fei, the first Chinese official to address Hong Kong about the NPCSC decision, accused democracy advocates of being tools for subversion by Western forces who were set at undermining the authority of the Communist Party. Li alleged that they were "sowing confusion" and "misleading society".[47] The People's Daily claimed that organisers of the Hong Kong protests learned their tactics from supporters of the Sunflower Student Movement in Taiwan, having first sought support from the United Kingdom and the United States.[272][273] Scholarism has been labelled as extremists and a pro-Beijing journal in Hong Kong alleged that Joshua Wong had been cultivated by "US forces".[274] In one of numerous editorials condemning the occupation, the People's Daily said "The US may enjoy the sweet taste of interfering in other countries' internal affairs, but on the issue of Hong Kong it stands little chance of overcoming the determination of the Chinese government to maintain stability and prosperity".[275] It alleged that the US National Endowment for Democracy was behind the protests, and that a director of the organisation had met with protest leaders.[276] On 15 October, an unnamed Chinese government official stated that "interference certainly exists", citing "the statements and the rhetoric and the behaviour of the outside forces of political figures, of some parliamentarians and individual media".[277]

In a televised interview on 19 October, Chief Executive CY Leung echoed Chinese claims about foreign responsibility for the protests, but declined to give details until an "appropriate time".[275][278] Six months later, on 22 April 2015, a reporter asked Leung, "has that time come yet?" Leung simply responded, "Well, I stand by what I say."[279] Three years later, Leung had yet to provide the promised substantiation.[280]

The US State Department has categorically rejected accusations of interference, calling the charges "an attempt to distract from...the people expressing their desire for universal suffrage."[281] The South China Morning Post characterised claims of foreign interference as "vastly exaggerated",[282] and longtime Hong Kong democracy advocate Martin Lee said such claims were a "'convenient excuse' for Beijing to cover its shame for not granting the territory true democracy as it once promised."[283]

The China Media Project of the University of Hong Kong noted that the phrase "hostile forces" (敌对势力) – a hardline Stalinist term – has been frequently used in a conspiracy theory alleging foreign sources of instigation.[284] Apart from being used as a straightforward means to avoid blame, analysts said that Chinese claims of foreign involvement, which may be rooted in Marxist ideology, or simply in an authoritarian belief that "spontaneity is impossible", are "a pre-emptive strike making it very difficult for the American and British governments" to support the protests.[24][285]

Law and order

editOn 1 October, China News Service criticised the protesters for "bringing shame to the rule of law in Hong Kong";[286] the People's Daily said that the Beijing stance on Hong Kong's elections is "unshakeable" and legally valid. Stating that the illegal occupation was hurting Hong Kong, it warned of "unimaginable consequences"[287] Some observers remarked that the editorial was similar to the April 26 Editorial that foreshadowed the suppression of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.[288][289] A state television editorial urged authorities to "deploy police enforcement decisively" and "restore the social order in Hong Kong as soon as possible," and again warned of "unimaginable consequences",[290] and a front page commentary in People's Daily on 3 October repeated that the protests "could lead to deaths and injuries and other grave consequences."[18][291]

By 6 October, official Chinese media outlets called for "all the people to create an anti-Occupy Central atmosphere in the society". The protesters were described as "going against the principle of democracy". A commentary in the China Review News claimed that "the US is now hesitant in its support for the Occupy Central. If those campaign organisers suddenly soften their approach, it will show that their American masters are giving out a different order."[292][293]

Chinese government officials have routinely affirmed the Chinese government's firm support for the chief Executive and for the continued "necessary, reasonable and lawful" actions by the police against the illegal protests.[148][277][286]

Other pronouncements

editWhile the Western press noticed the apparent silence of Hong Kong's richest businessmen since the occupation began,[294][295][296] Xinhua News Agency posted an English-language article in the morning of 25 October criticising the absence of condemnation of the occupation from the city's tycoons in response to the protest, but the article was deleted several hours later.[297][298] A replacement article that appeared that evening, in Chinese, stated how tycoons strongly condemned the protest, and quoted a number of them with pre-occupation soundbites reiterating how the occupation would damage Hong Kong's international reputation, disrupt social disorder and cause other harmful problems to society.[297]

Deputy director of China's National People's Congress Internal and Judicial Affairs Committee, Li Shenming, stated: "In today's China, engaging in an election system of one-man-one-vote is bound to quickly lead to turmoil, unrest and even a situation of civil war."[299] The mainland media also contested the protesters' demands for democracy by blaming the colonial rulers, saying Britain "gave our Hong Kong compatriots not one single day of it", notwithstanding the fact that de-classified British diplomatic documents indicate that the lack of democracy since at least late 1950s was largely attributable to the refusal of the PRC to allow it.[300]

The Chinese authorities are rumoured to have blacklisted 47 entertainers from Hong Kong who had openly supported the suffragists, and the list made the rounds on social media.[301] Denise Ho, Chapman To and actor Anthony Wong, who are among the highest profile supporters of the movement, were strongly criticised by the official Xinhua News Agency.[302] In response to the possible ban from the Chinese market, Chow Yun-fat, was quoted as saying "I'll just make less, then". Reporting of Chow's riposte was subject to Mainland Chinese internet censors.[303]

Beijing refused to grant a visa to Richard Graham, British member of parliament who had said in a parliamentary debate on Hong Kong that Britain had a duty to uphold the principles of the Sino-British joint declaration. This resulted in the cancellation of a visit by a cross-party parliament group due to visit China, led by Peter Mandelson. Graham had also asserted that "Stability for nations is not, in our eyes, about maintaining the status quo regardless, but about reaching out for greater involvement with the people – in this case, of Hong Kong – allowing them a greater say in choosing their leaders and, above all, trusting in the people".[304]

Chinese dissent

editIn urging students to set aside their protest, Bao Tong, the former political secretary of CCP general secretary Zhao Ziyang, said he could not predict what the leadership would do.[305] He believed Zhao meant universal suffrage where everyone had the right to vote freely, and not this "special election with Chinese characteristics".[305][306] Bao said today's PRC leaders should respect the principle that Hong Kong citizens rule themselves, or Deng Xiaoping's promises to Hong Kong would have been fake.[305][306] Hu Jia co-authored an opinion piece for the Wall Street Journal, in which he wrote "China has the potential to become an even more relentless, aggressive dictatorship than Russia... Only a strong, unambiguous warning from the US will cause either of those countries to carefully consider the costs of new violent acts of repression. Hong Kong and Ukraine are calling for the rebirth of American global leadership for freedom and democracy."[307]

Amnesty International said that at least 37 mainland Chinese have been detained for supporting Hong Kong protesters in different ways: some posted pictures and messages online, others had been planning to travel to Hong Kong to join protesters. A poetry reading planned for 2 October in Beijing's Songzhuang art colony to support Hong Kong protesters was disrupted, and a total of eight people were detained. A further 60 people have been taken in for questioning by police.[308][309] Amnesty reported in February 2015 that at least two of those arrested have been tortured, and nine denied legal representation; one was given access to a lawyer only after being sleep-deprived and tortured for five days. The whereabouts of four are unknown.[310]

Domestic reactions

editPolitical

editFormer Chief Secretary Anson Chan expressed disappointment at Britain's silence on the matter and urged Britain to assert its legal and moral responsibility towards Hong Kong and not just think about trade opportunities. Chan dismissed China's accusation of foreign interference, saying: "Nobody from outside could possibly stir up this sort of depth of anger and frustration."[311] Former Legco president Rita Fan said "to support the movement, some protesters background have resources that are supported by foreign forces using young people for a cause. To pursue democracy that effects other people's livelihood is a form of democratic dictatorship."[312]

Director of Hong Kong Human Rights Monitor, Law Yuk-kai, was dissatisfied with the unnecessary violence by the police. He said students only broke into the Civic Square to sit-in peacefully with no intentions of destroying government premises.[313] He questioned the mobilisation of riot police while protesters staged no conflict. Also, the overuse of batons was underestimated by the police because the weapon could severely harm protesters.[313] Contrary to the claims of other pro-establishment members, Tsang sees little evidence of "foreign forces" at play.[314] Member of Legislative Council Albert Ho of Democratic Party said, "[Attack on protesters] was one of the tactics used by the communists in mainland China from time to time. They use triads or pro-government mobs to try to attack you so the government will not have to assume responsibility."[315]

Former Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa when urging the students to end the occupation, praised their "great sacrifice" in the pursuit of democracy, and said that "the rule of law and obeying the law form the cornerstone of democracy."[316]

On 29 October, chairman of the Financial Services Development Council and Executive Councillor, Laura Cha, created controversy for the government and for HSBC, of which she is a board member, when she said: "African-American slaves were liberated in 1861, but did not get voting rights until 107 years later. So why can't Hong Kong wait for a while?" An online petition called for her to apologise and withdraw her remarks. A spokesman for the Executive Council stated in an e-mail on 31 October that "She did not mean any disrespect and regrets that her comment has caused concerns".[22][317][318][319]

Business sector

editThe Federation of Hong Kong Industries, whose 3,000 manufacturer members are largely unaffected as manufacturing in Hong Kong has been largely de-localised to the mainland, oppose the protests, due to concerns for the effects on investor confidence.[298] While the business groups have expressed concern at the disruption caused to their members,[320][321] the city's wealthiest individuals have kept a relatively low-profile as they faced the dilemma of losing the patronage of CCP leadership while trying to avoid further escalation with overt condemnations of the movement.[298] On the 19th day, Li Ka-Shing recognised that students' voices had been noted by Beijing, and urged them to go home "to avoid any regret".[322] Li was, however, criticised by Xinhua for not being unambiguous in his opposition for the movement and his support for Leung.[298] Lui Che Woo, one of the richest men in Asia, appeared to hold a more pro-Beijing stance by stating that "citizens should be thankful to the police".[323] Lui was opposed to "any activity that has a negative impact on the Hong Kong economy".[298]

International reactions

editUnited Nations

editOn 23 October, the UN Human Rights Committee, which monitors compliance with the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, urged China to allow free elections in Hong Kong.[324][325] The committee emphasised specifically that 'universal suffrage' includes the right to stand for office as well as the right to vote. Describing China's actions as "not satisfactory", the committee's chairman Konstantine Vardzelashvili announced that "The main concerns of Committee members were focused on the right to stand for elections without unreasonable restrictions."[326]

A spokesman for China's Foreign Ministry confirmed on the following day that the Covenant, signed by China in 1998, did apply to Hong Kong, but said that, nonetheless, "The covenant is not a measure for Hong Kong's political reform", and that China's policy on Hong Kong's elections had "unshakable legal status and effect". Reuters observed that "It was not immediately clear how, if the covenant applied to Hong Kong, it could have no bearing on its political reform."[327]

States

editMany countries, including Australia, Canada, France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Japan, Taiwan, Vatican City, United Kingdom, and the United States, supported the protesters' right to protest and their cause of universal suffrage and urged restraint on all sides, with the notable exception of Russia, whose state media claimed that the protests were another West-sponsored colour revolution similar to the Euromaidan.[24][328][329] German president Joachim Gauck, celebrating the 24th anniversary of German reunification, praised the spirit of Hong Kong's suffragists to their own of 24 years ago who overcame their fear of their oppressors;[330]

British Prime Minister David Cameron expressed deep concern about clashes in Hong Kong and said that he felt an obligation to the former colony.[331][332] Cameron said on 15 October that Britain should stand up for the rights set out in the Anglo-Chinese agreement.[333] The Foreign Office called on Hong Kong to uphold residents' rights to demonstrate, and said that the best way to guarantee these rights is through transition to universal suffrage.[334][335] Former Hong Kong Governor and current Chancellor of the University of Oxford Chris Patten expressed support for the protests[336] and denounced the Iranian-style democratic model for the city.[337] Citing China's obligation to Britain to adhere to the terms of Sino-British Joint Declaration,[338] he urged the British government to put greater pressure on the Chinese state, and to help China and Hong Kong find a solution to the impasse.[339] The Chinese Foreign Ministry said Patten should realise that "times have changed",[340] and that no party had the right to interfere in China's domestic affairs.[341]

British member of parliament and chairman of the Commons Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs, Richard Ottaway, denounced China's declaration that the committee would be refused permission to enter Hong Kong on their planned visit in late December as part of their inquiry into progress of the implementation of the Sino-British Joint Declaration. Ottaway sought confirmation from the China's deputy ambassador after receiving a letter from the central government that his group's visit "would be perceived to be siding with the protesters involved in Occupy Central and other illegal activities", and was told that the group would be turned back.[342]

In Taiwan, the situation in Hong Kong is closely monitored since China aims to reunify the island with a "one country, two systems" model similar to one that is used in Hong Kong.[343] President Ma Ying-jeou expressed concern for the developments in Hong Kong and its future,[344] and said the realisation of universal suffrage will be a win-win scenario for both Hong Kong and mainland China.[345] On 10 October, Taiwan's National Day, President Ma urged China to introduce constitutional democracy, saying "now that the 1.3 billion people on the mainland have become moderately wealthy, they will of course wish to enjoy greater democracy and rule of law. Such a desire has never been a monopoly of the west, but is the right of all humankind."[346] In response to Ma's comments, China's Taiwan Affairs Office said Beijing was "firmly opposed to remarks on China's political system and Hong Kong's political reforms .... Taiwan should refrain from commenting on the issue."[347]

Foreign media

editThe protests captured the attention of the world and gained extensive global media coverage.[348] Student leader Joshua Wong featured on the cover of Time magazine during the week of his 18th birthday,[349] and the movement was written about, also as a cover story, the following week.[350] While the local pan-democrats and the majority of the Western press supported the protesters' aspirations for universal suffrage,[348] Martin Jacques, writing for The Guardian, argued that the PRC had "overwhelmingly honoured its commitment to the principle of one country, two systems". He believed that the reason for the unrest is "the growing sense of dislocation among a section of Hong Kong's population" since 1997.[351] Tim Summers, in an op-ed for CNN, said that the protests were fuelled by dissatisfaction with the Hong Kong government, but the catalyst was the decision of the NPCSC. Criticising politicians' and the media's interpretation of the agreements and undertakings of the PRC, Summers said "all the Joint Declaration said is that the chief executive will be 'appointed by the central people's government on the basis of the results of elections or consultations to be held locally [in Hong Kong].' Britain's role as co-signatory of that agreement gives it no legal basis for complaint on this particular point, and the lack of democracy for the executive branch before 1997 leaves it little moral high ground either."[352]

Aftermath

editOnce traffic resumed, roadside PM2.5 readings rose back up to levels in excess of WHO recommended safe levels of 25 μg/m³. According to the Clean Air Network, PM2.5 levels at Admiralty stood at 33 μg/m³, an increase of 83% since during the occupation; Causeway Bay measured 31 μg/m³, an increase of 55%, and Mong Kok's reading of 37 μg/m3 represents an increase of 42%.[220][221] The former director of the government archives, Simon Chu, expressed concern about preservation of official documents pertaining to the protest movement, and was seeking a proxy to file an injunction on the government. He feared that the absence of a law on official archives in Hong Kong meant that senior government officials may seek to destroy all documents involving deliberations, decisions and actions taken while the protests were ongoing.[353]

Chief Executive CY Leung said that protesters need to carefully consider what sort of democracy they are pursuing.[354] He welcomed the end of the occupation, saying: "Other than economic losses, I believe the greatest loss Hong Kong society has suffered is the damage to the rule of law by a small group of people... If we just talk about democracy without talking about the rule of law, it's not real democracy but a state of no government".[355] Leung saw his popularity ratings slump to a new low following the occupation protests, down to 39.7 per cent, with a net of minus 37%. This was attributed to public perception of Leung's unwillingness to heal the wounds, and his unwarranted[according to whom?] shifting of the blame for the wrongs in society onto opponents. Leung also claimed negative effects on the economy without providing evidence, and his assertions were contradicted by official figures.[356] On 19 December 2014, the eve of the 15th anniversary of Macau's handover, authorities in Macau banned journalists covering the arrival of Chinese leader Xi Jinping from holding umbrellas in the rain.[357]

Commissioner of the Police Andy Tsang confirmed the unprecedented challenges to the police posed by the occupations, and that as at 15 December a total of 955 individuals had been arrested,[354][358] 221 activists had been hurt, and that 130 police officers had received light injuries.[358] At the same time, Tsang anticipated further arrests, pending a three-month investigation into the occupation movement.[358] Most activists call in under arrest by appointment remain to be formally charged, and although police said that they reserved the right to prosecute, pro-democracy legislators complained that the uncertain impending prosecution hangs over the interviewees constituted an act of intimidation.[359]

Although the occupations had ended, aggressive policing that became a hallmark of the official antipathy towards peaceful protests continued – as illustrated by police application for Care and Protection Orders (CPO) for two young suffragists in December 2014.[360] Typically, CPOs are only used in severe cases of juvenile delinquency, and could lead to the minor being sent to a children's home and removed from parental custody.[360] Police arrested one 14-year-old male for contempt of court during the clearance of Mong Kok and applied for a CPO.[360][361] The CPO was cancelled four weeks later when the Department of Justice decided that they would not prosecute.[360]

In a second case, a 14-year-old female who drew a chalk flower onto the Lennon Wall on 23 December 2014 was arrested on suspicion of criminal damage, detained by police for 17 hours, and then held against her will in a children's home for 20 days, but was never charged with any crime.[362] A magistrate decided in favour of a CPO pursuant to a police application, deeming it "safer." The incident created uproar as she was taken away from her hearing-impaired father, and was unable to go to school.[363][364][365] On 19 January, another magistrate rescinded the protection order[366] for the girl–now commonly known as "Chalk Girl" (粉筆少女)–however overall handling of the situation by police and government officials raised broad concerns. There is no official explanation as to why proper procedures were not followed or as to why, in accordance with regulations, social workers were never consulted before applying for the order.[367] The controversy gained international attention, and The Guardian produced a short documentary film about her story, titled "The Infamous Chalk Girl" which was released in 2017.[368][369] Usage of the protection orders against minors involved in the Umbrella Movement was seen as "white terror" to deter young people from protesting.[360]

Post mortems